The Tower’s Beloved History and Renewed Future

Most days, UT President Jay Hartzell approaches his office in the Main Building from the north. There, on the lower floors of the Tower, he sees rows of rusty steel plates, each with a gilded character from the Egyptian, Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, or Roman alphabets, a sign that the University's former main library has seen better days. From his office on the fourth floor, Hartzell points up at the Tower proper and says, “Looking out that window, you can see it every day, and you think, That’s just not right. You're posing for pictures in front of it with people, and you’re thinking. I hope we’re taking this from far enough away.”

Shortly after Hartzell, PhD ’98, Life Member, became UT’s president, he asked Nancy Brazzil, longtime deputy to the president, what seemed like an obvious question: “Why don't we fix the Tower?” He remembers her reaction—a blend of excitement and relief that someone was finally asking. “It’s such a symbol,” he says. “I just thought it was the right thing to do.”

Hartzell was certainly not the first to wonder at the condition of the University’s architectural emblem. Kevin Eltife, BBA ’81, Life Member, is chairman of UT’s Board of Regents. “Over the last several years, as I’ve been on campus for various events, I was really disappointed in the condition of the Tower, as well as the landscaping on the malls that surround it,” Eltife says. Indeed, a 2009 feature story in the Alcalde asked, next to a photo of the rusted exterior, “Is this the shade of burnt orange we want the Tower to be?”

The rusting spandrels between the windows are only the most obvious of the building’s shortcomings. Those working within the iconic structure, including this reporter, know the challenges it presents daily: frequent elevator outages, no hot water. A sign in a third-floor restroom reads: “Only one toilet can be flushed at a time. If the other stall is flushing, please wait until it is done before flushing. Thank you.” There was the raccoon that fell through the ceiling into the office of the vice president for campus operations some years back, the bat found lounging on a couch in the office of the director of media relations, and the annual plague of crickets. A whole other article could be written just on the Tower’s relationship to wildlife.

As ever, it simply was a question of money amid the thousand other pressing needs of the University.

UT’s leaders have always weighed the cost of restoring and updating older buildings against the cost of starting fresh; it’s how the Tower got here in the first place. A 1934 editorial in the Austin American-Statesman summed up the decision to tear down the original Main Building this way: “Old Main building has been unsafe for years, part of it condemned against any use, other portions limited to cautious occupancy by offices that would not require numbers of students on its rickety floors. Old Main building served its purpose ... And who knows but that the $2 million structure with its 14-story tower that will replace the Old Main building will have served its purpose in 50 years, and in turn will be razed to make way for some other greater and nobler house of learning.”

But tearing down this Main Building, better known simply as the Tower, for some “nobler house of learning” was never even discussed. “Never,” Hartzell says. “Not an option,” echoes Eltife. “The Tower is the Tower!” But returning the Tower to a source of pride would not be cheap.

The original estimate was about $50 million. With Eltife’s leadership and the unanimous support of the Board, the Regents committed roughly half, $26 million, to restore the Tower and beautify the malls that surround it. The rest would come from donations raised through a campaign launching this fall called “Our Tower.”

Bob Zlotnik, BBA ’75, MBA ’80, and Marcie Zlotnik, BBA ’83, Life Members, are chairing the campaign. “The Tower is in such a state of disrepair. It’s disgraceful that that’s our symbol of excellence,” says Bob, who remembers visiting the observation deck as a child in the 1950s. “We just felt like it wasn’t representative of what we want Texas to be.”

Marcie adds that beyond being the iconic and historical symbol of UT, “it includes everyone, whether you’re a native Texan, a visitor, or a transplant. It transcends race, sex, color, and whatever college you go to. It really is a unifying symbol.”

“We set it up as a match on purpose because we want involvement from everybody,” Eltife says. “We want everybody to have a piece of this excitement—that we’re doing something for future generations. And for years and years to come, people will come back and appreciate the beauty of the campus and the Tower. Even if it’s just a dollar from a student, we think it’s important that everybody gets involved.”

In the year since the project was announced, the estimate has grown to $70 million with an increase in the project’s scope.

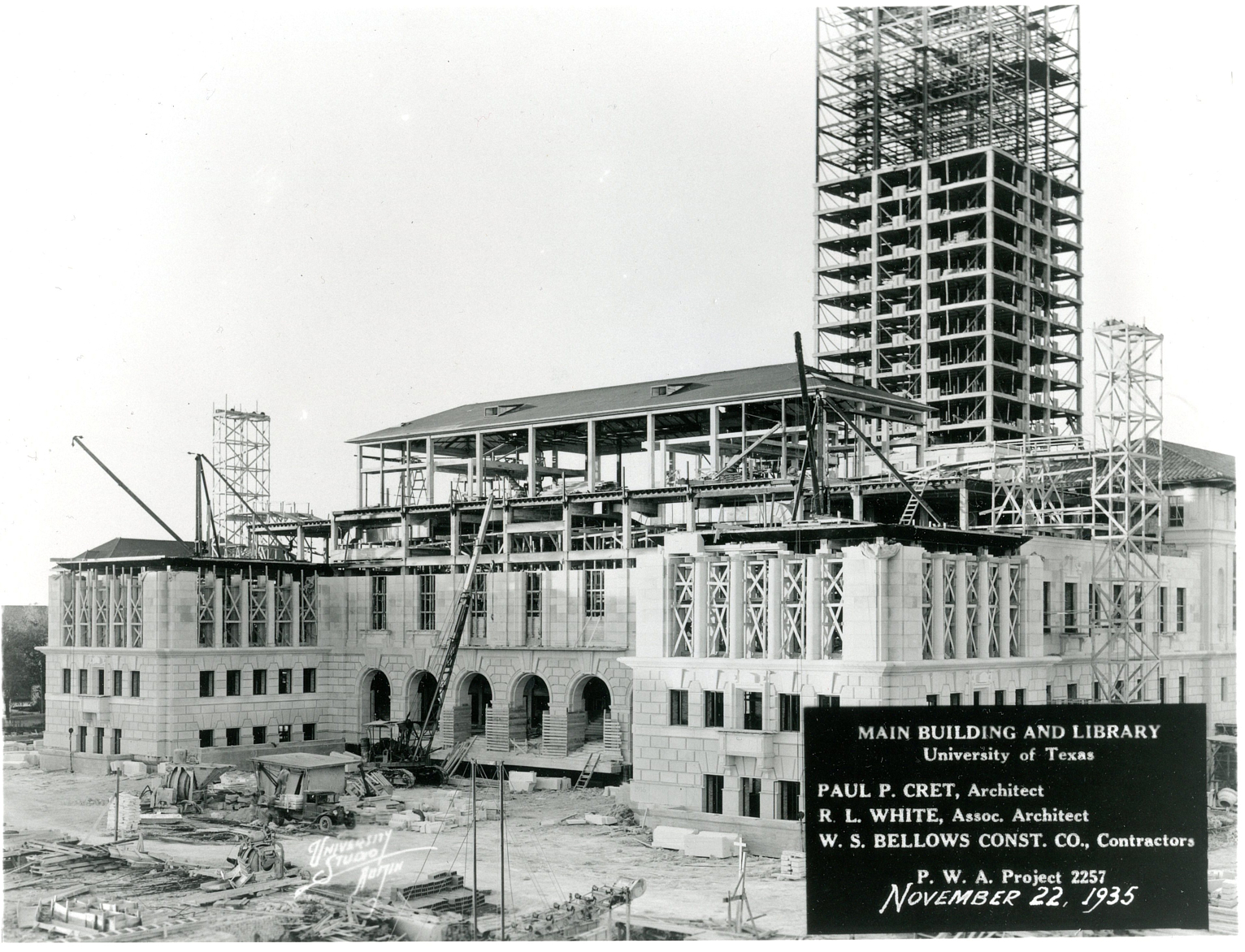

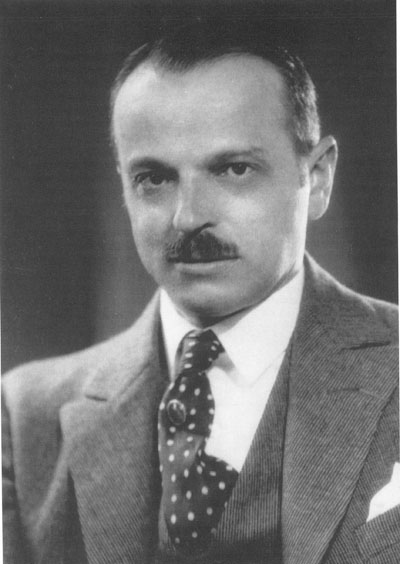

To understand this unique building, how it came to be, and what it really means, we must return not to 1937 and architect Paul Cret, but to 1908 and then-UT President Sidney Mezes.

Towering Aspirations

According to professor and former Dean of the School of Architecture Larry Speck, the real story of the Tower starts with Mezes, whom Speck paraphrases in his emphatic, entertaining way: “Mezes said, ‘We’re not a stupid little college in Podunk! We are going to be a great university, and to do that, we are going to have to have a campus.’ He was bold.”

William Battle, professor of classics and then-chair of the building committee, “bought big-time into that vision,” Speck says, “a big, bold, fantastic campus that would set a mark for what this university was going to be. They were on a mission in that era. They were not timid.” Mezes audaciously hired celebrity architect Cass Gilbert to design a master plan for the campus.

In 1914, Gilbert designed the Woolworth Building in New York, then the tallest building in the world. With skyscrapers on the brain, he began sketching towers in 1916 to replace UT’s Old Main, which, besides being a collegiate cliché, was poorly built and already having problems. Gilbert did many schemes for a new Main Building, according to Speck. “The idea was, now we can do tall buildings, but we also have this history of architecture. How do we merge historical allusions and meaning and fabric with this new capability?”

But the timing wasn’t right. Ultimately, only two buildings designed by Gilbert were constructed: Battle Hall in 1911 and Sutton Hall in 1918. However, their Spanish-Mediterranean revival style inspired much of the look Cret adopted for the expansion of the campus during the 1920s and 1930s. French-born Cret not only designed the Main Building and Tower, but at least 15 other edifices, including Hogg Auditorium, the Texas Union, Goldsmith Hall, and the Texas Memorial Museum.

Knowing Old Main was beloved, Cret proposed a phased, 20-year plan in which the south-facing portion of Old Main would be kept at first, and an E-shaped library would be built abutting its north side, with two large reading rooms on the northeast and northwest and stacks between them. We can see that footprint today in the spectacular Hall of Texas and Hall of Noble Words reading rooms within the Life Science Library, and the stacks—the Tower—between the two. After a few years, Cret thought, when his library had become even more beloved, Old Main would be razed and replaced with a C-shaped building back-to-back with the E to complete the vision. The C would include two more large reading rooms on the southeast and southwest corners, with large reading porches that looked south to the Capitol (even more appealing in a time before air conditioning) and a grand staircase similar to Main’s steps today.

Then, with construction on the E building already underway, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal suddenly made millions of federal dollars available for “shovel-ready” projects. The Regents pounced, and Cret’s gentle, 20-year plan was out the window. The E and the C buildings were both fast-tracked, but, not remotely needing that much of a library yet, the Regents converted the front portion from library space to administrative offices.

“They divided up these beautiful, expansive rooms into a little rabbit warren of offices, and it never worked,” Speck says. “Functionally, it’s a cranky building, because it was severely compromised right from the get-go.” This is why we see floor heights that don’t match up, with steps down and steps up for no apparent reason, further challenging those with disabilities. When you ride the Tower elevator today, you push “8” to get to the third floor. Pressing “1” takes you back to the ground floor, which is not the “first floor.” It’s complicated.

But even with all its quirks, it was a spectacular, monumental building—a hybrid of a Spanish-Colonial main building and an Art Deco tower, capped with a Greek temple. Speck calls it “amazing.”

What few, if any, foresaw was a paradigm shift in the way libraries operate—from closed stacks, in which students requested books at a desk, to open stacks, in which they searched for books themselves. That shift made the Tower’s function as a library short-lived. Indeed, it served less than 30 years as the main library, with the Undergraduate Library (now the Flawn Academic Center) assuming that role when it opened next door in 1964.

When the books were moved out, the Tower portion—with its small footprint, closely spaced vertical supports, and low ceilings—served as unattractive office space for a hodgepodge of administrative departments, though the views were good, and still are. Fire safety issues—there is only one stairway—have prevented it from being fully occupied, and several fires through the years have underlined that danger.

All the while, the exterior of the building aged with as much grace as could have been expected. “It’s a frickin’ phenomenally durable building,” Speck says. “It just hasn’t had any maintenance. Those metal panels are really thick. I mean, it’s a miracle: They’ve done absolutely nothing to that building, and those panels, I’m told, are salvageable. They’re terribly rusted, but they’re not rusted through because it was so well built. But you don’t build a building in the 1930s and expect it to last 100 years without a little paint.”

The Process, the Punch List, and the Timeline

So how will the renewal happen? Every major capital project has someone designated by the president as the project advocate to keep it moving. In this case, that person is Brent Stringfellow, director of campus planning and University architect. He will get input from stakeholders and coordinate daily with working groups focused on various aspects of the project, such as exterior renovation or landscaping. He also will work with Robert A. M. Stern Architects of New York, which has been contracted for the job. An executive committee, probably five people representing different interests, will make decisions about budget and scope and forward those to the president. Ultimately, the Regents will make the final, high-level decisions.

Hartzell thinks of the project in four parts:

First is the exterior. “We knew that, as the symbol of campus, the Tower’s exterior needs to be fixed so that it’s back to its former glory,” Hartzell says. If it seems like a long time until we start seeing activity—it could be more than a year—it’s because the work will require scaffolding. “Great care needs to be taken,” Stringfellow says. “We’re also talking about re-gilding the clocks. This isn’t basic work—this is highly skilled labor.”

University leaders want the building scaffolded for as short a time as possible. That means answering as many questions as possible before the scaffolding goes up, such as the salvageability of the window frames and spandrels. “The worst would be to put the scaffolding up and then get a surprise,” Stringfellow says. “We don’t want it up there for four years. We don’t want an entire class of students to go through college with that.”

The building will be covered for a minimum of two years, Stringfellow says. It is likely that during that time, scrims showing an image of the Tower will hang from the outside of the scaffolding. Many other landmarks, including the Washington Monument and Supreme Court Building (incidentally, a Cass Gilbert design), have used that technique in recent years. And yes, “we’ll still try to light the Tower,” Stringfellow says. “Even when it’s scaffolded, what can we do to make it special and acknowledge our wins? How can we make it a decent backdrop if parents are coming to campus?”

“What do students do when they graduate?” asks Bob Zlotnik. “They get their picture taken in front of the Tower.”

Stringfellow says architects and planners usually think of building materials in terms of how long a building likely will be there—50 years, 100 years. “In my mind, as long as The University of Texas exists, this building will be here, so we have to be very mindful of making good, solid decisions.”

The second sub-project is the top floor. Hartzell envisions it as a museum-like space that would serve as a hall of fame for major scholarly prizes for which the Tower is occasionally lit. Outside, Hartzell wants to “get the observation deck to be cool,” he says. “I understand why they put the cage around there, but we can do better than a cage. The Empire State Building and other landmarks have plexiglass that’s tall enough to be safe, but you can still see out of it.”

A third area of renovation will be the ground floor. The vast majority of students who enter the building only visit that floor. “When I was in school,” Hartzell says, “the Main Building is where we came to pay our bills or maybe pick up a paycheck once in a while. I think there needs to be new ways to engage students.” He sees the remodeled Texas One Stop office on the ground floor—bright, warm, and open—as a good model of what to do with other student-facing spaces on the ground floor.

Lastly, much thought is going into the grounds around the Tower, including the malls. “We really want to emphasize that this is not just the Tower, but the whole setting of our campus,” Eltife says. “We want a campus that’s inviting to students, future students, and faculty. We want an incredible environment. Look, the Forty Acres is already beautiful; it just needs some tender, loving care, and that’s what we plan to provide.” Though the Tower is the focal point of the renovation, the grounds of the core campus might be the first thing tackled.

Inspired by the creation of the Stedman Family Gardens from what was once a dirt median where motorcycles parked south of the Littlefield Fountain, Hartzell and Eltife want the South Mall to level up. The East Mall is already being redone as a place to honor UT’s pioneers such as the Precursors, the first Black undergraduates to attend and integrate the university. The West Mall, an important gateway to campus and center of student activity, will also receive an update, though details are still to be decided.

Perhaps the biggest changes outside the Tower will be to its north. “We’re going to tear down that crappy greenhouse,” Hartzell says in his no-nonsense way. (By press time, it was already gone.) In its place, possibly a café. Beautification will likely extend east of the Turtle Pond to what is now a parking lot. “Let’s take on all the controversies at once,” he says with a chuckle.

Stringfellow calls the north side “the backyard” and thinks it eventually could constitute a beautiful quadrangle, bounded by the Tower, Hogg Auditorium, the Biological Laboratory, and Painter Hall. “Make it more student-centric,” he says. “Build on the attraction of the Turtle Pond. Make it a place where people meet and hang out. Have concerts back there.”

The interior of the Tower proper, floors nine up to 27, is not in the current scope of work. “We’re not gutting the entire thing and turning every floor into beautiful office space,” Hartzell says. But that doesn’t preclude thinking about what could be in a future phase. “You could do things to reduce density and still make it cool.” This could mean renovating select floors to develop project areas and seminar rooms for students, or taking out some floors to create double-height ceilings.

But for any significant increase in occupancy, the egress problem—two ways down, not counting the elevators—would have to be tackled. Speck believes that would be relatively easily solved by adding an additional stair to the existing stairwell to form a “scissor stair.” But it’s worth noting that Cret himself warned against using the Tower in this way. While he was still designing the building, he said (best read with a French accent), “The latest suggestion of putting seminars in this tower is further complicating the situation, as it involves reliance on elevator service which has been found mediocre for educational buildings.”

The Meaning

“I find it interesting that universities have towers,” Hartzell says, citing his other alma mater, Trinity University, as well as Stanford and the University of Pittsburgh. “What is the symbolism of that?”

It’s a question Speck has thought about a lot. For decades, he has taught the meaning of architectural forms. “They organize our lives. We respond to them in a very visceral way,” he says. Throughout history, towers have been used to mark city centers, places of authority, of permanence. For a test question in his course on architectural meaning, Speck prompts his students to look at the Tower and tell him the meaning of the building. “They immediately figure out that in the whole history of architecture, a tower has been the center, the focus, the emblem that represents a community,” he says. It is unconscious for most people, but it is powerful in giving UT’s community identity. “And it’s done that beautifully for decades,” Speck says.

When former UT President Robert Berdahl left to become chancellor at UC Berkeley in 1997, Speck was chosen to speak on behalf of the deans at his farewell party. “We were roasting him, and I did a little slideshow and said, ‘What is this decision you’re making, Bob? You’re going from a campus with this tower to the Berkeley campus, which has this little weenie tower that’s a rip-off of the Torre San Marco in Venice?’”

Every person connected to UT feels the Tower’s presence in a slightly different way. Eltife says, “I remember the Tower was the focal point of our whole existence on campus. Everything revolved around the Tower and the location. I just think the Tower is such a memory for everyone who ever walked on that campus. It is what we are known for. We take pride in it, and we are going to see that it’s properly restored.”

Stringfellow sees the Tower not just as the University’s core, but as its foundation. “We are looking at a future in the next few decades where UT is poised to do all kinds of amazing new things. Our campus can advance in ways that reflect all the dynamic aspects of the 21st century, and I see this as the anchor. This is what you build off of. Having that core really represent and be where the values of UT work out of is really important.” The Tower provides that center of gravity around which everything else can orbit.

“The Paul Cret master plan has gifted us an amazing legacy,” Stringfellow says. “And even when we haven’t been as attentive to it as we should have been, it still provides a really powerful sense of place. There are not many universities that have a single building that is instantly identifiable but also becomes a stand-in for the university.”

Speck’s parents enrolled at UT in 1938, when the Cret buildings were all new. The campus was amazing, he says. The education at that time, they later told him, was not. But the aspiration to greatness was clear to them, “and after a few generations of prospective faculty members, prospective presidents, prospective students all being drawn to that vision, it became a great university. Those buildings were a really important tool in making that happen.” Moreover, there was its prominence on the Austin skyline. When Speck would visit his aunt in Hyde Park, the Tower was framed perfectly by her south-facing window. “You know, I think that’s why I’m here,” he posits with a smile. “It may well be that Tower. It’s just so aspirational: This is the bigtime! This is an important place!”

Hartzell feels the Tower and the aspiration it symbolizes still play an important role in UT’s collective psychology and its trajectory. “We believe we’re one of the nation’s top five public universities, and we aspire to be the highest-impact university among them. It still feels like the Tower is part of that. And other than the Hook ’em Horns sign, I can’t think of any more lasting symbol.”

He has felt its effect as president. “There are days when the weight of this space, the weight of the building, raises my sights and ambitions. I’d like to think I’d do my best in whatever office I was given, but I come in here and I think, This is a serious place. I better bring my best today because here I am in this incredible space in the heart of campus, looking at the Capitol, looking at the malls, looking at the students going by.”

But he also remembers the feeling it evoked when he was a student. “I remember walking up those steps to do something in this building and thinking the sky just looked a little bluer behind the Tower.”

Photos courtesy of the Texas Exes Archives and Marsha Miller