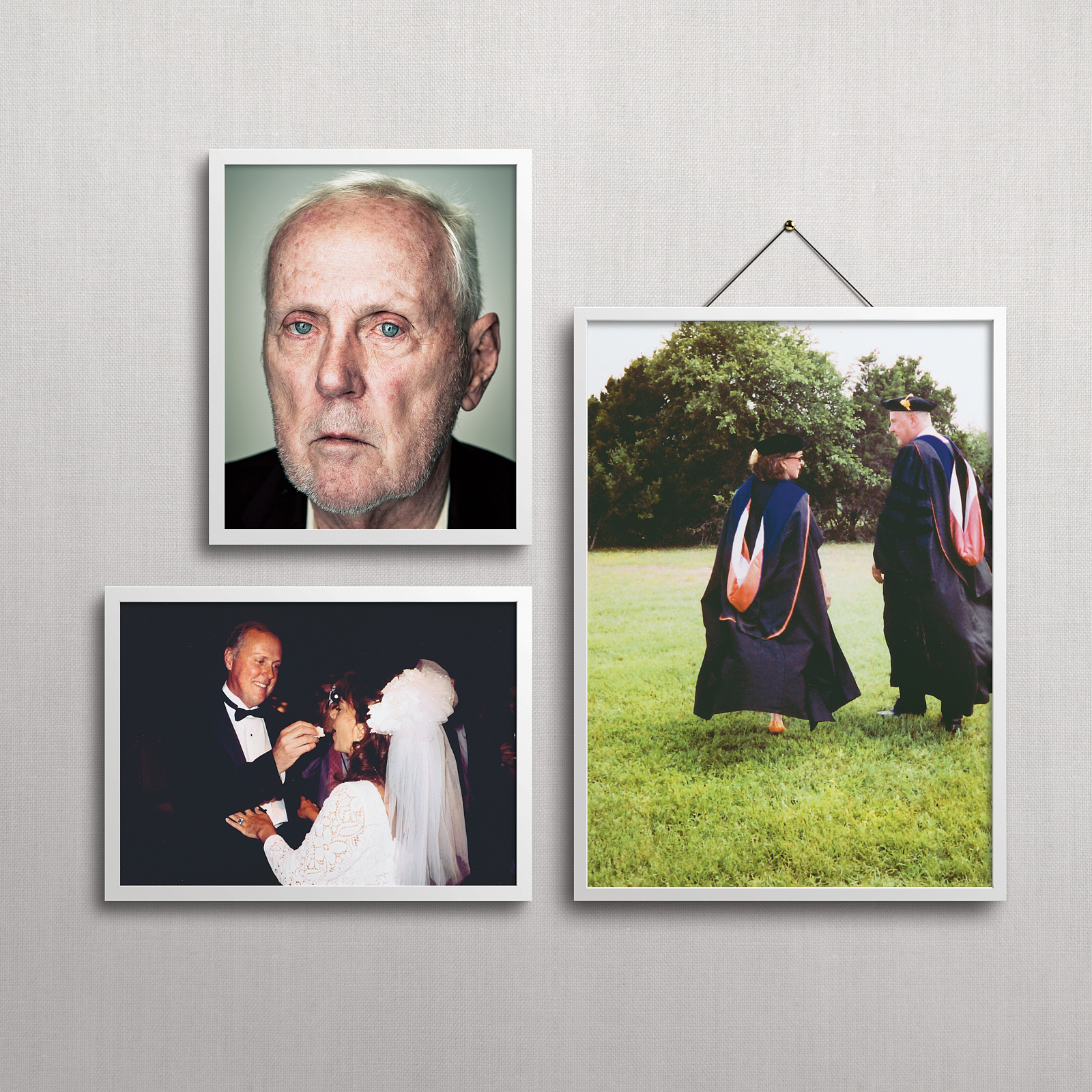

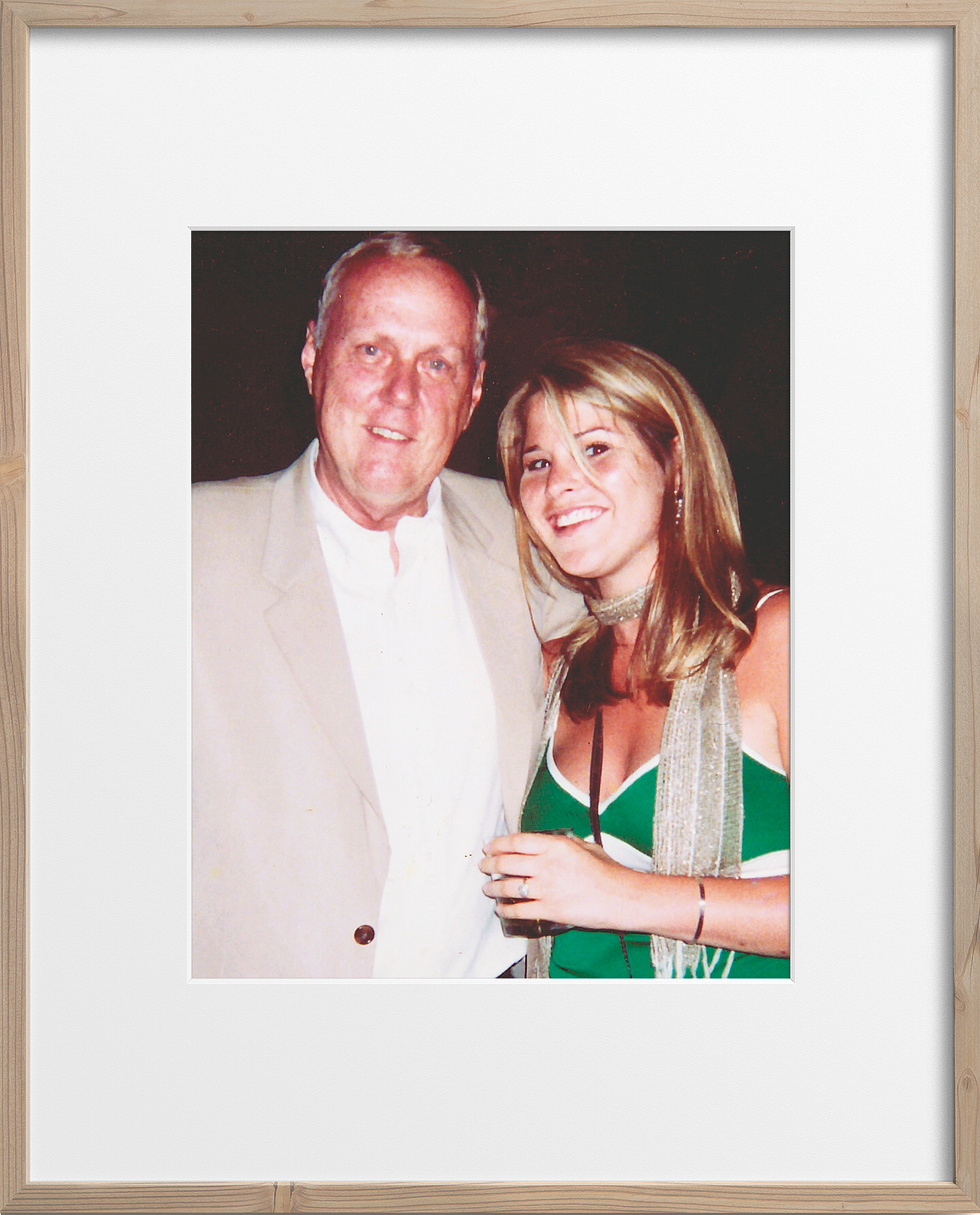

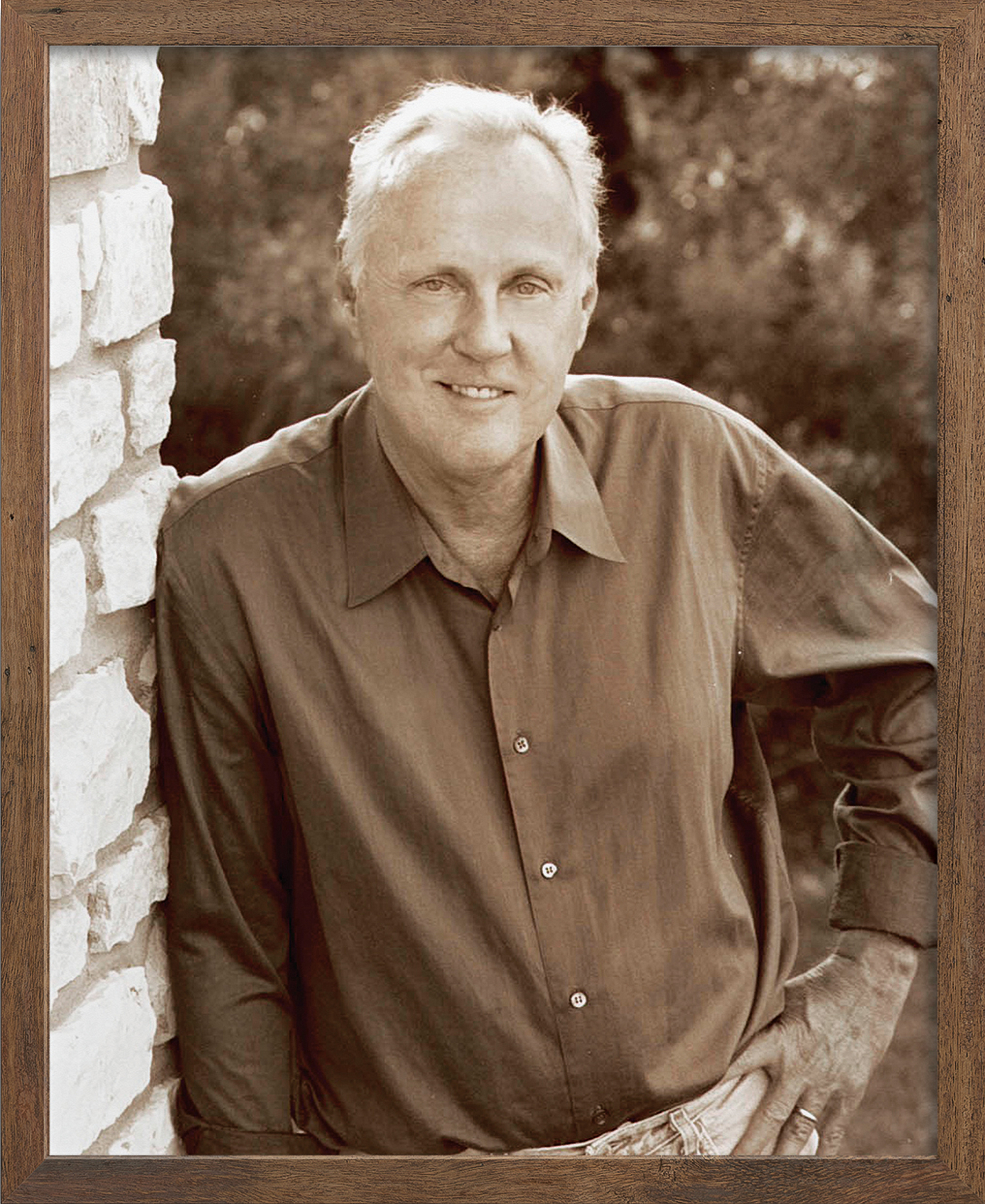

After Life: Remembering Don Graham

Don Graham took his last breath on Saturday, June 22, 2019, at 6:33 a.m., as I held his hand in mine in a narrow room at St. David’s Hospital in Austin. It had been a long time since I had seen a sunrise, and the gray outside his window was beginning to infuse itself with rose and gold. It was his last roundup, as he would have called it, and I pray he went as peacefully as he could, his lids closed over eyes as blue as the Caribbean. Unlike me, Don was an early riser, so he would have appreciated the timing. It was the horrible denouement of his glorious and productive life, and an abrupt new start to my own.

A cheery nurse came in to ask me if I thought Don might benefit from a water-soaked sponge in his mouth, like a lollipop, since he could neither eat nor drink. “He’s gone,” I said. She was embarrassed. “They hadn’t put a note on the door,” she responded. “He died seconds ago,” I told her. “Died” is a singly syllabic word that can become a tongue twister, and I listened to myself twist it.

Above all, Don was a man of words, and a man of his word. His last to me were typical morning words, at home and always welcome, words that I had taken for granted for so many years. “Here’s your coffee, sweetie,” he said, setting down a steaming cup on my bedside table. He, too, had probably taken my words for granted, knowing what they would be. “Love you, sweetie,” I said. “I think I’m going to try to sleep for a while longer.” I sleep well, especially in the morning, and so not drifting back immediately was unusual.

But on that morning, I lay there and listened to the comforting sound of running water from the kitchen. Don was washing dishes from the night before. From bed I could visualize him at the sink. I heard dishes clattering, followed by an eerie silence. I figured he had gone into his home office to begin writing; we had done this same routine thousands of times. When I would greet him in his office, he would ask me if I’d seen the empty sink. “See what I did before you got up?” he’d say, and I would respond, “Now, that’s love.” Those were the words we would have said to each other that morning.

Instead, I found him on the kitchen floor, eyes wide and beseeching. Don was rarely uncertain or confused. Why was he sitting like a rag doll, legs spread slightly, his back to the dishwasher? What’s happened? he telegraphed, and then, help me. He tried in vain to stand up, his left side already showing the signs of paralysis by stroke (on the right side of his brain, which controlled memory and reason and all the other brain activities Don lived by). “You’re scaring me!” I shouted, as I tried to help him up with one hand and dial 911 with the other. Words he was trying to say were not words, and words turned to letters, not in any order. His famous Texas drawl was no more.

When I was first allowed to see him in the ICU, his eyes remained big and piercingly blue. A tear fell from his left eye and rolled off his jaw. “My dearest, my darling, I’m here,” I told him. “And you’re here. Now we’re going to get you out of here.” I stayed on this theme, repeating it like a mantra. Don was tethered to tubes and wires and to those machines that played tunes of protection—and of death. I knelt. I prayed.

“Was it a massive stroke?” I managed to ask the several doctors. “It was a big one,” they said. A Big One. The left side of his lips drooped. The doctors asked him simple yes-or-no questions. If he understood them, he was to indicate by raising the toes on his right foot. Now and then they would move. Question after question from the doctors, and I had hundreds of my own.

“Do you know that I’m here?” I blurted out. His toes lifted slightly. “Do you know how much I love you?” A slight movement.

For the last 25 years Don had fought a blood cancer, CLL (Chronic Lymphatic Leukemia). But he was felled by something else, some other terror streaking through him on what was to be just another day together. We were both just 10 days away from starting our summer classes at UT. We would each teach a class at the same time, and we loved going to work as a team. Don was to teach his signature course on the JFK assassination (spoiler: Oswald acted alone). I can’t remember what I was to teach, though I did in fact teach. I do remember with certainty that the 30-some students I taught in that class were among the kindest souls I have had the privilege to be with. The best professor always learns from their students.

In my first class two weeks after Don died, I couldn’t have hoped for a better and more understanding group. It was the campuswide required class, English 316, a survey of American literature. If your professor tearing up was something you’d rather not have included on the syllabus, this class was not for you. But they were spectacular. One student hobbled in on crutches one day; she had broken three of her toes. After class, I sobbed in her arms. I would have been lost that summer without those caring students alongside me.

The neurosurgeon at St. David’s had attempted a lifesaving procedure on Don that amounted to going through the groin and up to the brain, where the blood clot was determined to be lodged. As the doctor explained to me in layman’s terms, it was like “scooping out a fish in a ladle.” He was resolute when he visited with me afterward. Usually, he said, this works on the initial attempt. He had tried six times, and there could be no more. The bill I received for the surgery was more than $55,000, but when his office got word that insurance would not cover it—our insurance called it, inexplicably, “an experimental procedure”—I never got another bill. I had told the doctor that day that Don was “well-known,” as if that fact just might save him. “Oh, I’m three chapters into Giant,” he told me, referring to Don’s final book, Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film.

Pretty soon in these cases, and generally, I imagine, the survivor envisions the victim walking through the front door once more. He’ll say, “Boy, have I got a story for you!” And when he doesn’t, you remember that he was sick, and he was so tired. But I’d thought Don was pretty invulnerable.

—

Don would have turned 80 on January 30, 2020. We would have marked that as we did most occasions, just us together, with our two beloved cats, Tommy and Viv. We lived in a cozy little two-bedroom, where I still live, a “garden home” they call it, on a bluff that rises above the Capitol of Texas Highway and backs up to an overgrown greenbelt with all sorts of vegetation and insects and animals. (Unfortunately for me, snakes like the rocks up here, too.) We might have watched a film, one we could both agree on, which could be a feat. I loved rewatching ones we’d both liked, because I already knew they’d be good, but Don always wanted to take a chance on the unseen. “If I’m teaching a movie, I see it plenty of times,” he’d tell me. “But think about all that’s out there. Time’s short.”

Perhaps we would have eaten out, always a challenge with Don, who was a rabid food critic. He was fiercely loyal to all most important to him: first and foremost, rural with a capital “R.” During his childhood, Big D seemed about as far away as Los Angeles. His mother, Myrtle “Joyce” Graham, was described by Don as a “frontier protestant,” and like her mother before her, Joyce was a dedicated cook of the kind Don admired most: country cooking, comfort eating. Vegetables were boiled with salt and a pinch of sugar to a soft consistency, and fish and meat were fried to a crisp. Biscuits were homemade and drenched with butter. The rules of Collin County cooking had come from generations of time-tested kitchens, and for Don, no Le Cordon Bleu chef could come close. Catfish must be fried whole and only in cornmeal. Chickens must be on the small side, not the bulbous ones Don would complain about at the supermarket, and be cut up by hand, like his mother did. I learned quickly such things about Don, because food to him was sacrosanct. Pretty soon after we started going steady, I confessed that I was the young woman tossing a salad in a New Yorker cartoon who declared: “I don’t cook, I don’t bake, but I make a kick-ass vinaigrette.”

It’s no surprise, then, that frequently during our marriage Don would prepare his favorite meal: pinto beans with ham hocks; turnip greens or spinach, or some attempt at greenery; and cornbread from a mix, with a stick of butter for each cast-iron pan he baked. The next day he’d eat the beans cold with a dollop of mayonnaise and cracked pepper on top. He had the timing down to the second for the perfect lobster boil, and we tried to take advantage of H-E-B’s frequent discounts on lobster tails. As he got older, he preferred vegetables over meat, though protein would have to be thrown in there somewhere and he would opine grandly about how nobody outside Collin County knew what in the hell to do with green beans. At family gatherings the women would serve the meal to the men at the table and stay on their feet in the kitchen while they ate so they could be ready to refill a man’s iced tea glass before it was halfway down. Don was plain old-fashioned about this country practice and had great respect for the quick and delicious service to the hungry men by good and patient female cooks, proclaiming it “a good system.” He could never lie about food. Imagine the guilt I feel about not being much of a cook, especially in my early years with Don. Yes, I was working on an academic career, but Collin County women could have done it all.

In 1958, Don entered TCU as a freshman. Though he liked the school, it proved too expensive, and he wanted to be able to concentrate on learning about literature without having to juggle a series of odd jobs. Transferring to the University of North Texas, Don began to find his literary critical voice. One of his mentors was the late, great English professor Martin Shockley, who was old-school all the way. When Shockley entered the classroom, he’d fling open all the windows because he didn’t like “sharing the fetid air with 25 undergrads.” He was a warhorse in his profession and recognized Don’s potential as a writer, but also called him out in class to rattle him. “Where sits Mr. Graham?” he once asked imperiously, glancing around the room. “Because in the essay I hold before you Mr. Graham would have you believe that the text we are reading actually speaks to … ” In his own teaching, Don took his own lead, and was much more casual.

Don was as shy as he was studious and confessed to not having a lick of sense about how to deal with the opposite sex. He was never a partier. From his parents he had inherited a solid Puritan work ethic that would stay with him for life. Holidays, to Don, could be interruptions—for his writing, and for getting mail. He always enjoyed opening the mailbox and seeing what was there, excepting bills. He held an almost fawning respect for the U.S. postal system and the exchange of letters. Computer technology positively confounded him. For Don, there was no amount of curse words that could adequately address the situation. When he hit a wrong key and paragraph marks would appear throughout his document, I’d be summoned for aid. All I’d do was push another button, but he’d react as if I’d swum the English Channel. “Goddamit B, get in here!” turned in a minute to “B, you’re amazing.” Often I’ve thought of the trouble he would have had teaching by Zoom, where I would have had to schedule my own classes at different times than his and, during his, sit beside him as a makeshift producer.

Don applied to graduate school at The University of Texas at Austin. While he was working on his master’s he commuted to San Marcos to teach freshman English classes at what was then called Southwest Texas State. After he completed his PhD, he headed to the University of Maryland for a post-doc stint, and after that, was hired as an assistant professor, tenure-track job within the vaunted, ivied walls of the University of Pennsylvania. At a U-Haul truck rental in San Marcos on his way out of town, he couldn’t figure out what was taking the employee so long to document his destination. Turned out the guy had been looking for Philadelphia under F.

At Penn, a colleague would wait until Don turned a hallway corner in their English department building, slap his right shank, and lift an imaginary pistol at Don, saying: “Stick ’em up, cowboy!” Though Don was hardly a cowboy, he found the cultural appropriation amusing and, later, his ticket to ride. Though he traveled across the continental U.S. and to Europe and Australia, he never stopped even attempting to shake his deeply ingrained Texanness. All he had to do was open his mouth and say … well, just about anything, and then that was thaaat. He finally bought a pair of cowboy boots at my insistence. Well, he flat looked like a Texan, and his lanky appearance and lopey walk alone led him into more than few misconceptions from others. In fact, he was as interested in modern Texas as he was in the state’s history, in its achievements and its failures—and he was equally knowledgeable about both. He was infinitely proud of the myriad of races and national identities that defined not only a modern, urban Texas, but had been such a key component of Texas history all along.

Penn launched Don’s Texas-themed academic career, where he was assigned courses on Western films. But only two of the five assistant profs hired with Don got tenure, and he was one of the other three. Fortunately for him—and would turn out lucky for me as well—he was hired in 1975 by the English department at UT Austin, where he quickly turned his dissertation on Frank Norris and naturalism into a book, and finally found a permanent home at the university that would become his professional home for the rest of his career.

It was here, 10 years after, in 1985, that I found myself like Don before me, attending graduate school in English at UT Austin. Suddenly we were within 40 acres of each other, and closer to what some of our students began to call the “Don and Betsy Show.” It had a wondrous 30-year run time.

—

I met Don in the spring of 1986. I had gotten my master’s in creative writing and a doctorate in British modernist fiction. Loving my newfound freedom on UT’s beautiful, hot-as-hell campus, a friend and I signed up for Don’s famous course, first created by J. Frank Dobie: “Life and Literature of the Southwest.” Literary and historical offerings concerning Texas were for me almost wholly unexplored, a gap in my learning that would dismay Don frequently throughout our relationship. That I couldn’t name at least three cogent facts about, say, Davey Crockett, was never less than appalling to him.

But Don’s class was full. “We’ll do something else,” I told my friend. “But Graham’s good,” she said. “At what?” I asked. “I can’t say for sure,” she told me, “But he’s got a rep.” So, we marched from the student union to the only place that could help: the UT Tower. “The Tower” became Don’s and my shorthand for UT administration and staff.

In the 1980s, the Tower housed a notorious woman who among other things measured the margins of PhD candidates’ dissertations. They would always be found wanting. She wore a ruler in her belt like a gunslinger. And it was this very woman who greeted us behind the front desk on the 11th floor. We were told Don’s class was closed. My friend asked to see her graduate dossier, and when the margin-measurer left to fetch it, my friend jumped over the desk and registered our UT EIDs in Don’s roster before she got back. Humming the Mission Impossible theme, we walked to Don’s first-floor Parlin office and knocked jauntily. “The class is closed,” he confirmed to us. “When’s the last time you checked your roster?” my friend asked, and I: “Is there a syllabus?” The class was packed, especially for a grad offering, and Don seemed unable to remember my name. One day he sauntered in, “make my day” Clint Eastwood style, and announced that he would no longer put up with our “undergraduate” noise, note-passing, and such other behavior. We’d just been a bit overly enthusiastic to be in his class, and I vowed never to forgive him for the rant.

We didn’t start off smoothly—he’d also interrupted my oral presentation to let another student who had a doctor’s appointment go. But something promising was already in progress. We didn’t start dating until after I had turned in my final paper, and I would be remiss not to point out that at present, UT faculty, staff, and students are not even allowed consensual fraternization. But Don and I met in the Bronze Age, and ours would become a true love story.

We spent five years developing our relationship. I could tell he didn’t know how to dress and set about attending to that. All our times together were enjoyable, even me sitting outside a men’s dressing room and Don coming out to model. As for his refashioning of me, his professional instincts started in early, educating me about his favorite state. (I was born in Puerto Rico and had come to Texas for my first year of high school.) I had plenty to learn and the best teacher. Our dates were to restaurants where Don would complain about the food, and just sitting next to him I found little to complain about at all. We rarely disagreed. Having both been married before, we weren’t gun-shy, but we tried to be careful and mature, letting time run its course. We spent all our spare time together, and when either of us traveled alone, we’d pine for each other the whole time. From the very beginning we had both realized the essence of what we thought it meant to be true soulmates.

We made it official, marrying on June 14, 1991, at Austin’s Four Seasons Hotel. Our honeymoon was in the French Quarter of New Orleans, the city of my father’s birth and one of our favorite places. Though we hadn’t known, there was a Formula One race taking place, believe it or not, in the Quarter. Streets were closed off, even to foot traffic, and revs from the engines were ear-splitting, rattling through the windows and walls. We stayed in our elegant hotel room, ordered room service, and hardly noticed the chaos outside. This established a hunkering-together process we’d already developed and that would continue for us until the end.

We were both very big on humor—laughing about things that can’t be changed seemed better than gnashing our teeth—and we implemented that humor purposefully. Donaldo’s humor was one of his calling cards, especially in writing, although as a well-known critic, he had his detractors. He liked to educate and entertain his readers. He knew he couldn’t please everybody, and he tried to be honest and ethical in his assessments. He was the stone-cold opposite of a literary snob, and his students recognized this in him immediately, flocking to his classes—like my friend and I once had—in droves.

At the end of the first day of a new semester, we’d ask each other how it went. I can’t remember a single time when Don didn’t report, “I already see potential. I think they just may be a great group!” If they weren’t a great group, they often became so after a few months under Don’s tutelage. I recall one of his students stopping me in the hallway, gushing, “Dr. Berry, would it be okay to say how lucky I think you are to be married to Dr. Graham?” I always agreed. I taught a course on Australian literature and film and appropriated a favorite Aussie expression: “Too right!” The Don and Betsy Show was almost too right: going to and from work together, hearing his students’ laughter coming through the walls of his classroom, lunches we shared, a sunset and night stretching before us. The real magic of love stories would be if they didn’t have to end. But part of the nights included prep for our next day’s teaching, and we were as committed to our work as to each other.

We both knew that teaching humanities was a game of diminishing returns. But to have a job you love must be among life’s great fortunes: to be with students, young people who actually wanted to talk, to exchange ideas with us. When he was in his 70s, I talked with him several times about the idea of retirement, something plenty of workers take as a given, but to which Don hadn’t given serious thought. Not that we had money saved to even think about it, but I was still surprised by Don’s ambivalence. “I … don’t know,” he’d say. “And just … do what?” Though salary concerns, and we had them, weren’t at the heart of it. Don plain liked going to campus, felt at home in the classroom, and enjoyed students and colleagues and intellectual discussions of every kind. Don was a living embodiment of Emerson’s cherished “observant life.” He would joke about eventually being wheeled into the classroom on a gurney, an IV in his arm, and announcing, “So today, y’all, we’ll be talking about the poet Siegfried Sassoon and World War I.”

On weekends we would take drives just to look around at our little world, listening to music I had put on for the road. Don’s favorite song was the Buck Owens and Dwight Yoakam duet, “Streets of Bakersfield.” A song I’d introduced to him was Robert Palmer’s “Simply Irresistible,” and he dedicated these lines from it to me: “She’s so fine, there’s no tellin’ where the money went.” (He thought this was funny, and true enough besides.) During one of these drives in what would turn out to be my last year with Don, he suddenly reached over and clasped my hand. “You are such fun to be around, B,” he said. “I don’t know if I’d told you that for a while.” It had been a while, but I had heard this loveliest of compliments from him so many times before. What did he know then? I would wonder later. What was he thinking then?

—

The first time I had my taxes done after his death, my CPA found a handwritten note from Don on the back of a document he had typed out listing work-related purchases. Don’s recognizable, scrabbly handwriting read: “All writing I have produced, including all unpublished materials, I leave to my wife, Betsy Berry.” It was dated three months before his fatal stroke. Don never complained about his health, which had been deteriorating for years before the end; he was simply the bravest man I will ever have the privilege of knowing. For my part, I stayed in complete denial, assuring him in my mind, if not to his face, that I wouldn’t ever let him go. That I alone could save him, and what’s more, I would. It was not only preposterous but the single most selfish thought I have ever had, may God forgive me.

Oh, we had the liveliest and luckiest of lives. At the end I wondered if perhaps this was a back payment of some kind, that perhaps for years now we had been in arrears for what we owed the universe for such supreme contentment, for sharing the kind of love some people never find. And now, as painful as it is to be without him, I am grateful for every second that ticked off the clock, for every entry in the long ledger that recorded our lives, our laughter, our love. I lost not just a husband. I lost Don Graham.

How often I revisit that last day before his life ended. I see him helpless on his death bed, his long feet protruding from the sheet, his face only an echo of the one I had so often held in my loving gaze.

“Can you tell me just once more that you loved me?” I ask him. “So many times, you’ve said it, now just this once more. That you loved me. That in your life, you so loved me. If so, lift your toes.”

There is no movement. The machines that hiss and spin and sing stop their movements, soon to be rolled away from one of the most vital men I have ever known. I recall feeling as if I am the only person in the room, in the world. I can hear nothing, not the dying machines, not the scurrying footsteps around me of doctors and nurses more familiar than I with toes that will soon be forever at rest.

I take off a sandal and lift my leg onto his bed, resting it beside his lovely left hand with its golden band. I ask the question a final time.

And I raise my toes.

Hours later, as dawn breaks on a June Saturday, Don Graham ceases to be, sun shafts shining on his face through the window of his room. At that moment, even the big and bold Texas sun seems merely to be going through the motions. And I tenderly kiss him goodbye. And I walk out of the hospital and into that sunlight. And it will be a long time before I will again find it cheerful or bright.

That long time continues. But Don lived a prolific and happy life, and I thank the stars daily for sharing one of their own, so intimately, with me. For comfort, I have the most exquisite memories to warm me through the coldest and darkest of nights. You are forever with me, my dearest. My darling Don.

Credit: Matt Wright-Steel, Courtesy of Betsy Berry (4), Bridgett Woody Scott