Larry Mayo’s Degree Was a Lifetime in the Making

Surrounded by books in a home nestled among the Piney Woods of Lake Palestine in northeast Texas, a 79-year-old former journalist in failing health was doing his homework. With the help of his wife Nancy, BA ’67, who often transcribed dictations or his increasingly illegible handwriting, Larry Mayo labored away on the final assignments required to graduate.

Sixty-two years after he walked onto the Forty Acres, he was completing his college degree—thanks to Nancy’s encouragement and the rediscovery of a yellowed letter from UT’s dean of the communications school in 1972 suggesting he finish what he started.

Larry put it this way in one assignment: “The unfinished attempt to graduate remains a dangling participle in my long, happy life. I want ‘UT Graduate’ chiseled on my headstone.”

But the couple’s collaboration started long before then.

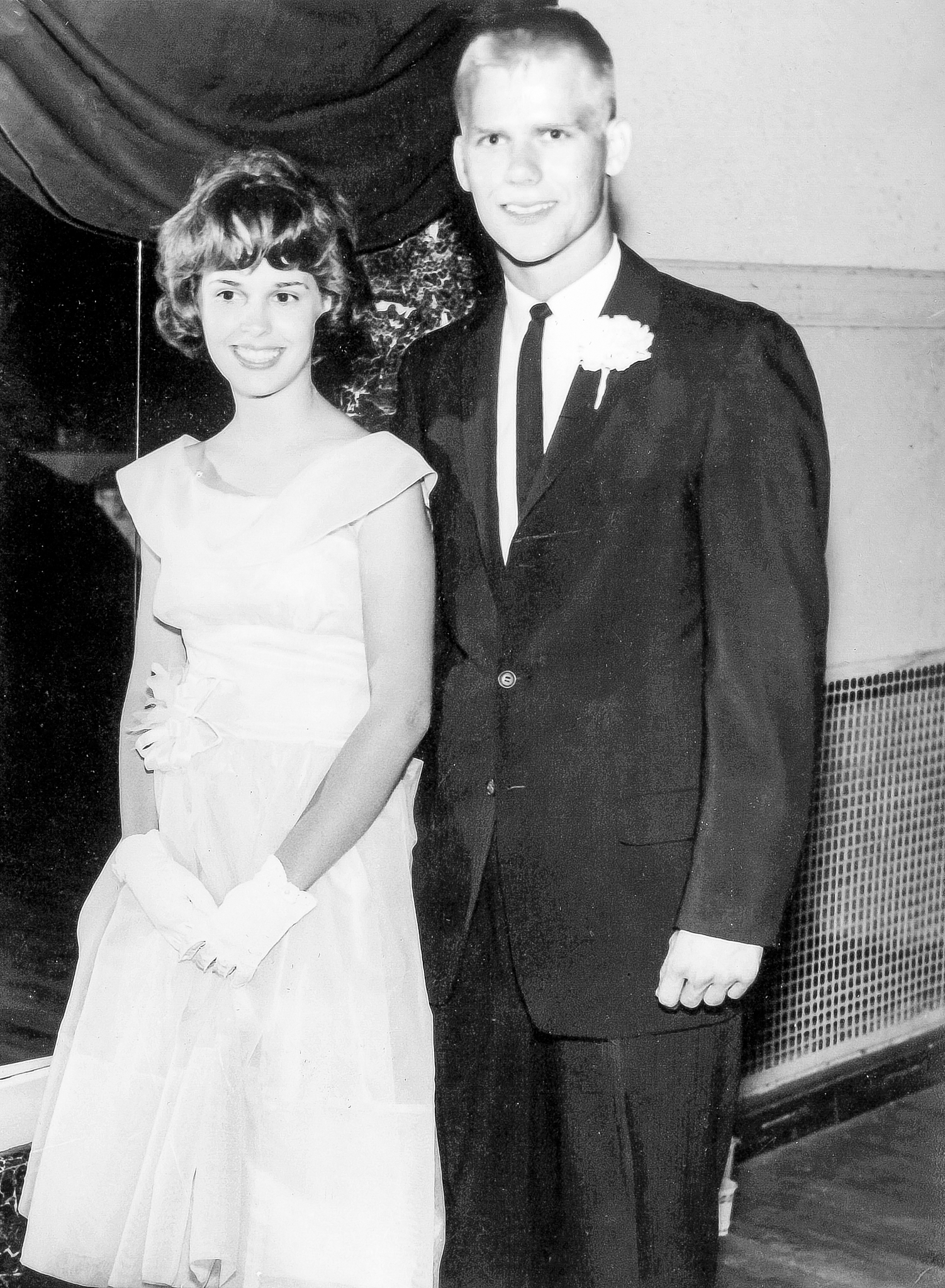

Larry always remembered the day he met Nancy. They were both students at Sherman High—he was a senior and class president, welcoming students to a school assembly alongside the principal. In the front row were three sophomore girls, one wearing braces and a black and white dress with a white piqué collar. He thought to himself, I wonder what it would be like to kiss a girl with braces.

Larry and Nancy would “go steady” for the rest of his senior year (even though she got her braces off before their first date). They each reserved pages in the front of their yearbooks and wrote page-long notes to each other before Larry left for college, and they broke up.

His ambition to attend the Air Force Academy—with an appointment by the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives at the time—was abruptly halted when Larry failed the pilots’ physical, discovering with surprise that he had been colorblind his whole life. At his father’s urging, Larry enrolled at Arlington State, a nearby commuter college, to study electrical engineering. But after three semesters (and a largely unsuccessful job he took as an electro-mechanical draftsman to put himself through school), he transferred to The University of Texas at Austin to study journalism, paying his own way with all of $316 to his name.

He joined the staff of The Daily Texan to report on campus events and Longhorn football. His biggest scoop—“ill-gotten gains,” he later wrote in an assignment for his final credit—occurred on the day of the 1966 Tower shooting. Larry was sheltering in place on the second floor of the communications building when he heard on the radio that police had killed the perpetrator and would be bringing the body out of the west entrance of the Tower.

Taking a risk, Larry took his Argus C3 35-millimeter camera to the Tower’s north entrance instead, where he waited alone. Soon, four uniformed officers emerged with a body on a stretcher covered by a blue blanket.

“As they stepped through the outer door, the blanket slipped,” Larry recalled. “I took [one of] the only picture[s] of Whitman taken that day.”

He quickly crossed the mall and dropped the film at the Texas Student Media photography lab. He had just reached home when he got a call urging him to return to the lab right away: The Associated Press was interested in his pictures. He sold the photo to AP for $600, and eventually to European outlets in Germany, Italy, and France, which helped cover overdue bills, back rent, and another year of classes.

But soon even this boon ran out, and Larry needed a job. He was 25 years old—and hopeful he had aged out of the draft for Vietnam. Employers, however, were wary of hiring someone classified by the military as 1A: “available for military service.” Unable to afford tuition and costs of living, he dropped out in 1967, just three hours shy of graduation. Larry moved home and started a weekly newspaper in a Dallas suburb; The Lancaster Leader quickly grew in revenue and readership.

“We were on the verge of going from a controlled distribution (free) paper to a subscription paper,” Larry wrote. “Then the army decided old soldiers were better than no soldiers.”

Newly married to his first wife, he reported to basic training in Fort Polk, Louisiana, where he was assigned to produce the base’s newspaper, The Ft. Polk Outpost (affectionately referred to as “The Ft. Polk Outhouse”). The job was a piece of cake, he said, even allowing time to fish when not with his wife and son.

That pace ended when, with only nine months left in his tour of duty, Larry was sent to Vietnam.

“Upon arrival, I was given another ugly haircut and assigned to a mine clearing company,” Larry wrote. “My main goal [in Vietnam] was simple: Stay alive. This assignment was contrary to that goal.”

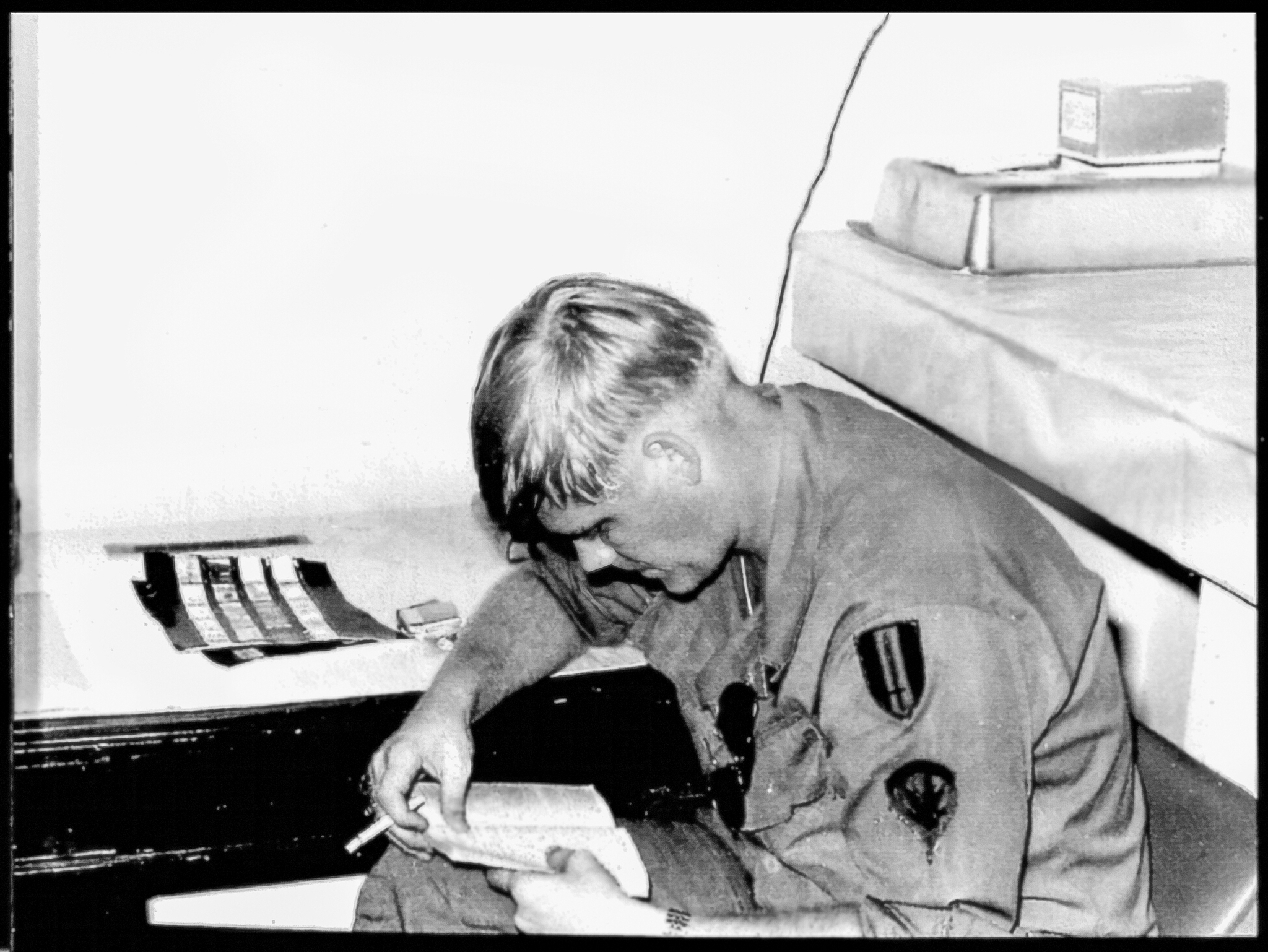

He traveled to the Army’s headquarters there in the summer of 1969 to search for a safer job. In the mess hall, Larry met Captain Baker, who saw his value as a wordsmith. Baker was an editor for The KYSU’ (a Vietnamese word for “engineer”) Army magazine, but he was rotating back to the States within the month.

Larry was reassigned that day. As editor, he enjoyed an unlimited budget and monthly expeditions to Tokyo, where he worked on the full-color, glossy publication with artists and production assistants at Dai Nippon Publishing, then Japan’s largest printing company. He would go on to supervise some 250 correspondents and photographers, earning the Bronze Star Medal and the Army Commendation Medal.

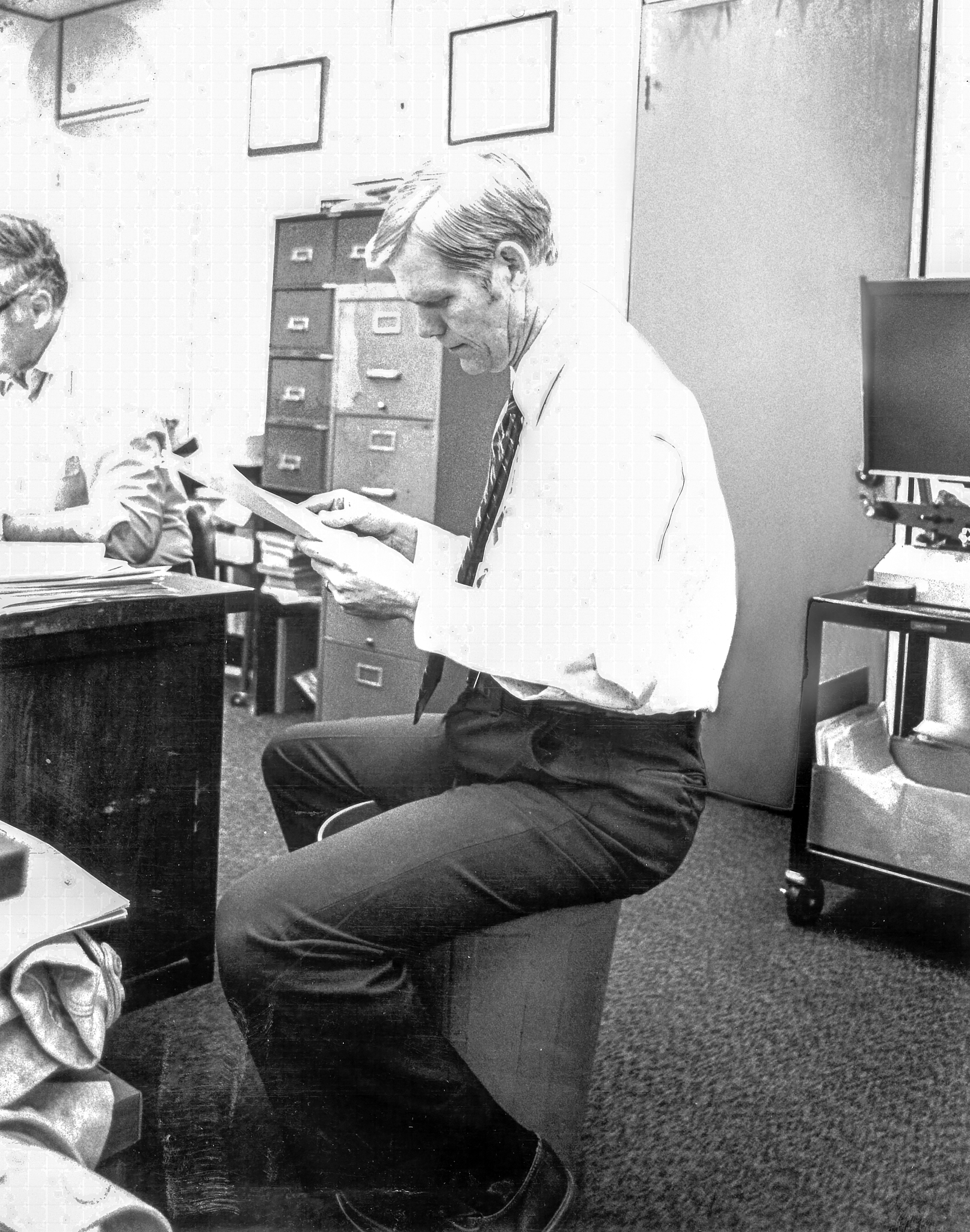

After returning from the war, Larry continued his journalism career, for several years at the Dallas Times Herald before moving with his family to East Texas in 1977 as the business manager and eventually editor and publisher of the Palestine Herald-Press. Around the same time, Nancy had moved with her then-husband just 30 miles east to Tyler.

Nancy’s husband, a doctor, heard from a patient that an old boyfriend of hers was publishing newspapers in Palestine. Other than a chance meeting in front of Hardin House while they were both undergrads, Larry and Nancy had never reconnected. Despite their proximity and history, she didn’t think to reach out.

“Larry Mayo never crossed my mind for the next 11 years,” she says.

Over the next decade, Nancy raised three children before divorcing. As a new financial advisor with PaineWebber, she took a seminar on building a business in small towns. That’s when thoughts of her high school sweetheart resurfaced, and she reached out for advice on potential clients.

The call led to a meeting in his office at the Herald-Press in June 1988, where they talked for five hours. While his voice sounded exactly the same, she says, he now had two sons and significant leadership in his community, with many seeking his advice on local and state politics.

Five months later, his father died, a memento mori of sorts, reminding him that life was short. Two years later, after their respective divorces were finalized, they were married.

Nancy and Larry lived apart for the first 11 years of their marriage, maintaining careers and raising children. Before retiring, Larry had served as publisher for the Herald-Press for 27 years, in addition to managing approximately 15 additional local papers at the time of his retirement—and all without a degree.

Through it all, Larry never forgot those unfinished hours of coursework. Before being drafted, he had devised an independent study to finish his degree, but his advising professor was no longer with UT when Larry attempted to restart the project in the ’80s.

Several decades later, in 2005, he contacted his friend Mike Quinn, a renowned professor in the journalism department who agreed to help, but Quinn passed away in January 2006. Larry’s effort once again stalled, and the dean’s 1972 letter remained filed away.

While combining households, Larry and Nancy were going through old boxes when she found the letter and urged him to reconsider the opportunity.

“At first, I think he wasn’t sure he could do it,” Nancy says. “I knew he could.”

Larry sent a copy of the original letter to then-dean Jay Bernhardt, along with a note: “I won’t burden you with a long explanation for the tardiness of my response; however, the excuse involves financial embarrassment, Vietnam conflict, work, marriage, children, career, and simple procrastination. I now find myself, in the late innings of my life, wanting to identify myself as a Texas Ex.”

And so began the process of tracking down transcripts, vaccination records, and the ephemera required to re-enroll. He didn’t even consider taking the class at nearby UT Tyler. It felt important to Larry that it be through the flagship campus.

“He didn’t want his obituary to say that he ‘attended The University of Texas,’” Nancy says. “He wanted it to say he graduated from UT Austin.”

Working closely with Cassandre Alvarado, BJ ’95, MEd ’98, PhD ’04, associate dean for undergraduate education in the Moody College of Communication, Larry completed his degree in an independent study, which he conducted online, on applied ethical leadership in newsrooms.

“We had as much to learn from Larry as he had to learn from us,” Alvarado says. “For me, it was a matter of trying to design a course that took advantage of his strengths, but also gave him an opportunity to have a meaningful capstone experience.”

In one of his assignments—an annotated autobiography—Larry credited Nancy with helping him finally achieve what he had unsuccessfully attempted at least four other times.

“I would not be able to complete [my degree] without the determination of my wife Nancy to help me navigate college today,” he wrote. “She has no quit in her character.”

Only a year after officially graduating, Larry Mayo passed away on June 10, 2023, at age 80.

After a weekend spent at the family farm where Larry had built a house out of a decommissioned boxcar, Nancy kissed him goodbye and headed home, leaving Larry to lock up before a storm rolled in. A few hours and four missed calls later, Nancy decided to drive back for him. She was met at the boxcar by the sheriff and EMS, and she knew then that he was gone. He’d had a massive heart attack resulting in a fatal head injury.

On June 30, 2023, the chapel at Eagle’s Bluff was at capacity for Larry’s memorial service. All five of his children and stepchildren spoke, remembering him fondly for his omnivorous reading, gourmet cooking, and of course, his school spirit.

“One of the things that remains true about UT is that it is a transformational place, and that was evident from Larry’s experience here,” Alvarado says. “This place is filled with faculty and staff who believe deeply in the power of education to transform lives—and believe that is a lifelong journey.”

Alvarado calls it an honor to have seen Larry through the end of his journey; Nancy, a privilege.

“I know him better now than I knew him in all those years,” Nancy says. “I see the more complete picture.”

Illustration by Ūla Šveikauskaitė

CREDITS: Courtesy of Nancy Mayo (3)