Works in Conversation

UT’s Blanton Museum of Art turns 50 this spring with a new exhibit of masterpieces owned by Longhorns.

UT’s Blanton Museum of Art turns 50 this spring with a new exhibit of masterpieces owned by Longhorns.

Join us for a guided tour of Through the Eyes of Texas: Masterworks from UT Collections.

When staff at UT’s Blanton Museum of Art decided to mark the museum’s 50th birthday with an exhibit of art owned by alumni, they suspected that at least a few Longhorns’ private collections had world-class pieces. But what they found blew them away.

“Almost immediately we found three Monet waterlilies, all owned by different alumni,” says curator Annette DiMeo Carlozzi. “I knew then it was going to be big. Monet waterlilies are what you think of when you think of a masterwork.”

After a year of planning, including more than 150 home visits, Carlozzi and other Blanton staff winnowed more than 3,000 pieces of art to a final 200. Those gems make up Through the Eyes of Texas: Masterworks from UT Collections, on display Feb. 24 to May 19.

Most exhibits adhere to a central organizing theme, such as an era, style, or artist. Through the Eyes of Texas has excellence as its only criterion. From an ancient Chinese urn to contemporary photography, the exhibit spans centuries and continents. But that doesn’t mean it’s not cohesive. “I’ve put the works in conversation with one another,” Carlozzi says. “That allows visitors to see how subjects are treated over time and by very different artists.” One series explores the idea of female beauty; another features typography.

The Blanton is also using the exhibit as a teaching tool for art students. “Ninety percent of these works have not been seen in public before,” Carlozzi says. “We’re excited.”

Your Guides

Don Bacigalupi

MA ’85, PhD ’93

Director, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Collette Crossman

Curator of exhibitions,

Blanton Museum of Art

Annette DiMeo Carlozzi

Curator-at-large,

Blanton Museum of Art

Alumni Collectors

Julius Glickman

BA ’62, LLB ’66, Life Member,

Distinguished Alumnus, and

Suzan Glickman

BS ’64, Life Member

Lucy Crow Billingsley

BBA ’75, Life Member

Tom Dunning

BBA ’65, Life Member, and Sally Dunning

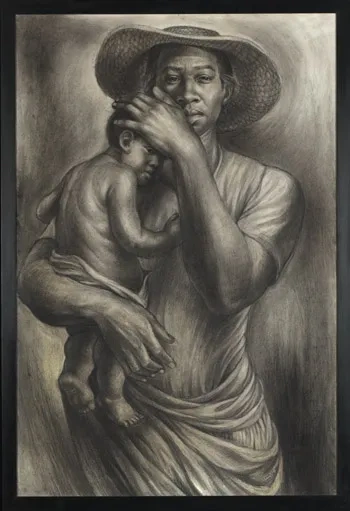

Charles White: Ye Shall Inherit the Earth, 1953

Charcoal on paper, 36 x 26 in., Princeton University Art Museum, On loan from a private collection, Princeton, NJ

Don Bacigalupi: This piece encapsulates so many things: religious associations, the Harlem Renaissance, the burgeoning civil rights movement.

Annette Carlozzi: I love the contrast between the humility of the subjects and the majestic quality of the mother and child. It’s a symbol for parenting, for survival, and it really moves me.

Bacigalupi: For a work of art to be great, it has to appeal on three levels—visually, intellectually, emotionally—and this one is firing on all cylinders.

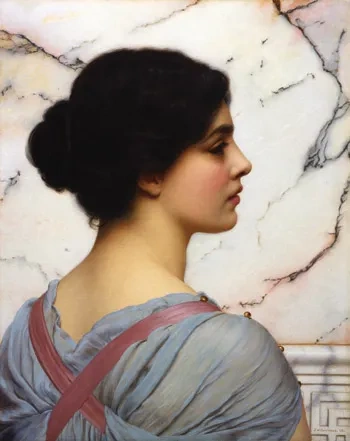

John William Godward: Bellezza Pompeiana, 1909

Oil on canvas, 20 x 16 in., Collection of Julius Glickman, BA ’62, LLB ’66, Life Member,

Distinguished Alumnus, and Suzan Glickman, BS ’64, Life Member

Carlozzi: This is a British painting from the Victorian period. The artist is very interested in Greek and Roman times, so her clothing is representative of that era. She’s also a very classic beauty.

Julius Glickman: As a collector, there are a lot of things I’m thinking about when considering buying a piece. Many paintings are striking, but will we grow weary of them over time? Does it represent the best of the artist’s work? Is it a good investment financially? Often we’ll go back several times to look before buying.

With the Godward, there are so many things to look at. The marble background, her dress—it’s just very striking. It says a lot about history, because the Brits were at the height of their empire when it was painted—and that’s when they were obsessed with the Greek and Roman empires, too.

Unknown (Roman): Head of a Goddess, 2nd century A.D.

Marble, 15 1/2 in. tall, San Antonio Museum of Art, bequest of Gilbert M. Denman Jr., BA ’40, LLB ’42

Bacigalupi: Much of our understanding of ancient art is a misunderstanding. Today almost all ancient statues are monochromatic—in white marble or bronze—but many had vibrant color when they were created. This statue may have been at a temple or a shrine. It may have been very colorful, maybe adorned with gold or ivory or other materials. Today we can hardly imagine how it looked to the artist who made it.

Carlozzi: The ravages of time have changed its appearance. Time and history become something you can actually see.

Thomas Struth: Paradise 24, Sao Francisco de Xavier, Brazil, 2001

Chromogenic print, 82 7/8 x 106 in., Edition 6/10, Collection of Sally and Tom Dunning, BBA ’65, Life Member

Bacigalupi: [In person], it’s bigger than any photograph you’ve ever seen outside of a billboard. Struth was responding to painters like Pollock and Rothko, whose huge works envelop your whole field of vision. When you look at this in the museum, it’s almost as if you’re entering it.

Carlozzi: Struth immerses you in his landscapes. And the way he uses space in this photograph is really complicated. It’s flat, making you search for the foreground and background.

Sally Dunning: Every time I look at it, I see something different.

Tom Dunning: Once I took a photo of my daughter standing in front of this photo, and it looked like she was actually in the jungle.

Zeng Xiajojun: Nine Trees, 2007-2010

Handscroll, ink, and color on Xuan paper, 27 3/16 x 389 in., Collection of Lucy Crow Billinglsey, BBA ’75, Life Member

Lucy Crow Billingsley: I think with art, you instantly react to something. It’s not a long, contemplative process for me. I loved this work immediately, and I love the blend of contemporary and traditional techniques. As China grows more and more as a world power, we’re going to see more contemporary Chinese art in the West.

Carlozzi: In the exhibit, this work is in a room that’s about drawing of all kinds. Then if you go around the corner, there’s a display of traditional Chinese jade owned by Lucy’s mother. So there’s a narrative here about vocabularies of drawing and about the act of collecting art.

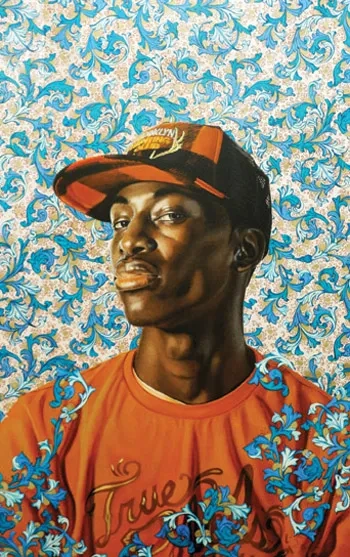

Kehinde Wiley: Gavin Study I, 2008

Oil wash on paper, 40 x 26 in., Collection of Brent Hasty, MA ’00, PhD ’07, and Stephen Mills

Bacigalupi: This young man is clearly contemporary, but there’s an elaborate filigree pattern behind him, like something you might see in 18th-century fabric. As a viewer, I would ask: why is the filigree leaching over into the contemporary subject? He’s living in the modern world, but the past is still there. You could draw a connection between the vintage filigree pattern and the plaid on his cap: that much of our present is inherited from the past.

Carlozzi: Wiley takes regular guys off the street and paints them heroically, in the style of kings and heroes. He makes us all feel worthy of a grand portrait.

Henri Rousseau: Exotic Landscape with Tiger and Hunters, 1907

Oil on canvas, 59.5 x 73.5 cm, Private collection

Bacigalupi: Rousseau was beloved by the modern artists like Picasso. He worked as a tax collector and painted on the weekends—he was untrained, and his naïveté was what other artists responded to. Among professionally trained artists, he was an exotic creature much like the tiger in this painting.

Carlozzi: Like the Struth photograph, the painting is flattened out. I put these together in the exhibition because the works talk to each other—a century apart, Rousseau and Struth were interested in the same idea.

Bacigalupi: With such a heterogeneous exhibit, it’s important to find points of access between works. The viewer is encouraged to compare and contrast.

Ed Ruscha: Futures, 2001

Acrylic on canvas, 82 x 120 in., Collection of Jeanne Klein, BS ’67, and Michael Klein,

BS ’58, LLB ’63, Life Member

Bacigalupi: Ruscha is a major player in the contemporary art world. In the 1960s and ’70s, he was making paintings out of things like grape juice, gunpowder, and blood.

Carlozzi: You see the word “future” twice in the painting—but then you’re looking at these ancient mountains. So there’s a great ironic contrast.

Bacigalupi: It’s a postcard-perfect kind of image, but then there’s this distorted text on top of it like a puzzle. What does it mean to put the text in that almost indecipherable way? There are more questions than answers.

John Atkinson Grimshaw: A View of Whitby Harbor, 1877

Oil on panel, 25 x 19 inches, Collection of Julius and Suzan Glickman

Julius Glickman: What I love about this painting is that it looks completely different depending on the light. We had it professionally lit. As you turn the lights up or down, the whole ambiance changes. I’m sure it will look different in the museum.

Collette Crossman: Grimshaw was painting while the aesthetic movement was going on in Victorian art. I wouldn’t say he belonged to the movement, but you can see its influences in his work. It’s very atmospheric, very moody.

Top right: Baron Francois Gérard: Jean Lannes, Duc de Montebello, Maréchal d'Empire, 1809-10

Credits: Bruce M. White (Ye Shall Inherit the Earth); Richard Green Gallery, London (Bellezza Pompeiana); Peggy Tenison (Unknown, Roman); Lora Reynolds Gallery (Gavin Study I); James Hart (Futures). All others courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art.