A New UT Research Center Is Looking Into How Psychedelics Can Help Those Struggling With Mental Illness

Marcus Capone felt beyond hope. He was having trouble sleeping and suffering from headaches, cognitive impairment, and depression. He turned to alcohol to cope, but that only exacerbated his symptoms. His wife, Amber, was at her wit’s end. They couldn’t keep going on like this.

Capone medically retired—what happens when a medical condition is deemed severe enough to interfere with proper performance of one’s military duties—after 13 years as a U.S. Navy Seal, and he had a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis—but no therapeutic treatments were helping. He and Amber suspected there was more to his diagnosis. It turned out Capone had a traumatic brain injury (TBI), likely sustained from his years of working as an explosives expert and his civilian days playing contact sports. TBIs commonly overlap with PTSD and sneak past without detection.

When their situation seemed most hopeless, Amber learned of ibogaine, a plant-based psychedelic used as a possible treatment for opioid addiction and other mental health maladies. She and Capone figured, what could it hurt to try? He traveled to Mexico in November 2017 to receive treatment, and came home to Texas not only healed, but passionate about helping other veterans receive similar life-saving remedies.

In 2019, the couple founded a nonprofit, Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions (VETS), which provides grants to U.S. Special Forces veterans to undergo psychedelic-assisted therapy treatment outside the U.S., and to receive preparation and integration coaching. Then in April 2021, Capone and Amber testified in support of HB 1802, a bill allowing for the study of alternative therapies for PTSD, particularly psychedelic therapies. In her speech, Amber credited the treatment Capone received with saving his life, their marriage, and their family. The bill passed on June 18, 2021.

The law’s passage has made psychedelic therapy research in Texas possible and led to the opening of UT’s new Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy, the first of its kind in the state, totally devoted to studying psychedelics for treating mental health disorders. Helmed by Charles B. Nemeroff and Greg Fonzo, the center is preparing to launch two psychedelic treatment studies—one for victims of childhood abuse, and one focused on veterans with PTSD. Texas has the second-largest veteran population in the U.S., and veterans make up about 7 percent of the state’s 18-and-older civilian population. There are 157,761 in Houston’s Harris County alone, according to data collected from the 2019 American Community Survey. Nemeroff and Fonzo are still fielding participants for the studies, and they receive daily emails from veterans who are desperate to take part, in hopes of finding some relief.

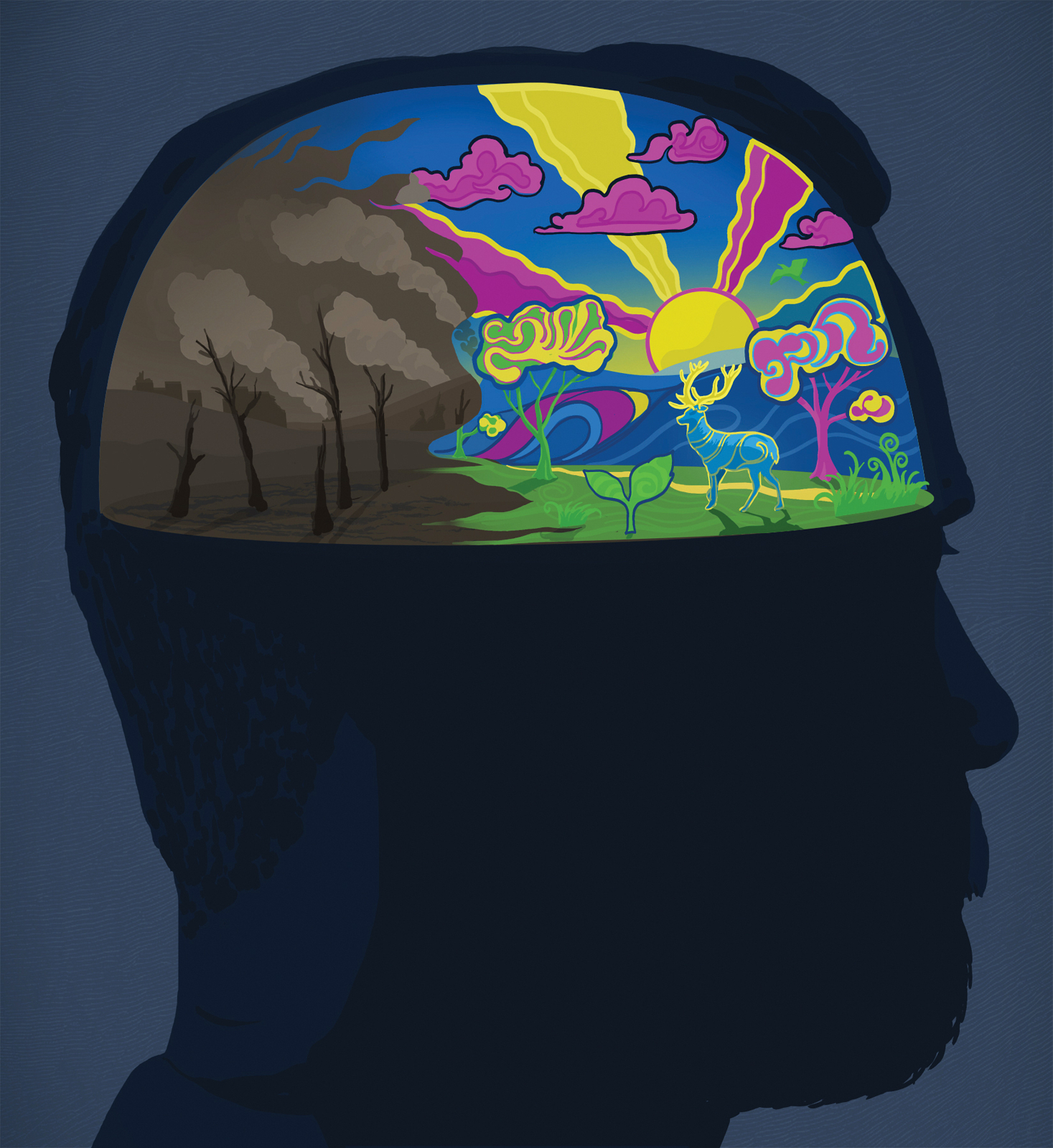

The veterans study will couple the psychedelic experience with subsequent psychotherapy. There will be someone in the room with them during the experience, and they’ll be listening to music, possibly talking about the things they’re seeing and feeling. Nemeroff and Fonzo think the psychedelics—specifically psilocybin in this case, colloquially known as “magic mushrooms”—will open the veterans’ minds to being receptive to the therapy, and perhaps other neuromodulation or even medications. The drugs facilitate fear extinction, meaning that certain triggers no longer cause fear or anxiety. They may also promote the growth of new nerve connections, enhancing the brain’s capacity for change. In other words, the trip they take on psilocybin could create a safe space for the mind to interact with traumatic memories, and help open it up to more traditional therapy methods like cognitive behavioral therapy.

Only a few hundred individuals have taken part in controlled trials with psilocybin. As a point of comparison, FDA-approved trials have thousands of subjects before medication is approved—so much more research is needed.

Throughout his career, Fonzo has worked with veterans at three different VA medical centers, and those experiences have broadened his perspective on what constitutes as trauma. When he was younger, he thought of trauma as a discrete experience, “where you have a life-threatening event and then shortly afterward, you develop some kind of symptoms in relation to it,” he says. “I think the veteran trauma experience is a bit different in the fact that it’s very repeated, and oftentimes very chronic kinds of issues, and sometimes the traumas are not necessarily their own lives being in danger, but losing friends or comrades, and the loss of the connection with that individual. And so there’s a lot of guilt, a lot of self-blame.”

His and Nemeroff’s approach is informed by the fact that this is a group of people that has suffered from issues that current treatments are not well poised to address: “chronic, repeated trauma, childhood trauma, combat issues, and traumatic brain injury comorbid with a lot of these conditions,” Fonzo says.

The Center is bringing scientific rigor to a field that hasn’t always been taken seriously. For a long time, psychedelics were classified as drugs of abuse. “They got bad press,” Nemeroff says. “And I think science is winning out where we’ll end up with these medications. ‘Who are they going to be helpful for?’ ‘How is it going to be regulated?’ ‘What’s the FDA going to do about this?’ is all open to question.”

“I’ve been following this line of research for over a decade,” says Fonzo, “and so I’m very excited. I never thought I’d be in this position, and I’m very happy to be here.”

CREDIT: Sam Falconer