Kenny Vaccaro Is Taking on the World of Esports

Anyone who’s ever seen Kenny Vaccaro, ’12, has a Kenny Vaccaro highlight burned into their head. Perhaps it was one of his many crushing tackles covering punt returns. Or a sack, like when he fully leapfrogged over a hapless blocker to get to Cal’s Zach Maynard in the 2011 Holiday Bowl. Or maybe his interception—while wearing the number of injured teammate Fozzy Whittaker—of Texas A&M’s Ryan Tannehill in the last game of the rivalry (for now).

More recently, there was his all-around performance in the 2019 NFL playoffs. Vaccaro, who started his pro career with the New Orleans Saints, helped the Tennessee Titans shut down Tom Brady and the New England Patriots in a stunning wild card upset, 20-13, then contributed an interception and five tackles in an equally unexpected 28-12 win over the favored Baltimore Ravens. And if you happen to be from in or

around Vaccaro’s hometown of Brownwood, Texas, you probably remember not only the years of football that will soon put him into Brownwood High School’s Hall of Champions, but his younger days in almost any sport. The speedy and relentless—you might even say, all gas, no brakes—Vaccaro broke the Texas state record in the 400-meter dash when he was 10 years old, and also excelled in soccer. “I thought that might have been my avenue: pro soccer player,” Vaccaro says. “But the moment I picked up a football, everything changed.”

Now, everything has changed again. In 2022, Vaccaro’s highlight reels are something else entirely. In fact, he’s not even Kenny Vaccaro, but “Savage.” And instead of running around football fields and making vicious tackles, he’s running around virtual worlds and making vicious kills in the multiplayer first-person shooter games Destiny and Halo, while also streaming and “casting” (essentially, doing play-by-play) on Twitch.

Vaccaro was on the Texas team that last played in—but did not win—a national championship game (against Alabama in 2010). That 2019 Titans team led Kansas City at halftime of the AFC Championship Game, only to see the Chiefs go on to win the Super Bowl. He’s still hungry for a championship—perhaps complete with a parade in Austin—not in football, but in esports. And not as a player … but as the owner of a team. The 31-year-old is now the CEO and co-founder of Gamers First (“G1” for short), an Austin-based organization in its first official year on the professional gaming circuit.

Vaccaro has been a gamer almost his whole life, and a truly serious player on the esports scene since 2018. After being released by the Titans in March 2021 for salary cap reasons, he didn’t suit up for another team. On Dec. 1, 2021, he finally let the world know why—with a video on social media, of course.

The one-minute and 42-second clip Vaccaro posted to Instagram and Twitter was accompanied by just one word—“Transcend”—and showed him walking the field of DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium alone, in a G1 cap and T-shirt, the footage alternating with career highlights from both UT and the NFL followed by a dramatization of Vaccaro passing up a chance to return to football with the Atlanta Falcons. The final image is a helmet—not the familiar white and burnt-orange Longhorn, nor a Saints or Titans logo, but rather, the green helmet of Halo’s Master Chief.

While it wasn’t quite as elaborate as LeBron’s The Decision, this was Vaccaro’s way of saying, “I’m taking my talents to the gaming world.” His NFL career was over, and G1—after several years of planning, and existing in the background (including with a team in Destiny) was truly official. The company held a proper launch party in the spring of 2022, at the same time it also began competing in Halo.

Remember that moment in the movie Say Anything, when John Cusack’s character Lloyd Dobler explained his career plans to his girlfriend’s hostile father? “Kickboxing. Sport of the future,” he said. But 30-some years later, the new sport of the future is on computers, consoles, and your phone. Esports is booming in and of itself, with teams, tournaments, and leagues around the world in games such as Fortnite, Halo, and Call of Duty, including high school, college and pro. Esports has also quickly become part of the traditional sports world, not only with equivalent gaming spinoffs (NBA-supported teams that play NBA 2K, for instance) but with team owners and athletes—including the likes of Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones and Kevin Durant, ’07—becoming partners, sponsors or investors, and the action playing out not on cable television, but TikTok, Twitch, and Discord.

Just as mixed martial arts supplanted boxing (and added in some of the color of pro wrestling), esports means a lot more to young people than America’s former ubiquitous pastime, baseball (average TV viewer age: 57), and is no more or less relevant than the NFL and NBA—especially since NFL and NBA players, like Vaccaro himself, are also gamers.

In July, one long-established esports org, FaZe Clan, went public as a special purpose acquisition company with a $725-million valuation. Among its board members or investors are Snoop Dogg, the WWE’s Stephanie McMahon and Arizona Cardinals quarterback Kyle Murray. The perception of gaming as something for basement-dwelling computer nerds long-ago faded into history.

“I think gaming is like the fourth pillar,” Vaccaro says. “There’s sports, music, fashion. And now gaming.” Vaccaro and his wife, Kahli, have four kids. Vaccaro’s eldest son, 10-year-old KVIII, plays for his father on a national championship-winning flag football team.

But football still does not have the same hold on him, and even less of one on 7-year-old Kendon. “When I come home he’s watching streams on Twitch. He’s not watching football highlights anymore. And that’s how the youth is in general.”

The interest of sponsors and advertisers and media companies reflect that—and the gaming orgs are also media companies in and of themselves. G1 is a team first, one that recruits players, has the equivalent of a coach and general manager, and competes in a league. For Halo, that’s the Halo Championship Series (HCS), which is owned by a subsidiary of Microsoft (as is the game) and has its title tournament in October. Any team can play in it, but the Top 16 teams tend to be professional. But just as important to G1 and all other orgs is the branding, storytelling and content creation. Every gamer on the team is on his own hero’s journey, which Gamers First currently documents with a monthly YouTube show, Ascension (à la HBO’s NFL training camp behind-the-scenes Hard Knocks). The best ending to the story is still winning, but the twists and turns and personalities and online communities are also crucial. And fans eagerly spend their time and money not just on playing and watching, but on custom character “skins” and merch drops.

Gamers First is called that in part because the organization intends to put both the gamers who play for it and the gamers who follow it above all. But it’s also Vaccaro’s statement that he’s a gamer above all, and always was, before, during, and now after football. It’s even right there in his official UT bio, which goes back to his freshman year, 2009 (and can still be found online).

“Favorite actor: Will Smith.

Favorite CD: Tha Carter III by Lil Wayne

Favorite video game: Halo.”

Aleisa Vaccaro was not necessarily a fan of gaming.

Kenny Vaccaro’s mother wanted greatness for her son, and that meant discipline. Vaccaro was a dedicated athlete almost as soon as he could walk—that’s when the track and field and soccer started—but his mom was also strict about making sure he paid attention to school and homework. As Vaccaro remembers it, there was little time for friends and fun, with Aleisa working hard, and pushing her children—Kenny, his younger brother and eventual Longhorns teammate Kevin, BS ’16, and two younger twin sisters, Keeta and Ashley, to a better life. That goal became even more paramount when Aleisa became a single mother: Kenny’s father, Ken, died of emphysema when he was 16.

“It was all about my future, and her vision for me,” Vaccaro says. “And I resented her for a long time for it. But that made me who I am.”

Of course, a parent’s strictness can’t always keep a kid from gaming (and hey, there were certainly worse things he could’ve been doing), nor could they really keep the kids from having consoles. Vaccaro still remembers his first black-and-white Nintendo Game Boy, then later playing Donkey Kong and Super Mario Bros. in color. Then came the cell phones, with Snake and Brick Breaker. Then, of course, multiplayer shooters, back when that still meant going over to someone’s house, with four people on a split screen, each with their own controller: Halo, Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto. He and Kevin also played Runescape, one of the early MMOs (massively multiplayer online games), on their computer (and he still does, with the same account).

Perhaps his mother even realized what Vaccaro himself now understands: that gaming was more than just a frivolous pursuit. “It was therapy for me,” he says. “Growing up the way I did, not really having much … being hungry at times. Electricity getting cut off. Water getting cut off. Being able to game when I could was my escape. My getaway.”

Then and now, he gets the same thing from gaming that others people get from meditation or going on a hike. “You’re just in the moment, focused on the task at hand. And that gives you a certain mental peace and clarity,” Vaccaro says.“I put my headset on and I don’t think about anything. It’s always been my natural escape.”

Of course, football was its own escape. “I could take some of that anger and pain and passion and put it into a physical sport,” he says. There was also never any question which side of the ball Vaccaro would ultimately end up on. He always preferred—and had the mentality—to play defense. In every sport. In basketball, he’d foul out. In soccer, red cards. “Not because I’m dirty,” Vaccaro says. “But because I was just super, super aggressive. I love hitting. Defense is a different mindset. There’s a reason why certain people play it and certain people don’t. And I was always that guy.”

And while lots of schools recruited him—and his mother fantasized about him going to Stanford, or even an Ivy—he was probably always going to end up at UT ever since he watched the 2005 National Championship Game with his brother in their father’s trailer. As Vince Young scored the winning touchdown against USC on a pre-HD television (“one of those big box TVs where there’s like, wood on the outside”), he told his dad that he was going to go to Texas.

“From that moment on, I had a dream of going there. I never really played the game to go DI. I just played the game for my teammates and just the love of ball. But I had in my heart that I wanted to play for Texas. I wanted to play for the state I was born in.”

With his football path set, Vaccaro actually spent his senior year at a different high school, Ealy, where his season came to an end due to a torn ACL. That didn’t slow him down, however. He was fully rehabbed by his freshman year at UT, where he immediately became a terror on the kickoff coverage team. After a big hit or busting of the wedge, all the older starters would explode off the of the sidelines to congratulate him. Former Longhorns defensive backs coach and defensive coordinator Duane Akina, who coached under Mack Brown for more than a dozen seasons, says Vaccaro was as physical of a football player as he’s ever coached in his 40-year career, and someone who would have stormed the beach at Normandy.

“He was really an inspiration for us on how to take the field,” says Akina, who still shows Vaccaro highlights (as well as Quentin Jammer, ’01, and Quandre Diggs, BS ’14) on what he calls his “gold reel” for players at his current job.

If Vaccaro’s toughness and competitive spirit set him apart, Akina says he made himself a high first-round draft pick (#13) in UT’s 2012 game against West Virginia, where he consistently limited star wide receiver Tavon Austin (who went on to his own great pro career) in man coverage.

Getting to the NFL also got Vaccaro back to gaming, if not entirely by choice. During his rookie season with New Orleans, he broke his ankle, and with nothing else to do in between rehab and PT, he got addicted to Destiny. It all came rushing back. Not only his love of the game, but the fact that he loved it just much as football. “I just started getting the same feelings I did when I competed,” Vaccaro says. “The same type of rush and dopamine experience I’m getting when I make a play on third down.” This time, after returning to the field, gaming stayed in his life—perhaps to a fault, at times.

“I started streaming and gaming every day,” he says. “I would come home after a big game and I literally would stream all night. Sometimes six, seven, eight hours. My wife wasn’t happy about that.”

But once again, it was more than a frivolous pursuit.

Vaccaro’s “Savage” gamer tag is, of course, self-explanatory.

Vaccaro’s partners in G1, COO Hunter Swensson (“Makowski”) and creative director Cody Hendrix (“Haipur”) are both longtime gamers, while G1’s Halo team includes several veteran players with time in other organizations.

“The first time I played with Kenny it was exactly what I expected,” says Swensson, a professional Halo player since he was 19 who first got to know Vaccaro online, then teamed up with him to play Destiny trials together. Swensson is a Texan and ex-football player himself, so he had little doubt Vaccaro would belong. “The same kind of fire and passion I saw from him on the football field, I saw from him in the [games].”

A lot of athletes and sports franchises are involved in gaming. But often it’s just for show, or an awkward fit. For Vaccaro, Gamers First is not a side hustle or empty branding partnership. He’s in the trenches, but he had to prove that to the gaming world and his future partners first. When he started playing seriously in 2018 he went on what he refers to as The Respect Tour, putting himself out there, streaming and casting, taking on all comers. “The gaming community’s unique,” Vaccaro says. “You have to prove you’re legit. They don’t really want to get involved with just a token NFL player.”

What endeared Vaccaro to his future partners and players—his authenticity, rawness, and passion—are ones that any fan of his ball playing will recognize, and are qualities he hopes comes through in G1’s storytelling. It’s also the mentality he’s bringing to his new life as a businessman. Having been on the other side, Vaccaro says he’s focused on being a good owner who treats players well. Many of the G1 principals, including Vaccaro, were originally together at another org called SOAR, but they had issues—with how the players were treated, promises that weren’t kept, pay, a lack of attention to detail—and decided they could just do it better themselves.

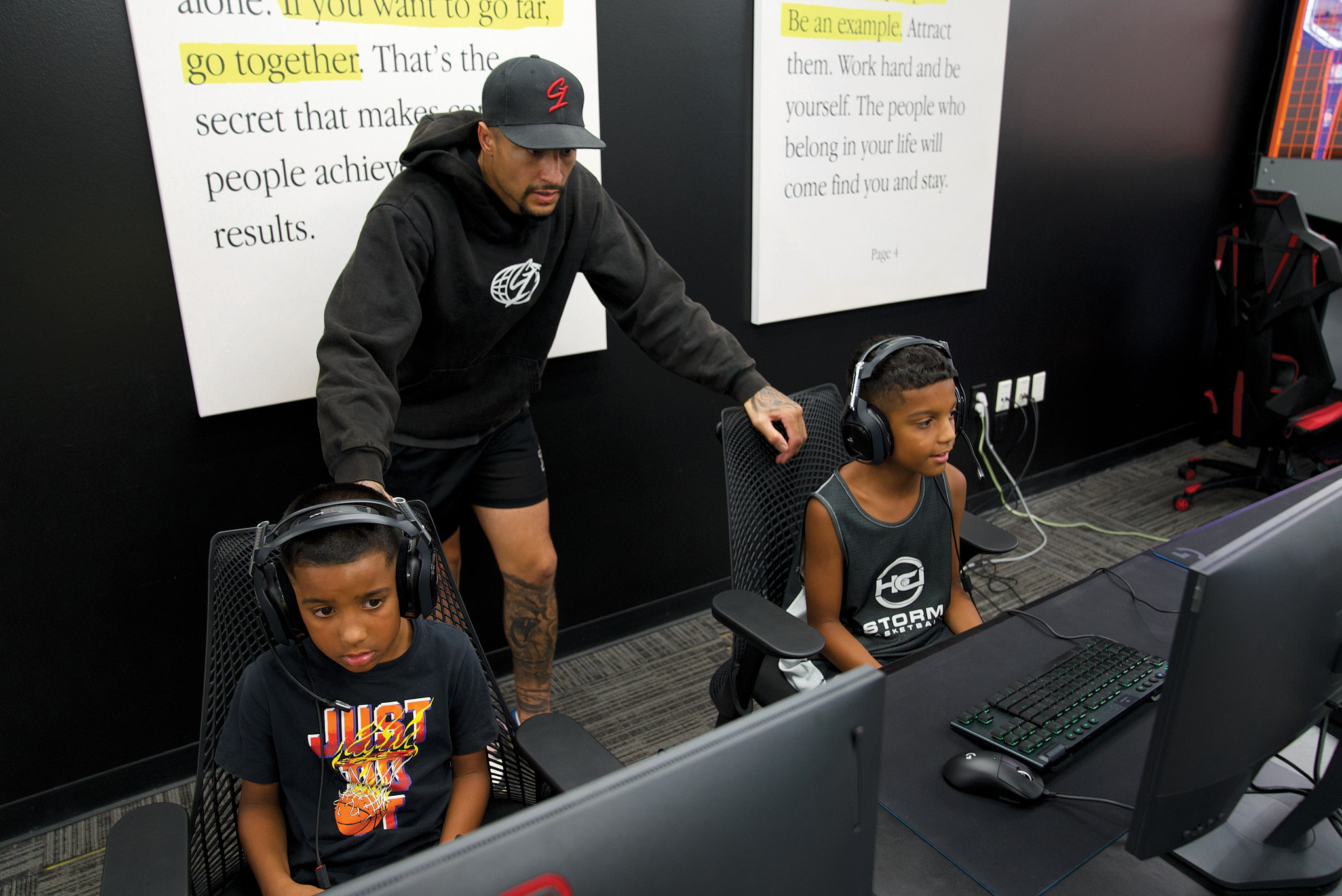

The Gamers First complex, a 30,000-square-foot facility in the heart of Austin’s South Congress ’hood in what used to be the Austin Opera House, is impressive in the same modern, expansive way that UT Athletics facilities are designed to dazzle. The space is not only packed with computers and gaming chairs for the teams, but also includes a full “social performance club” called Kollective (i.e. a gym) that’s open to members from the general public. There’s a fashion boutique, Konnect, with curated goods such as apparel and sneakers, G1 merch, and even original designs by Vaccaro under the name Kollective by Kenny. It’s all just another way to tap into the role gaming—and the styling around it—plays in the cultural zeitgeist. People may not realize it, says Vaccaro, but just like NFL or NBA players, “gamers are some of the biggest hypebeasts around.”

For the team, there’s an on-site physical therapist and a gaming-specific protocol for both physical and mental fitness—sleep, nutrition, working out, and general mental health. There’s also coaching from former player Eli Hensley, aka “Eli The Ninja,” complete with analytics and strategy and game plans. Just like in football, where you learn to know which way a receiver is going to go based on how he moves his hips, in Halo you practice studying a sniper’s tendencies.

Promoting good mental health, and destigmatizing the discussion of it, is a priority to Vaccaro. He sees today’s kids dealing with even more than he did: struggling with self-confidence and expectations raised by social media. And gamers are no exception, often measuring their self-worth by their viewership counts. “Guys like me that have a platform, I feel like it’s my job to speak up on it and be vulnerable, because that’s going to help somebody, right?” he says. And he has a unique perspective to share that’s somewhat counterintuitive to the common criticisms around kids gaming: His own childhood sense of it as a meditative tool against anxiety and depression. “It could honestly be in treatment facilities for people that are dealing with certain things,” he says. “Video gaming takes your mind off all the pain.”

As for Vaccaro’s Halo team, they have yet to win a tournament, but are doing well for ... an expansion team, if you will. In May, they won the Halo Championship Series Kansas City 2022 “Astro Breakout Team Award,” and they’re gearing up for the end of the season this fall, where a good performance in Orlando would allow them to qualify for the world championship in Seattle. “Our team is already miles and miles ahead of a lot of people,” Vaccaro says, “and it just got started seven months ago.”

That sense of camaraderie may be part of what eased the transition off of the field for Vaccaro, who says he doesn’t miss football. “For me, it was more about the relationships,” he says. “The locker room talks and the camaraderie, the teammates that I truly loved off the field—when I played next to them, my performance was better. And their performance is better. I’m doing it for them. I’m not doing it for anybody else, right? It’s a feeling that not everybody gets to experience.”

And now he wants his esports team to have that same experience—that sense of telepathy, of being able to read a teammate’s mind, and knowing how they are going to play. In football or in esports, it’s a bond that comes certainly from communication and practice, but also from friendship, which Vaccaro is committed to fostering.

And of course, a love of the game helps. “I love competing,” he says. “I would do anything right now to win a Halo World Championship. I didn’t get to win a Super Bowl ring, but shoot: I’m going to hoist up a Halo trophy one day.”

Akina doesn’t doubt that. “So many football players when they’re done, they’re lost,” he says. “Kenny’s such a passionate individual. If he’s in, he’s all in, whatever he does.”

CREDITS: Portraits by Matt Wright-Steel, UT Athletics, Joseph Johnson