Introducing the 2023 Texas 10

There are myriad things that make a student’s time at UT so memorable. But for nearly every Longhorn, there’s often one thing at the center of it all: an educator who inspired, supported, and shaped their future far beyond the Forty Acres. Each year, the Alcalde gives you the chance to nominate those very professors. We’re thrilled to introduce this year’s Texas 10.

Photographs by Jeff Wilson

Tamara Bell

Assistant Professor of Instruction, School of Advertising & Public Relations and the School of Journalism and Media, Moody College of Communication

Years at UT: 7

Although Tamara Bell, MA ’93, PhD ’04, often tells students she’s had “a complete hodgepodge career,” she is grateful for the winding road that led her to teaching and now cannot imagine doing anything else.

Growing up with a knack for writing and an admiration of Watergate-style investigative reporting, Bell majored in journalism, hoping to be a real-life hero like Clark Kent or Lois Lane. But after she got her first job as a reporter and began interviewing government officials, she realized she wanted to be on the opposite side of the table—writing legislation and enacting change. So she moved to Austin, where she worked in the state Legislature as a chief of staff and press secretary for two House members and as a senior policy analyst for a Senate committee.

While in Austin, Bell decided to pursue her master’s, then later, her PhD in journalism from UT. This introduction to academia blossomed into an opportunity to teach journalism and public relations, which now allows Bell to change the lives of individual students.

“Every job I’ve ever had, I’ve gotten because I can write. So I tell [PR] students you have to be able to tell a story … we are the storytellers of businesses, of brands, of nonprofits,” Bell says. “But writing is more than just the mechanics. It’s the intangibles of the tone, the words you choose, your voice. All the things that make you unique.”

Bell currently teaches a mix of introductory and upper-division courses, which means she sees students at the beginning of their education and on their way out the door. It also means she gets to witness their growth as storytellers—something she takes pride in shaping.

“My job is to make sure they get their dream jobs,” Bell says. “When I hear from former students … and they tell me they’re doing something amazing, those days make me want to do cartwheels down Guadalupe.” —Ava Motes

Daniela Bini

Professor of Italian Studies and Comparative Literature, College of Liberal Arts

Years at UT: 50

Daniela Bini, PhD ’78, has been at UT for 50 years, and she’d stay another 50 if she could. She’s the heart and soul of the Department of French and Italian, and she’s retiring this year.

“This coming at the end is a very fulfilling reward,” Bini says. “I’m very emotional about it. I’ve got students who say, ‘No, you shouldn’t retire,’ but I’m 78 years old.” Bini has three children, and wants to spend retirement with them, her husband, and grandchildren. And she certainly deserves it after half a century spent giving everything she had to her students.

“I’m an extrovert and a people person,” she says. “I think we need others in order to grow and in order to improve and to define yourself. I wanted to be an educator because I want to be educated. I believe that it’s a reciprocal process.”

She, like other professors honored this year, says she learns from her students every day.

“I get out of every class changed. Sometimes when students want to ask a question, they say, ‘This is a stupid question,’ and I always tell them there is no stupid question. Because every question that you ask will trigger my mind and their classmates’ minds.”

Bini says this is especially true when teaching students about another culture. She was born in Rome and primarily teaches classes about Italian literature, but her most popular class is “Sicily: Myth, Reality, and the Mafia.”

“I want my students to have an open mind to diversity, to difference, and to be able to question established truth and to question ourselves,” Bini says. “If I have students who come out with an open mind, they are ready to accept differences and measure themselves against others, because as they improve—we will improve.” —Katey Psencik Outka

Isil Dillig

Professor of Computer Science, College of Natural Sciences

Years at UT: 9

Computer science professor Isil Dillig’s favorite thing about teaching is being a mentor.

“Basically, my job is raising a new generation of researchers and getting them to think through what makes for an interesting research problem,” Dillig says.

Computer science isn’t all about programming, Dillig says. It’s about thinking.

“I hope my students walk away with the ability to think independently and develop problem-solving skills. It’s not just memorizing stuff, but really the ability to think through things and approach problems in new and innovative ways. I think that’s really important,” she says.

That’s a big part of what she teaches in her discrete mathematics course for honors computer science students. The class has a reputation for being hard, she says, but the students enjoy it anyway because she makes it as interactive as possible. Instead of just lecturing or solving math problems herself, she calls for volunteers to work through problems on their own in front of the class.

“As they’re putting the solution on the board, I’ll explain what’s going on. Or if there’s an issue, I’ll get the class to engage: ‘What do you guys think? What’s going on here? What are your comments?’ And I try to make it interactive and engaging so they’re not passively learning,” Dillig says.

Most professors at UT are dedicated to helping their students find jobs after graduation. Dillig has taken that to the next level—she’s hiring them.

In addition to her teaching and research, she recently cofounded Verdise Inc., a company that provides security solutions for blockchain services.

“The idea behind this research area is to develop techniques to automatically improve program correctness and automatically find bugs and security vulnerabilities and programs,” Dillig says. “I recently got interested in blockchain. So, I was approached by investors who saw my research. One of my former students and one of my current students who were working on this [with me], we decided to join forces.” —K.O.

Kishore Gawande

Chair for Business Government and Society Department, Fred H. Moore Centennial Professor of International Management, McCombs School of Business

Years at UT: 9

Economics professor Kishore Gawande throws out 25 percent of his syllabus every semester.

It’s not because “Business and Global Political Economy” isn’t a good class—Gawande’s one of the Texas 10 for a reason—it’s because the world is always changing, and Gawande wants his syllabus to reflect that.

“Economics is not difficult,” Gawande says. “We live it every day. When you go and you purchase something, you’re an economist. You don’t draw graphs in your head and relate them to analytics and data, but you’re doing all that.”

That class is Gawande’s favorite to teach because he lets the students lead.

“I speak very little, actually. I speak 15 minutes maximum every class, and the rest is student participation. Every class there’s a case assigned, and people come in ready for discussion,” Gawande says.

It’s what one of Gawande’s former students liked the most about the class, according to what they wrote when they nominated him. And Gawande likes that class so much because he sees it change every semester.

“Every class is different, and it’s shaped by their upbringing, what their priorities are, where they think the world is headed,” Gawande says.

That’s part of the reason he wanted to be a professor.

“As an economist, you can go in many different directions, but there was no other option for me. I wanted to be an academic,” Gawande says. “I’m very well-trained, and I wanted to apply it to do research and teach, and it’s a dream job. I’ve consulted here and there, but the reason they like my consultation is because of my research and being an academic, so I get the best of both worlds.” —K.O.

Theresa Martines

Assistant Professor of Instruction, Department of Mathematics, College of Natural Sciences

Years at UT: 4

Within 30 seconds of a conversation with her, it becomes clear why mathematics professor Theresa Martines’ former students nominated her for this award.

She exudes kindness and warmth, and she really loves math. And she wants her students to love it, too. Or at least … hate it a little less.

“Every kid has one class in college where they didn’t even have to attend. They barely tried. It was so darn easy. And they’re not the same for everybody, but it’s almost never math,” Martines says.

Martines mostly teaches STEM majors, but that doesn’t mean they’re super into math, either. Martines recognizes her discipline has a reputation for being challenging, but she loves seeing students who walk in on the first day dreading class and walk out on the last day with a changed perspective.

“When they make that transition, that’s the stuff that’s good for the soul,” Martines says. “Out of 120 kids, if there are two kids in the room who do that, that’s all I need. That’s my fuel. It’s the coolest feeling.”

When asked about her teaching philosophy, she says it’s all about comfort.

“I crack the same silly jokes every first day of class. And then they talk in class, and they interact with me and each other, and that’s all I want,” she says.

She’s so dedicated to her students that she commutes from San Antonio and leaves her house at 4 a.m. to get to campus. And “dedicated” is one of the words her nominator used to describe her—along with encouraging, caring, kind, funny, passionate, and engaging.

When asked how she felt about that description, she says:

“I love it, because I feel like that’s what I’m trying to do. And I’m like, ‘Oh, good, it’s coming off that way.’ Once I start to get to know [my students], I tell them I put on a show. I have lecture notes and I go over them constantly and I think, ‘What joke do I want to tell this time? What story feels good here? Are they freshmen, and should I be very motherly, or are they juniors and seniors and I should be a little more chill?’ It’s that little stuff that has nothing to do with math, but it gets them excited. It makes me happy.” —K.O.

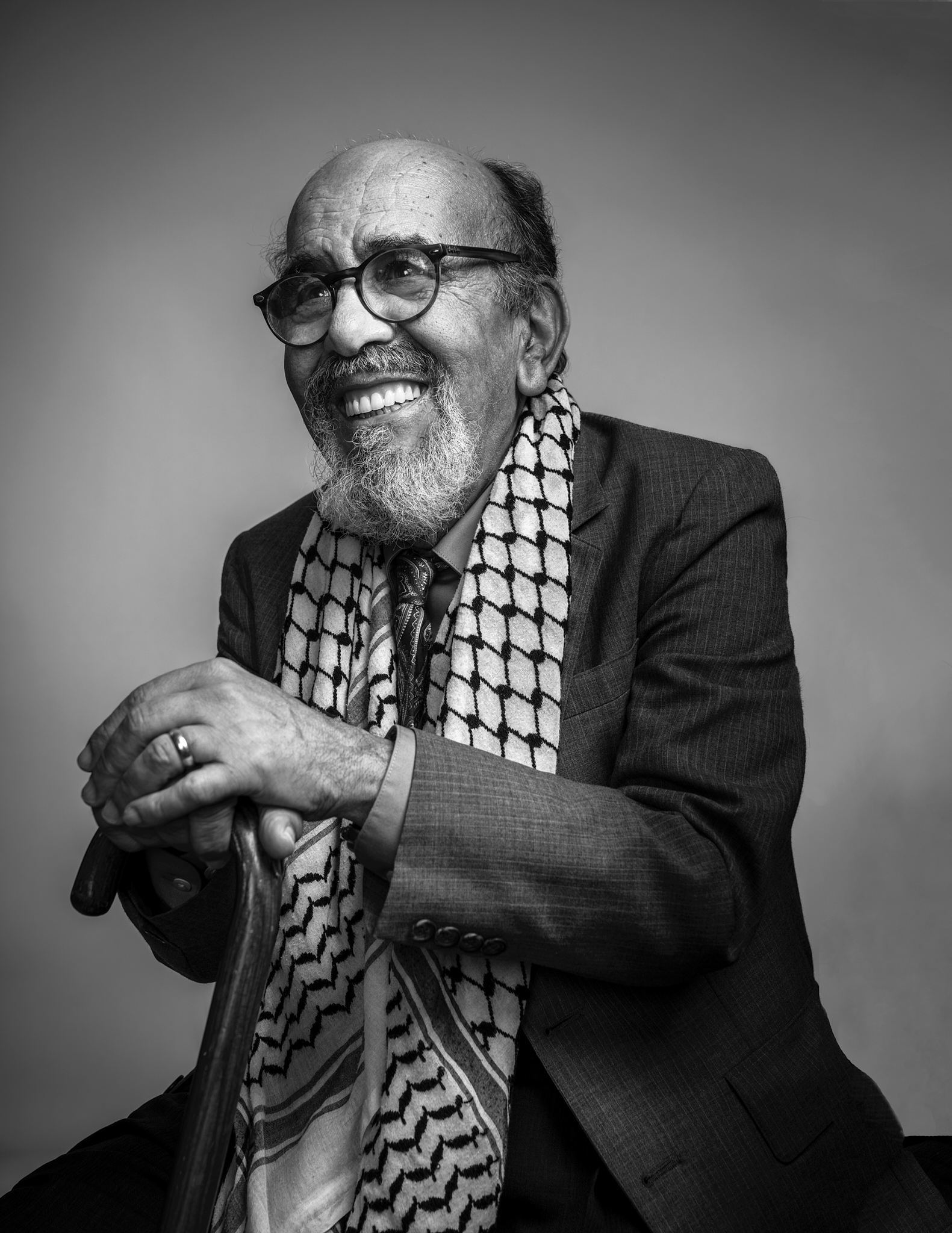

Mohammad Mohammad

Associate Professor of Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies, College of Liberal Arts

Years at UT: 23

Mohammad Mohammad begins every introductory Arabic class by asking students to write down the traits they associate with Arabs, and responses range from stigma about terrorism to positive recollections of Arab hospitality. But no matter what preconceptions students have, Mohammad hopes to provide a deeper understanding of his culture.

“The best way for you to know me is through my language, and in order for you to learn my language, you have to learn my culture,” Mohammad says. “If you love us as Arabs, I want you to know why, and if you hate us as Arabs … I want you to get to know us first.”

As a child, Mohammad was fascinated with building bridges across the rain-flooded streets of his home in Jordan. Although he did not have the opportunity to study civil engineering or architecture at the University of Damascus—where he graduated two years early with a degree in English—his career as an educator is dedicated to building metaphorical bridges between Arab and American cultures.

Mohammad, or “Momo,” as his students call him, always keeps a book in tow and has a lifelong thirst for knowledge, which he seeks to instill in others. Having always been “in love with Arabic language,” Mohammad eventually went on to complete a PhD in linguistics and syntax at the University of Southern California. On his first day as a teacher, his father told him something he still holds to this day: “Knowledge is a blessing, but that blessing has a condition. You have to transmit that knowledge to whoever asks for it.”

“I think of myself as a steward,” Mohammad says. “There’s a great deal of knowledge in my head and I have to pass it on.” —A.M.

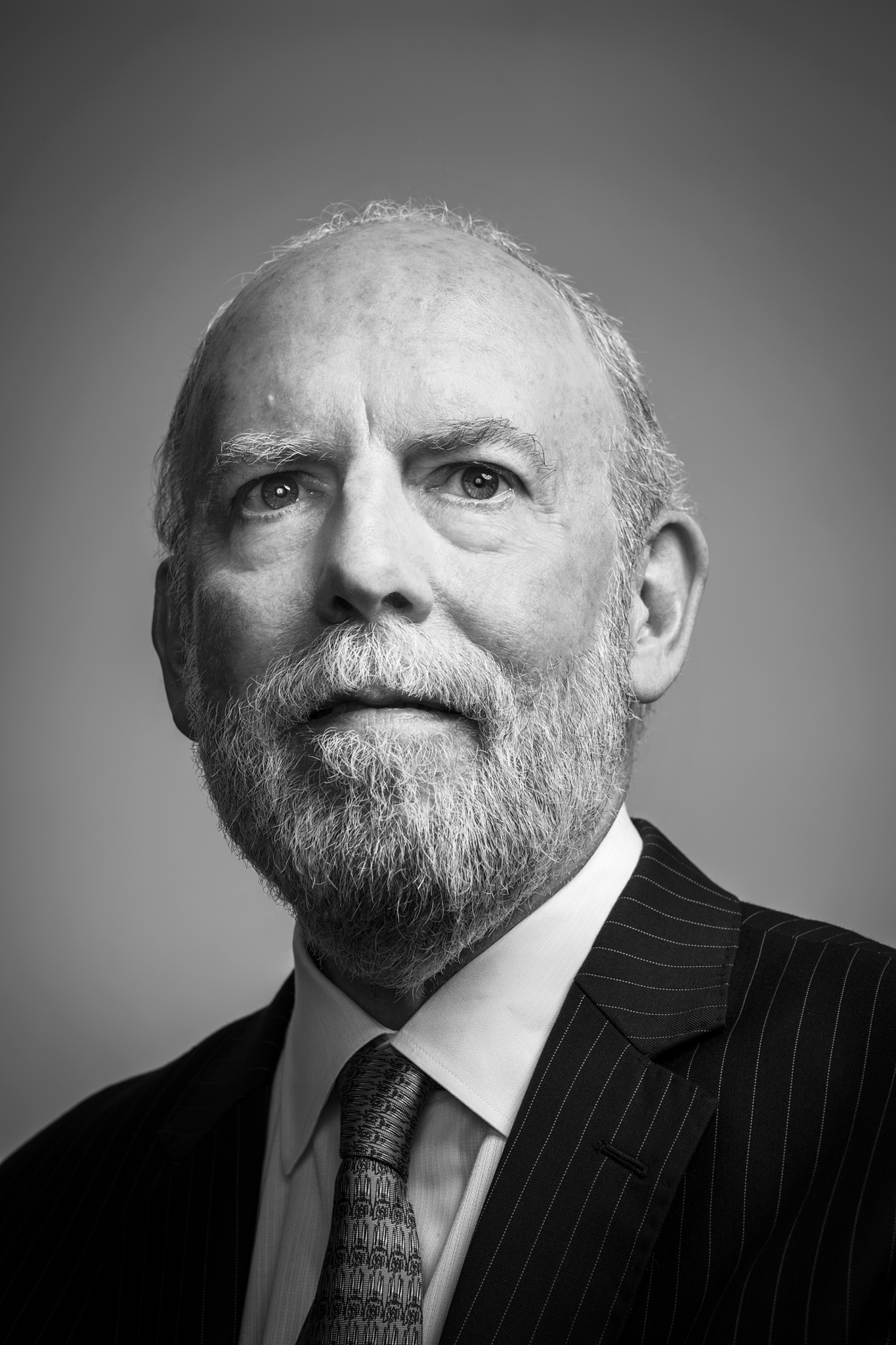

Stephen Reese

Jesse H. Jones Professor of Journalism, Moody College of Communication

Years at UT: 41

Although Stephen Reese has traveled and lectured all over the world, he still says there is no better place to be than a college campus. The son of a University of Tennessee business professor, Reese spent his youth in a collegiate climate. Now, the self-proclaimed “lifelong learner” cannot imagine being anywhere else.

Reese has worked on the Forty Acres since 1982, teaching everything from introductory journalism classes to the signature course “Understanding 9/11” and the Plan II elective “The Politics of Conspiracy Theories.” As the Jesse H. Jones Professor of Journalism, Reese has previously been the director of the School of Journalism and the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs in the Moody College of Communication. In true journalistic spirit, he is known for asking thought-provoking questions to engage students.

“I like to have discussions in class … to pose something for students to think about,” Reese says. “I try to be a catalyst and model that I’m a person who is also thinking about these things.”

A humble intellectual, Reese speaks with intention and still gets excited when he publishes research about press performance and the globalization of journalism. And while he’s been teaching for years, he admittedly gets nervous at times. Reese has the unique challenge of teaching an 8 a.m. class—a tough time slot for students and professors trying to keep their attention—but he finds relief in getting lectures out of the way early in the day.

“That works for me because I get so wrapped up in thinking about the class, it’s better for me to go ahead and do it early on so I don’t just pace around think about it all morning,” Reese says. “It’s funny how that works. You would think after all these years, I’d be squared away.” —A.M.

Marissa Rylander

Associate Professor, Werner W. Dornberger Centennial Teaching Fellowship in Engineering, Cockrell School of Engineering

Years at UT: 9

Imagine Elle Woods from Legally Blonde, but as a mechanical engineer instead of a lawyer. That’s Marissa Rylander, BS ’00, MS ’02, PhD ’05.

“When I first started at UT, I came in with my pink briefcase. My husband, who is also a mechanical engineering professor at UT, laughed at me. He was like, ‘Yeah, I saw you on the elevator.’”

“I’m not super fashion-oriented or anything,” Rylander says, “but I wanted to show it can be fun.”

When Rylander was a student at UT in 1996, she says she was often the only woman in the room in her department.

“I looked at it as a challenge,” Rylander says. “No one in my family was an engineer, so I had no one to identify with. I thought about that, and I thought how important a support system was. I think about academics as an intellectual adventure, but also an opportunity to provide that heart. We’re here for each other. If at the end of the day we’re not kind and caring, none of it’s worth it.”

Her commitment to supporting women also shows through in her research. She’s working on a team developing better ways to warm breast milk and chip technologies to screen new therapies for breast cancer. After she had a child, she noticed the technology was lacking and wanted to alleviate frustration for parents and provide a safer alternative for babies.

“I was like, ‘Why are so many technologies for mothers and babies so backward? Women aren’t involved in developing them, right?’” Rylander says. “I’ve been trying to branch out into some of those things because I feel like it’s time to give back to women and motivate our own students.”

And it’s working. One of Rylander’s nominators wrote, “She was the first female technical professor I had and showed all the women in class what it means to do it all: to be a mother, a scientist, a wife, a researcher, an amazing engineer.”

When asked how she felt about that, Rylander teared up.

“Especially when you’re a mother … you’re balancing so many things. You always have this guilt. And it just grows because you want to help everyone. You want to give your best. So that means a lot.” —K.O.

Michael Starbird

University Distinguished Teaching Professor of Mathematics, College of Natural Sciences

Years at UT: 49

Mathematics professor Michael Starbird wants you to know that there’s no such thing as a math brain. Anyone—including writers, poets, and politicians who might notoriously avoid math at all costs—can understand it and apply it to their lives.

“Doing mathematics is the same as any other kind of thinking,” he says. “I don’t want to have my classes be a math world, and then when students leave that world, there’s nothing left.”

Starbird is the kind of math professor the most math-averse people should have. He’s quick to be reassuring, kind, and patient—kind of like if Mister Rogers was a mathematician.

“When a student is participating in my classes, they’re developing the skills that allow them to become better writers and better poets and better politicians and better business people and better citizens of the world,” Starbird says.

Starbird says there’s reason to feel hopeful about the future of the world; just look at the data (or, the math). Crime rates are going down, as are child mortality and maternal mortality rates. He tries to bring that hopefulness to the classroom, too. He wants to teach his students to be flexible, curious, and open-minded, no matter what they do after graduation.

“If students adopt a constructive and effective style of thinking and acting, that’s a great step in having the world changed,” he says. “And I don’t count success as a person who goes off and becomes a big shot. I’m talking about a person who has a family, and who helps their neighbors, and is just a constructive member of everyday life. To me, that’s the goal.” —K.O.

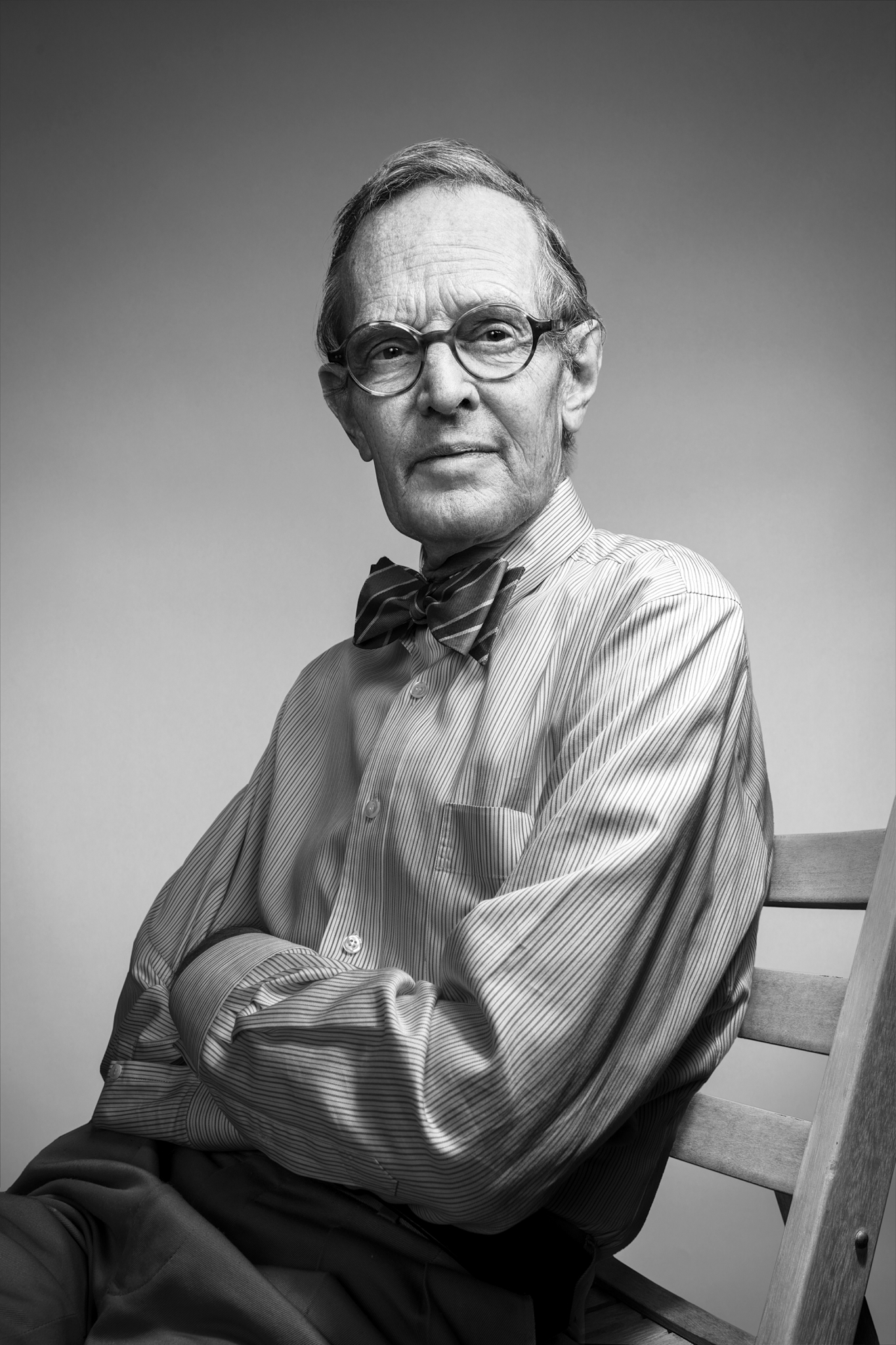

Paul Woodruff

Professor Emeritus, Department of Philosophy, College of Liberal Arts

Years at UT: 50

Paul Woodruff is quick to offer tea and a warm jacket to the students who drop by his home for a visit on chilly afternoons. Although he is now retired from teaching courses, Woodruff still serves as a Plan II thesis advisor.

Of the many profound impacts Woodruff has made on UT, perhaps the most tangible comes in the form of an elliptical table. Woodruff designed and handcrafted

the famed seminar table in the Joynes Reading Room located in Carothers Dormitory, which comfortably seats 20 students such that any two can make eye contact. This

provided an ideal environment for Woodruff’s discussion-based classes, which were

just as much a lesson in how to relate to others as they were in literature or philosophy.

“When people ask me what my teaching philosophy is, I tend to say, ‘I’m against teaching. I prefer learning,’” Woodruff says. “I’m a socratic, so I try to ask interesting questions ... and get people involved in discussions.”

As a philosopher, writer, translator, and educator at UT since 1973, Woodruff brought this spirit to all his roles. He was department chair for 24 years, then director of the Plan II Honors Program and dean of Undergraduate Studies—where he pioneered faculty-led signature courses to give all freshmen the opportunity for one-on-one engagement with professors and to learn something outside of their chosen majors.

Woodruff received his PhD in philosophy from Princeton and has dedicated his academic studies to ethics and leadership dating back to Ancient Greek society. After serving as an officer in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, Woodruff saw firsthand how combat challenges conventional morality. His most recent publication, Living Toward Virtue: Practical Ethics in the Spirit of Socrates, makes sense of such applied ethical dilemmas, which sometimes even arise in professorship.

“One of the most important things a professor is teaching is how to treat people when you have authority,” Woodruff says. “[Students] remember how you treat them and how you encourage them to think … [so I] wanted to provoke them to think and say and write things that would be worth their while to remember.” —A.M.