Writer John Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor Home Extends the Forty Acres

It was a foggy morning in February 2021, and Kathryn Szoka was flipping through the New York Times from her home in Sag Harbor, New York, when her sacred Sunday routine was shaken by one announcement: John Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor home was on the market. The asking price was $17.9 million—a figure that only made Szoka’s heart sink further. As a longtime Sag Harborite and co-owner of the town’s bookstore Canio’s, she feared Steinbeck’s summer home and creative haven would be razed to make room for one of the McMansions that had popped up in the fishing village over the years.

“I was shocked and disheartened,” Szoka says. “Reading about it in the dead of winter, in the middle of [the pandemic], at the breakfast table, made the potential loss all the more disquieting. And, the need to act, all the more urgent.” Days later, she launched an online petition, asking others to help save the property where Steinbeck famously penned his final novels.

In March 2023, more than two years after news of the listing broke, the Sag Harbor Partnership—a local nonprofit that joined Szoka in her uphill battle to save the cultural landmark—finally raised the funds to purchase the home for $13.5 million. What’s more, the partnership agreed to lease the property to The University of Texas’ graduate MFA program, the Michener Center for Writers, which will use it to house novelists, playwrights, and poets as part of the Steinbeck Writers’ Retreat launching this September.

“At first, nobody really thought it would happen,” Szoka says. “I was the person who really got the ball rolling, so it’s great not to feel like Sisyphus. We got to the top and we stayed there … and now Steinbeck’s house will outlive all of us.”

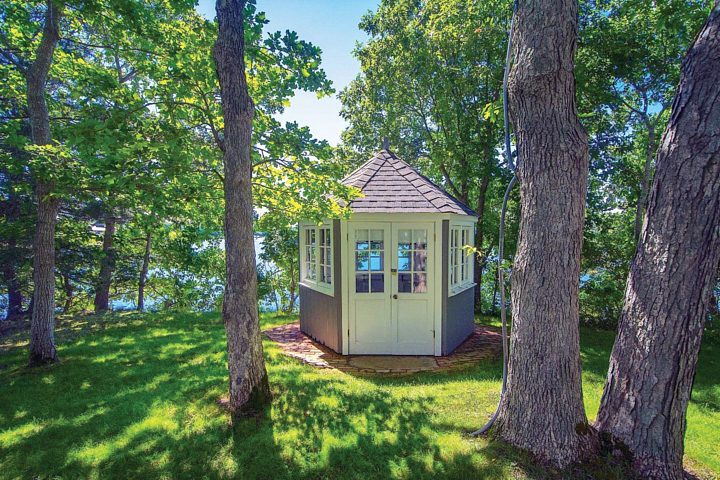

With her penchant for community activism, Szoka was determined to raise awareness about both the rich literary history and local significance of the property. The tree-spotted 1.8 acres is home to Joyous Garde, Steinbeck’s writing gazebo overlooking the cove, where he was known to draft stories in pencil on a yellow legal pad. His “little fishing place,” as he called it in his book Travels With Charley, provided the perfect respite to write, although Szoka says Steinbeck was anything but reclusive. He was often spotted around town socializing in his fisherman’s cap and rubber boots, and was even responsible for founding Sag Harbor’s annual Old Whalers Festival. Szoka believes the village revitalized his career—inspiring his final novel The Winter of Our Discontent, which is set in a similar fishing town—and she speculates the Nobel laureate would have been thrilled to offer his home in support of the next generation of writers.

But long before the Michener Center’s residency was a gleam in Szoka’s eye, the process of financing this endeavor was nothing short of a Sisyphean struggle. Even as locals nodded their support, Szoka knew she would need to match signatures with cash to really get the project off the ground. So she turned to her friend on the Sag Harbor Partnership board, April Gornik, for help reaching deeper pockets.

With a stated mission of preserving and enhancing the history and culture of Sag Harbor, the partnership was already closely aligned with Szoka’s goals. It also had a history of successfully implementing other large-scale community projects, including its recent purchase and restoration of the historic Sag Harbor Cinema, which burned down in 2016. Gornik set up a meeting between Szoka and Susan Mead, the partnership’s president, as well as fellow board member Diana Howard, JD ’85. She told them about her idea to repurpose the property as a writers’ retreat honoring Steinbeck’s legacy. The partnership pledged its full support, and from there they were off and running, Szoka says.

But one big question still remained: Who would operate the retreat if they successfully bought the property?

“We thought we might be able to help raise the money and purchase the house, but we knew that we didn’t know how to run a writers’ retreat,” Howard says. “So we were looking for a university to partner with us.”

Szoka posed the opportunity to several local institutions, such as Stony Brook University, but none seemed to be the right fit. “I’d gotten really great interest in this succeeding, but very little bandwidth to actually manage a writers’ retreat there,” she says.

A larger university was needed to continually fund the retreat and source writers-in-residency. So, Howard thought to propose her alma mater, The University of Texas, as a potential candidate. She had a connection in UT’s development office, so she reached out to gauge potential interest.

“UT jumped in with both feet,” Howard says. “It seemed like it was meant to be.”

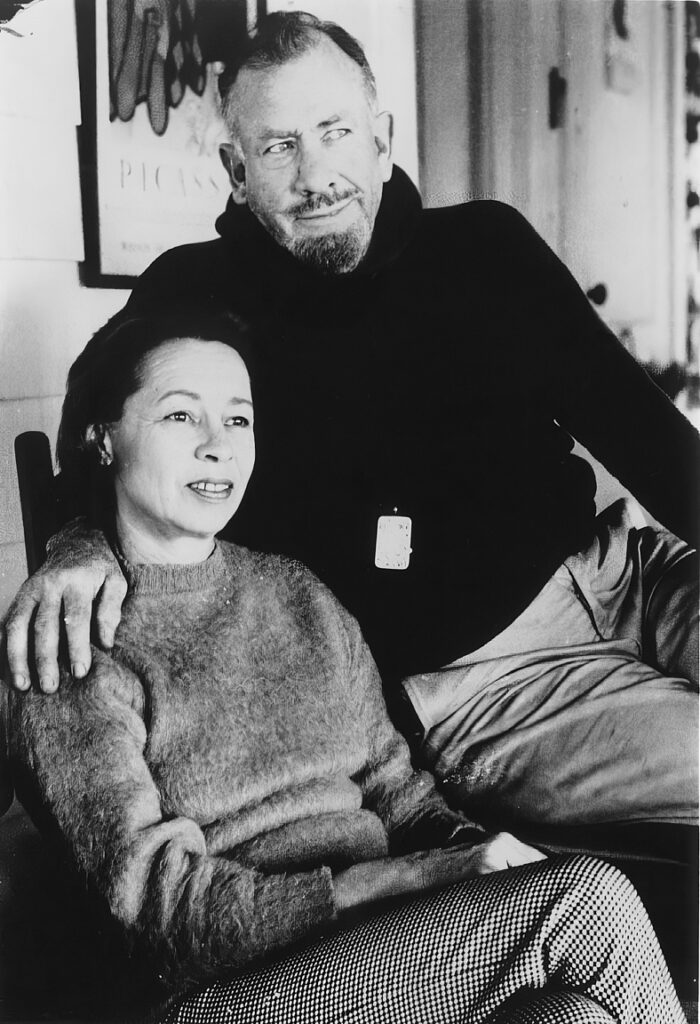

Although UT may seem like a strange choice, given that Austin is hundreds of miles away from Sag Harbor, Howard says a number of synergies emerged between the University, the Steinbecks, and the Sag Harbor community. For starters, Steinbeck’s third wife, Elaine, with whom he purchased the property in 1955 and whose estate later orchestrated its sale, attended UT. The Harry Ransom Center is also home to one of the largest Steinbeck collections in the world—which came to UT through Elaine—including his correspondence with editors, a draft of a nomination acceptance speech he wrote for President Lyndon B. Johnson, and the journal he kept while writing The Grapes of Wrath. Elaine’s heirs, including her nephew Clark Covert, BBA ’76, Life Member, also donated the contents of the home. Finally, a woman on the local advisory board for the partnership had previously lectured at UT’s Michener Center and could vouch for its world class reputation.

The Michener Center is a graduate writing program headquartered in the J. Frank Dobie House on Dean Keeton, which hosts 36 writers at any given time. Though its presence on campus is unassuming, its literary influence is dizzying in magnitude. Since opening its doors in the early 1990s, the program has touted high-profile alumni like Philipp Meyer, a Guggenheim Fellow, Pulitzer Prize Finalist, and author of American Rust; Nathan Harris, author of Oprah’s Book Club pick The Sweetness of Water, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize; and Lara Prescott, New York Times bestselling author of The Secrets We Kept, to name a few.

Michener Center Director Bret Johnston says the center is set apart as the only creative writing MFA program with full and equal funding for three years—something Steinbeck would have likely loved, as he was rumored to have gifted all of his Pulitzer Prize winnings to a struggling early novelist. To top it off, UT had the experience and the funds needed to support the project. They already had a track record running Paisano, a residency headquartered on J. Frank Dobie’s 200-acre ranch southwest of Austin, since 1967. And UT’s development office pledged to put $10,000 toward operating the residency if the sale went through.

With the Michener Center on board, the collective of advocates began outlining plans for the residency to present to the town of Southampton (the larger municipality where the village of Sag Harbor is located). The goal: to secure a sizable donation from the town’s Community Preservation Fund to support the project.

The Community Preservation Fund is raised through a 2 percent transfer tax on high-value homes in Southampton, enabling the town to purchase and preserve local historic properties. Although the Steinbeck house clearly possessed enough historical significance to be eligible for these funds, Howard says a benefit to the community would need to be made clear in order to obtain a sizable investment.

So the Michener Center designed the program to offer three-month residencies to a maximum of three writers each year, leaving the property open for public visitation in the interim. The fall residency is reserved for a graduate of the center, giving alumni the exclusive opportunity to apply and work where John Steinbeck wrote, while the other residencies are allotted to any writers at the apex of their careers, Johnston says. And although the secluded property offers solitude—an integral part of the writing process—the writers-in-residence will also be required to connect with the community by hosting an event in Sag Harbor.

“The writers will of course be alone with their work, but they’re also going to go into the community and do a lecture or stage a play, or they’re going to have a talk about the work in progress,” Johnston says. “We want them to interact with this community because it’s very important to Steinbeck’s legacy.”

To further cement this plan for cultural and literary symbiosis between locals and the Michener Center, Johnston flew up to Sag Harbor in April 2022. He appeared in front of the town board in a hearing to discuss their potential investment, but more importantly, he says, he came to listen.

“I sang the praises of the Michener Center, its staff, faculty, and students, and I expressed what an honor it would be for us to preserve such a tremendous piece of literary history, to carry on Steinbeck’s legacy of generosity,” Johnston says. “Mostly, though, I tried to listen far more than I spoke. I listened to the voices of the village discuss what mattered to them and how a writing retreat would fit into their community and how it might enhance it. We are guests in their community, and I wanted to hear firsthand how we could make our presence useful.”

While Johnston was a guest himself in Sag Harbor, Szoka says he made quite the impression.

“I think Bret just kind of got Sag Harbor … It takes sensitivity on the part of somebody coming into the community to be humble enough to recognize that they have to learn about it. Like how Steinbeck came to listen and observe. I just felt, in my exchanges with Bret, that he had that sort of wisdom,” Szoka says. “Now we just want him to spend more time here.”

As some skeptical community members warmed to the idea of a faraway university moving in up the street, Howard says it became increasingly important to consider their needs as future neighbors. Because Steinbeck’s home is situated on a quiet and narrow family street, they wanted to avoid drawing unwanted traffic.

“People can go visit the property, but we agreed not to list the address [online]. You have to wait until the day before you go to get an email with the address,” Howard says. “I think the reason the neighbors came out to support us was because we were transparent all the way through with what we were doing, what the agreement was, and what the town wanted in terms of a visitation schedule.”

The final local hearing to approve funding was held in February 2023 before the town board. Although many locals and members of the partnership came out to speak on behalf of the project, Szoka says the Steinbeck vote was last on the agenda that day, and the lengthy wait eventually weeded out other attendees (save the attorney for the Community Preservation Fund). By the time the board unanimously voted to pledge $11.2 million toward the purchase, Szoka celebrated the triumph alone, in the dead of winter—reminiscent of the moment she first started her fight to save the home.

“I was so very moved, and each town board member spoke really from their heart about why they wanted to make sure that this happened. They all saw the essential need to do this, not only for the village and the town and the state, but the country and internationally,” Szoka says. “I remember I walked out … and the sky was this beautiful sort of blue. And I drove home just thinking, Wow, I can’t believe that after two years this has finally happened.”

However, because the investment from the town was shy of their goal, the partnership still had a bit more crowdfunding to do. Howard says the remaining funds came from a $750,000 grant from the State of New York, as well as private donations. Less than a month later, the sale was final.

With the property now under the stewardship of the Michener Center, Johnston emailed a memo to alumni, sharing the news and encouraging them to apply for the inaugural fall residency.

“I read the email, and I just thought it was amazing for Michener to have acquired this,” says Lauren Green, MFA ’21, a novelist and poet who graduated from the center. “I think of my three years there as this incredible gift of time that I was given. Regardless of whether or not I get to go to the house, the fact that it’s available, that it’s reserved for people who were in the program, I think just amplifies the center’s generosity.”

Green is the author of the poetry collection A Great Dark House, which won the Poetry Society of America’s Chapbook Fellowship, and her debut novel is set to publish in 2024. At this stage in her career, she says an opportunity like the Steinbeck residency would be invaluable—not only because it offers the resources to step away from daily life, but because of the unique location. She says there’s no question that she will apply for one of the many future residencies.

“I’m a little spiritual in this sense, but I do think there’s something about the space you write in that can seep into the work,” Green says. “The landscape itself is right on the water, under the open sky, where you can cast your consciousness out. Spending time there, experiencing the environment and the culture … can really enhance your writing.”

Johnston hopes that this space, hallowed by decades of literary history, will continue to be a refuge for the next great writers of this age, such as Carrie R. Moore, MFA ’23, a fictionalist and recent Michner graduate who will be the first writer-in-residence at the house this fall. There, Moore will revise a novel she began at UT which examines the long-term, communal impact of sexual violence against Black girls. “I feel enormously blessed to have been able to attend the Michener Center, where no one shied away from writing about difficult topics,” she says. “And I feel still more blessed to be able to write in Sag Harbor.”

“What the Steinbeck House offers is solitude in a very inspiring part of the world … you feel a certain kind of pressure writing in a place like that, but I think that pressure is a privilege,” Johnston says. “Now that this is across the finish line, I think everybody feels a lot of responsibility and a lot of excitement.”

Illustration by Sam Brewster, photos courtesy of Jean Boone and Sotheby’s International/Gavin Zeigler

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.