How Did DNA Kits Become so Popular—and What’s Next?

When I first think about signing up for 23andMe in early 2018, the direct-to-consumer genetics testing company is running a campaign called “DNA of a Champion,” and faces of former and current U.S. Winter Olympians are plastered all over the company’s homepage.

“Information is certainly one of the most critical pieces to anything,” alpine skiing champion Bode Miller says in a video. “But certainly in ski racing you need to know where your strengths are.” As a non-Olympic ski racer, I do not find this campaign particularly effective, but I put in my order anyway. To be curious about where we come from is a common human instinct. It may even be particularly American, since almost all of us who were born here know that our people began somewhere else in the world.

According to 23andMe, there are “two easy ways to discover you” (Ancestry or Health + Ancestry) and it’s a very simple three-step process: “Order. Spit. Discover.” I decide to splurge on self-discovery and go with the more expensive option. A few clicks (and $199) later and I have purchased their Health + Ancestry Service, which promises me over 75 online reports on my ancestry, traits, health, and more. Then I click off of former gold medal skier Julia Mancuso’s face and back to my inbox.

***

It didn’t used to be nearly this easy—or affordable—to gain access to your own DNA sequence. “The industry really kicked off in the most cottage-y way possible,” says geneticist and UT adjunct professor Spencer Wells, BS ’88, Life Member. We’re in his corner office in Patterson on the Forty Acres, where an acoustic guitar leans against the wall near his sleek white desk. Besides also being an anthropologist and author—with a PhD in biology from Harvard—Wells is an owner of the iconic Austin music venue Antone’s.

In 1997, Michael Hammer, a geneticist at the University of Arizona, published a paper in Nature that found a specific group of Jewish men—Cohanim—shared distinctive genetic traits. The research was biological evidence for an ancient belief: that Cohanim, or Jewish priests, are all descendants of the first high priest Aaron, the older brother of Moses. After the paper was published, Wells explains, Hammer found himself with a lot of men named Cohen calling him, wanting to know if they were Cohanim, genetically speaking.

“He’s like, ‘I’m an academic. I don’t do that,’” Wells says, but eventually the volume of requests convinced him, and he started analyzing their DNA through cheek swabs, charging money to defray the cost. A similar thing happened to Bryan Sykes, a genetics professor at Oxford University, who in 2001 authored The Seven Daughters of Eve, an internationally bestselling book about the origins of modern European women.

But that was pretty much it. “There was no real industry to speak of,” Wells says. And he would know. Wells launched the direct-to-consumer genetics industry.

[caption id="attachment_66181" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Wells in 2006 on an expedition to the Tibetsi Mountains for the Genographic Project.[/caption]

In 2003, Wells, along with the National Geographic channel and PBS, premiered a documentary, Journey of Man, featuring his research using the Y chromosome to study human migration patterns. To promote the film, National Geographic tested celebrities in big markets all over the world, like Jackie Chan in Hong Kong, and told them where they fell in the Y chromosome tree. People were fascinated, Wells remembers. Even though the science was very basic, the idea that you could learn things from your DNA seemed to captivate people. “That was when I first had an inkling that there’s probably a market there for this,” he says. “If you do it right.”

After Journey of Man, in 2005, National Geographic and Wells launched The Genographic Project, and with it what would become, unintentionally, the first major direct-to-consumer genetic testing kit. The mission of The Genographic Project, which Wells led until 2015—is research, and specifically the work of analyzing historical patterns in DNA to understand migration and shared genetic roots. It focuses on far-flung populations from field researchers stationed at 11 regional centers around the world. From the beginning, Wells felt strongly that there should be a public participation component, too.

“It wasn’t just an academic exercise,” he explains. “It’s the story of all of us.” Plus, by offering “citizen scientists”—a term Wells says he and his team coined—the opportunity to get involved, people could choose to donate their data, and, through the Legacy Fund, they could help give something tangible back to indigenous populations in the form of cultural preservation grants. (Wells says they gave away $2.5 million in 95 grants between 2005 and 2015.)

When Wells floated the public participation idea with John Fahey though, he remembers the then-CEO of National Geographic told him, “Let’s calm down with this whole public participation thing.” Fahey thought they might sell 1,000 kits over a few years. Instead, Wells says, they sold 10,000 on the first day.

Entrepreneurs, scientists, and the health care community took note. In 2007, Wells says he got a call from Anne Wojcicki and Joanna Mountain: they were getting ready to launch, and they wanted to give him a heads up. “The success of Genographic has shown us there’s a market for consumer genetic testing,” Wells says they told him. “You guys are doing ancestry. Our focus is going to be on the medical side.”

Originally priced at $1,000, 23andMe didn’t immediately bring a surge to the market. Neither did Navigenics, a rival company that originally priced its kits at $2,500. But in 2009, 23andMe lowered prices, and its customer base began to grow. Around 2012, Ancestry got in the game with AncestryDNA, and by 2015, over one million people had been tested through the major companies. Within a year, that number had nearly doubled.

According to an estimate by Illumina, the company that makes the technology that all major direct-to-consumer genetics companies depend on, 7 million people tested their DNA in 2017 alone. This past holiday season, between Black Friday and Cyber Monday, AncestryDNA sold around 1.5 million testing kits. There’s a company called Vinome that will analyze your DNA and taste preferences and suggest wines “perfectly paired to you.” Vitagene offers “supplement plans tailored to your genetics.” And Wisdom will give you “a detailed family tree going back three generations”—for your dog.

It’s not necessarily surprising that the industry has taken off in the way it has. Stories and science have been intrinsically important to humans for a long time. And direct-to-consumer genetics is—or at the very least, is marketed to be—a near-perfect pairing of those two pillars that societies so often use to tell both collective and individual narratives. As AncestryDNA suggests in its recent commercial, “Kyle,” which features a man who grew up thinking he was German, but swaps his lederhosen for a kilt when he discovers he’s actually mostly Scottish and Irish, our DNA is a way to help us paint a story of who we are, understand what that means about our identity, and even dictate how we should move through the world.

In the United States, understanding where we come from carries even more weight, Wells says. “We’re a nation of mutts. We’re all hyphenated Americans. And nobody knows anything about what comes before the hyphens, so they want some sort of connection back to that. So it’s like, ‘I’m Irish-American. But what does that mean?’’’

Deborah Bolnick, an associate professor of anthropology at UT and a faculty research associate at the Population Research Center, explains the popularity in direct-to-consumer testing this way: “Science and in particular genetics hold a kind of cultural authority in our society. We see science in this country as, in many cases, a core way of understanding and knowing what’s true about the world. We have real tendencies toward a kind of genetic determinism, seeing lots of important things about us as being rooted in our DNA, in our genetic makeup, and these tests very much fit within those perspectives.”

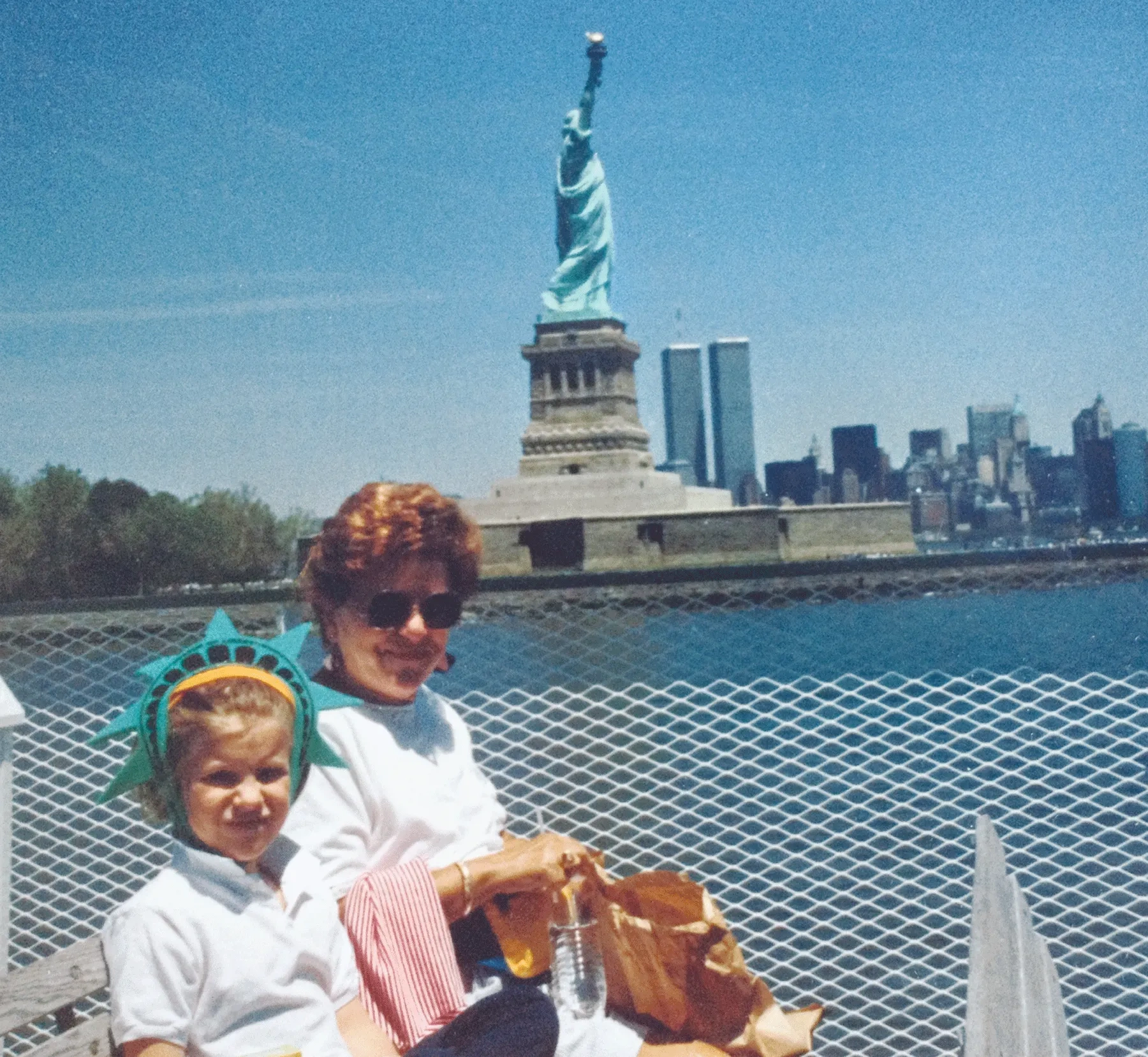

[caption id="attachment_66175" align="alignright" width="300"]

The author and her grandmother, Dot Sokolove, circa 1994.[/caption]

Of course, the massive growth of direct-to-consumer genetics has created not just a thriving industry, but a host of controversies and questions, many of which tie directly back to that very idea of cultural authority Bolnick raises. Just how much weight should we give the results of these tests? What are we really learning about ourselves, and what are the implications of turning over the keys to our DNA data?

***

Three days after I place my order with 23andMe, it arrives at my door in cuter packaging than you might expect for something called a “home-based saliva collection kit.” Following instructions, I spit into the collection tube, slip my sealed spit into the provided plastic specimen bag, and package it in the pre-addressed box. The next day on my way into work, I drop my DNA into a mailbox like I would an online return.

All humans have about 99.5 percent identical DNA. The small differences, called variants, are what make us unique, and can sometimes be linked to certain health traits. According to the popular YouTube channel “Smarter Every Day,” which got a behind-the-scenes tour of LabCorp (the company that provides genotyping services for 23andMe), once my spit arrives it likely heads onto a conveyor belt to be opened before a technician extracts DNA from cells in my saliva. Then my DNA is processed on something called a genotyping chip—specifically, a custom Illumina HumanOmniExpress-24 format chip—that reads hundreds of thousands of variants in my genome.

Using automated gadgets, tiny syringes, and microscopes that look like much more serious and snazzier versions of what was in my high school biology classroom, 23andMe unzips the double helix of my DNA, and a machine places one side of it into the genotyping chip. The chip, which looks like a cross between a floppy disk and negatives from a film strip, has thousands of probes on it that are known to match the human genome, and once my unzipped double helix is placed alongside those probes, the two bind together. From there, 23andMe is able to look at specific locations for variants in my DNA, and create my report based on what they find.

About six weeks after I first send my spit off, a festive-looking email arrives in my inbox. “Sofia, welcome to you!” reads a card popping out of an envelope surrounded by colorful doodles. A big blue button underneath reads: “View your reports!” I immediately close the email. The idea that I might uncover a family secret or learn that I am predisposed to a serious disease through something that looks like an Evite to my nephew’s fifth birthday party feels very strange.

Until this moment, I have not given much thought to what I could discover through genetic testing, which I recognize as a sort of privileged ignorance. For many, genetic testing is a way of answering questions they have had all their lives: Who was my biological father? Do I have any siblings? As a descendant of slaves, what part of Africa is my family from? For others, like my friend who discovered a half brother he did not know he had through 23andMe, genetic testing answers questions people didn’t even know to ask.

For me, it is neither. Before I open my ancestry results, I travel home to Bethesda, Maryland, and ask my parents over dinner to refresh my memory about my family history before the big reveal. Once they confirm that I’m some combination of German and Eastern European Jew, I open up 23andMe to drumroll noises from both of my parents—we are a few cocktails in. The results are exactly as expected. A pie chart tells me that my “ancestry composition” is 100 percent European. Or, more specifically, 48.2 percent Ashkenazi Jewish, 14.6 percent British, 14.6 percent German, 18.1 percent Northwestern European … plus a host of other small percentages from across Europe.

But—and this is where it can get confusing—what 23andMe is telling me isn’t quite that my relatives were 100 percent European, or even that I am. Genetic testing is about comparison. All direct-to-consumer genetic companies are determining information about your DNA by comparing it to others. When 23andMe matched up my unzipped helix on their genotyping chip, the data they compared it to most likely came from the database of consumers (nearly 4,000,000 and counting) who have already sent their spit off to them.

They aren’t finding matches between my DNA and my actual ancestors, because they don’t have my ancestors’ DNA. “Companies are marketing these tests as telling you something about where your ancestors lived or what communities they belonged to,” Bolnick says, but “in reality what they are usually doing is telling you where you have relatives who are alive today.” It’s a small but significant distinction that isn’t always clear to the average consumer.

In early May, I start to get sponsored Instagram ads from 23andMe, suggesting I choose a World Cup team to cheer for this summer based on my ancestry. I have always known that the town my great-grandmother was from isn’t considered Poland these days—it’s actually modern day Belarus. This checks out with 23andMe, which tells me my ancestry composition is 1.7 percent Belarusian.

So does “Rooting for my Roots,” as the campaign is called, mean feeling bummed Belarus isn’t in the World Cup this summer, or cheering for Poland? And if I didn’t already have this knowledge of my family history, isn’t it possible I could, based on my 23andMe reports, feel disappointed in a soccer team from a place my great-grandmother had never even heard of?

The whole premise (particularly the idea of an Eastern European soccer team winning the World Cup) is, of course, silly, but it’s also illustrative of a larger point that Bolnick likes to make. For the past decade, Bolnick has been, in her words, “part of a set of scholars who have been trying to provide some cautionary notes to the public conversations about these tests.”

Bolnick, whose research uses DNA from ancient and contemporary peoples to help reconstruct population histories in the Americas, explains that the tools used in direct-to-consumer genetics are in many ways a direct outgrowth of methods that have been developed in anthropological and human populations genetics. But when you shift from talking about groups of people to individuals, it becomes trickier to interpret the results says Bolnick. “Sometimes the answers that they provide aren’t as clear-cut as test-takers might want.”

That is especially true if the consumer isn’t of European descent, because a majority of the direct-to-consumer genetic testing that has been done so far comes from people who are of European descent, and the data sets that most companies are using are likely primarily made up of paying customers. If your ancestry does not closely match the DNA of those already in the data set, your results are likely to be less accurate. “Different companies have different reference data sets and different algorithms, hence the variance in results,” a spokesman from 23andMe told Gizmodo back in January, when one of their writers, Kristen V. Brown, was reporting on how she sent her DNA off to three different companies and got three entirely different ancestry results.

Ancestry percentage tests are inferring ancestry, but in a roundabout way, explains Wells. “What you’re actually inferring is your affinity for present day populations that shared something in common in the past. And so the choice of present day populations will guide whatever results you’re going to get.” To help correct for the bias being built into analysis, 23andMe can actively go after more diverse data.

A new initiative, launched this spring, is an attempt to do just that. 23andMe’s Populations Collaboration program, is, in the company’s words, meant “to expand and improve our Reference Data Panel through capturing the genetic diversity of populations around the world who are underrepresented in our database and in genetics research globally.”

The idea is that 23andMe will offer funding and support to scientists working with populations underrepresented in genetic researching, and in turn, have access to that data to diversify their DNA database and improve the accuracy of their ancestry reports.

Senior Director of Research Joanna Mountain called the initiative a win-win in an interview with Gizmodo. “We get access to the genetic data and so do the researchers,” she said. But what does 23andMe having my—or anyone else’s—genetic data mean for information security?

***

When the Genographic Project initially launched, its at-home test kits were anonymous, Wells says. There was no way to connect people to their genetic results, partly because Wells and his team were worried about having to break trust or privacy bonds if, say, the FBI came to them with a warrant. “We didn’t want to deal with that,” he says. “There was a random code that went into every kit, and that was the only way you could log in to access your results.”

But people started losing their boxes, and they complained about it. “They were like, ‘Can’t we just set up an account, linked to our email address?’” Wells remembers. “And we were like, ‘That’s precisely what we didn’t want to do.’ And they said, ‘We don’t care. We’re willing to give up that privacy.’ So now it’s the standard.”

Not everyone, though, feels so indifferent about giving up their privacy—in fact, that’s exactly why Bolnick tells me she would never send her DNA off to any company (although she has, of course, analyzed her own DNA). “I’m not comfortable,” she says, “not knowing exactly what will happen to my sample if it is in somebody else’s database.” And it’s true: I consider myself a careful reader, but despite the pages of consent forms I clicked through when registering my saliva sample, I realize I’m not exactly sure what all I agreed to.

And my results are the least of what companies like 23andMe are interested in, Bolnick says. “They want access to samples that they can use for other research purposes to try to identify genetic factors that play a role in disease or health or reactions to pharmaceuticals so that they can partner with other companies to make money from that. When you submit your sample to 23andMe, you are consenting for them to do other things with your DNA unless you explicitly opt out.”

Bolnick makes another point about privacy with me I hadn’t considered. “This is not something most of us ever think we’re going to worry about,” she says, “but there’s at least one case of police subpoenaing to access genetic information from a company’s database in the context of criminal investigations.” She’s eerily on point. Less than two weeks later, news breaks that detectives used a public genealogy database to identify and ultimately track down the Golden State Killer, who had been on the loose for more than 30 years.

***

I don’t immediately open my health results at the dinner table with my parents—I’m worried it might dampen the mood. In early March, while waiting for my results, the FDA cleared 23andMe to report on three specific BRCA1/BCRA2 breast cancer gene mutations, a move that Donald St. Pierre, acting director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, called a “step forward in the availability of DTC genetic tests.” Back in 2010, 23andMe was reporting these mutations to customers without FDA approval, but stopped in 2013 after warnings from the agency, which announced that such results required regulatory approval, as they could be “inaccurate and risky” to customers. Just last spring, in a win for 23andMe, the FDA softened its policy, and now have expanded it to allow reports on the BCRA1/BCRA2 mutation.

In the world of predictive testing, the BCRA1/BCRA2 gene mutation can be particularly alarming because of how dramatically its mutations can increase cancer risk—women with certain variants can have a 45 percent change to 65 percent chance of developing breast cancer by age 70. It’s also a mutation that can inspire drastic action—it was after testing positive for BCRA1 that Angelina Jolie opted for a double mastectomy, documenting her decision in a New York Times piece. I could not tell you the name of a single other gene mutation, but because BCRA1/BCRA2 is significantly more prevalent in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (and because both of my grandmothers had breast cancer) I cannot remember a time when I have not known—and been terrified of—those four letters.

Thankfully, I don’t test positive for any of the three BCRA variants 23andMe tests for, although 23andMe is quick to point out that I’m not in the clear: “However, more than 1,000 variations in the BCRA1 and BCRA2 genes are known to increase cancer risk, so you could still have a variant not included in this test,” the report reads. The whole experience mirrors opening my ancestry reports. Ahead of time, I imagine I might discover something concrete, but as I delve into the results, I actually feel more confused.

Dr. Michael Pignone, the inaugural Chair of the Department of Internal Medicine and a Professor of Medicine at the Dell Medical School, says I’m probably not the only consumer feeling this way.

Pignone is in favor of technology, and really any tool, that will engage patients more in their health and health care. In fact, his research—which is focused on chronic disease screening, prevention and treatment and on improving medical decision making—is often centered around it.

“The patient in the end is the person who suffers the consequences of good or bad health decisions—you want them to be engaged as much as they want to be engaged,” he says. And so to Pignone, in theory, direct-to-consumer genetic testing has potentially real advantages—the results go directly to the person who stands to benefit from having better information.

But he’s worried that in this case, our technology may be getting ahead of us. “Genetic testing is full of uncertainties,” Pignone says, “and we don’t even understand all of the uncertainties we are bringing into a patient’s knowledge, especially as we begin to test for more and more.”

It used to be that genetic testing was done in a very controlled way: with a genetic counselor looking for one specific genetic mutation, for one specific set of diseases, and the results of that mutation. Now, Pignone explains, to be able to seek the whole genome on such a large scale is overwhelming. It will hold potentially good information, potentially harmful information, and plenty we don’t know. Plus, before it was direct-to-consumer, those being genetically tested were risk selected, and so the chance that information gleaned would be meaningful was greater. Now with the accessibility of direct-to-consumer genetics testing, low-risk populations are being tested much more frequently—but because the data we have about the significance of mutations was derived in a high-risk population, it can be hard to know how to interpret those results.

As Bolnick points out, 23andMe is in the business of gathering immense amounts of health data. But Pignone says it would be hard for them to use that toward understanding how to interpret mutation results for low risk populations because they are missing a key piece of the puzzle-outcome data. “So let’s just say now you have given your entity genetic information to 23andMe,” Pignone says “But what they don’t know is whether you are going to go on in five years and have a heart attack or develop breast cancer or die.Without the outcome data, it’s hard to match some of the genetic data to what actually happens.”

What concerns Pignone most, though, is what he sees as a lack of high-level support for how to use all of the genetic health information you receive from a direct-to-consumer kit like 23andMe. “And I wouldn’t give you the cop out answer of just talk to your doctor,” he says. “You walk in a doctor’s office and throw down a metaphorical 200 page document and say, ‘Here go through this for me.’ If we haven’t given them the tools to do that, I wouldn’t want to give your readers a false certainty that every doctor out there is ready to process all this information right now.”

***

After results are revealed, I head back to Austin and visit Wells again. I want to know what’s next. I’ve already given almost $200 (and my data) to 23andMe, but I’ve learned nothing that feels especially revelatory, and am simultaneously stuck with what feels like an overload of reports that are missing context. I’m not alone. “It’s a well-known issue within the consumer genomics industry,” Wells says. “Most people, like 90 percent of people, will check their results once and never again.”

Wells is hoping to change that with his new startup, Insitome. Founded in 2016, Insitome’s vision is to become the first genomic media company. “The OS for your genome,” Wells likes to call it. “This immersive experience that allows you to understand what your DNA means to you.”

On a literal level, what that means is building out apps and products for a company called Helix, which sequences your exome once (a process Wells explains provides 100 times more data than genotyping) and stores that data in the cloud. Consumers can then “unlock” their DNA through a marketplace of personalized products—like an App store for personal genomics. The apps Insitome is building for Helix are focused on ancestry, but go beyond percentages to get at how your ancestry can have an impact on the traits that you recognize in yourself—like lactose intolerance, or what traits you may have inherited from Neanderthals. There’s also a weekly podcast and blog posts with titles like “Lactase persistence: the Why and How.”

“We want you to be able to sit down on a Sunday afternoon,” Wells says, “and instead of binge-watching Netflix, you can binge watch your DNA.”

Learning through my 23andMe traits report that I have a high caffeine metabolism feels like a solid piece of information to wield over friends that judge me for a 5 p.m. coffee. And I brag to everyone who will listen about my muscle composition, which apparently is, ahem, “common in elite athletes.” The appeal of Insitome, to me, is the idea of delving into my genetic traits even more. There’s just something inherently compelling about learning why I am the way that I am.

“It’s our desire to understand ourselves,” Wells says. He likens it to carrying around an incredible, illuminated manuscript that you’re unable to read. “You know that it holds all of these secrets about who you are, where you came from, and where you might be going, but you can’t read it—we are helping you to read that, and to understand what it means.”

Looking to the future, Wells wants to perhaps expand into other product areas like a behavior app which, using genetic data and polygenic risk scores could help consumers understand where they fall on various spectrums. The idea, Wells says, is that learning about our own behavior could help us live our lives in ways “better tailored to [our] innate makeup.”

When I ask Wells about the potential risks of emphasizing our predetermined traits, he answers with confidence—and optimism. “No one is saying that on the basis of a genetic test that society should make decisions for you. What we’re saying is that individuals might be more empowered if they understood more about themselves genetically,” he says. “I think it’s a huge leap to go from that to imagining that we would create a Gattaca. I don’t think anyone really wants that.”

***

Bolnick often finds herself fielding questions about whether to take a direct-to-consumer DNA test. “I never feel like it’s my place to say, ‘You should take this or you should not,’” she says, “but rather to simply say, ‘Here’s what these tests can tell you. Here’s what they’re unlikely to tell you,’ so that each person can really come to their own decision.”

Weighing that balance is exactly what I find myself doing at the end of all this, nearly four months since I ordered, spit, and discovered. I’m concerned about privacy, and I feel a little indignant about the fact that in some lab somewhere my DNA is helping 23andMe profit. (Or at least, I think they are: I didn’t officially give 23andMe permission to “store” my DNA for research purposes but given everything I’ve read, it seems safe to say that I no longer fully own my own DNA.)

But, just like my DNA, my experience is unique. A friend of mine recently learned who her grandfather was through genetic testing. When I ask her mom—who at the age of 65 was finally able to answer the lifelong question of who her father was through 23andMe—whether she’s bothered by them owning her DNA data, she answers instantly: “Not at all!” For her, what she gained was so valuable, the tradeoff is entirely worth it.

“Your identity is self-determined and socially determined,” Bolnick says. “It’s who you are, it’s made up of ... in large part your experiences of the world; who you connect with, what groups of people, family or otherwise, that you feel you fit in with, and that’s something that’s really personal and socially situated in your life.” A DNA test can’t tell you that that’s wrong, argues Bolnick, because those experiences are the way you feel. That feels valid to me. But as the DTC testing industry continues to grow and expand, it also seems valid that the ways we engage with our DNA—by streaming our genome, as Wells would put it—will also become part of those experiences that help to determine identity. And to me, that seems OK.

Giving people the power to educate themselves about their DNA helps us to add scenes to our own personal movies, the ones we each star in inside our own heads. No one—not even our parents or partners—are going to be more interested in the narrative of our own lives than we are. And while what’s driving us may be narcissistic, seeking more information for our own stories is helping us to write our collective one, too.

In 2009, a woman wrote to Wells at the Genographic Project. “Love the project,” she told him, “but you told me I carry a Central Asian or Siberia mitochondrial DNA, and I know for a fact that my ancestors came from a little village just outside of Budapest, in Hungary. You must have gotten it wrong.”

Wells was excited when he saw this email, because the Hungarians are a linguistic outlier in Europe. He had his team pull data from over 2,300 people of Hungarian descent after she reached out, and saw the Asian lineages at a frequency of 2 to 3 percent, which, Wells explains, fits with the Hungarians’ linguistic connection to Asia but had not been seen before genetically with smaller sample sizes.

“The whole thing is not that large quantities of data allowed us to see that,” Wells says, still visibly excited after all these years. “The cool part is we wouldn’t have looked for it if that woman hadn’t asked about it. Empowering people to answer those questions themselves is really important.”

Illustration by Marcos Chin; Wells photograph by David Evans

An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of a company that curates DNA-based wine preferences. It is Vinome, not Vimone.