Good Reads Q & A: A Graphic Biography Introduces Old and New Readers to Jane Austen

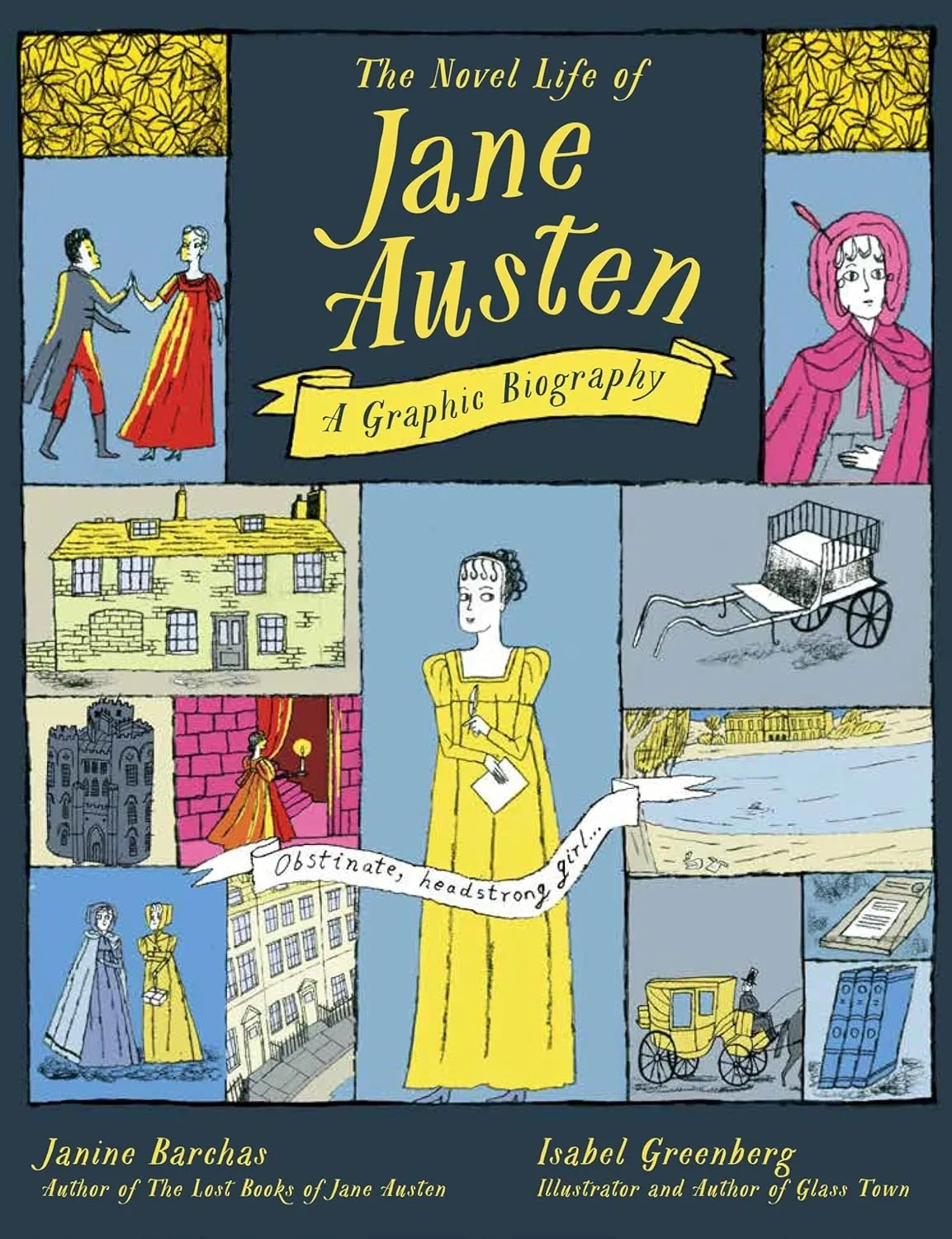

Janine Barchas joined The University of Texas in 2002 and holds the Chancellor’s Council Centennial Professorship in the Book Arts. Since then, she’s written three books (and counting) on Jane Austen, and even curated an “Austen in Austin” exhibition at UT’s Harry Ransom Center in 2019. She now brings her deep research background to a new format, accessible not only for the most passionate Janeites (a nickname for Austen fans) but for Longhorns of all ages. The playful illustrations transition between cool pastels for the biographical material and vibrant reds and pinks for scenes from Austen’s oeuvre.

In honor of what would be Austen’s 250th birthday this fall, the Alcalde spoke with Barchas about her most recent project, The Novel Life of Jane Austen.

Where did your interest in Austen originate?

I’m a reluctant Janeite. When I was asked to teach Austen for the first time, many years ago, I said, “Absolutely not.” Austen’s got Hollywood working for her; she doesn’t need me. The books that really need me are the ones that don’t have movies and mugs and T-shirts that say, “I heart Darcy.” Samuel Richardson and Sarah Fielding and Frances Burney: Those are the people I’m going to teach.

But eventually I was worn down, and it was in the rereading of the books for that class that I got hooked … And for many years now, I’ve thought Austen will jump the shark tomorrow, and it’ll all be over. But I’m working on my fourth book that has Austen at the center, and I just can’t believe that her stocks are still so high—and rising.

Did you ever imagine you would write a graphic novel?

An agent reached out to me [asking if I would be interested in writing a graphic novel about Austen.] I think it had to happen that way because I don’t think that I would have had the gumption to dream up a project where I’m only half the equation … But my answer to her was, “Obviously.”

I started rereading Austen’s letters and the novels thinking that I would pull out all of the quotations that might then make her own life story be articulated. I always had this sense of stealing, of the project being just one theft after another from Austen herself.

In the beginning I thought I would research new areas and new stories [to put in the book], and then I realized that it was much more important to show the reality of Austen’s daily life, the mundane domesticity of it, her sense of humor, her relentless optimism—not another love story, but the romance between the two Austen sisters, that love and mutual support.

The choice to have a very muted color palette for most of the book, but to have the panels pop whenever Austen starts imagining her stories—once we had settled on that, it was clear that the focus could be on the ordinariness of her life.

What did your creative partnership look like with illustrator Isabel Greenberg?

I wrote a script, of which [Greenberg] was the visual director. She would often come back to me with an idea for a scene, and I would tweak the language because the few words she’d added were not exactly [of the] Regency [era].

I built a visual library of Regency objects: what storefronts looked like, what a funeral looked like at the time. She very judiciously used all of the things I sent her … There were a lot of site visits, some of which we did together. We went to Chawton, England, together to take pictures of the cottage [where Austen lived the last eight years of her life and wrote her six novels]. It was about building a visual library for the artist to use to which only a researcher would have access—midwifing her imagination with those images.

What was your experience going from academic writing to crafting dialogue?

I don’t think it’s that great a leap when you’ve been trained by Austen herself … I’ve been reading Austen for the last 15 years rather closely and writing multiple books and teaching multiple classes [on her]. And as a child [growing up in the Netherlands], I spent all my pocket money on Dutch graphic novels … There are graphic novels now about genuinely serious, complicated subjects on which intelligent people can disagree. It’s a genre that’s very much alive, that wants to insert itself into ongoing conversations.

This is not a children’s book, though I think it can be a way of introducing a young person to Jane Austen … My ambition for the book is ages 8 to 80. My 85-year-old mother is reading it now in Dutch.

What is your favorite Austen work?

That depends on what I’m teaching that day, whatever novel I happen to be lecturing about. My enthusiasm is always real, and that’s my favorite on that day.

Do you have a favorite Austen character?

As I tell my students, I’m not interested in my own love for her characters; I’m more interested in Austen’s affections for her characters and which characters she gives which quirks.

I don’t have a favorite, but if pressed, I like Austen’s villains best in terms of what she does with them. Somebody like Mary Crawford, for example, in Mansfield Park and Caroline Bingley [in Pride and Prejudice] are well-psychologized characters whom I love to hate.

This interview has been edited and condensed.