UT Researchers Are Unraveling the Origins of the Universe

The day Steven Finkelstein discovered the oldest galaxy ever seen by a human, he was holed up in a windowless room on the Forty Acres with several colleagues, surrounded by Costco snacks and staring at screens.

For days, Finkelstein and his colleagues had barricaded themselves in the room for 12 hours at a stretch, poring over the first data released from NASA,s recently launched James Webb Space Telescope. They were on the hunt for ancient galaxies that hold important clues about the origin of the universe, but just figuring out how to use the data from this brand-new telescope was proving cumbersome.

“The data doesn’t come down in a form where you can see the galaxies,” says Finkelstein, a professor of astronomy at UT Austin. “We knew there were discoveries to be found in that data, and I didn’t even really care if we were the first to publish. I just wanted to see it with our own eyes before someone else told the world what our data held.”

After days of puzzling over the data, their hard work paid off. No one shouted “Eureka!,” but Finkelstein remembers a tense excitement as the group pulled the image up on a big screen to appraise their finding. The actual image looked like a smudge on the screen, but the data pointed to an unavoidable conclusion: What they were looking at was the oldest galaxy ever discovered by several hundred million years.

Finkelstein printed out a picture of the galaxy (which still hangs in his office) and started walking around the astronomy department, showing it to anyone he could find. “I was like, ‘Do you buy this?’” he said. “I couldn’t believe we were seeing this thing. It was surreal.”

It would take another year for his team to confirm the finding with additional observations, which officially put a timestamp on the galaxy at 390 million years after the Big Bang. Finkelstein named it after his daughter, Maisie, to commemorate its discovery on her birthday.

Although Maisie’s Galaxy has since been dethroned as the oldest galaxy found by the Webb telescope, its discovery was a watershed moment in astronomy that has opened the early universe to a new era of discovery.

In 2024, The University of Texas at Austin launched the Cosmic Frontier Center to capitalize on the new research made possible by Webb, and within less than two years, the CFC has already made several blockbuster discoveries that are fundamentally changing our understanding about the origin and evolution of the universe.

When NASA launched the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) in late 2021, it marked a turning point for astronomers who study the early universe. For three decades before Webb, researchers primarily relied on the Hubble Space Telescope to study the early universe. Although Hubble excels at capturing optical light, which is perfect for observing nearby galaxies, its sensitivity drops off as one looks further out into spacetime.

The universe’s constant expansion causes the light from more distant galaxies to be stretched into longer wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum. This phenomenon, known as redshift, means that distant galaxies racing away from us appear redder than they actually are, and the effect grows more pronounced the further back one looks in time. Redshift is measured using a number that corresponds to how much the light’s wavelength has been stretched compared to when it was first emitted. A galaxy, blackhole, or star with a high redshift number is farther away and receding faster than an object with a low redshift number. At redshifts greater than 10, light from a galaxy is shifted fully out of the visible, into the infrared regime.

Although Hubble, which is primarily sensitive to visible light, struggled with imaging galaxies much older than about 1 billion years after the Big Bang, hunting for the earliest galaxies in the universe is just the type of challenge that Webb was built for. The infrared-optimized Webb can now observe galaxies at redshift 14 and beyond, which were formed about 270 million years after the Big Bang. To put this in perspective, the highest redshift object ever found by Hubble was around redshift 10 and was traced to around 500 million years after the Big Bang.

“Webb is extremely sensitive to wavelengths of light that are beyond Hubble’s grasp, and the mirror’s collecting area is also several times larger,” said Anthony Taylor, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cosmic Frontier Center. “It’s completely changed the field.”

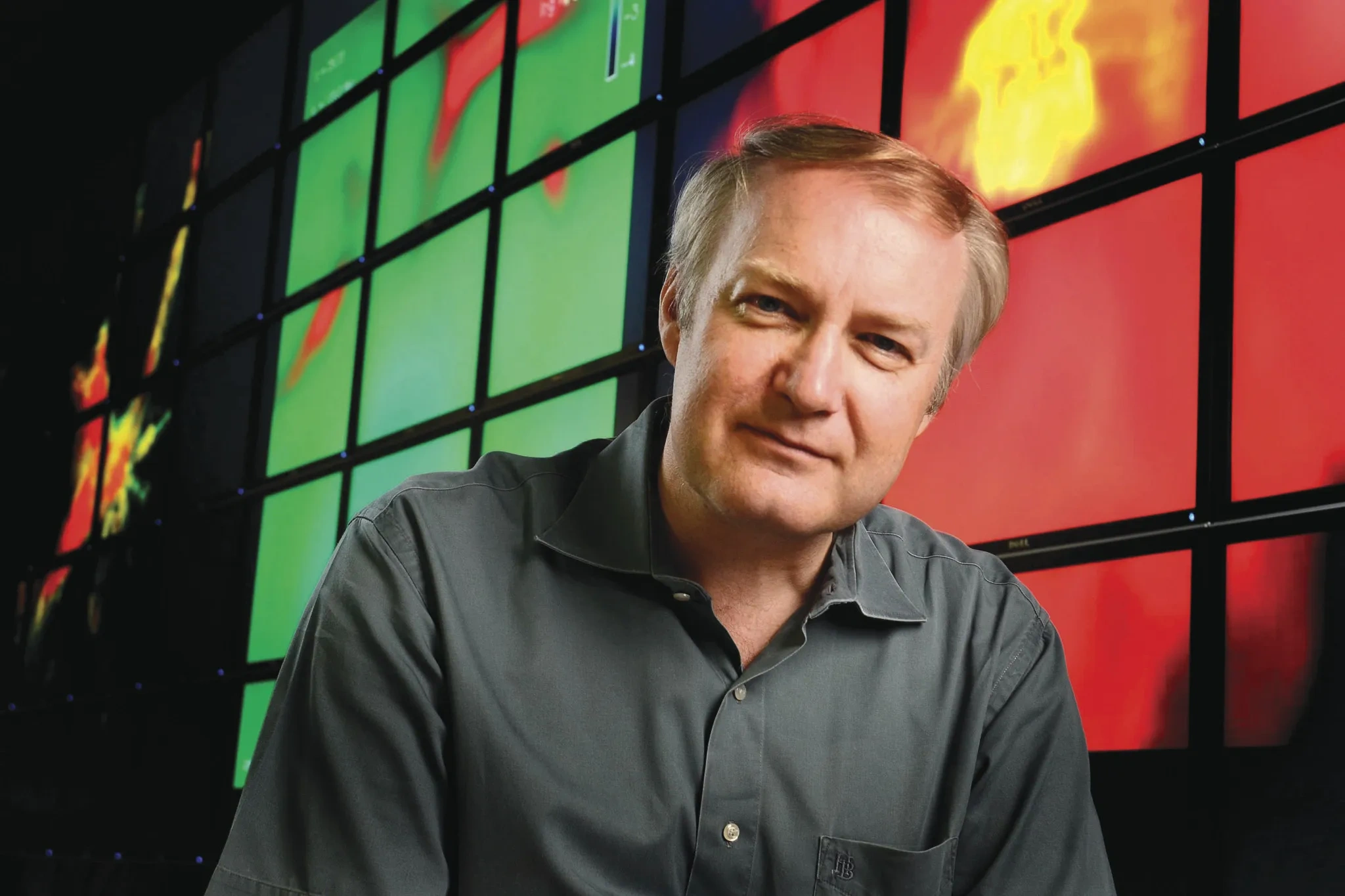

Volker Bromm, a professor of astronomy and co-director of the CFC, has spent his career studying star formation in the early universe. This is, fundamentally, an exercise in understanding our origins, but by understanding how something evolved from nothing we might also be able to better understand how the universe will change in the future. When Bromm joined UT’s faculty in 2004, Hubble was still the primary tool for studying the early universe, and the limitations of its instruments meant that exploring the earliest phases of the universe was still mostly a theoretical exercise. He and his colleagues would start with observations of relatively mature galaxies and work backwards using supercomputers to create a model of the universe’s evolution that matched their observations from Hubble.

Those models told a tidy story of the universe’s early history: darkness, then gravity’s slow pull on primordial gas, which eventually coalesced into the first stars and galaxies. In this model, the universe slowly pieced itself together over billions and billions of years, with small galaxies gradually becoming large galaxies and dying stars creating small black holes that eventually became large black holes.

Webb’s launch changed everything by making galaxies in the early universe directly observable for the first time. And when Webb started sending back data, suddenly those neat theoretical models crashed headlong into a messier and more mysterious reality.

The first major surprise from Webb was the sheer number of galaxies that existed in the early universe. In 30 years, Hubble had found only one galaxy beyond a redshift of 10. “Did that mean there weren’t a lot of galaxies at a redshift of 10 or beyond?” says Finkelstein. “We weren’t sure.” But within days of looking at the first release of Webb data, the UT team found one above redshift 11. They ultimately found more than 90 very high-redshift galaxies in that first data set from Webb. “We learned that the early universe was producing more galaxies and stars than any of our expectations before [Webb] was launched,” Finkelstein says.

The big question is how that happened. One possibility is that early galaxies were more efficient at turning gas into stars. The Milky Way only converts about one percent of its gas into stars, but if the early galaxies were just a bit more efficient—turning, say, 10 percent of their gas into stars—that could account for Webb’s observations. Or maybe the stars in those galaxies had more exotic chemistries that make them burn, hotter and bluer, which would make them brighter—a mystery the CFC is working to solve.

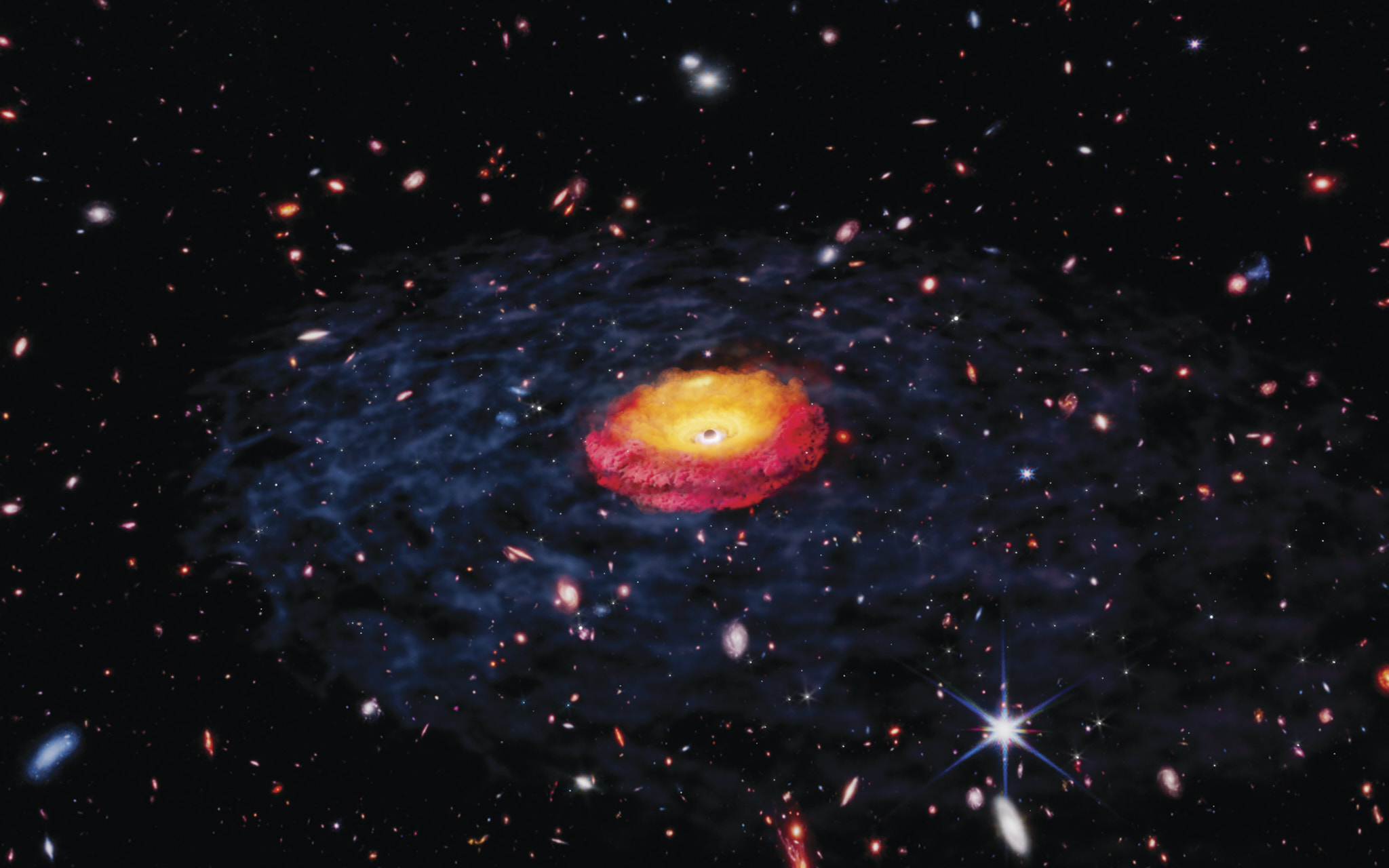

The second surprise from Webb was even more shocking. Although theorists assumed that small black holes must have existed in the early universe, the Webb data showed that supermassive black holes appear to be extremely common in the early universe, and many of them are more massive than anyone thought possible.

Earlier this year, Taylor published a paper identifying the most distant black hole ever confirmed, dating back 13.3 billion years to when the universe was 500 million years old. The galaxy where the black hole was discovered is called a “Little Red Dot” galaxy, part of a new class of galaxies discovered by Webb that formed in the first 1.5 billion years of the universe. As their name suggests, these galaxies are compact, red, and unexpectedly bright.

Taylor found the black hole by looking for a specific signature in the galaxy’s spectrum called a broad line. When atoms swirl around a black hole at high speeds, the light they emit gets stretched and compressed by the Doppler effect, broadening a single wavelength into a wide band. “There aren’t many other things that create this signature,” says Taylor. It was a smoking gun that suggested that the brightness of Little Red Dot galaxies comes from supermassive black holes rather than from an abundance of stars. “It’s left a lot of us pleasantly puzzled on how [the universe] could create this monstrously sized object in so very little time,” says Taylor.

In our local universe, all large galaxies have a black hole at their center. The black hole is typically a small fraction—about 0.1 percent—of the mass of all the stars in the galaxy. But some of the early black holes are similar in mass to the stars in their galaxy, meaning that some early galaxies are close to 50 percent black hole.

According to standard cosmological theory, black holes should start small. When a massive star dies, it might create a black hole with around 10 times the mass of our sun, growing over time as it pulls in more matter. But Webb is finding black holes that have a million or 10 million times the mass of the sun very early in cosmic time. According to standard theories of black hole formation, there simply isn’t enough time for them to grow so large.

“One of the hottest questions that is at the forefront of what we’re doing is how did the first supermassive black holes emerge in the universe?” says Bromm. “As we push closer in time to the Big Bang, we’re finding supermassive black holes, and it’s a real stress test for our standard model of cosmology.”

One theory Bromm and his colleagues have developed involves what they call “heavy seeds.” Rather than dying stars, this theory posits that unique conditions in the early universe caused massive clouds of primordial gas to collapse directly into black holes that are 100,000 times more massive than our sun. This would skip the baby steps and go straight to the monster.

In October, the CFC team got results from observations specifically meant to test this theory. A CFC postdoctoral fellow had a result suggesting that by 1 billion years after the Big Bang, the distribution of black hole masses showed no clear pattern. A graduate student built a theoretical model predicting that if you looked further back in time, you’d see a bump in the distribution at about 100,000 solar masses, the signature of a heavy seed. The team rapidly put in a proposal to the Webb telescope director for observing time to test the prediction. The proposal was approved, and when the data came back in October, there was the bump, exactly where the model predicted.

Webb has unleashed a torrent of surprising discoveries about the early universe that clash with our current models of how galaxies, and the universe writ large, have evolved. The flood of new data released by Webb needed a new kind of collaboration between people who observe the sky and people who model it to make sense of these contradictions. “What makes CFC really unique is that we have theorists and observers talking to each other every week,” says Taylor. “That allows us to iterate on these things way faster than anyone else.”

Although the exact discoveries were a surprise, the steep change in observational capabilities was not. It was clear that solving the mysteries of the early universe would require a unique blend of expertise, and over the past decade, UT’s astronomy department has quietly assembled many of the world’s leading observational and theoretical astronomers whose expertise encompasses every aspect of galaxy formation. As a result, the CFC team has led or been part of collaborations accounting for more than 20 percent of all Webb observing time to date, which is among the highest fraction of any institute, academic or federal, competing for time on the most in demand instrument in astronomy.

“The reason we started the CFC is because we had a confluence of faculty members at UT working on galaxy formation on both the observational and theoretical side,” says Finkelstein, who serves as the center’s director. “We wanted to find a way to become greater than the sum of our parts. The combination of observers and theory is our biggest strength.”

This collaboration also extends beyond the walls of the astronomy department to the Texas Advanced Computing Center, which provides the supercomputing power needed both to analyze Webb’s massive data sets and to run the complex simulations that help explain what the telescope is seeing.

To support its rapid pace of research, the center has also established a postdoctoral fellowship that funds new positions at UT for researchers who have recently received their PhD in areas relevant to the center’s research. “Postdocs are really the ones who get the work done,” says Finkelstein. “They’re experts in their field, they’ve done their PhD, they’re fully trained, and they have independent research skills.”

In August, the CFC announced five recipients of its second postdoctoral cohort. Among them is Archana Aravindan, who joined the CFC in September after finishing her PhD at the University of California, Riverside, where she specialized in finding black holes in dwarf galaxies.

Black holes in large galaxies are easy to spot because they’re powerful and energetic. But in smaller galaxies, the black holes are weaker, and stars can be just as energetic, making the black hole signature hard to pick out. Because many of the galaxies that Webb is finding are small and comparable to dwarf galaxies, Aravindan is interested in studying nearby galaxies as local analogs of more distant galaxies so she can see in high resolution what would look like fuzzy dots in Webb data.

“We’re trying to bridge the gap between resolved studies of the local universe versus studies in the high-redshift universe,” says Aravindan. “I’m interested in looking for black holes in these galaxies, trying to understand what a black hole is doing to these galaxies and how that helps us understand how the galaxies of the early universe evolved.”

The CFC’s research also extends beyond postdocs and faculty. The Galaxy Evolution Vertically Integrated Projects (VIP) program brings undergraduates into the research process, giving them hands-on experience with real Webb data. As part of VIP, undergraduates participate in a five-semester program. In the first semester, they do a crash course in Python programming and analysis for astronomical data. During the second semester, they figure out their research projects. Then for the next three semesters, through the end of senior year, they do research. “They’re working with real data and doing real research,” says Taylor.

As an example, Taylor points to one undergraduate student who is currently looking for active galactic nuclei in a brand-new Webb data set, developing her own algorithms and code. Although the primary goal of the program is to help undergraduates get hands-on research experience to decide if a research career is for them, many students have also published their work in peer-reviewed papers.

In its first two years, the CFC has already made a number of discoveries that have fundamentally changed our understanding of the early universe. But for Finkelstein and his collaborators, this is just the beginning.

In the early 2030s, a telescope the size of a baseball diamond will open its eye in Chile’s Atacama Desert. The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) will dwarf every optical telescope ever built so that it can gather light from the edge of time. To date, UT has committed more than $110 million to the development of the GMT, and the work being done at the CFC today is positioning UT researchers to be at the forefront of the next great revolution in astronomy.

“The GMT is going to be making discoveries left and right,” says Finkelstein. “We hope the CFC is leading the scientific charge when the GMT comes online.”

Until then, the CFC team is focused on solving the mystery of how the first supermassive black holes formed. “The origin of the first black holes is a problem that is solvable in the next five years,” says Finkelstein. “I think UT has the right combination of observer and theorist expertise to be the one to solve it. You only get to write the textbook about how the first black holes were formed once, and we’re hoping that it’s us.”