Exploring UT's Living Learning Lab in the Heart of Hill Country

Descending into the mossy, limestone canyons hidden within UT’s Hill Country Field Station feels like passing through a time warp. Together with a group of eager, early-morning birders, we wander down a rugged pathway, discovering a pristine natural world undisturbed by human industry. Necks adorned with binoculars and water bottles in tow, we’re on a collective mission to spot avian travelers passing through the skies ... hopefully.

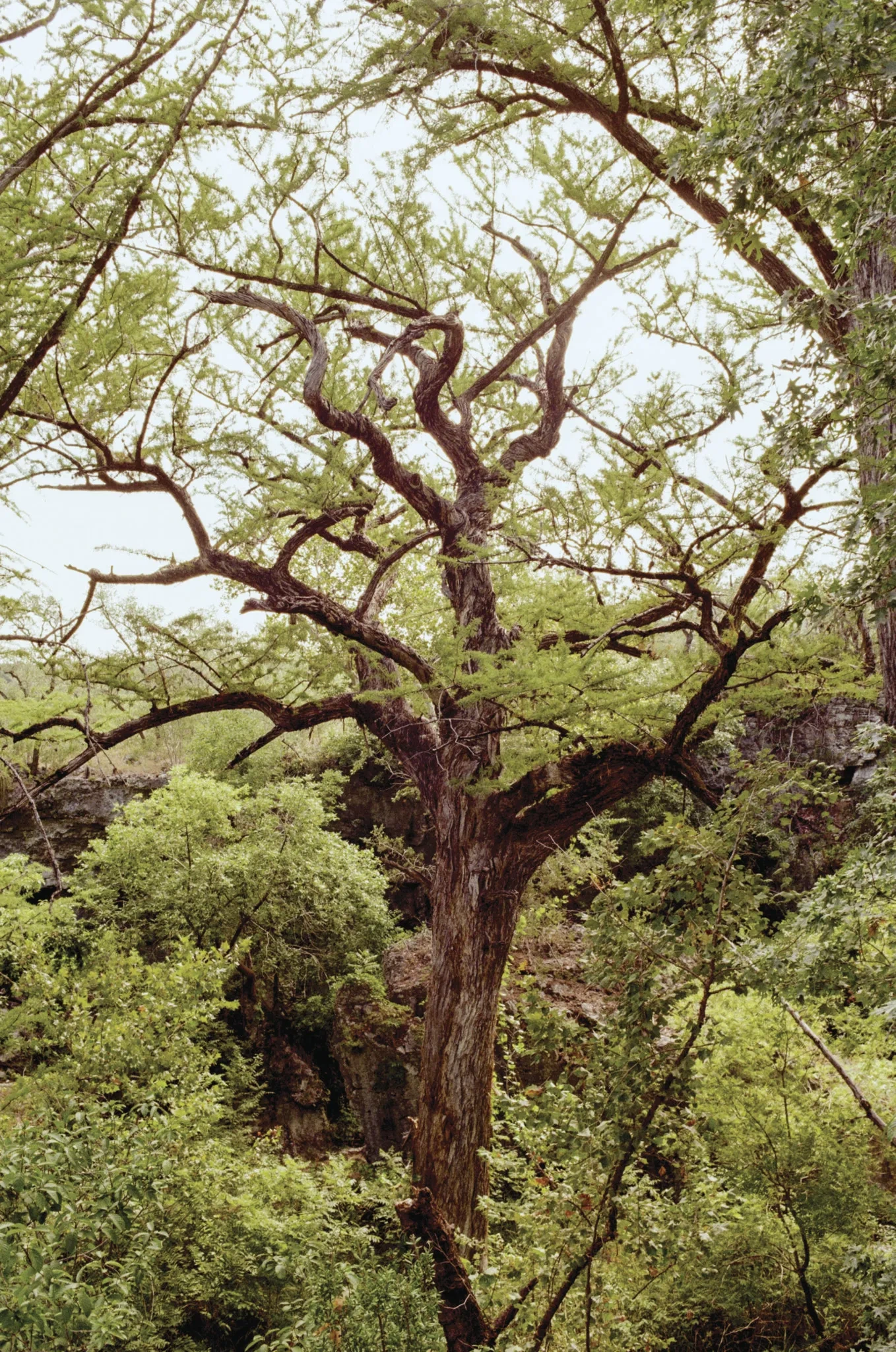

Central Texas is a bird migration superhighway, but it’s a bit early in the season—we know—and the air traffic is thin. We traipse across the soft carpet of fallen juniper needles, winding our way around the twisted trunks of towering bald cypress trees, hiking past trickling spring-fed creeks. I ogle at the purple-dotted American beautyberry branches muscling through the cracks of towering limestone. The ecological wonders below my feet beckon my attention down, but the faint birdsongs above hold the promise of a peek. It feels impossible to focus. Someone from our group oohs. We stop suddenly. Tilt our heads up in unison, press our binoculars to our eyes—and collectively spot a fluttering white-eyed vireo. Check.

Organized through a partnership between Travis Audubon Society and UT, the bird walk offers a rare chance for Audubon members to explore a private conservation easement. The programming is an effort of the Hill Country Field Station, the University’s newest addition to its Texas Field Station Network, housed under the Biodiversity Center. A gift from the Winn family of Dallas, including Steve Winn, BS ’69, and his wife, Melinda, the land serves as a living laboratory in a place so biologically unique that the 1,400-acre site is home to rare and endangered species found nowhere else in the world.

Thomas Schiefer, the recently anointed field station manager, guides us toward the banks of the Pedernales River, sharing some of his favorite features of the dense and delicate ecosystem along the way. Pointing to the supine remnants of a tree fallen long ago, he tells us about the leafcutter ants that inhabit the log. They’re fascinating little farmers, he says, whose active colonies draw armadillos in search of food. His amazement seems as fresh as ours, as if he, too, is witnessing the wonders of the landscape for the first time.

As we make our way to the river, we’re transported once again. We emerge from the woodlands to find ourselves standing on the stoney, sun-drenched banks of the Pedernales. Schiefer spots a snake across the way, bathing in the intense morning light. We stare at the slithering creature through our binoculars as a ringed kingfisher glides through the view of my binoculars. Check.

After the bird walk, Schiefer takes me on a private tour of the field station property in his Toyota truck—air conditioning blasting as the September heat rises. Schiefer started his new position in the spring—with the purpose of strengthening community outreach and becoming the chief steward of the land. “My boss told me that my first job was to hike, bike, and explore every inch of the property,” he says. “Five months later, I still haven’t seen it all.” But certainly not for lack of effort. Schiefer is a passionate naturalist and a former teacher—he feels genuinely connected to the land. And as a native Texan, he’s been exploring the Hill Country his entire life.

As we cruise through the rolling savannas, Schiefer explains how the field station property sits at a rare ecological crossroads. It rests on the Edwards Plateau ecoregion, but its borders touch the Blackland Prairie, the Chihuahuan Desert, the South Texas Plains, the Cross Timbers, and the Post Oak Savanna. This intersection creates a biodiversity hotspot. The extreme elevation shifts also create an environmentally rich footprint: The land sinks to 600 feet along the river and rises to nearly 1,200 feet at its rigid peaks.

Schiefer stops the truck and points beyond the grassland to the ash juniper trees lining the horizon—a home to endangered golden cheek warblers. He gestures toward the gorgeous live oaks towering over the sea of bluestem grasses. He directs our view to the deep-green crowns of the ancient bald cypress trees peeking above the low-lying edges of Roy Creek. “So 1,400 acres is already big,” he says, “but what makes this an even bigger property is the diversity of the landscape.” A reptile critter skitters across the ground, “Oh, there’s a six-lined race runner, a cool little lizard!” Schiefer’s tour guide skills seem effortless.

Beneath the diverse topography lies the lifeblood of the Hill Country: water. Rainfall here vanishes through the porous limestone into the Edwards Aquifer, where it seeps downward into the Trinity Aquifer, creating an intricate system of rivers and springs that serve as the main water source for millions of Central Texans. This type of karst terrain creates the natural wonders so often associated with the Hill Country: trickling streams spilling over collapsed caves, forming irresistible swimming holes; mossy, limestone grottos; calm, flowing creeks flanked by soaring cypress trees. While beautiful, the landscape is extremely vulnerable to dangerous flash flooding due to its shallow soil and steep hills.

Kenneth Wray, managing director of the Texas Field Station Network, says because of the aquifer’s environmental importance and its rare subterranean habitats, the stakes for research and conservation are high. With large population increases, he says, come the problems. “We have increased demands on resources, mainly hydrological,” Wray says. “And with that comes waste, pollution, and sewage. It’s going to be really important to not only study, but monitor long-term changes in that ecosystem—which is very delicate.”

The Hill Country Field Station is the newest in UT’s Texas Field Station Network, which includes Brackenridge and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, Stengl Lost Pines in Smithville, the Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas, and the McDonald Observatory in West Texas. More than 1,000 acres of this land are part of a conservation easement, meaning it can never be developed. About 10 acres are dedicated to future field station facilities. While no plans are final yet, this area could include modern labs, housing for visiting students and faculty, and spaces designed to anchor teaching and research.

Though the facilities are still in development, University scientists have hit the ground running. Sixteen research projects are underway. Notably, Professor David Hillis, director of the UT Biodiversity Center, is conducting a large-scale study on the site, looking at microbes in the water and soil that are critical to the health of plants, animals, and humans. Hillis has already discovered a new salamander species, while UT entomologist Alex Wild recently identified two new species of ants. Wray says these types of discoveries are key reasons for conservation. “If we lose those species now before we discover them, that’s a huge loss to humanity, to human health, and to human economies.”

As research ramps up, Schiefer is focusing on public outreach and partnerships. For K–12 teachers, the land could become a hands-on classroom, introducing students to ecology and conservation. He’d like for the field station’s activity to expand beyond biological research. “The last thing you want at a field station is [for it] to be unused,” he says. Schiefer will also manage the facilities, once they are complete.

“Our perfect week could start on Monday with an Audubon walk,” he says. “Then Tuesday, we have an art class come out here from UT. On Wednesday, we could have a history class come out and talk about some of the historical people who lived here—starting with the Native Americans, to the Germans who came here, to the cedar choppers who lived here, and up to modern day. And then the next day could be students from the biology department learning about plants.”

Wray agrees the field station should be open to interdisciplinary engagement. “The idea here is that we’re utilizing our field stations on multiple levels,” he says. “Not just for research, but for education and outreach—field trips, training teachers, and bringing in private landowners to understand research that may benefit their properties.” That vision is backed by the philanthropy of the Winn Family Foundation, which donated the land, underwrites staff positions, and provides annual research grants.

Wray believes the investment will pay dividends in drawing new talent. “I think this opportunity really does attract the attention of world-class researchers to want to come to UT and, more importantly, young students, whether it be undergraduates or graduate students from across the globe who will come here and take advantage of these world-class facilities at this University,” Wray says. “It’s really exciting for researchers to be able to study a lot of different systems, essentially in their backyard. Many universities can’t offer that kind of opportunity,” he says.

Both Wray and Schiefer see the station as an accessible laboratory—one where artists and scientists, landowners and students, can all encounter the Hill Country’s ecosystem firsthand. “Who knows when the next species that’s found is going to be the cure for cancer, or a microbe that cleans up pollution,” Wray says. By instigating cross-collaboration, the odds for a sustainable future seem more attainable in a time when the stakes couldn’t be higher. “Extinction is forever,” he says. “Once we lose that genetic variant, that ecosystem, that species, we’re not getting it back.”

David Vanden Bout, dean of the College of Natural Sciences, says the land provides an invaluable learning opportunity. “Biologists say field stations like this are among the best tools we have for studying long-term challenges facing our planet and understanding their impact on life and natural resources around us,” he says. “Students and alumni often tell us that what they learn at these sites is one of the most valuable parts of their education here. We’re lucky at UT to have donors like the Winns who understand that investing in the care, study, and protection of these spaces translates to lasting, meaningful benefits—for our science, our students, and the State of Texas.”

As Schiefer and I drive along, we stop to gander at a tattered wooden sign, likely a remnant from an old summer camp. “No littering, smoking, or rock throwing,” it says. Schiefer laughs, “It’s funny that smoking and rock throwing are on the same sign, like you’re either too young to smoke or too old to throw rocks.” We pass a cluster of post oak trees. They rarely grow this far west, Schiefer says. We talk about grasses and birds. He lists the wildlife spotted on the land in recent months: wild turkeys, bobcats, mountain lions, porcupines, white tail deer, grey foxes. He shows me some of the most magnificent water-filled grottos I’ve ever seen.

We stop at the edge of Roy Creek, where a bald cypress ascends out of the water. The rings inside the trunk date it back to the 1600s, he says. Schiefer and I stare at the majestic tree for what feels like an eternity, or maybe just a moment. That’s the wonder of this place—its timelessness.

For Schiefer, managing the Hill Country Field Station is not just the job of a lifetime, it’s a responsibility to steward the land. Together, with the help of UT’s dedicated scientists and the Winn family’s philanthropy, the field station is charting a path where research and community converge—and where the University can help preserve a fragile, resilient landscape whose future is still being written.