A Longhorn Looks Back on 50 Years of Marriage

We met in 1965 at Midland High School, but we weren’t high school sweethearts. In fact, we didn’t even like each other. I thought he was arrogant and snobbish. He thought I wasn’t very smart. He finally realized his big mistake when he was in the school counselor’s office and saw a grid of SAT scores. Mine were—ahem!—higher than his.

Our first date was in the summer of 1968, arranged by a girl we both knew who realized we didn’t like each other. She and her boyfriend drove us to the white sandhills close to Monahans.

“She wanted to break up with her boyfriend,” my now-husband always says. “She had the hots for me and thought you and I would have a terrible time together.”

She bet wrong. We got along wonderfully, talking and laughing and kissing for hours that night.

After dating, then living together, we got married four years later. It was December 1972—a tumultuous month, when Richard Nixon was president; the Vietnam War raged; commercial flight crashes killed scores of passengers and crews in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Norway, and the Everglades; and Harry Truman, the country’s 33rd president, died in Kansas City.

But, at our small wedding at my parents’ house in Midland, we hardly noticed. Outside, the sun was blinding, and the wind blew, since the wind always blows in West Texas. In the photos, I am smiling broadly. I might have been terrified of flying, but marriage didn’t scare me at all. My husband, an intrepid flyer, looks nervous—like he appreciated the dramatic step we were taking.

We had so much in common and so much fun together, but we were also very different.

I was 23, gawky and painfully shy. An emotionally volatile childhood had left me fearful of the world. My husband, three months younger, was 22. From a more prominent family, he’d grown up a Tom Sawyer character, shooting off bottle rockets and accidentally setting fires now and then. My parents were happy at the match, but his thought he could have done better.

He was the smartest, funniest, and most creative guy I’d ever met. For most of my young life, I’d secretly thought I was smart and interesting—but he was the first person to ever notice.

What can I tell you about 50 years of marriage? We’ve earned advanced degrees, changed careers, been so broke we sold our wedding silver, been comfortable, had two children and four grandchildren, moved from Austin to Virginia to Dallas and back to Austin, laughed, screamed, weathered cancer, succeeded professionally, failed professionally, loved each other, delighted each other, disappointed each other.

Most of all, I can tell you about some of the most vivid, significant moments of our years together. It’s not a monolith; it’s a mosaic. The pieces are jagged, but so is life.

1973–77

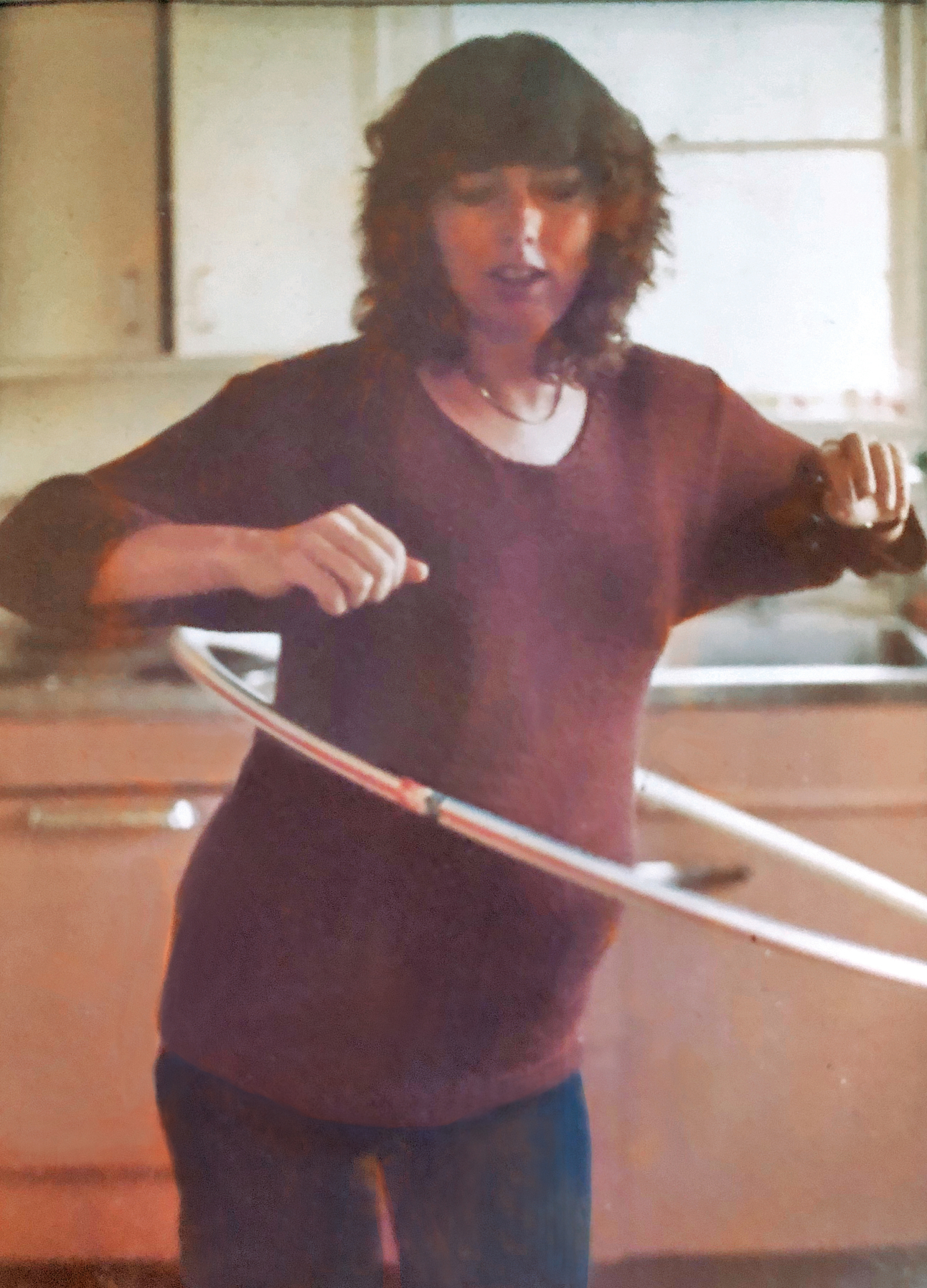

I go to law school, and my husband goes to graduate school in psychology, both at The University of Texas at Austin. In many ways, we are in different worlds. When we go to law school parties, eager students surround faculty members in three-piece suits and laugh loudly at their jokes; everybody’s posture is excellent. At psych department gatherings, faculty—whom I must remember to call by their first names!—are sometimes stretched out on the floor, drinking beer.

In my second year of law school, a visiting firm throws a party for potential summer interns. A group of us, including my husband and me, circle around one of the firm partners. He quizzes one of us after another about our ambitions and our strong points. What can we offer?

When he comes to us, my husband says he’s a grad student in psychology and a law school spouse. The partner begins to crack jokes about psychologists, one rude remark after another about mind-reading.

“You know what?” my husband says, finally. “You’re right! I can read every thought in your head. I know everything about you.”

The partner pales; his eyes turn panicky. He abruptly walks away from the group, which promptly falls apart. I don’t get an offer from that firm, as it turns out.

Degrees in hand, we move to Charlottesville, Virginia, where my husband teaches at the University of Virginia, and I am an indexer for a legal publishing company. My husband loves his work. I hate the mind-crushing tedium of mine.

Every day, I scour The Washington Post and tell my husband that I think I can write. After hearing this remark one too many times, he suggests I write instead of talk. I hammer out an essay about taking the bar exam, which The Washington Post publishes. I quit my terrible job and become a writer. It’s not a smart move financially, but I’m much happier.

We have lots of friends and give big, raucous parties that last till sunrise. Our indoor plants keep dying, though. Eventually, we figure out party guests have been using our plants as ashtrays. We are great as party hosts, miserable at keeping innocent scheffleras alive.

Four years later, my husband doesn’t get tenure, and we move to Dallas. That’s a convoluted, painful story I won’t go into—a big failure early in his promising career. He takes a job at Southern Methodist University and ramps up his already overwhelming work schedule. Years later, I tell him I think this early failure contributed to his later success and maybe even made him a better person. He tells me I’m crazy.

’80s and ’90s

My husband had a wild and enjoyable childhood, so he’d been eager for us to have children. My early experiences were very different. I was the older daughter of a deeply depressed mother who once told me she regretted having children. Would I repeat my mother’s life if I had children? The thought terrified me.

As usual, though, my husband’s sunny confidence about life and the two of us convinces me. Sure, he is sometimes outlandishly certain of a happy outcome, but he is right more often than wrong. And he is right about our having children: It is the best and most rewarding choice we ever made in our lives together.

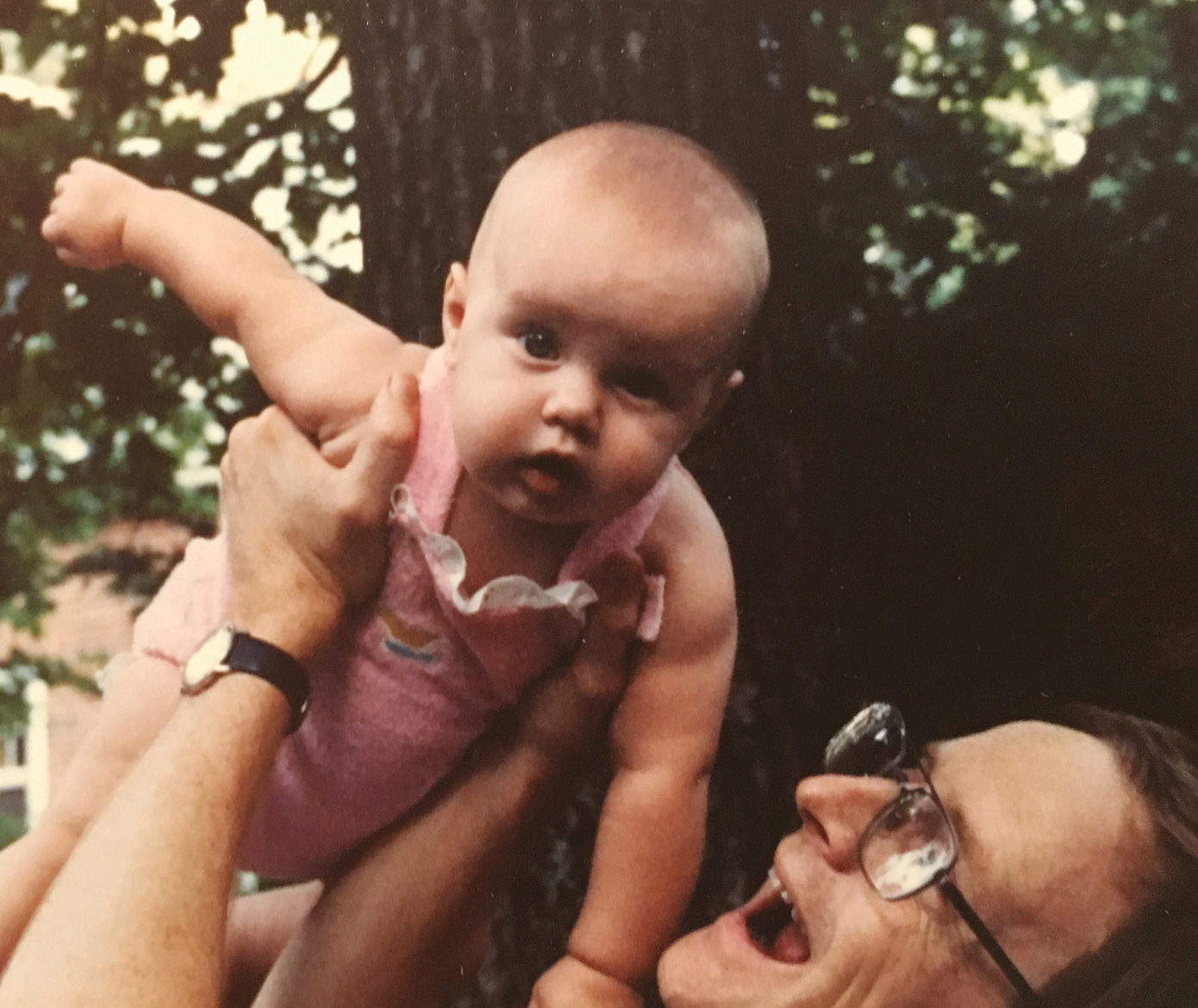

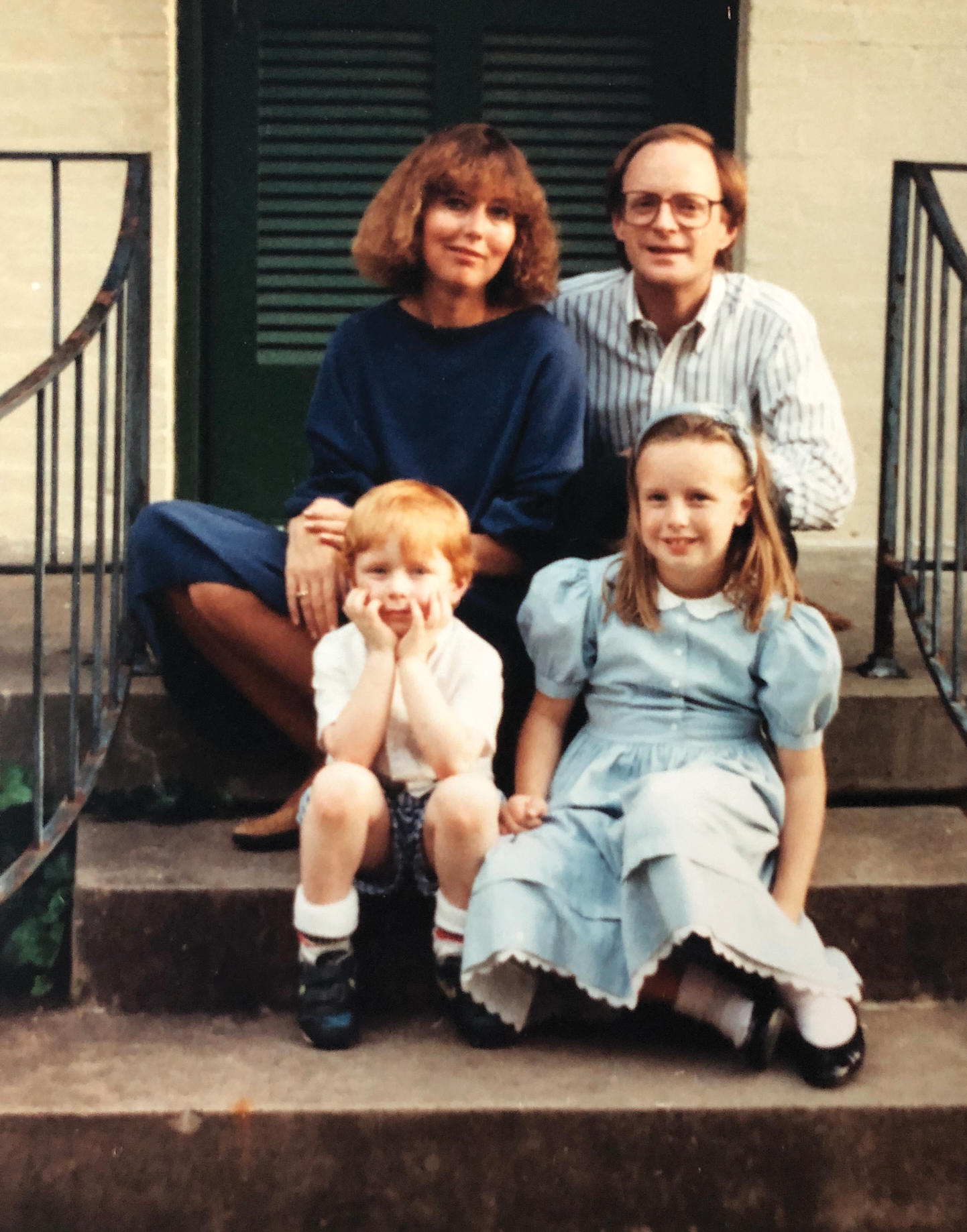

We have a daughter in 1982, a son in 1986. The frantic, chaotic years of too much work, too little time, toilet-training, cases of pink eye, loose teeth, and colliding ambitions begin. Aside from rearing children, we both work nonstop—me writing for newspapers, magazines, public television, and radio; him running increasingly renowned research on trauma and writing. I’m pretty sure we spend years without ever completing a sentence. Soggy Cheerios usually cling to the kitchen ceiling, and we regularly have to jump over major oatmeal spills on the floor.

Lest I forget to mention: Our children are wonderful—smart, mouthy, funny, sweet. A joy, I think now. But how do you have the time to appreciate that when you’re exhausted and overwhelmed by work and parenting obligations? When do you get to step back and savor it?

Rarely. If you had that much spare time, you’d rather sleep.

1995

I am at Baylor Hospital in Dallas, waiting for the pathology reports on my bilateral mastectomy to come back. I know the news is bad, since my surgeon doesn’t want to speak to me without my husband present.

My husband arrives. I tell him the news is probably terrible. The late afternoon sunlight slants into the room as we wait for the surgeon. We talk. We begin to put together a story: My surgeon is so depressed by my pathology report that he goes to a nearby bar. He gets so drunk, he vomits, then makes a pass at a waitress.

We are cooking now! We add detail after outrageous detail, trying to one-up each other: The waitress’ cowboy boyfriend punches the surgeon and knocks off his glasses. The poor surgeon, nearly blind and wretchedly drunk, is crawling around the barroom floor, trying to find his bifocals.

By the time the surgeon arrives, sober and grim-faced, my husband and I are aching from laughter, almost relaxed. The surgeon tells us the bad news of malignant nodes and upcoming chemotherapy and radiation. After he leaves, my husband strokes my hair and tells me we are going to make it through this. He is sure of it. We will be all right. I wonder how he knows that. But, as always, his confidence buoys me.

1997

Twenty-five years after we married and 20 years after we first left Austin, we move back. Everybody warns us that the city has changed for the worse—bigger, more bustling, losing its looseness and eccentricity. We move back anyway, and the volume and quantity of those remarks increase over the years. (Most recently, I hear that the good old days of Austin were definitely the ’90s.)

But people change as dramatically as cities do. My husband, who accepted a position in the UT psychology department, now travels the world talking about his research on writing and trauma and language analysis. I’m a newspaper columnist, young-adult novelist, and commentator for public radio.

We also seem to have become middle-aged. Our daughter begins high school, and our son, middle school. They think we’re old and slow-witted. (Since it takes us a good 20 years for us to figure out why our liquor supply was always so watered down, they may have had a point.)

My husband cooks dinners now, and I clean up after him. Maybe other people were Catherine the Great in their past lives, but I appear to have been a scullery maid. Our now-adolescent children complain about the meals and almost everything else we do. To rebel, our daughter becomes a vegetarian. That lasts about two months. She also joins the school debate team and starts to win all her arguments with us. That lasts roughly forever.

Our son babysits occasionally along with a neighborhood friend. Only much later do we find out the two sitters sometimes tied up their younger charges so they could learn to free themselves. “In case they ever get kidnapped,” our son explains later. “It’s great training.” I am horrified, but my husband thinks it’s hilarious. Fortunately, the children’s parents still laugh fondly about it.

The Early 2000s

Maybe you never realize how much you identify as a parent until your children begin to leave home. Our daughter leaves for college in the fall of 2000; our son, in 2004. My husband reports recurring dreams about a baby who has gone missing. I find myself irresistibly drawn to infants when I go to the grocery store. It takes us some time to realize we will always be parents—a family—even when our children have grown and moved away.

My husband becomes chair of the UT psychology department. I accept a position as a writer for the UT System and travel to campuses all over the state. For the first time in years, he and I are able to travel widely together. The empty nest turns out to have some great advantages.

2009–10

My husband takes a year-long sabbatical. We can go anywhere. We go to New York and live in a sublet on the Upper West Side. We both work part-time and enjoy ourselves full-time—at theaters, museums, restaurants, with friends. This is the year we both turn 60. It’s wonderful to take advantage of this opportunity and find out we can have one of our fullest, most enjoyable years later in our lives.

2011

We sell our house in Austin and move to a downtown condo.

2014

Our daughter marries a wonderful guy. She knows I lack the Martha Stewart gene, so she only dispatches me to the local Planned Parenthood office to pick up condoms for guests’ gift bags. This mother of the bride: no good at flowers and organization, but highly reliable when it comes to rubbers.

2017

My husband has surgery for prostate cancer. As I mentioned earlier, one of his major areas of research is how one’s emotional and physical health improve after talking or writing about trauma—so I try to encourage him to express himself. “I don’t need to talk,” he says, grumpily. I go around telling people that he studies emotions, while I have them.

2019

Our son marries a lovely, witty woman in Chicago in January. We cry; we dance; we toast to them. It’s warm and celebratory indoors and freezing cold outside. A polar vortex, they are calling it.

2020

Like everyone else, my husband and I go into lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s a lonely, uncertain time. I realize how fortunate I am to be with someone I still consider to be the most interesting person I’ve ever met in my life.

2015, 2017, 2020, 2021

We are delighted to welcome four grandchildren over these busy years.

Late 2022

We near two landmarks. On Dec. 30, we celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary with our family in New Orleans. Then, less than a month later, my husband retires. UT hosts a conference in his honor, with family, friends, former students, and colleagues traveling here from around the world.

In many ways, these two monumental events are overwhelming. We spend hours, just the two of us, talking about our lives together—the joyous times, the fraught and screaming times, the love, the fun, the fury. We married young, and we grew up together. Now, in our early 70s, we are growing old together.

“I know we’ve made each other better people,” I say one morning, and my husband agrees. Being with him has bolstered and steadied me, given me confidence, awakened me to new experiences; I know that I have ratcheted his heart open to reach out to others more, to try to understand their pain, to see a more vivid and complicated world around him. We have built a life together filled with a wonderful family and a host of friends. I will never love another person more. Even when we travel thousands of miles with each other, when I am with him, my heart is lighter, and I am home.

CREDITS: Illustration by Michael Marsicano; photos courtesy of Ruth Pennebaker; Matt Wright-Steel (above)