Good Reads Q&A: A Writer and Photographer Team up to Tell a New Story of Wild Beauty

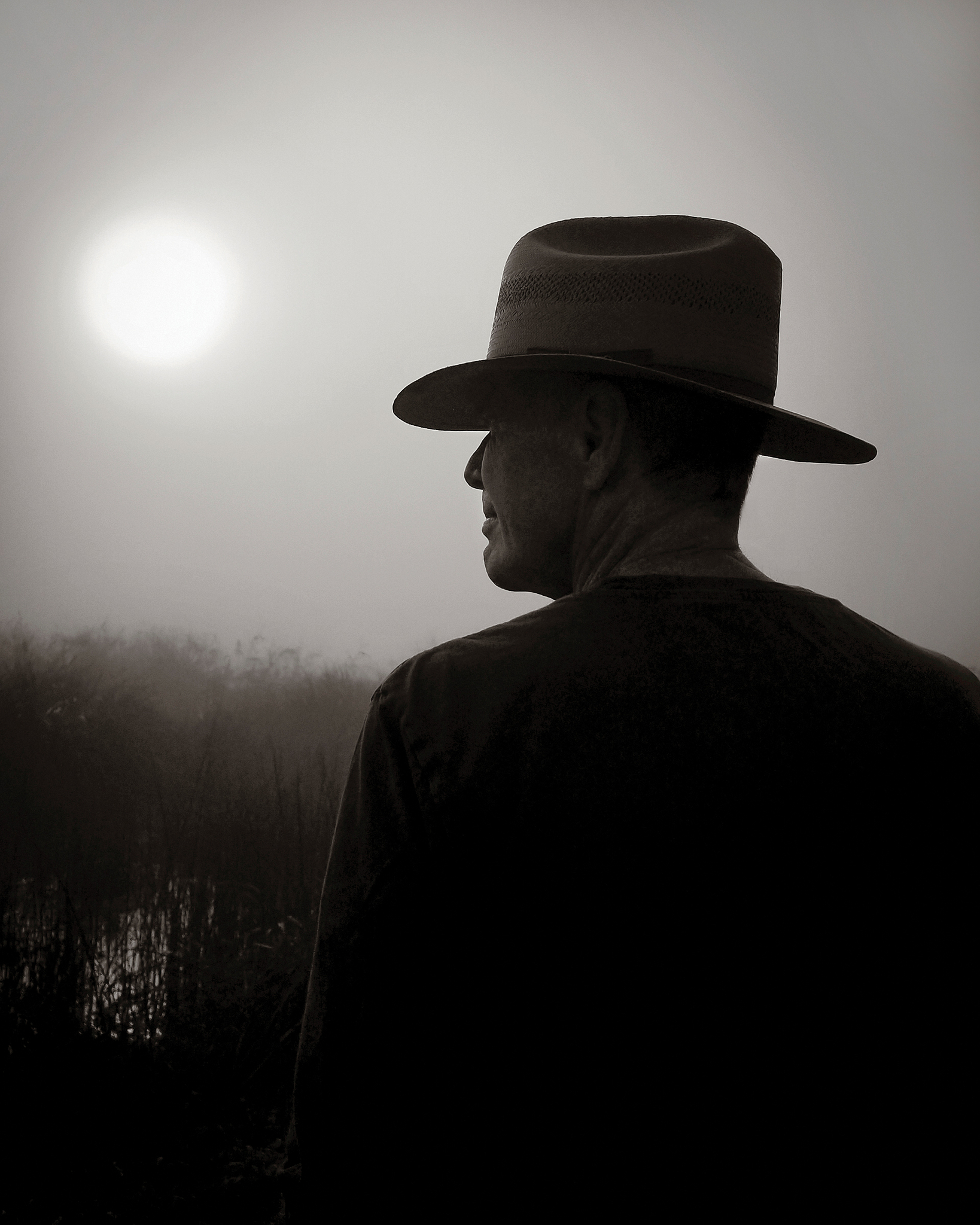

Swamps aren’t generally considered the most beautiful landscapes—but a new book from the University of Texas Press aims to change that perception, with the help of photographer Keith Carter and writer Bret Anthony Johnston.

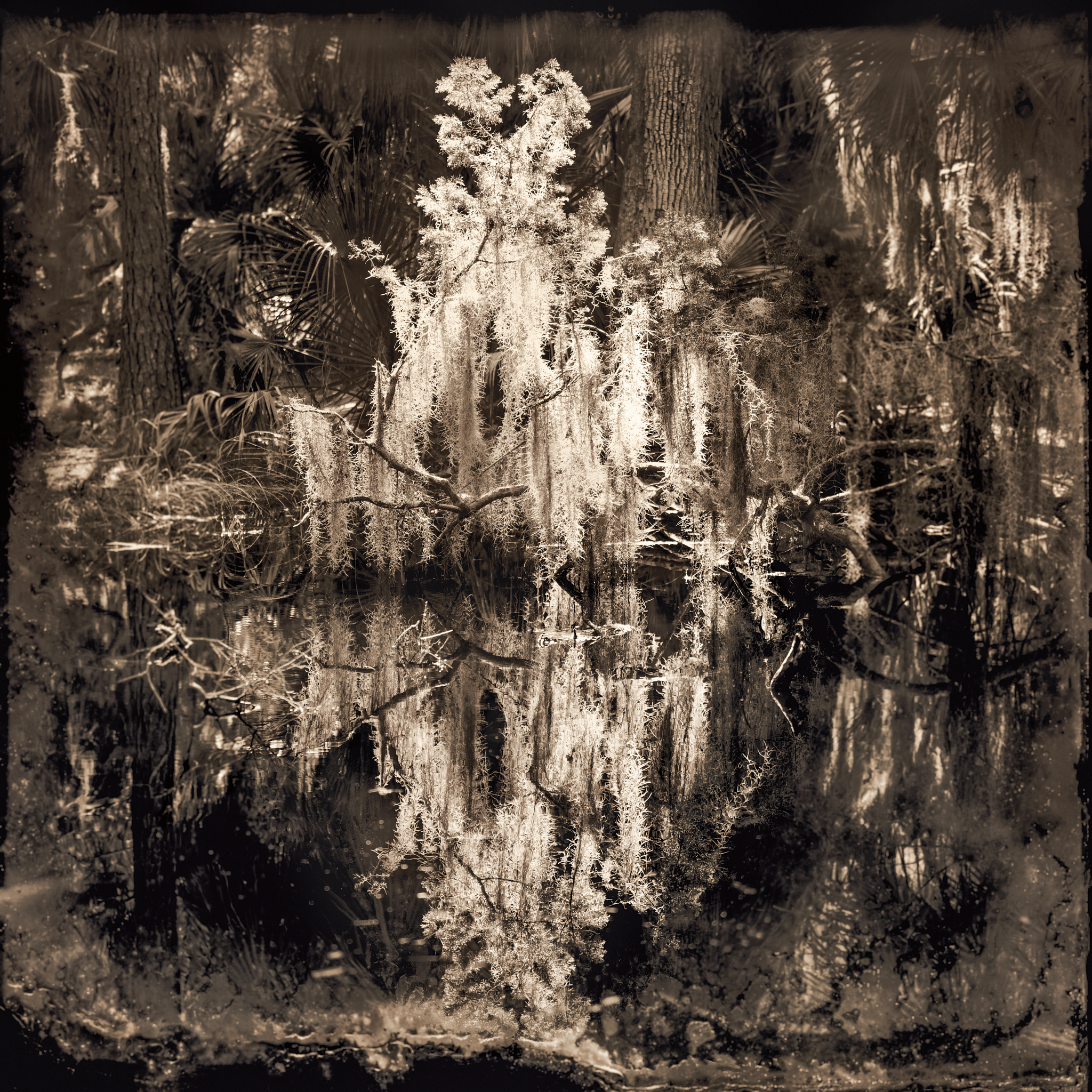

Ghostlight presents work from Carter, a Beaumont native who grew up in the bayous of the area. The photographs were taken over the course of several years, using a mix of contemporary and traditional techniques to capture the area’s landscapes. The result gives the photographs an eerie feel—telling the stories of the wetlands, imperfections and all.

More than just a collection of photography, Ghostlight features a short story written by Johnston to kick off the book. Johnston, a bestselling author and the director of the Michener Center for Writers at The University of Texas, pulled inspiration from Carter’s images to weave a haunting, surreal ghost story.

The Alcalde caught up with Carter and Johnston to talk about their experiences working on the book.

Bret, how did you get involved in this project?

JOHNSTON: Keith Carter is one of the most important living photographers, and I’d long found his work inspiring. When Casey [Kittrell, the editor-in-chief of UT Press], invited me to write an introduction to Ghostlight, I was certain he’d sent the invitation to the wrong person.

When I said that, instead of a typical introduction, I’d like to write a story based on the images, I thought there was no way he and Keith would go for it. But here we are. They gave me an astonishing gift, and I’m sure they regret it more every day.

What was your process like for coming up with this story? Keith mentioned he sent you some photos—were there any in particular that inspired you?

JOHNSTON: Each of the photos evoked a whole novel in my imagination; the hardest part of the process was trying to choose between all the extraordinary images. In my mind, Keith is one of our finest storytellers. His language is light. His syntax is shadow.

Do you feel like the photos had a cohesive story when you first saw them, or did you have to piece it together yourself?

JOHNSTON: The photos tell an amazing story on their own—thousands of amazing stories. What I tried to do was pay such close attention to the images, empathize with the subjects, and follow them toward whatever awaited. I’d never written a ghost story before, had no intention of writing one at all, but the photos had other notions. I did my best to get out of their way, and in the end, no one was more surprised—or haunted—by the story than the writer.

How does this project stand out for you among other work you’ve done?

JOHNSTON: I’m immensely proud of the story, if only because Keith found something to like in it. I sent him a draft before anyone else because if he hated it, I would’ve trashed it and started over. But he sent me one of the kindest, most meaningful responses that my work has ever enjoyed.

This was also the first time that I’ve made a story in response to imagery. I’d thought that might make the process easier, but when you’re responding to work by Keith Carter, the stakes are exponentially higher. In the end, though, the photos focused and liberated my imagination. Whatever the story achieves, it’s because of Keith’s eye and heart, his craft and care.

Keith, you mentioned you used a lot of different processes for taking the photographs. Can you tell us more about that?

CARTER: I used film, and I used historical processes called wet plate or collodion photography. They’re commonly called tintypes, and that means you coat them with some nasty chemicals. If you’re in the swamp, you do it on the spot. And you put it in a great big camera that weighs as much as I do. I used an antique 1880s lens because they have a different look altogether. They’re not aligned like contemporary lenses.

I used antiquarian equipment when I could, and then I used contemporary digital media when I couldn’t. So I used pretty much everything I’d learned in the last 50 years in terms of technique to make these photographs.

One of the beautiful things for me about the historic processes is all the aberrations rather than the perfections. The digital world is all about perfection, and the historic world was more robust for my way of thinking and to my eyes. I tried to combine the two in this project, and I’d not seen that done. Nor had I seen what I wanted to try and do here really done—the murkiness, the whole surrealness of these beautiful places that nobody really ventures into.

You grew up in the bogs of East Texas. What was it like revisiting them now and capturing them in photos?

CARTER: I’m a different man at a different stage of life now. I look at these areas with an eye that contains all the books I’ve read and all the artwork I’ve looked at over the last 50 years. They’re not, by conventional standards, “pretty” photographs or pretty places. They require a different sensibility. I think they’re beautiful, but that’s different from pretty.

How does it feel for you to have your photographs brought to life in Johnston’s short story?

CARTER: Well, I think it’s an absolute miracle, even in this day and age, when a book comes out. For me, it was like a small dream come true. My projects evolve out of how I live, where I live, who I live with, and the history of those places.

[Bret’s story is] exactly the book I wanted to do and the project I wanted to do. It was narrative; it was cinematic; it was historical, and it’s esoteric.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

CREDITS: Keith Carter; Courtesy of Johnston; Cathy Spence; Keith Carter