Changing the World, One Constitution at a Time

When America's Founding Fathers drafted the world's first constitution, they set a radical precedent. Since then, constitutions have been written, rewritten, and ratified the world over.

Now, with the help of Google, a UT professor is making the drafting process so much easier.

The Constitution of the United States is a unique piece of writing, and it was a revolutionary bit of law-making in the late 1700s. It's also the model for hundreds of national charters that came after it, nearly all of which borrowed its structure, style, or concepts. For more than 200 years, the document has remained roughly the same, save for a few amendments.

In a letter written to James Madison on Sep. 6, 1789, Thomas Jefferson expressed his thoughts on the foundational document written and debated just two years earlier. Despite Madison's status as the father of the Constitution, Jefferson was frank. "Every constitution ... naturally expires at the end of nineteen years," he wrote. "If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right." It's an opinion that may surprise some Americans used to the idea of the Constitution as the "law of the land," an idea reinforced in countless high schools and college lecture halls around the country.

So, why has that document—arguably the glue that holds American democracy together—lasted so long, when a great mind like Jefferson said it should be trashed?

"There's no reason to rewrite the Bible when you can just change doctrine," says UT professor Zach Elkins. Americans haven't made major changes to the Constitution, he says, because we can simply change our interpretation. That's the beauty of what he calls an abstract document. But the American document is an outlier. Most are both more expansive and more expensive.

No matter the length, constitutions are vital parts of every nation's character, whether they're short, broad documents or long, finite, legalistic tomes. They're the foundations—thick, thin, sturdy, or shaky—for nearly every nation on Earth for the last 226 years. And Elkins is an authority on the subject, traveling and consulting on new documents in addition to researching them.

That's why he is one of the leading minds behind a website called Constitute, a bold program to help the world write better constitutions. It's an outgrowth of the Comparative Constitutions Project, a years-long effort to read and catalogue every national governing document.

And there's a lot of them. Around 900, in fact. After beginning to collect data on constitutions, Elkins quickly realized it's a project that could prove useful to drafters. Before Constitute, constitution writers had an incredibly challenging job. "Imagine disappearing in the library with 3,000 books around you, trying to carve out excerpts on any given topic," Elkins says. "But to jump on a nice web application that's clean, crisp, beautiful and read some constitutions, that's a little more inviting."

Before joining forces with Google, Elkins and his team had already tried to drum up support with the usual suspects, like the National Science Foundation, but they didn't have the Glass-making, company-acquiring, Internet-defining folks from Mountain View in mind. At a conference, Elkins happened to bump into the Google Ideas team, a group he describes as wanting to help emerging democracies. The Googlers were impressed by the Comparative Constitutions Project and to Elkins' delight offered a grant to develop the site. Then they offered engineering support, and the site even got its own Google project manager.

Constitute is a more inviting space for policymakers around the world. Of course, you can just browse for fun, too. Thanks to the partnership with the web search giant's self-described "think/do tank," the look of the site is smooth and crisp. Its features are intuitive and, yes, even fun. That simple user interface might even help constitution writers, says Elkins, who could stumble upon topics they may not have considered.

The platform makes it easier to cross paths with previously unknown ideas. Search by year, region, country, or topic. It's all there in a glossy, easy-to-use package.

Elkins' baby is all grown up. Out in the world now, the project is ready to help legislators in Iceland, where the government crowd-sourced a new constitution, and Norway, home of the world's second-oldest document which celebrates its bicentennial next year.

[pullquote]"It's utterly eerie in so many ways," Elkins notes. "Incredibly strange, and I'm sure there's some conspiracy theorist out there or some astrological follower who thinks that this is the coolest thing in the world."[/pullquote]

How many people are writing constitutions? More than you'd think. Unlike the American version, most documents are longer and more specific. They barely make it past their teenage years, too. According to Elkins, the average lifespan is just 19. Exactly the amount of time Jefferson suggested in 1789.

"It's utterly eerie in so many ways," Elkins notes. "Incredibly strange, and I'm sure there's some conspiracy theorist out there or some astrological follower who thinks that this is the coolest thing in the world."

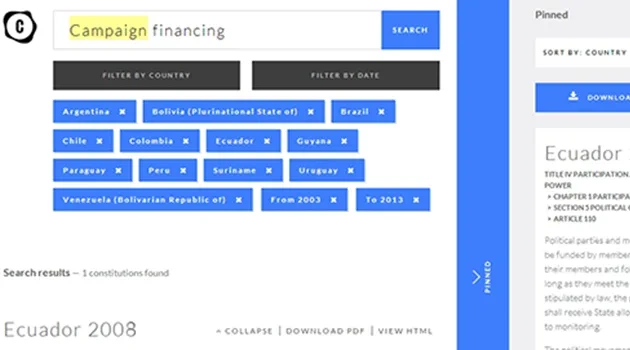

Below, the Constitute interface in action.

Though Illuminati-fearing theorists may like it, Elkins' research is best suited to people doing the real-life work of writing such documents. How does Constitute help modern-day founding fathers (and mothers)?

Let's say you're in the Brazilian parliament—just go with it—and you're on a legislative subcommittee for campaign finance laws. You want the best ideas for Brazil's new constitution, ensuring that your laws are based on tried and true policies, and that they reflect the culture of Brazil. Not a problem. Search for campaign financing in Constitute, and you'll have 36 results that you can pin, or save for later, quickly email to a colleague, or print out in a nifty automated PDF.

Need something more? You can distill those 36 down to four by selecting only South American countries. You can pare it down even further by only selecting documents written in the past 10 years. Only one is left, Ecuador.

The real beauty of it, however, is getting to sleep early, and with a head full of good ideas. "In the past, that would happen by combing through thousand of books, staying up all night," Elkins says.

Not anymore. Just search and click and, as Elkins says, "voila, you're done." No need to worry about forgetting all those good ideas while you doze either—they're safely pinned in Constitute. It's enough to make Thomas Jefferson jealous.

Photo courtesy Kate Ter Haar via Flickr Creative Commons.