The Famed Scottish Rite Dormitory Is Celebrating 100 Years This Fall

For the past century, the Scottish Rite Dormitory, a stately, Georgian-inspired residential building, has sat on a picturesque plot of West 27th Street. Three hundred and fifteen female students call it home each semester. It’s tended by a staff of residential advisors, maintenance people, and housekeepers, many of whom have been employed there for decades. SRD, as it’s affectionately known, is older than the Tower, Gregory Gym, and the Union, and has earned a spot among The University of Texas’ most iconic buildings—even if it is technically off-campus.

The dorm has housed a hundred years’ worth of memories for women attending UT Austin, and in the process, has served as a microcosm for how their roles within the university and society have changed. Some of the strict rules established when it opened in 1922, like needing a chaperone’s approval for a date, or no laughing or singing past 8 p.m., are long gone. While others, such as limited visiting hours for men, still exist in some capacity. In October 2022, Scottish Rite Dormitory will host its centennial celebration and is expecting thousands of former residents and their families to convene on the well-manicured grounds for a weekend of festivities. Before the CCBs are passed out (more on those later) the Alcalde is taking a look at this dorm’s storied past and how it’s adapting to the 21st century.

SRD residents—usually referred to as “the girls” or “sardines”—are part of a unique sisterhood. They celebrate traditions that began during Warren G. Harding’s presidency and sleep in rooms that have housed generations of women before them. For some alumnae, the experience ignites a fervent devotion that has inspired no fewer than three books, among other things.

“We have an alumni group! How many dorms have an alumni group?” SRD director Mary Mazurek muses as she walks through the dorm’s grand first floor, pointing out recent renovations and improvements. Some of the upgrades, such as fresh landscaping and improved walkways, have been made especially for the reunion weekend, while others, such as painting the hallways, were done because no one on staff could remember if they had ever been done.

Those who return will still find it recognizable, which is kind of the point. When it opened, SRD was designed as a transitional space between a woman’s childhood home and the adult world. It was originally built exclusively for the relatives of Master Masons, a term used to describe members of the Texas Mason Lodge in good standing, though that rule has also loosened as time has marched on. Still, stepping inside the building harkens back to a bygone era, a time of curfews and panty raids, candlelit dinners and formal dances, just now outfitted with Wi-Fi and a mail area filled with Amazon packages. Its vintage look has even captured the eye of Hollywood producers who have turned it into a film set for big-name movies like The Newton Boys and Temple Grandin.

“This place has survived for 100 years,” says Amie Stone King, BFA ’97, MA ’00, Life Member, a former resident who lived in SRD in the 1990s and is the author of It’s a Sardine’s Life for Me: A Memoir of the Scottish Rite Dormitory. “It has seen so many world changes, and they have actually been able to adjust to them and keep themselves modern.”

SRD was first conceived in 1920 in response to a familiar problem: Austin had a housing shortage. The University of Texas had too many students and too few places to put them. In the late 1800s, it fell out of fashion for universities to offer dormitories, so, by 1920, UT could house only 340 of its more than 1,400 women students, according to the late Margaret Berry, a former SRD resident turned UT dean, and author of Scottish Rite Dormitory at The University of Texas, A History: 1920–2007.

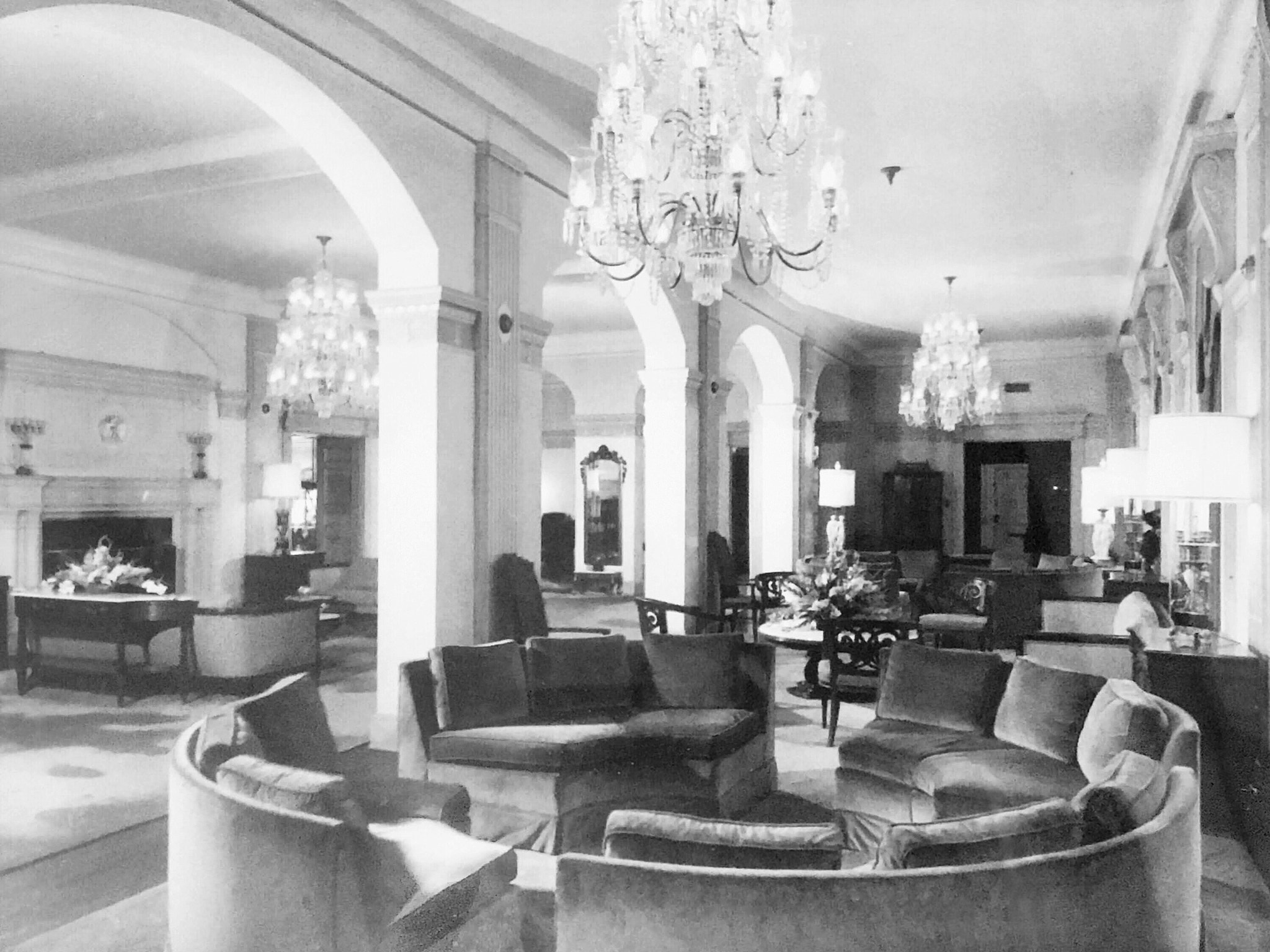

Berry, BA ’37, Life Member, Distinguished Alumna, also noted that when the Scottish Rite Bodies of the Masonic Lodge met in August 1920, they agreed to raise funds for two dormitories on the Forty Acres, one for men and one for women, where they could provide “a wholesome moral environment” for the budding scholars. It was also designed to be a home away from home for the young women, who weren’t really considered adults until they were 21. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were served daily, and residents were expected to show up for each meal dressed for the occasion. Curfews were strictly enforced and chaperone approval was required for almost everything. But the dorm was also set up to foster community and create an air of conviviality. The grand living room was designed to be just that: a living room where the women could visit and study and tell stories about their day, which is still how the room is used today. “It’s such a nice balance that we have,” Mazurek says of the SRD lifestyle. “We’re a great transition.”

Two years and $900,000 later, in late September 1920, SRD opened its doors (the proposed men’s dorm was never built). Room rates ranged from $10–$20 per month with a flat $25 monthly charge for meals. Upon completion, the five-story building had a formidable presence on what was then prairie land, and its rooftop was visible from blocks away. An undated photo of Hemphill Park, a residential neighborhood to the north, shows SRD towering in the background—an imposing structure more reminiscent of an English manor house than a Central Texas dorm.

“It was built for the daughters of Masons. You needed to be the daughter of a Mason [to live there],” explains Stone King of the original requirements for residents. Applicants were ranked in accordance with their familial tie, with top priority going to daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters.

Today, 100 years later, the question is still asked, though representatives say it’s not a factor in accepting new residents, a change that diversifies the applicant group and makes SRD a bit more accessible. “I would say [by] the ’80s it was slowly changing,” Stone King says. “[Diversity has] just become increasingly more important ... it is truly open to all girls because it is such a wonderful place, protected place, and a great launchpad for your career.”

Despite its efforts, SRD has hit some roadblocks on the path to inclusivity. In 2018, the dorm made national headlines when staff allegedly banned one of its residents from hosting her girlfriend. A “peaceful” settlement between the student, Kaj Baker, and SRD was reached the following year. Though terms of the settlement were kept confidential, Baker’s lawyer told The Daily Texan in 2019 that “increased education and awareness” at SRD was part of the deal.

In 1922, however, being the daughter of a Mason was still a requirement—and a point of pride for those who lived there. The dorm’s first residents were distinguished by their snappy SRD arm bands, a fashion choice that earned them the nickname “sardines” from other students. It stuck, and a century later, residents are still referred to by the nickname. According to Berry’s book, the first generation of sardines was subject to strict rules, including curfews, limited phone time, no meals in downtown hotels, and no unchaperoned nighttime car rides. The goal was not to cut off their social lives entirely, but rather guide them toward suitable matches and, hopefully, a husband.

In a Daily Texan article published in the late 1920s and reprinted in Berry’s Scottish Rite Dormitory, a student journalist documented a day in the life of the sardines, from the 6:30 a.m. wake-up call to the rush of women racing to beat the curfew at lights out.

“Things are quiet, except for one or two couples who are late and come running up the walk to the door where the girl is admitted and signs a card for the Dean of Women’s office, while the boy departs, thanking his lucky stars he’s not a girl,” the article reads.

Guiding the residents was a staff led by a director and assistant directors, known as chaperones, all women and almost all of whom were middle-aged and married. Though they maintained discipline, they were also beloved, and offered comfort and guidance for young women who were away from home for the very first time. They were known as the Matrons, and their domestic, mothering approach is still part of the SRD culture—perhaps the most important part.

“The staff … really truly care about every girl, even if there are 300 in there. They take care of you like that and they want you to feel like you’re at home in bed,” says Stone King, who later adds: “A lot of these girls share one legacy, and that is love. They are so loved.”

Maids, elevator girls, a gardener, chef, dietitian, and an onsite laundry team helped round out the robust staff, all of whom were overseen by a board of directors composed of Masons. Most major decisions—such as adding air conditioning (1955) and building a pool (1950)—were approved by the board, a hierarchy that still exists today, though Stone King says it’s morphed into more of a figurehead position.

There is, however, one job that was and remains strictly for the boys: waiting tables. In exchange for a free meal and a few other perks, male UT students, now mainly from a nearby fraternity, serve and bus dishes during meals for the female residents. The result is a kind of festive, flirty atmosphere, says Stone King, who happens to be married to a former waiter. (Their daughter, now in her third year at UT, is living at SRD.)

As the institutional hierarchy has changed over the last few decades, so too have the social aspects. Dinners requiring formal dress, sit-down Sunday lunches after church, and chaperoned dates have all given way to relaxed visiting hours for men and one single formal dinner held at Christmas. Other things have not changed. Chocolate Crumble Balls, or CCBs, are still a staple at every dorm event. (They will also be on the centennial party menu this fall.) Religion is still part of the cultural fabric, evident in wall hangings with calligraphed words like “faith” and voluntary morning meetings in the ballroom hosted by the Christian organization YoungLife. Residents still gather nightly on the round living room couches to study or play piano.

A sense of closeness is something Mazurek and her team work hard to cultivate, beginning with the resident questionnaire. Each year, about two-thirds of sardines are incoming freshmen, most of whom must be paired with a roommate. After nearly 30 years, Mazurek has developed a technique for making the best match, but says it often boils down to a single question about musical preferences. “You can learn a lot about [them] by the music they choose,” she deadpans.

Over the past century, SRD’s most substantial change has not come with the addition of AC (though surely that is No. 2), but with the emergence of women’s independence. Beginning in the 1980s, following the passage of legislation such as Title IX, there was a greater emphasis on women in academia. For the first time, women began to outnumber men on college campuses—a trend that continues today.

At SRD, that external cultural shift also happened to coincide with its de-emphasis on having a Master Mason on the family tree. “There’s a shift from what your husband accomplished—or that even that girls are there to get a husband—to now it is way more about the girls are there for themselves,” Stone King says. “The focus is on the girls’ overall successes themselves. And the dorm is extremely proud.”

Three decades into her tenure at SRD, Mazurek does indeed seem proud of her work and the thousands of students she’s helped guide as the dorm’s director. As she strolls down the hallway from her office toward the first-floor dorms she looks up at the newly painted walls and smiles. “The feeling of thousands of other women who have lived here—it’s magical.”

CREDITS: Illustration by Shout; Courtesy Scottish Rite Dormitory (6)