Texas Loses a Trailblazer: John Chase Dies

John Chase's parents studied education in college. But when they applied to teaching jobs, they were always turned away because of their race. So Chase's father became a postal worker, and his mother worked as a maid.

"They are the reason I made it through college," Chase told The Alcalde in 1996. "Education had always been important in my family ... I figured the best place to get what I needed would be The University of Texas at Austin."

When Chase, MAr '52, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, died last Thursday, the University lost one of its most determined pioneers.

In 1950, Chase became the first African-American to enroll at UT, just as the landmark Sweatt v. Painter case was heading to the Supreme Court. Chase didn't know UT was segregated until the Dean of Architecture, Hugh McMath, asked him, "Are you familiar with the case that's in front of the Supreme Court right now?"

Chase was vaguely familiar with the case—and from his parents' experience, he was deeply familiar with how often African-Americans got the doors of the ivory tower slammed in their faces. But that didn't daunt him. With McMath's encouragement, he submitted his UT application.

Just two days after the Sweatt v. Painter ruling, Chase enrolled at UT. Reporters and cameramen chased him on campus; hateful letters poured in by the dozens.

"But for every negative thing that happened, I declare there was a positive," Chase told The Alcalde. "I had some great friends there, even during that time."

After earning his architecture degree, Chase applied to firms all over Texas. None would hire him, so he started his own firm—after selling his home to raise start-up funds. He became the first African-American licensed architect in Texas. For the next decade, he was the only one.

Chase helped design Houston's landmark George R. Brown Convention Center, among hundreds of other projects. He also had a passion for working on schools and universities, including buildings at Texas Southern University, Houston's Booker T. Washington High School, and UT, where he designed the Myers Track and Soccer Stadium and a $7 million West Campus parking facility. Chase even worked abroad, designing the U.S. Embassy in Tunisia.

He was also the first black member of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, a post President Jimmy Carter appointed him to in 1976. Among the projects he contributed to in Washington was the design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

In 1998 he was chosen as president of the Texas Exes, where he was a founding member of the Black Alumni Advisory Committee. And he passed his devotion for education on to his three children, who are all thriving attorneys.

In 1996, Chase told The Alcalde that he felt lucky to get paid for work that he loved. "The best part of the job," he said, "is to conceive of something, to watch it grow, and see people enjoying the building you've designed for them."

UT president Bill Powers calls Chase a "pivotal and inspirational figure" in the University's history. "As challenging as his time as a student was, he would return to become president of the alumni association, design a building for the campus, and remain involved in many important ways," Powers says. "His passing leaves a big hole in the UT family."

Current Texas Exes president Machree Gibson, BA '82, JD '91, Life Member, who as the Association's first female African-American president follows down a path Chase blazed, calls him "a very fine role model."

"I am so proud that it is his signature on my Texas Exes Life Membership certificate," Gibson says. "Hopefully, African Americans are proud now that it is my signature on their Life Membership certificates."

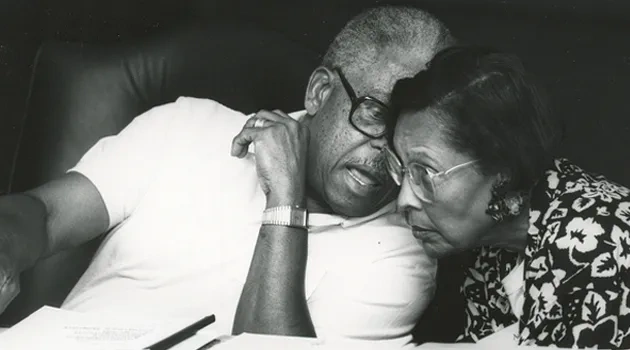

Top photo: Chase in 1996. At right: Chase working with Ada Anderson, MEd '65, Life Member, Distinguished Alumna, in 1993.