Good Reads Q&A: A New Memoir from a Longhorn Astrophysicist Looks Up

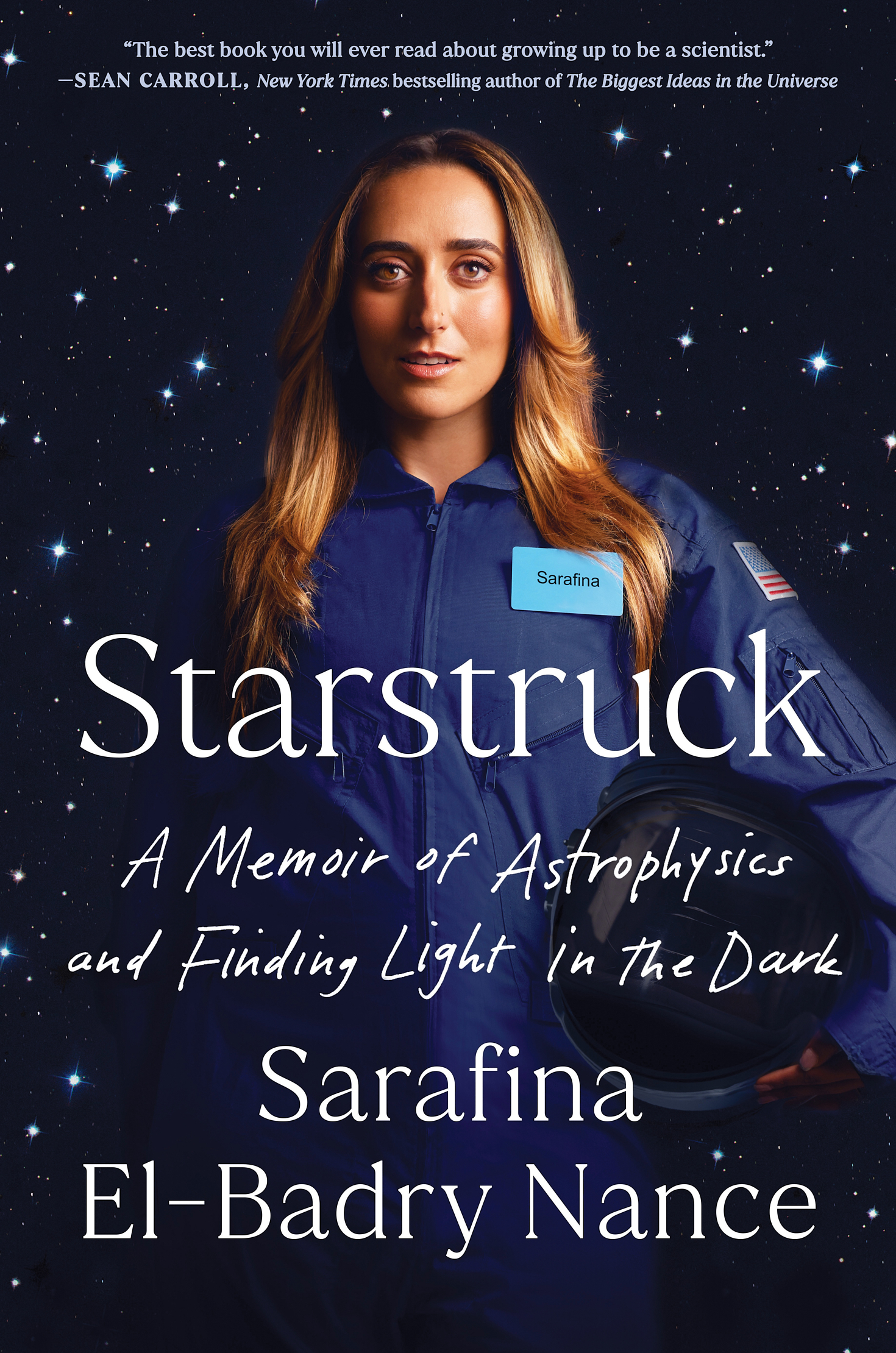

Sarafina El-Badry Nance has always loved looking up at the stars. It’s one of the first things she talks about in Starstruck, her memoir released June 6 from Penguin Random House. She explains that when we look up at the stars, what we see in the night sky is only a small fraction of the world around us. That’s what Nance, BS, BS ’16, wants readers of her book to understand about her, too—that she’s more than the sum of her parts. That she’s an astrophysicist studying for her PhD at the University of California–Berkeley, that she’s a science communicator, that she’s an Egyptian American woman, and that she cares deeply about women’s health (she had a double mastectomy in her 20s after discovering she carried the BRCA2 gene, a predictor of breast cancer).

Nance’s belief is that we humans, like space, contain multitudes. And Starstruck speaks to those themes as she takes us through her journey, from being a young Austinite gazing up at the night sky who wasn’t naturally good at math and science to joining NASA’s Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, a research station for astronaut missions to the moon and Mars.

The Alcalde sat down with Nance to discuss the book.

First of all, what does it feel like to write a memoir as a 30-year-old?

I got to this point right after I had my double mastectomy a couple years ago, where I felt like there were a lot of overlapping themes in my medical journey and my scientific journey, and it felt like that story hadn’t been told in the way that I could tell it. It really felt appropriate. And this is going to sound really cliché, but [it was] this journey towards self-actualization and trying to figure out what this is all about and why we’re doing it at all. And I think that story doesn’t have to be told when you’re 50 and you’ve already reached the apex of your career. I think there’s something really relatable in having a millennial talk about what it has been like to find their place in a field like this. People say representation matters, and I believe that to my core. I think that stories like mine and voices like mine haven’t really been elevated before now, and we’re still trying to make that happen.

Why did you want to write the book?

I was tired of being the only woman in my science classes. In my life as an underrepresented minority, I’ve encountered my fair share of gatekeepers. I wanted to really examine what it means to pursue one’s dreams anyway. Ultimately, I think I had to learn to become my own best advocate, but I wanted to be really honest about my journey and share the heartbreak and the joy because really it’s taken both to get here. My goal is that others know that they’re not alone, even though I think I felt alone a lot of the time in my own journey.

The most poignant section of your book is when you found out about the 2011 protests in Egypt; you were also on your way to meet the professor who would later become your mentor at UT, Dr. J. Craig Wheeler. Can you talk more about that moment?

I try to really showcase the human in the science. This is a book that shares my personal journey becoming a scientist, but ... it’s also these turbulent personal struggles that have impacted who I am as a human being, which inevitably impact the way I think about the world and how I respond to scientific inquiries. And [in this section of the book], you have these two incredibly important moments that really shape one’s life happening in tandem. How can you honor both of them and reconcile that you’re not two people? You have to be both, and I think that we often think of scientists as sort of devoid of any other sort of humanistic characteristics. And I think it’s really important to share that that’s unrealistic. I think that the sequence of talking to Dr. Wheeler was really important because I recognized not just my feelings of non-belonging, but this kinship with my mom in this Egyptian heritage that I had been reticent to fully explore or understand, and it didn’t even feel like a choice in that moment. It felt like my heart was speaking. And Dr. Wheeler equipped me with the tools to do then and later on, to basically say, “It’s OK to have both.”

I found a viral Twitter thread where you talked about getting a zero on your quantum physics exam, and about failure. Can you talk more about that?

I didn’t grow up being good at physics and math or science in general. I thought it was really hard. I was way more of an English person. I think in spite of that, I loved the stars and I felt this sort of existential pull to look up at the night sky and continue to try to explore it. And what that meant is that I failed a lot because I wasn’t inherently good at these tools that you need in order to do astrophysics. It took a lot of hard work. It took a lot of incredible mentorship and community with other people in the programs, but it also took a lot of failure. And I think there’s something really important about normalizing failure because ultimately, science is about failure. You fail and fail and fail until you don’t, and you get a result, and you publish about it. Or if you fail, that can be interesting, too.

What would you say to a young girl who might identify with your story?

I had this passion for the night sky. I love feeling small, and I feel like the perspective that the night sky brings allows me to feel connected, not just to the universe, but to people around me. And I think that sense of smallness can also bring a sense of belonging. We all belong here, because we’re all part of this big universe. And I think, for anybody who feels like they might not belong, my hope is that my story shows them that they do.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

CREDITS: Courtesy of Serafina El-Badry Nance