Lorne Michaels Gives the Harry Ransom Center a Blockbuster Archive

Steve Wilson, BA ’79, BS ’95, was a UT freshman in 1975, living in the Jester Center. Back then, on your average weekend night, you wouldn’t find too many people in the Jester West TV room. Fraternity parties, Sixth Street, and the Austin music scene all beckoned over watching whatever might be on the dormitory’s boxy, 21-inch tube set.

But then, Wilson says, “there came to be this show on Saturday nights.”

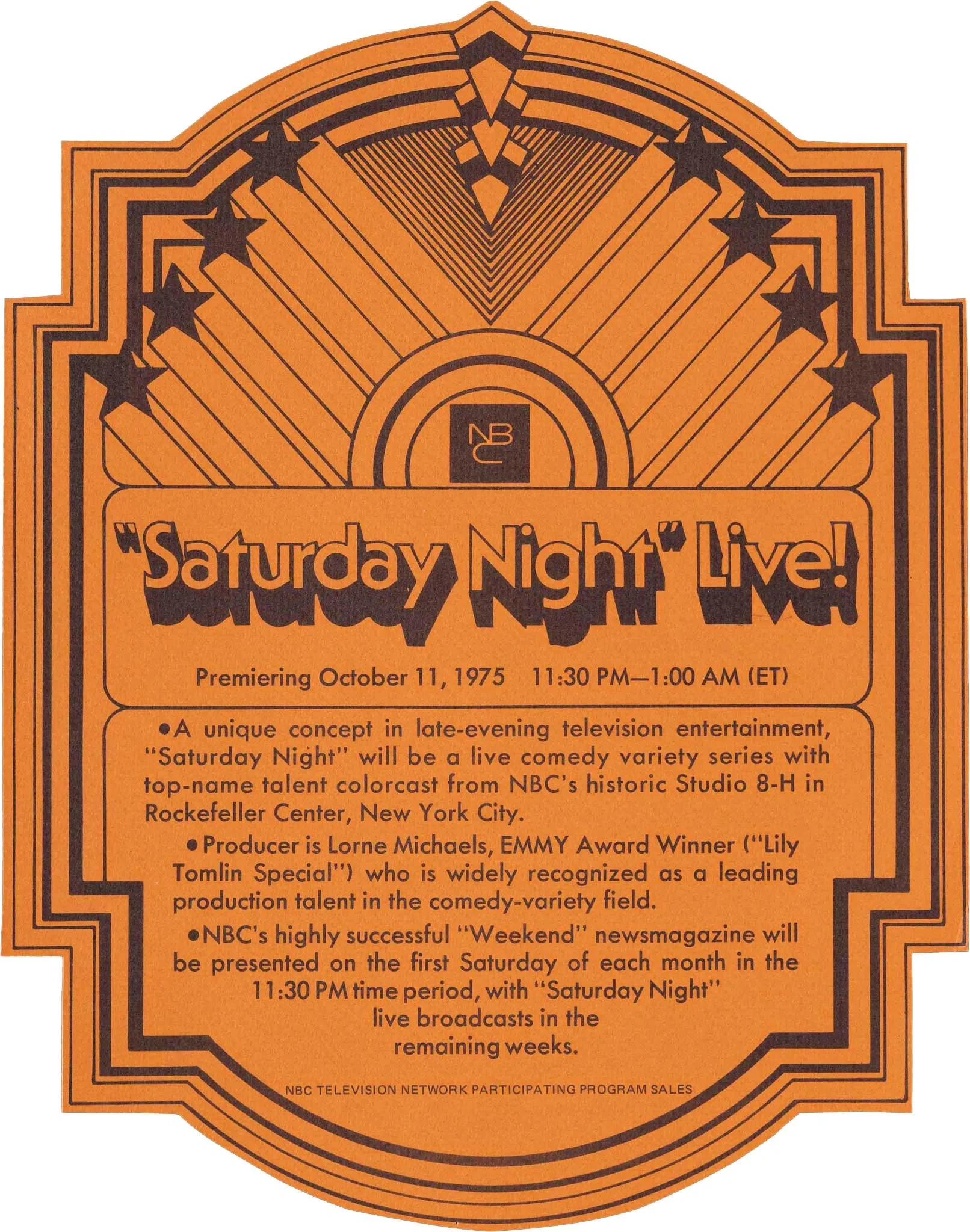

What was then called Saturday Night premiered on October 11, 1975, and Wilson was among a very small number of students who caught the episode on that Jester television. He particularly remembers being both baffled and amused by Andy Kaufman’s performance lip-synching the Mighty Mouse theme. That first show also featured host George Carlin and what would become the program’s first of many recurring characters, the absurdist “Killer Bees,” played by John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd, and Garrett Morris. Word began to spread, with more and more people around campus finding their way into that room.

“Every week the crowd would get bigger, until there were probably two to three hundred people around this one television set, watching Saturday Night Live,” Wilson says.

Almost 50 years later, Wilson got to tell that story to Lorne Michaels himself. In January, the 80-year-old Saturday Night Live creator announced he was donating his archives to the Harry Ransom Center. That’s where Wilson worked for more than 30 years, eventually becoming the Center’s curator of film. He retired in 2024 but recently returned to guest-curate Live from New York: The Lorne Michaels Collection, a public exhibit drawing on the trove of more than 700 boxes filled with papers, photos, tapes, and digital material documenting Michaels’ prolific career. It opens on September 20—even as a team of Ransom archivists will still be in the process of cataloging the collection. The full archive will become available in January.

The Lorne Michaels Collection is a big get for the Ransom Center, both literally—in size and scope—and given Michaels’ import. And while the Ransom Center often seeks out or competes for major archives (and can write a check to land one), neither was the case with Michaels. “They initiated this conversation,” Ransom Center director Stephen Enniss says. “We were absolutely delighted.”

Representatives from Michaels’ company, Broadway Video, first reached out to Enniss in 2022. Then, in January of 2023, a scouting party came to Austin, to learn firsthand about “the many ways we could serve Lorne Michaels’ legacy by caring for this archive,” Enniss says. “And it just fell into place very smoothly.”

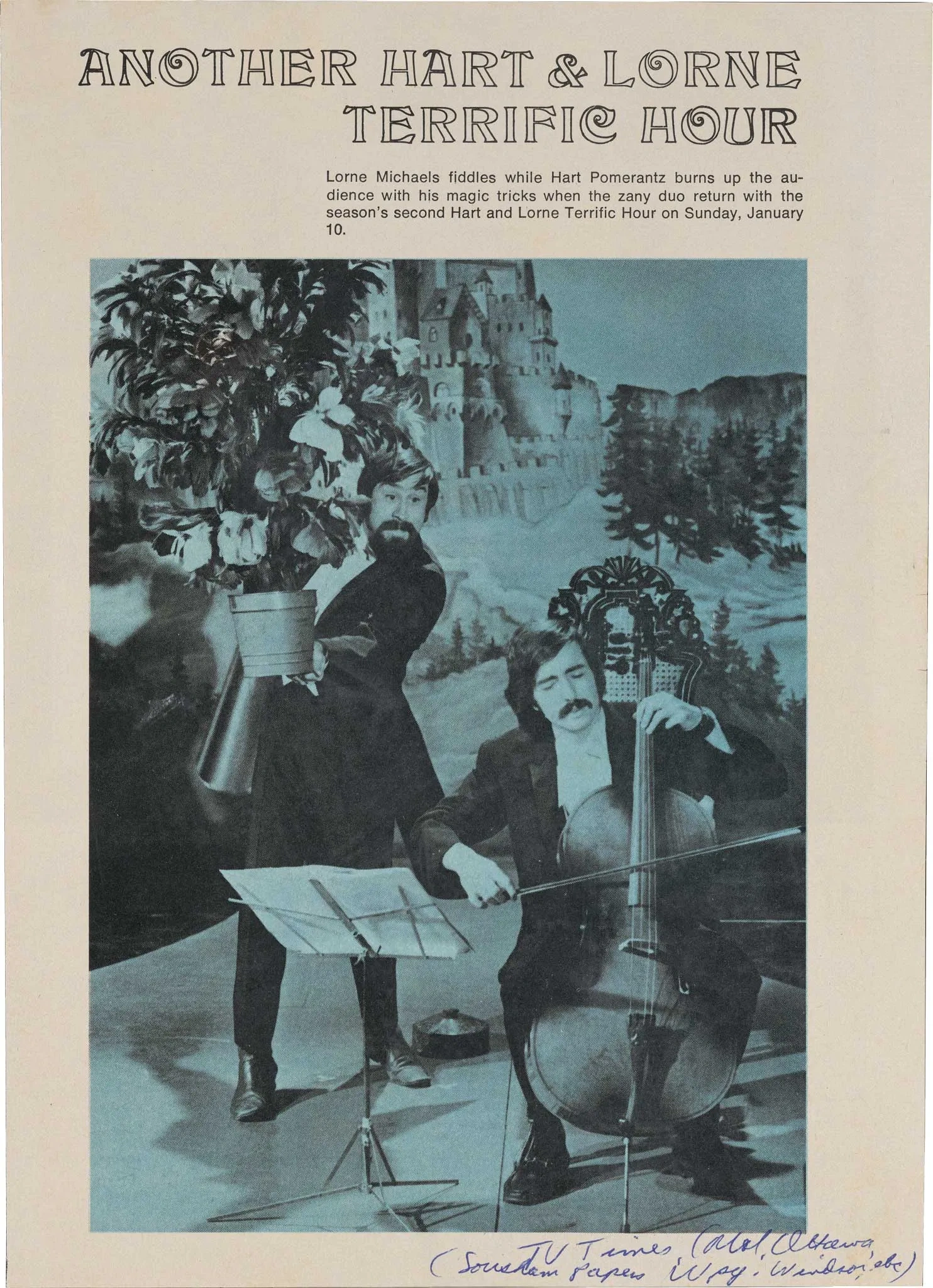

The collection is not just a Saturday Night Live archive, but an archive of Lorne Michaels’ entire career. There’s his early life, including summer camp theatrical productions; his formative but ultimately unsatisfying time writing for Phyllis Diller and Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In; and the Canadian variety show The Hart and Lorne Terrific Hour, for which he both wrote and co-starred. Michaels’ influence is also as much a part of cinematic history as TV history: The Blues Brothers. Tommy Boy. Wayne’s World. The many Will Ferrell, Adam Sandler, and Kristen Wiig films. His creative family tree also includes 30 Rock, Kids in the Hall, and Portlandia; more recent TV cult favorites such as Shrill, Detroiters, and Los Espookys; and both of NBC’s most hallowed talk shows: He has been the producer of Late Night dating back to Conan O’Brien, and The Tonight Show since it’s been hosted by Jimmy Fallon.

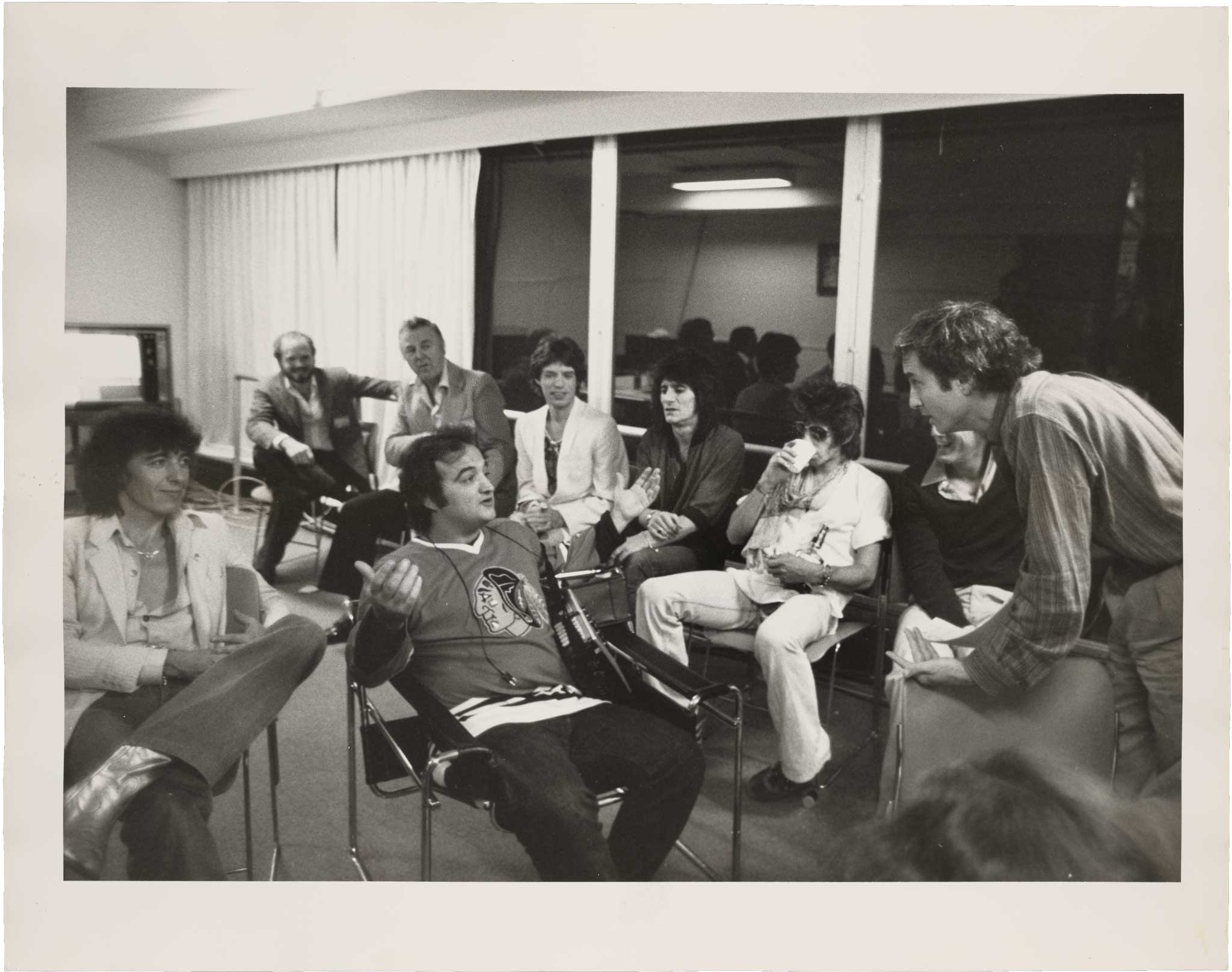

Then there’s all the music. From the many guests on SNL to Simon and Garfunkel’s “Concert in Central Park,” which Michaels produced, and The Lonely Island music videos “Lazy Sunday” and “D--k in a Box,” which began on SNL but went on to viral infamy.

The archives offer ample evidence of Michaels, the creative innovator; Michaels, the day-to-day producer; and Michaels, the mentor to a huge range of comedic talent. But its themes are also broader. “He’s had an outsized influence on comedy, and the culture in general,” Wilson says. “He wasn’t just trying to produce a funny show. He was commenting on what’s going on in the world and helping us understand our place in it.”

The Ransom Center was eager to announce the gift immediately but had to wait until after the show’s 50th anniversary celebration got underway earlier this year. When the news officially broke in a January New York Times exclusive, some wondered why the Manhattan-based creator of a Manhattan-based show with the tagline “Live from New York…” would send his life’s work to … Texas?

But the Ransom Center’s reputation speaks for itself. “We are one of the finest primary source archives and museums in the country,” Enniss says, without a hint of boasting.

Such literary figures as Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez may be the first names people associate with the Ransom Center, but it is also home to the archives of producer David O. Selznick, screenwriter Ernest Lehmann, and, in more recent years, Robert De Niro and Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner. All congenial company for Michaels, as Enniss puts it. Plus, he notes, Michaels was a big believer in the fact that SNL was for all 50 states, not just a New York City show.

“While we are, of course, here in Austin on the campus of The University of Texas, our reach truly is national and international,” Enniss says. “Any given day, there are researchers in our reading room from all around the country and all around the world. We have the capacity to bring the Michaels Collection alive for audiences not just here in Austin, but nationally and abroad as well.”

According to Wilson, Michaels was advised by someone—Wilson thinks it was author Joseph Heller—early in his life to start an archive. “He was just keeping things that he thought were important or things that he thought were cool,” Wilson says. “He did a good job in general. And he hired an archivist, thank goodness. That turned out to be really valuable.”

In other words, it wasn’t just a bunch of disorganized stuff in shoeboxes and tote bags. And the retirement of said archivist, Candace Bothwell, was a big reason why the Ransom Center came into the picture. Bothwell played a key role in the handoff to the Ransom Center team—including Jenny Romero, Wilson’s successor as curator of film, a position which was endowed in honor of De Niro in 2022, and project manager Ancelyn Krivak, MSIS ’07, who has been an archivist at the Ransom Center since 2008. Krivak first became aware of SNL from her father, who used to do the “Land Shark” bit when he’d knock on her bedroom door to wake her up for school. (Yes, all cutting-edge comedy eventually becomes Dad jokes.) Her own era was the ’80s, and Mike Myers’ “Sprockets” was her favorite recurring sketch.

The Ransom Center’s Lorne Michaels Collection team also includes project archivists Amy Griffin, MSIS ’23, and Neal Baker, MSIS ’23, plus project archival assistant Haden Edmonds, BS, BSA ’19, MA ’21. What they had to tackle was by no means the biggest archive—about the same size as Norman Mailer—but not as big as Selznick or De Niro, whose archive also includes more things that take up space, such as costumes and 35mm prints. As with De Niro, the archive also isn’t complete. New archival material will continue to come in for as long as Michaels produces shows. NBC also donated digital copies of every episode of SNL from all 50 seasons and will continue to do so as season 51 begins this fall.

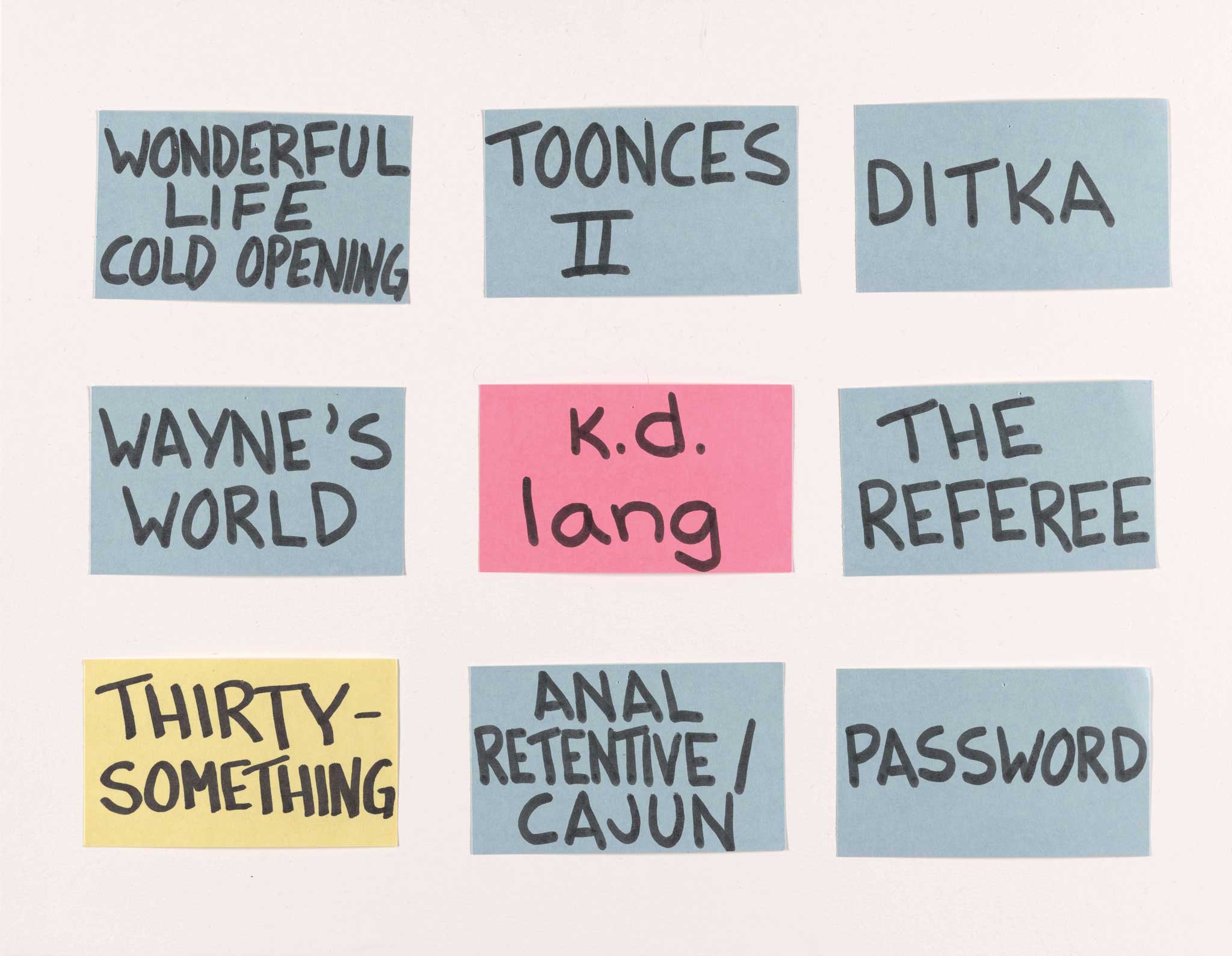

Krivak says the collection becomes noticeably less paper-heavy as SNL moved into the 21st century, but Michaels himself never became a fully digital creature. The show’s creation continued to involve things like handwritten cue cards, charts on walls, and notes on hard copies of scripts.

In addition to the extensive evidence of the show’s casting and production process, there are countless photos, both behind-the-scenes and from the show. There are also quirky, colorful documents, such as instructions for Michaels’ assistants, including that there should be a fresh bowl of popcorn on his desk (he is famous for this snacking habit).

One can imagine the Lorne Michaels Collection serving as a magnet for other people in Michaels’ orbit: just as the Ransom Center has not only Tennessee Williams’ papers, but material from Williams’ mother, his agent Audrey Wood, and friends such as Paul Bowles and Carson McCullers. It would make sense for Jimmy Fallon or Tina Fey—who worked with Michaels not only on SNL and 30 Rock, but also Mean Girls—to get their own archives down to Texas someday.

“There’s a kind of creative DNA that runs through these collections,” Enniss says. “When we acquire collections that are interconnected or have a relationship to one another, it creates a very fertile resource for further study.”

The Ransom Center is not the first place on the UT campus with a Saturday Night Live collection—though Cindy McCreery’s is a bit more modest. Visitors to the office of screenwriter and radio-television-film professor and department chair Cindy McCreery will find SNL memorabilia including a framed album cover of Live From New York by Gilda Radner and a set of Blues Brothers dolls. When McCreery first got word about the acquisition, she told her husband she had just received the most thrilling news since she started teaching at UT in 2011.

McCreery was born in 1975, the same year that the show premiered, so her firsthand memories don’t really begin until the Wayne’s World and Will Ferrell “cheerleaders” era. But, much like Krivak, the show’s early bits and characters trickled down from her parents and five elder siblings. McCreery was a Conehead on multiple Halloweens, though her favorite SNL characters of all time are Lisa Loopner and Judy Miller, the little girl who hosted a fictional TV show from her bedroom. Both were played by Radner.

“Gilda Radner has been my hero my whole life, so I’ve just always been a super fan,” McCreery says. “Saturday Night Live is really the reason I wanted to be a writer.”

And now, thanks to the Lorne Michaels Collection, she can use the show to teach new writers. Last year nearly 6,000 students visited the Ransom Center as part of a class. The Center even employs an instructional coordinator to facilitate collaboration between its curators and UT professors.

But you don’t need a UT affiliation to access the archives. The Ransom Center is known for its public-facing approach, offering open exhibitions, a reading room for all, and a screening room where visitors can view audition tapes and episodes.

“We’re not a warehouse,” Wilson says. “We don’t bring in these archives and put them on a shelf and wait for somebody to figure out that we have them. And very often, that’s important to donors as well.”

Every year McCreery teaches a graduate-level writers’ room class, which replicates the making of a TV show. This spring, the class will focus on sketch comedy, drawing from SNL and the Michaels Collection. Students will pitch and write their own sketches while also studying Michaels’ process. They’ll figure out what works and what doesn’t, how to accept and respond to notes, the value of thinking on their feet and revising scripts on the fly. And then they’ll team up with a multi-camera production class to actually make a show.

Michaels, in his role as showrunner and executive producer at SNL, notably made writers of his improv performers, and made the writers be producers of their own material—a revolutionary practice at the time. “So the writer would not only write the joke,” Wilson says, “but would have to talk to the costume designer about what this character would be wearing, and the set designer about the environment they’re in, and would produce that sketch through the performance.”

Presumably a big part of McCreery’s writers’ room will also be reacting to current events, just as SNL does. In that regard, the Lorne Michaels Collection has utility far beyond any one class or department.

“One of the things that I think is going to be most important about this collection is the way it serves as a lens for future students to look at social and political developments of the past 50 years,” Enniss says, adding that the Ransom’s collection of 19th century vaudeville, for instance, serves a similar purpose.

SNL was always commenting on and reflecting the news, and sometimes also made it—most notably Sinead O’Connor’s infamous and entirely unscripted performance of Bob Marley’s “War,” after which she ripped up a picture of Pope John Paul II. Watching the 50th anniversary specials this past winter, McCreery was struck by the series’ power as a time capsule, how it showed us presidents and presidential elections, wars, 9/11, and other world crises—both the good and the bad in the world. “It’s really a history of our country, too,” she says.