UT’s Treasured Dinosaur Trackways are Getting a New Home

The ferocious, bipedal dinosaur probably didn’t think too much about the scientific significance of the moment when it was stalking its prey through the muddy tidal flats of prehistoric Texas.

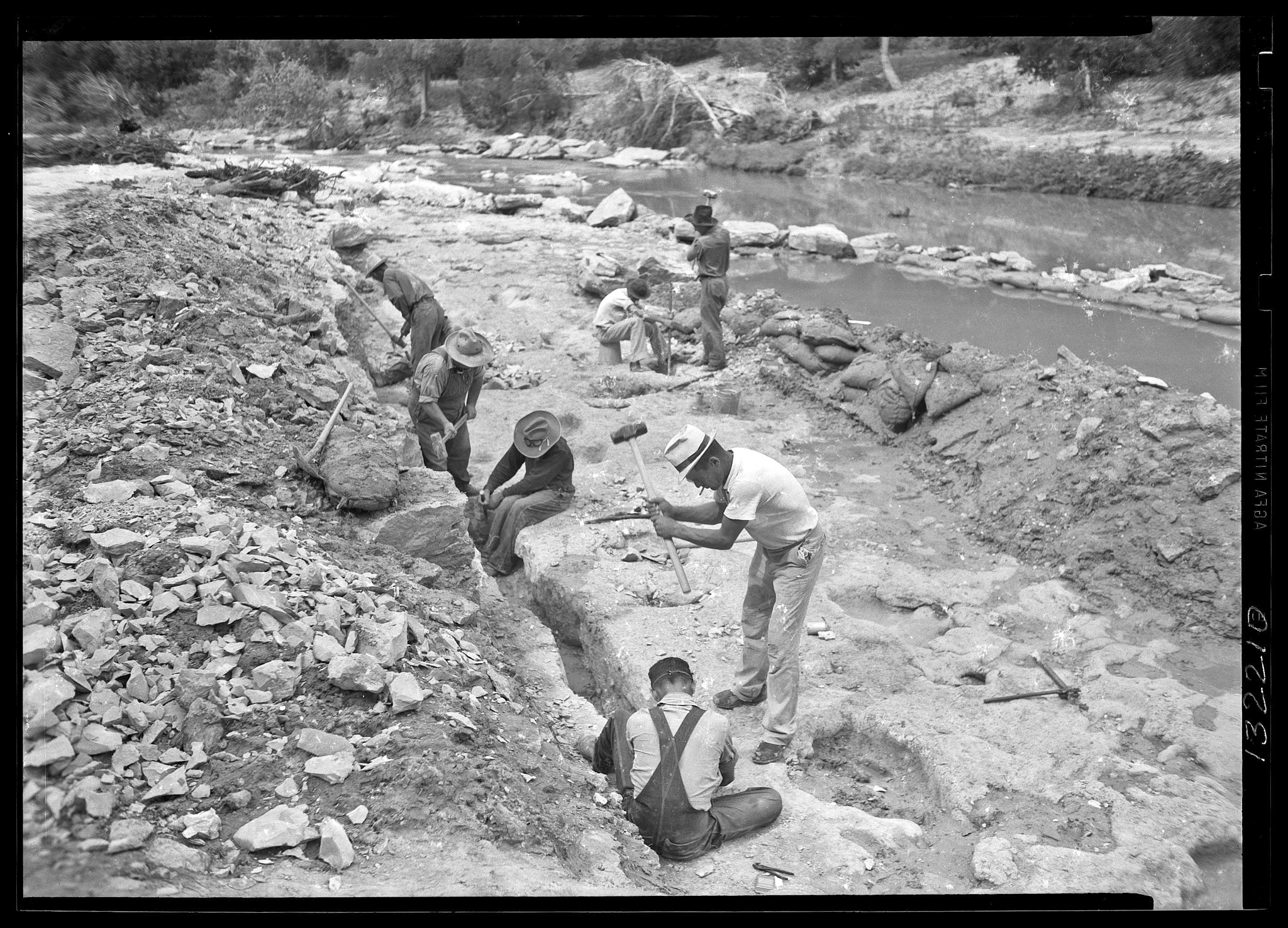

But the dinosaur was indeed creating one of the state’s most significant prehistoric treasures: rare, 113-million-year-old trackways—or set of fossilized footprints.

UT’s Texas Science & Natural History Museum is home to those trackways that were discovered near Glen Rose in the 1930s by paleontologist Roland T. Bird. But chances are you haven’t seen them or even known that they exist on campus.

The exhibit, built in 1940, closed to the public in 2013, when the modest limestone structure enclosing it came into disrepair. But thanks to a recent bolster of support from the University, and at the urging of conservation experts, the museum is embarking on a transformational project to restore and rehome the fossilized footprints. Fundraising is underway for the construction of the new Dinosaur Trackways Building and the building is expected to be completed in 2027.

“We’re really determined,” Carolyn Connerat, BS ’80, Life Member and managing director of the Texas Science & Natural History Museum, says about the multi-year conservation project. “How do we fix the tracks and create an engaging, educational experience for visitors to see them?”

Connerat, who has worked at UT since 2005, was hired by the museum in 2022 to help the struggling campus entity find its way after years of shrinking funds and a temporary closure. The museum reopened in 2023 with a new leader, a new name, and a new vision. Restoring the dinosaur trackways exhibit was part of the vision.

“We’ve turned the corner,” Connerat says as we tour the museum on a scorcher of a Tuesday. “We’ve had more than 100,000 visitors come through and hundreds of school groups, K through 12, doing field trips and tours.” We weave through the crowds of people (young and old) milling about, gazing at ancient bones puzzle-pieced together, resurrecting lifeforms long, long gone.

Connerat’s enthusiasm is contagious as we walk through the museum’s Texas Transformation Gallery which showcases 600 million years of life in the Lone Star State. She shares some of her favorite fossils discovered here in Texas: A glyptodont (think giant armadillo) was found outside Corpus Christi. A scimitar-toothed cat (think sabretooth) was discovered in a cave near San Antonio. A plesiosaur (think massive, scary marine reptile) was found near Shoal Creek in Austin. “That’s a real dinosaur femur. Feel free to touch it,” she says as we walk by a massive leg bone. “Did you know this is fossilized poop?” pointing at another exhibit.

Connerat guides us outside to where the old dinosaur trackways exhibit stood for more than 80 years. In its place now are a pile of limestone blocks, tarps stretched across the ground, and a small construction crew working carefully behind a chain-link fence.

I meet Darryl, who is wearing a hard hat and earnestly studying some blueprints, at work on the excavation process. He asks me if I “want to see,” then smiles as he lifts the corner of a tarp to give me a peek. There they were: the footprints of dinosaurs embedded deep into giant stone slabs, just sitting there, on the ground, atop a hill of the Forty Acres.

“Originally, we thought we would just take the building down, keep [the tracks] where they are, and build a new building around them,” Connerat explains. But that wasn’t possible. To stay preserved, the slabs need moisture control and climate control—crucial factors that the Work Projects Administration crews simply didn’t consider when they were first building the museum. Over time, water crept up through the soil, the building shifted, and the whole scenario put the specimens and visitors at risk.

A few weeks after my visit, the trackways were hauled to a lab in Maryland to undergo extensive restoration work by Evergreene Architectural Arts. The tracks will return to Texas next year for installation in their new 2,000-square-foot, climate-controlled, state-of-the-art exhibit building.

The future Dinosaur Trackways Building will offer an ideal environment for the fossilized footprints not only to endure as a scientific specimen, but to finally delight the masses. For the first time, visitors will have 360-degree access to the tracks, which Connerat says will open the doors for discovery, research, and renewed interest.

“These tracks give us a snapshot of behavior, not just anatomy,” Pamela Owen, paleontologist and the museum associate director, explains. “It’s rare to get that from the fossil record.”

While the trackways themselves are rare for their utility as reference points for adjacent research, Texas is rich in prehistoric remnants. During the Cretaceous Period, between 143 to 66 million years ago, much of the state was underwater. And what is now North Texas used to be an ancient shoreline—a prime environment for preserving prehistoric activity such as dinosaur footprints.

But what exactly was happening when the trackways were captured? Owen, PhD ’00, says studying tracks is tricky—like a forensic scientist’s analyzing a shoeprint—but the clues are compelling.

The probable trackmakers were Sauroposeidon, a quadrupedal, plant-eating sauropod (think Brontosaurus), and Acrocanthosaurus, a bipedal, carnivorous theropod (think Tyrannosaurus—yikes). Because the sauropod’s giant, round prints are accompanied by three-toed prints, paleontologists hypothesize that the predatory therapod was stalking it.

(Sauroposeidon, by the way, is the official state dinosaur of Texas, and Acrocanthosaurus is the state dinosaur of Oklahoma. No wonder these two species weren’t exactly friends.)

While the scenario was likely terrifying for poor Sauroposeidon, the action of it all created a paleontological artifact that will long serve as a source of scientific interest and human curiosity. And, who knows, maybe it was lucky that day.

Soon, visitors will be able to walk alongside those giants who left their mark on the land and on science long ago. And the Texas Science & Natural History Museum will proudly share the restored dinosaur trackways exhibit with generations to come.

“The museum holds the tracks in trust for the people of Texas,” Owen says. “It’s not just for scientists. They are resources for all of us.”

CREDITS: Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History; Texas Science & Natural History Museum; Cheung Chungtat