Good Reads Q&A: Meet the Michener Graduate Earning Critical Acclaim

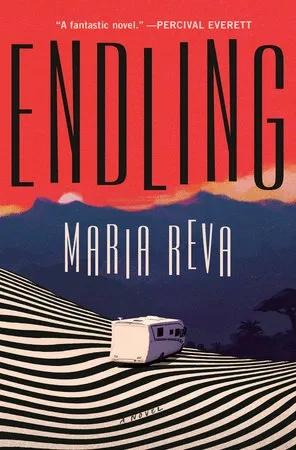

It’s a classic setup: A malacologist, a Ukrainian activist, and a Michener fellow walk into a bar. (Or something like that.) But Endling, the Booker Prize–longlisted novel from Maria Reva, MFA ’18, is no joke.

Reva’s first book, Good Citizens Need Not Fear, hit shelves on March 10, 2020—mere hours before the World Health Organization named COVID-19 as a global pandemic. Her book tour and all post-release press (crucial for a debut novelist) were over before they could even start. Then two years later, she watched as her native Ukraine was invaded by Russia.

These historic events made their way into Reva’s work, though not as anyone might have expected, least of all the writer herself. She had already been at work on a novel with two headstrong Ukrainian women at its center: Yeva, a rogue snail conservationist, and Nastia, who hopes to disrupt her country’s booming romance tourism industry from the inside. Their storylines would encounter further complications, as Reva decided to move them behind the frontlines in the early days of the war. She also included metafictional, first-person narrative about the construction of the book, among other breaks in traditional form.

The Alcalde caught up with Reva between tour engagements and rave reviews to learn more about why she writes and how this idiosyncratic book came to be.

How did you make it to Michener?

I was working odd jobs after undergrad … doing part-time marketing and part-time construction work. But I really wanted to write. I applied to MFA programs, including the Michener Center as a longshot, and I got rejected everywhere. Like, I didn't even make the first round. But I got waitlisted at [the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa], and that gave me just enough encouragement to keep going. And so I quit one of my jobs, and I worked harder on my portfolio, and in my second time around, I got into several programs.

But when I got an email from the Michener Center saying that I'd gotten in, I actually thought it was a mistake. There's lots of Maria's out there, and maybe they got the wrong Maria, you know? So then, when they called me, I asked them, “I just want to make sure you're talking to the right one.” And they're like, “We take these phone calls very seriously. So yes, you're the right one.” It was truly one of the best things that's happened to me.

The first story in Good Citizens Need Not Fear, called “Novostroïka,” that's actually the story that got me into grad school. It's the story that was published in the Atlantic. It got me an agent [and] got me a good residency as well. So it was a story that opened up a lot of things for me, and it set off the rest of the collection as well.

And then the pandemic hits as the collection releases. How did you process that?

It was certainly a shock. I had a book tour in the U.S. that was planned, and everything got canceled, of course. It's still sad, but very, very understandable.

When Endling was about to come out, I think I was still shell-shocked from the first book. So anything that was planned, I did not believe it would happen. When my publicist told me that Seth Meyers wanted to have me on his show, I smiled and nodded … It didn't sink in until I was at the NBC Studios getting my hair and makeup done. I thought, Oh my God, it's actually happening.

Where did Endling begin in that timeline from 2020 to 2022?

It was actually 2018, my last year living in Austin, that I started the book … When Russia invaded Ukraine, I was already four years into the novel, and at that point I did not know how to continue it … How do I keep writing a book when its setting is being destroyed in real time? I was obsessed with these questions of, what is the role of fiction in today's world? How do I write about conflict from abroad? Can I do it? Do I have a right to do it?

I write from a place of obsession … [so] I decided to fold all of those questions into the fabric of the novel and draw back the curtain for the reader so that they could come along on that exploration with me.

Did your initial writing of these disparate pieces differ from how you eventually constructed the book?

It's a question of content and container. I write opera scripts as well, and I'm always asking the question of, does the container fit the form? … I think that way in my prose as well, even on a chapter-to-chapter basis. If there's a chapter that doesn't quite work written in straight prose, then I try other containers for it.

There is a chapter [in Endling] that is written in meeting minutes that was initially written as prose. Because there are so many pieces of information that these [characters] have to process while trying to tamp down their own panic, I thought, This needs to be written in a different way. These women are trying to create order out of utter chaos, and you feel the panic seeping between the bullet points, instead of just writing that they are panicked.

Has first-person narrative appeared in your work before?

That is new for me. The nonfiction, memoiristic bits came about when I was getting ready to go back to Ukraine about a year into the full-scale invasion … There was this sense of quiet terror in me about going to Ukraine. I think I was suppressing it, but it was there. All I could write were these journalistic entries about preparations for the trip, and then while I was there, I was keeping a kind of blog to record everything. I think it was almost this psychological tool to keep reality at bay. If I could put my reality into words, I could keep it at a distance, and life became material I could mold.

I realized these various entries and reflections were connected to the novel because it is me, the writer, who is attempting to write this book. I wanted to express that nothing is written in a vacuum. There is also a living human under the novel who is trying to construct it with their own conundrums, their own questions.

What is your understanding of fiction’s role in history?

Well, for me, fiction is a way … enter history through the everyday lives of ordinary people. The epigraph of the book is from [the writer] Chus Pato: “People don’t live history, they live their lives. History is a catastrophe that passes over them.” It felt like that during the pandemic as well, right? We were all living history, and we knew that there would be books written about it later. But we were also trying to live our small, mundane lives. Human experience is the construction—or the addition—of all of our lives together. I want to be a witness to that.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

CREDIT: Anya Chibis