UT Prepares for the Total Solar Eclipse

As her husband drove through southeastern Wyoming’s rolling hills, Martinique Pautzke studied an eclipse map on her phone. Then she peered at the truck’s GPS and looked up. “Let’s take the next exit.”

It was Aug. 20, 2017, the day before a total solar eclipse would sweep across the country from Oregon to South Carolina. Justen and Martinique Pautzke had driven 940 miles north from their home in Fort Davis, where they both worked at the McDonald Observatory, to find an eclipse-viewing spot in the path of totality, where the sun would be completely covered by the moon. At last, they were close to the centerline of that path, in Glendo, Wyoming, population 205.

At the bottom of the exit ramp from Interstate 25, a man greeted them and pointed down the street, where a second volunteer waved them into a field full of cars and RVs. Portable toilets stood along the fence, and a table was piled high with eclipse safety glasses. The field had a convivial vibe as people milled about, buying commemorative T-shirts and visiting.

The next morning, Tricia Berry set up shop outside Barb’s Bounty Restaurant, Jams and Jellies in Chester, Illinois. Berry, the executive director of UT’s campuswide initiative Women in STEM, had reserved her parking spot weeks in advance. She’d flown to her native Illinois and caravaned to Chester, in the path of totality, with some friends and everyone’s children in tow. Together, they unpacked their kid-friendly scientific equipment: a thermometer they’d use to measure how much the temperature dropped during totality; and a colander and slotted spoon they’d hold over white paper to watch the eclipse indirectly, as the light passing through the holes formed crescent-shaped shadows.

Outside Salem, Oregon, Steven and Keely Finkelstein, professors in UT’s department of astronomy, sat on a hill at a relative’s farm. They and their son, Kieran, 7, donned protective eclipse glasses. For their 4-year-old daughter, they had flattened a pair of the glasses and affixed them to a paper plate, cutting holes for the lenses and a pie-shaped opening to accommodate her nose and mouth. It was easier for little hands to hold the plate, eliminating the chance that Maisie’s glasses would slip off at a dangerous moment.

At 10:17 a.m. in Salem—11:45 a.m. in Glendo, 1:18 p.m. in Chester—the moon finished its slow creep across the sun’s face and covered it completely. From their hilltop perch, the Finkelsteins watched as the moon’s shadow swept up the slope until it enveloped them. Steven Finkelstein removed his glasses and was stunned at the brightness of the corona, the hot gases of the sun’s outer atmosphere that normally aren’t visible amid the brightness of the sun itself. In Chester, the cicadas stopped chirping and a slight breeze stirred the summer air. Berry turned slowly in a circle, taking in the 360-degree sunset on the horizon. Overhead, stars emerged in the darkened sky.

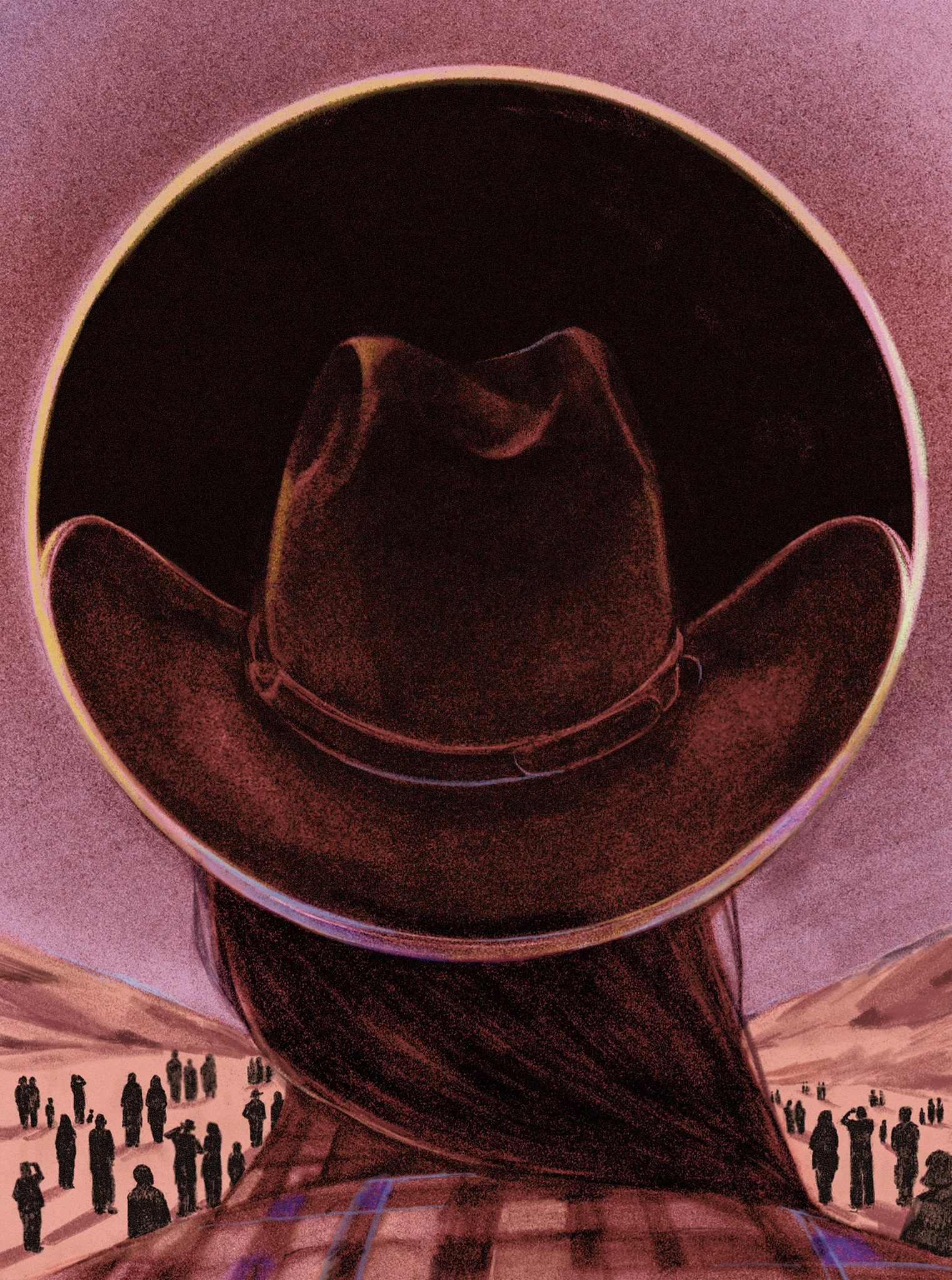

To Pautzke, the two and a half minutes of totality felt like a continuous collective gasp. The people around her—some of whom had traveled from Europe to watch the eclipse—stared upward, their silence punctuated by soft murmurs of “wow” or “oh my goodness.” When the darkness began to lift, people spontaneously applauded. “It’s like when people clap in a movie theater,” she says. “There’s nobody there to appreciate you clapping, but we were all just excited and needed to do something.”

An estimated 215 million people watched the eclipse on Aug. 21, 2017. Because of their location, most saw a partial eclipse, visible as a crescent covering part of the sun’s surface and slightly dimmed daytime light.

But those in the 70-mile-wide path of totality, where the moon completely covered the sun, experienced the mystifying sensation of midday darkness. The moment it was over—after travelers drove home through massive post-eclipse traffic jams—newly minted “eclipse chasers” began making plans to see the next one.

That next solar eclipse will occur in the early afternoon of Monday, April 8, when the path of totality will cross the country from Eagle Pass, Texas, to Monticello, Maine. The entire eclipse will last about three hours, as the moon slowly crosses the sun, briefly covering it completely. Most of Austin—all but the southeast reaches of the city—will experience close to two minutes of totality. Farther west, at the centerline of totality, Fredericksburg and Kerrville will see nearly four and a half minutes of darkness.

Such towns are preparing for an influx of visitors from all over the world, possibly enough to quadruple their populations for the day. Hotels and vacation rentals have been sold out for months. Leery of repeating the traffic standstills after the 2017 eclipse, their leaders are encouraging guests to stay an extra day and locals to stick close to home.

In Austin, UT alumni, staff, faculty, and students are doing their part to help the day go smoothly and to encourage Texans to participate in what for many will be a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

“It is actually worth blowing off a whole day of work for this, even if you’re going to be in the car for 10 hours to get somewhere,” Finkelstein says. “It’s worth it.”

The day after the 2017 eclipse, Lara Eakins’ phone started ringing. As the UT astronomy department’s outreach coordinator, she often receives random phone calls from people with questions about the sky. This time, the callers were staff at Hill Country resorts who’d realized they would be in the path of totality in 2024. Astronomy websites were already promoting the next eclipse and singling out Texas for its likelihood of having clear skies in April. What should they be doing now?

Eakins, BA ’94, Life Member, told them she couldn’t commit a UT expert to an event seven years in the future, but, based on yesterday’s heavy traffic, urged them to offer overnight lodging to any astronomers they booked as guest speakers.

“Half of humanity is probably going to be driving to the Hill Country that morning,” she told them. Eakins and her colleagues in the College of Natural Sciences and across campus would soon start talking about how UT itself should handle the eclipse.

Their initial thoughts: Get the word out. People needed to know the eclipse was coming and make a plan to see it—to ensure they didn’t miss a rare and beautiful phenomenon, and to avoid panic and confusion. And UT would need to prepare for thousands of staff, faculty, and students on campus, which lay in the path of totality, to view the eclipse. Advanced equipment wouldn’t be necessary: Although telescopes with solar filters offer a closer look at the sun during the partial eclipse, the average viewer could get the full experience with eclipse glasses.

Safety was another concern, one that Pautzke, a K-12 education program coordinator at the McDonald Observatory, emphasized in virtual training sessions for teachers, librarians, and astronomy club leaders who planned to host eclipse viewings. In the weeks after the 2017 eclipse, ophthalmologists reported visits from patients with vision loss from retinal burns they sustained while looking at the sun without adequate protection. To avoid permanent eye injury, eclipse watchers need to wear safety glasses, or look through a handheld viewer, that meets international safety standards, until the moon fully covers the sun and from the moment it begins to uncover it again.

Part of a host’s responsibility, Pautzke explains, is telling people when it’s safe to remove their glasses and when to put them back on. Anyone working with young children has an extra challenge.

“The rule for kids is to never look at the sun, right?” says Pautzke, who has a 5-year-old. “And then, suddenly, we have this event where the whole point is to watch the sun change.”

To help the littlest viewers safely watch the eclipse, she recommends the paper plate trick Finkelstein used. Teachers and parents can also help kids view the eclipse without looking at the sun at all: anything with a small hole—a colander or even a saltine cracker—will act as a pinhole camera and project images of the sun onto the ground.

Messages about safety and preparation need to reach the 35 million people expected to watch the 2024 eclipse from within the path of totality. To get the word out, the American Astronomical Society assembled a national taskforce to share lessons from the 2017 event. The group of astronomers, science educators, and emergency planners has led workshops to help community leaders explain the mechanics of eclipses and think through all potential eclipse-day scenarios.

The taskforce includes Pamela Gay, MA ’98, PhD ’02, a senior scientist at the Planetary Research Institute who develops software to support citizen science projects and hosts podcasts and YouTube shows that engage laypeople in astronomy.

Many of Gay’s fellow taskforce members have seen eight, 10, 12 total eclipses—yet clouds or rain have stymied her past attempts. Technology, she says, can come to the rescue.

NASA will livestream the eclipse, and Gay will contribute to The Weather Channel’s coverage, making it accessible to people who encounter bad weather, who live outside the path of totality, or whose responsibilities don’t allow them to step outside.

In Austin, the odds of having clear weather on April 8 are good. But with no major science and technology museum—which initiated eclipse planning in several other cities in the path of totality—the city has lagged behind in preparation for the event.

A local science educator named Lucia Brimer, whose company offers astronomy programs for schools and libraries, attended several American Astronomical Society (AAS) workshops. Brimer traveled to Missouri for the 2017 eclipse and returned to Austin motivated to prepare for 2024. Brimer connected with Berry, Eakins, the Austin Independent School District, the Austin Astronomical Society, and the Thinkery children’s museum, among other organizations, and in September 2022, an Austin eclipse taskforce began meeting monthly.

“I wanted to make sure that we had a central place that we could all talk to each other so that we’re not reinventing the wheel,” Brimer says. Multiple groups were planning public events, and the taskforce helped them coordinate. The group discussed eye-safety messaging and other looming questions: Was the Austin airport prepared for a spike in travel the weekend before the eclipse? Were city leaders aware that the eclipse fell the day after the Cap10K race would bring more than 16,000 runners to city streets, and the CMT Awards would bring nearly as many country music aficionados to the Moody Center?

On Nov. 2, Brimer and other taskforce members testified in support of a city council resolution to direct the city manager to “create and execute a plan to support a positive, safe, and inclusive experience for viewing the total eclipse” by February. The city manager’s work would include raising awareness about the eclipse and the need for eye safety; designating parks for public viewing areas; and using the emergency text-message system to send alerts in multiple languages reminding the public that the sky will darken in midday. Brimer says Austin should have developed a plan at least a year in advance, as it does for major events like the Austin City Limits Music Festival and South by Southwest.

“But I’m really glad the city’s involved now,” she says. “I think they can still do it.”

As 2024 began, organizers entered the home stretch of eclipse planning. Brian Mulligan, PhD ’18, who teaches astronomy at St. Edward’s University, began organizing a public eclipse viewing on the St. Edward’s campus. Margaret Baguio and Celena Miller, who coordinate education and outreach at UT’s Center for Space Research, sent eclipse activity packets and safety glasses to Boys and Girls Clubs that serve more than 5,000 students. Ayla (Jaramillo) Truan, ’10, the assistant superintendent at Garner State Park, organized viewing activities for those planning to camp near the centerline of totality.

And on the Forty Acres, pieces fell into place for UT’s event, the Total Eclipse of the Horns. During the entire solar eclipse, which lasts from about 12:17 p.m. to 3 p.m., student volunteers from the College of Natural Sciences will staff viewing stations scattered across campus. Each will be equipped with burnt-orange eclipse glasses, and some will have telescopes with solar filters. For people with visual impairments, some stations will offer LightSound devices, which emit a musical tone that changes as the light intensity evolves during an eclipse.

The next total solar eclipse visible in the contiguous U.S. will be on Aug. 23, 2044. Austinites have even longer to wait for a solar eclipse visible locally; that won’t happen until 2343. What’s more, Finkelstein says, the moon is very slowly moving away from Earth as its orbit enlarges, at a rate of about 1.5 inches per year. In the very distant future—millions of years from now—it will be too far away to cover the full disk of the sun. Total solar eclipses will cease to exist for earthbound observers—all the more reason to catch this one.

“It’s unlike anything you have ever experienced,” Berry says. “You’re in a parking lot with people from all over the world, who are all there to experience this super-cool thing together, and there’s just something magical about that.”

How to Have a Rewarding Eclipse Experience

- Check eclipse2024.org/eclipse_cities/statemap.html to find the path of totality. The entire area inside the path will experience a total eclipse; locations closer to the centerline will experience a longer period of darkness.

- If you plan to travel, arrive early and stay late to avoid post-eclipse traffic. Plan your food, water, gas, and bathrooms in advance.

- Obtain eclipse glasses that meet the ISO 12312-2 international standard. Some public libraries offer glasses. You can order your own from AAS-recommended suppliers at eclipse.aas.org/resources/solar-filters.

- If you have small children, talk with them about eye safety before eclipse day. Cut holes in a paper plate for eclipse glasses and your child’s nose and mouth and affix the glasses to the plate. You can add an extra layer of safety by attaching an elastic to turn the plate into a viewing mask that’s securely wrapped around your child’s head.

- Most cameras and phones won’t take good photos of the eclipse, and some can be damaged by the sun. Instead, consider setting your phone to record video of your group as you experience the wonder of the eclipse, and buy a professional photo afterward.

CREDITS: Illustration by Ūla Šveikauskaitė; Emily Howard/McDonald Observatory; Aubrey Gemignani/NASA; courtesy of Steven Finkelstein; NASA