There’s a Magic to Music at the LBJ Library

When visitors first step into the “Music America” exhibit at the LBJ Presidential Library, they’ll hear the faint, soulful tones of a recording of the legendary Bessie Smith singing the “St. Louis Blues” a room over. While not technically the first sound cue of the space (a video of music experts framing the collection plays right by the entranceway), the blues is a fitting first soundtrack to an American music exhibit. Through music, the personal becomes universal.

Initially penned by W.C. Handy about a real-life moment where he overheard a St. Louis woman anguish about her husband’s cold-heartedness, the song well captures how an individual point of connection or difficulty can blossom into something bigger for a community and culture. “For us, music is an endlessly necessary nourishment,” an exhibit placard reads. “Great American songs define our spirit and our soul. They chronicle our history and shape it, too.”

The exhibit’s full name is “Music America: Iconic Objects from America’s Music History.” It comes about as a collaboration between the LBJ Presidential Library and The Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music, an organization that serves as the official repository for the musical legacy of Bruce Springsteen. The Center’s curation work brings together artifacts related to music icons including Dizzy Gillespie, Gloria Estefan, Taylor Swift, and more. Legendary instruments, garish performance outfits, handwritten letters, and lyric notes have all found a temporary home on The University of Texas campus. The exhibit runs until Aug. 11, 2024.

“By focusing on iconic objects from American music’s past and present, we get a sense of the magnitude and complexity of our music story and the importance of those artists and technological innovations that star in it,” a placard reads.

The dark blue walls of the exhibit contrast the otherwise white-walled first floor of the Presidential Library, encouraging visitors to attune their senses and focus their attention. The first few rooms cover the 1600s through the 1800s, notably drawing attention to and rejecting the colonial notion that the songs and chants of Indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans were “savage.”

Placards establish emerging Negro spirituals, a type of music consisting of transformed versions of Christian hymnals sung by enslaved folks, as the first “truly American music form,” as much of the music enjoyed by early colonists was still largely the stylings of European musicians. As it continues, the exhibit zooms in with greater detail on the individual decades of the 20th century. The ’60s gets a good deal of love, which speaks to the exhibit’s creation and why the LBJ Library made for a natural first host.

“Not only do we have a longstanding relationship with the Library, but so much of America’s greatest music history occurred in the 1960s when President Johnson was in the White House,” Springsteen Archives founding executive director Robert Santelli said in a press release.

In a thoughtful nod to the city, one of the contemporary artifacts is a poster for Antone’s, the beloved Austin music venue that has existed in some form or another since 1975 and continues to host music legends today. The poster highlights the renowned B.B. King and Bobby “Blue” Bland, both of which had a deep history with Austin playing in the Chitlin’ Circuit (a colloquial name for the performance venues that sustained Black entertainers, especially during segregation) in East Austin.

“It seemed only natural that this exhibition, which also celebrates America’s 250th birthday in 2026, begins in Austin, one of the country’s most important music centers, and will then travel to other presidential libraries and museums across the country,” Santelli said in a press release.

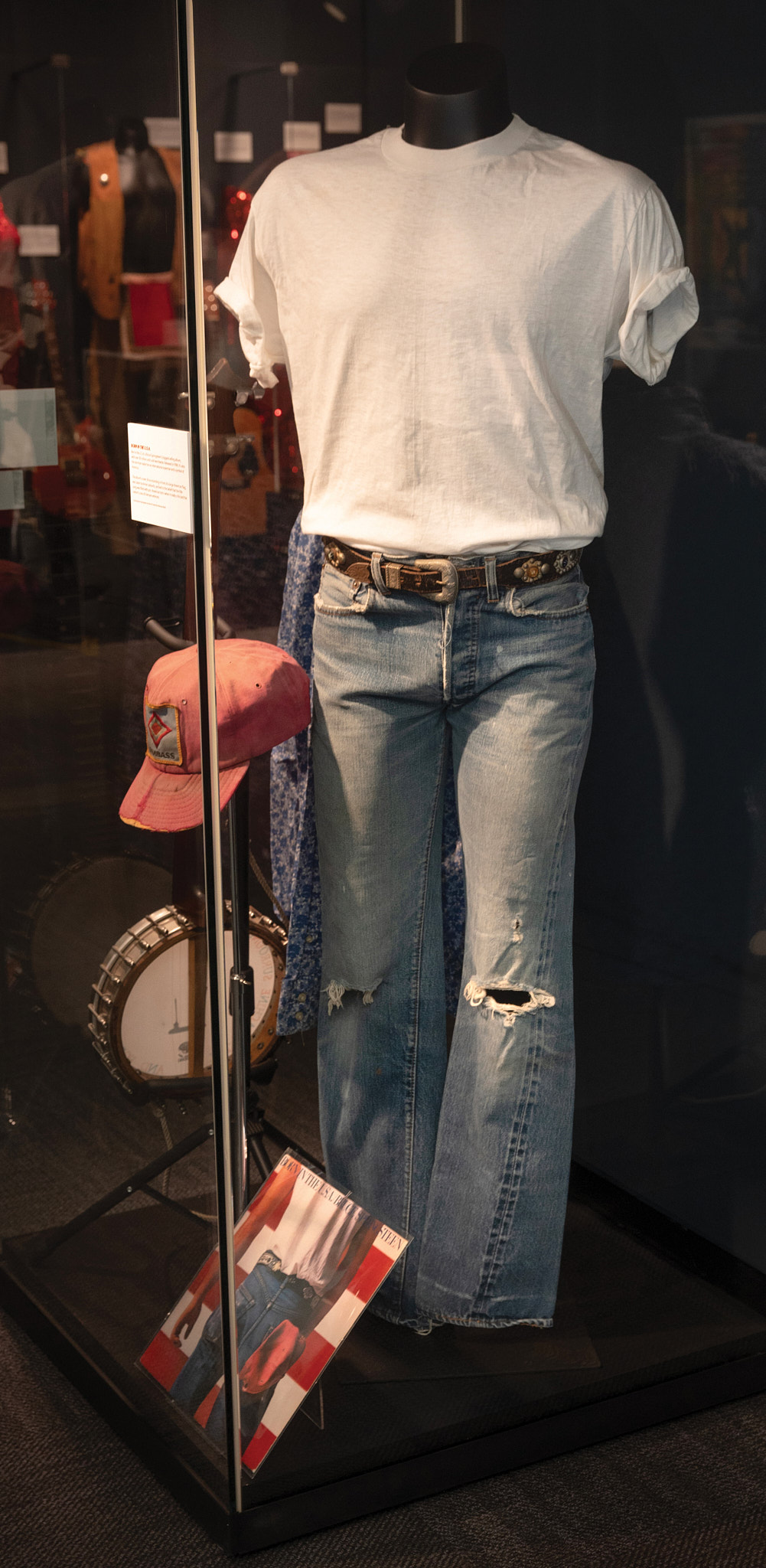

It is hard to quantify the sense of reverence felt perusing the artifacts. Even for visitors with only a passing interest in music, there will likely be an object associated with a musician they respect. Run-D.M.C’s turntable rests slightly to the right of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Number One” guitar, which itself is next to Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” dress, Tupac Shakur’s plaid coat, and Willie Nelson’s jellybean-esque red guitar. Those objects, in turn, all sit across the aisle from Max Weinberg’s Born in the U.S.A. drum set.

After being seen by millions of fans at distance, these artifacts can now surround attendees—and perhaps inspire new musical creations or acts of creativity. The exhibit feels less so about celebrity worship or a simple celebration of stuff; instead, it allows the opportunity for connection to relics that were present during moments that resonated with vast swatches of people throughout the history of the nation.

“At its best, if you explore the music of a particular culture, you will learn a great deal about it,” music critic Anthony DeCurtis says in an introductory video for the exhibit. “That’s certainly true of America. The American identity is a big sprawling concept, and there is music for every single aspect of it.”

One of the best parts of the exhibit is that it appeals to two forms of interest in music. The space features both the mechanical history of music and the artiste side of things. You are able to take a glance at a Diddley Bow, a single-string, guitar-like instrument historically popular with southern Black Americans. And you can check out the homemade guitar of Bo Diddley, the iconic musician who influenced the likes of Buddy Holly, Elvis, the Clash, and more.

“I hope this one-of-a-kind collection will give visitors a deeper appreciation of the role music has played in the broad sweep of American history and encourage them to reflect on the LBJ era, a period of incredible cultural and artistic change,” LBJ Library Director Mark A. Lawrence said in a press release. “These iconic objects will bring that transformation to life and transport us to another time period, as only music can.”

The exhibit ends with a provocation to reflect on what the next 250 years of music may look like. As you think on that, however, be happily forewarned that you may also leave with “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles stuck in your head.

CREDITS: Jay Godwin/LBJ Library (6)