The Blanton Museum of Art Debuts Its Stunning New Entrance and Grounds to Austin—and the World

When it first opened on campus in 2006, the Blanton Museum of Art was tucked away like a secret. It had one entrance, which directly faced its companion building that held offices and classrooms. Long sidewalks shaded by trees secluded it from the rest of campus, and a path led visitors out onto Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, back into the bustle of Austin. It was quiet and contemplative—but it didn’t come anywhere close to screaming, “world-class art museum.”

But big changes have come to the Blanton grounds, which are now immediately visible when driving down Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. Calla lily-like structures seem to have sprouted overnight around Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin, and lush patio space flanked by a bright green mural unfolds from the Brazos Garage, greeting visitors, students, and staff with a neon yellow, “HI.”

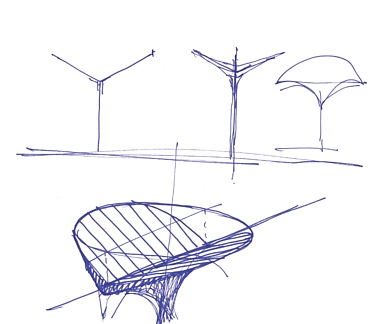

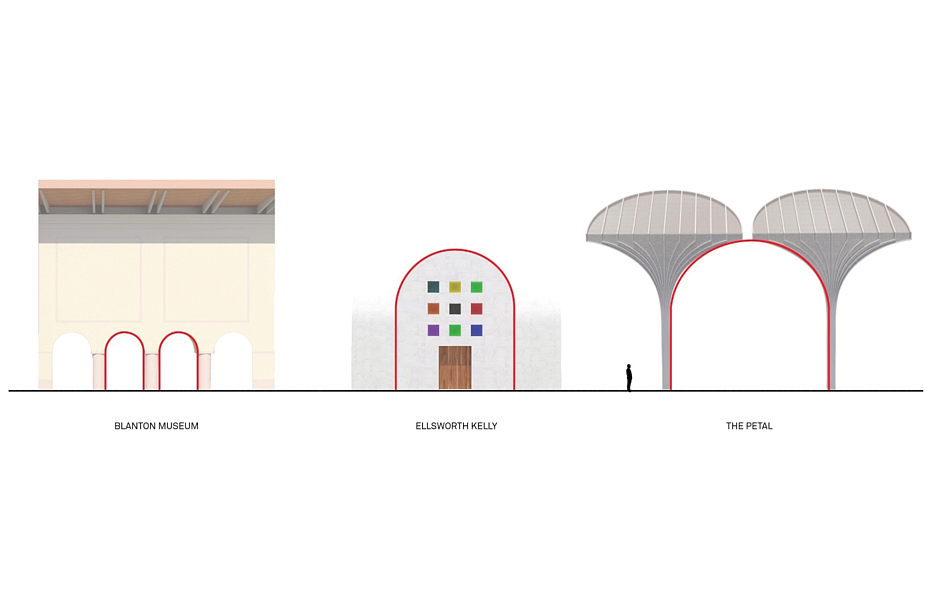

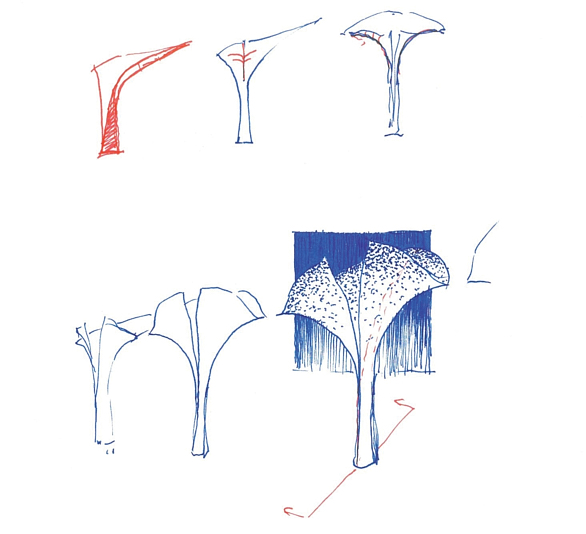

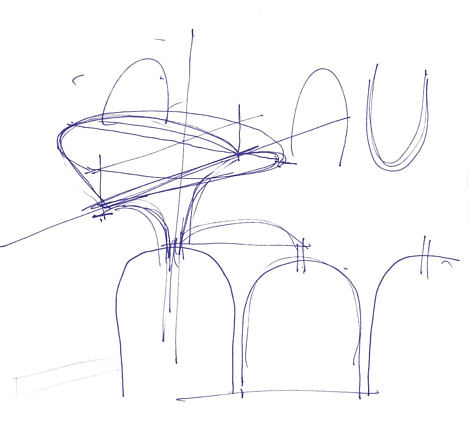

A project that came out of “solving problems but also looking at the future,” as Director Simone Wicha put it, the grounds update includes new, clearer entries to the ticket desk and galleries, four art installations, pathways, patio space, two stages for events, new and updated signage, and those shade-giving “petals” drawing eyes from the road. The $35 million project, designed by architecture firm Snøhetta and supported by the Moody Foundation, Sarah and Ernest Butler, the Still Water Foundation, the Kahng Foundation, Sally and Tom Dunning, and other donors, broke ground in March 2021 in a virtual ceremony.

But Wicha has been working toward this reimagining for more than a decade. When she became director of the museum in 2011, she knew she wanted to focus on making the Blanton more visible and accessible. One of the biggest issues she noticed: The Blanton had no clear entry point. The museum looked similar to other buildings on campus, and repeating archways that created the building’s covered porch also created a confusing path to the front door. It also faced the unique challenge of having three backs—one facing Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, one facing Brazos Garage, and one facing Speedway Mall on campus.

“Over the past eight years or so, I started hearing about how extraordinarily we hung our collection ... and that our exhibitions and our education program was so strong, but people would say, ‘It’s the best-kept secret,’” says Wicha, BS ’96. That people were having trouble getting to the Blanton and finding their way to its doors was frustrating. There wasn’t a good reason the Blanton was a secret.

Instead of just adding more signage, Wicha, the Blanton curators, and the Snøhetta architects picked something else to declare the museum’s location: more art.

‘‘Most of us think of art as being locked in a building protected by guards, or pieces of glass in front of it, or ropes going around it,” says Snøhetta founding partner Craig Dykers, BArch ’85, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus. “Whereas actually art is very much alive. It should be understood as a living thing. It’s a part of society that changes over time. It grows old. You get younger works of art. And in that way, we need to take it out of the building and also make it a part of the place and not simply part of a gallery.”

To create the new “key gateways” to the Blanton, artist Kay Rosen and sound artist Bill Fontana were enlisted for site-specific installations. Rosen’s piece titled “HI,” a blue mural with the letters “ABCDEFGHI” in sequence, with the “H” and “I” in neon yellow instead of white, faces the Brazos Garage and the new drop-off zone, where 12,000 schoolchildren will disembark buses every year to visit the museum. On the north side of the building is now the Butler Sound Gallery, where Fontana’s work of looping audio from sites across Texas—bats from under the Congress Avenue Bridge, babbling water in Barton Springs—plays through 20 speakers during museum hours. But the southern gateway that leads into the Moody Patio between the gallery building and check-in building may be the most striking, thanks to the “petals” designed by architects at Snøhetta.

“We believe that once these grounds are opened and accessible to everyone, people are going to go more often to the museum,” Dykers says. “And people … who didn’t know what was there will be profoundly inspired for the rest of their lives.”

On top of bringing in new visitors, Wicha sees the updates as offering everyone, familiar with the Blanton or not, a place to sit and stay a while in a way they didn’t before. “It’s really important for us to be in a national conversation in the art world. But we also wanted to relate to people’s lives,” Wicha says. “Art is so fascinating, and it brings joy and it can bring calm and it can bring you to so many new ideas or different ways of thinking. Let’s celebrate that, but let’s also make [the museum] a place where people want to hang out and linger and do that.”

As visitors move into the new patio, one of the first things they might notice is all the color. A bright yellow archway now creates a clear entry for the ticket desk, while across the patio a flipped archway in the same shade forms a windowed lookout from the gallery. A work of many-colored threads from Gabriel Dawe, “Plexus No. 44,” produces an ever-changing rainbow overhead in the atrium housing the ticket desk. The main wall of the Michener Gallery Building is now outfitted with the vibrant green mural from the late Cuban abstract artist Carmen Herreras, “Verde que te quiero verde (Green How I Desire You Green),” which flanks the front entrance. And standing on the new patio, looking toward campus sits Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin, another project Wicha was instrumental in bringing to campus.

All these new gateways and works outside are meant to distinguish the Blanton, which was initially designed to complement the existing architecture on campus, but consequently made the museum difficult to notice or find—something you don’t particularly want for an art museum.

“[The Blanton] did very much blend into campus,” Wicha says. “That doesn’t feel that welcoming to them—it doesn’t even feel that obvious to them that that is the art museum … It was designed like a campus building, where a student knows where they’re trying to get to and will navigate to their classroom. But that’s a very different way of approaching a place than a visitor does to an art museum.”

Coinciding with the reveal of the new grounds, the Blanton is also expanding its hours, offering free admission for all on Tuesdays (instead of Thursdays), and implementing Second Saturdays, a series of community events on the second Saturday of each month with music, food, and more.

Wicha first met Dykers when he was speaking on campus in 2016. She was in the process of meeting with several architects and wanted to pick his brain about the project. Instead, Dykers and his wife, Elaine Molinar, BArch ’88, and the rest of the team at Snøhetta ended up being the perfect people for the job—partially because Dykers and Molinar remember the days when the Blanton wasn’t a museum, but still managed to inspire them as students.

Before the Blanton was the Blanton, it was a collection of artwork that hung in different areas of campus like the Harry Ransom Center and the Tower. But plans for a building to give the art a proper home dated back to 1979, and an official building campaign began in 1993 under museum director Jessie Otto Hite, BS ’69, MA ’82. In 2006, the Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art opened after years of fits and starts, named after oilman Jack Blanton, BA ’47, LLB ’50, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, who had discovered a love of art on a Flying Longhorns trip to Europe and donated millions to the project.

“When I went to school at Austin, there was no Blanton,” Dykers says. “[Some of the collection] was at the Humanities Research Center. It was right near the architecture school, and I went there at least once a week. It was so powerful to me … This was over 40 years ago that I saw those paintings, and I could tell you exactly what they look like today.”

“It was a great place to go for a break and to break from studies, but also a source of inspiration,” Molinar says. “The works of art there are just phenomenal. And I think the role that art plays in education, no matter what you’re studying, is really critical. To be able to experience the vision of an artist and to kind of understand their worldview, which may be different from one’s own, is very important in my education.”

But Wicha didn’t have that experience. That’s part of why it was so important to Wicha to have this reimagined Blanton where its works were open to everyone.

“I went to [the collection] … maybe once or twice. It was not part of my life when I was a student on that campus,” Wicha says. “For me, that was a really missed opportunity. And so, I wanted more than what I was able to get when I was a student.”

Besides being The University of Texas art museum, the Blanton also serves the role of being the main art museum for Austin—the city doesn’t have the collection of a MoMA or a LACMA or Smithsonian, and despite its reputation as a creative city that keeps it weird, Austin doesn’t always emphasize the visual arts, Wicha says.

“That’s something that I would be frustrated about,” Wicha says. “And I thought, well, what I am frustrated about, either I build it or don’t build it. You know, these things don’t just appear. We need a strong ecosystem and have a strong ecosystem of the visual arts. We need a strong museum or strong museums, we need galleries, we need all of that. And an art museum, in my opinion, plays a really important role in being a great city—you have good schools, you have good parks, you have good medical centers, and you’ve got good art museums.”

The Blanton has everything required of a good art museum. It holds the largest public collection in Central Texas, one of the oldest collections of Latin American art in the U.S., and a space for major traveling exhibitions. And with these updates, Wicha sees this as a new era of the Blanton, where it’s no longer the best-kept secret of Austin, but is known and loved—and unmissable.

“At the end of the day I’m incredibly proud because we’ve taken some steps—and there’s so many more steps, but it’ll just keep building and growing from here, as long as our community continues to care for it and nurture it,” Wicha says. “That’s probably the most exciting part: imagining what the future can look like.”

CREDITS: Casey Dunn, Snøhetta