The Ransom Center Spotlights the Women Who Helped Bring James Joyce’s 'Ulysses' to Life

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s revolutionary modernist novel, Ulysses. To celebrate, an exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center reexamines the book’s portrayal as the result of a lonely and underappreciated effort, and instead shines a light on the women who edited, funded, and championed the landmark work into existence.

Ulysses follows various subplots and characters on a single day in Dublin, Ireland, and was intended to serve as a modern counterpart to Homer’s epic Greek poem the Odyssey. Because of the novel’s innovative formatting and Joyce’s use of stream of consciousness writing, Ulysses is widely considered a masterpiece that paved the way for modernist progression in literature. But the exhibition, “Women and the Making of James Joyce’s Ulysses,” doesn’t dive deeply into the text and story of the notoriously hefty 18-chapter novel itself. Instead, it focuses on the infamous difficulties Joyce faced in finalizing the novel and seeing it through to its first publication in 1922.

As curator Clare Hutton aims to illustrate, Joyce wasn’t ever really in it alone.

Hutton, who specializes in 20th-century Irish literature at Loughborough University in England, says the exhibition aims to “engage broad, diverse, and intergenerational audiences, including anyone with interests in gay culture, feminism, the representation of female experience, Irish literature, and modernism.” Hutton was approached to curate the exhibition, which will be on display through mid-July, after her book, Serial Encounters: Ulysses and The Little Review, caught the eye of Ransom Center Director Stephen Enniss. Hutton’s book takes a studied look at the years leading up to the publication of Ulysses and works to “decenter Joyce from the traditional story of literary modernism,” Enniss says.

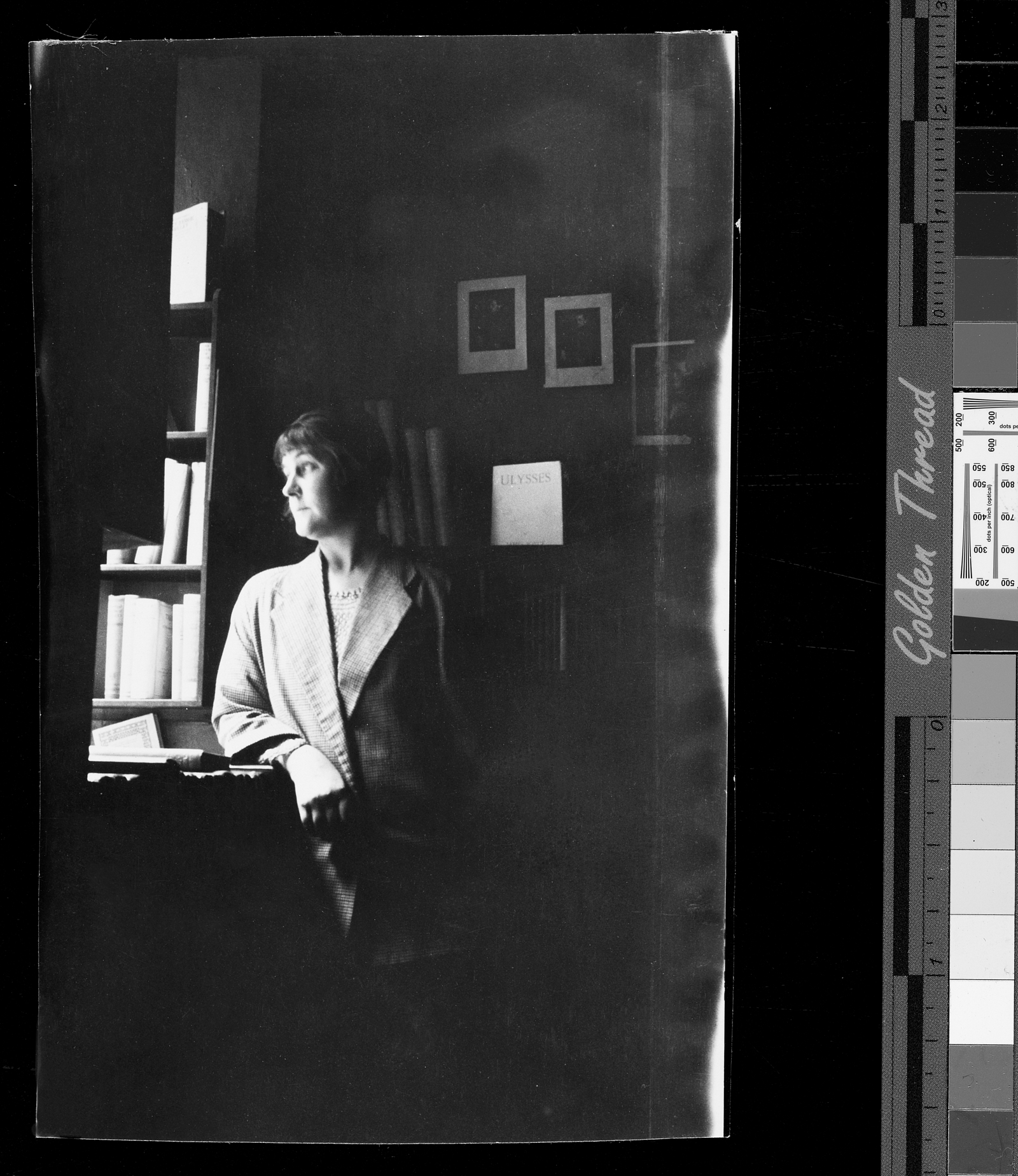

Utilizing the extensive Joyce holdings already housed at the Harry Ransom Center, including a mix of pictures, unpublished letters, notes, and other documents, “Women and the Making” counters the narrative that Joyce worked as a solitary genius.

“Books are inherently social,” Hutton says. “Joyce might have liked to cultivate the image of the lone genius in the Paris attic struggling with materials and circumstance, but actually the archives, the manuscripts, and the publishing history of this work tell a very different story.”

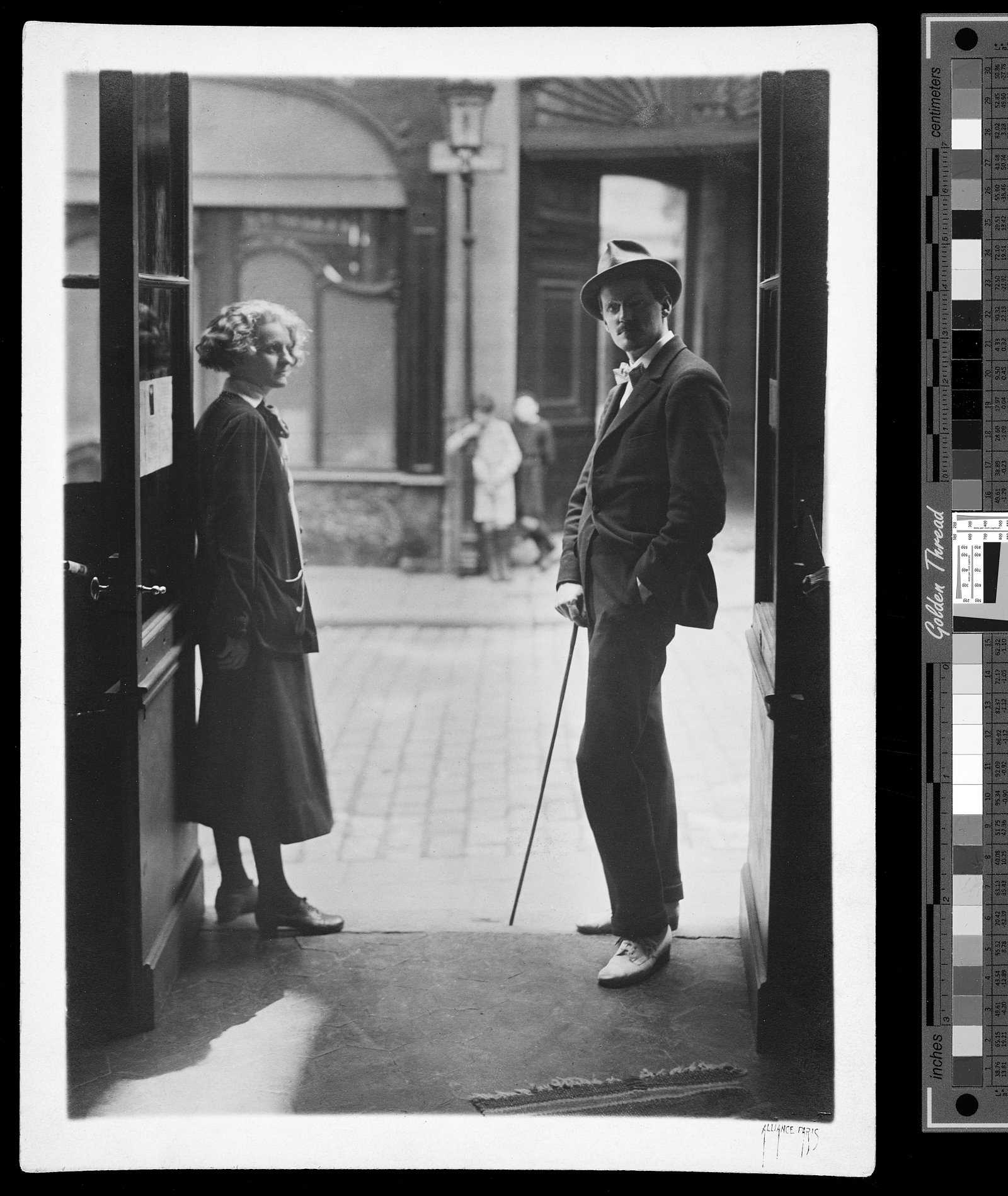

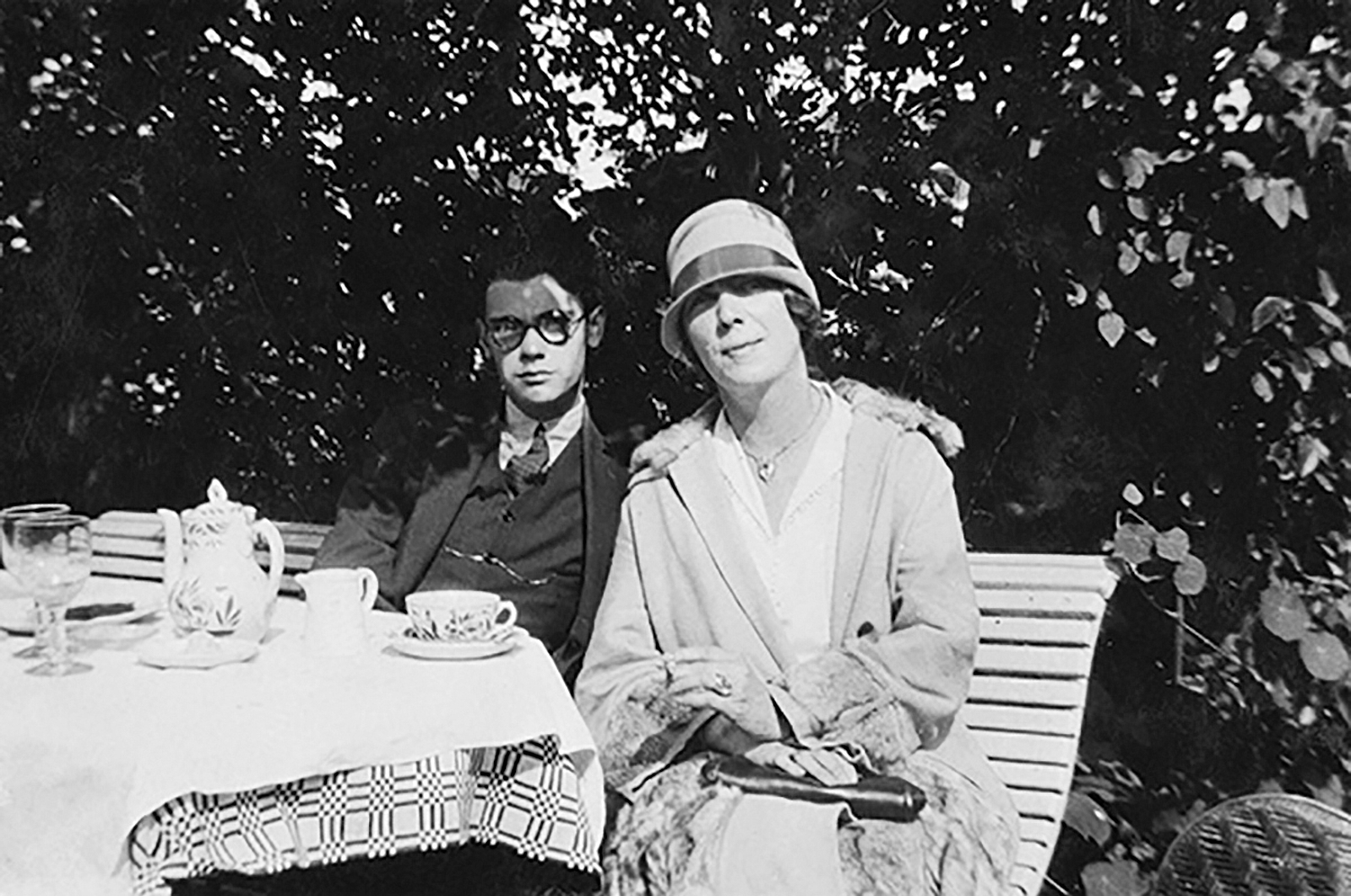

Most notable was a quartet of women involved in the book trade who offered Joyce support in various ways: publishers and editors Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap (who would eventually find themselves in court over publishing “obscene” portions of Ulysses); bookseller Sylvia Beach, the novel’s first official publisher; and Harriet Shaw Weaver, who offered Joyce steady financial support from 1916 and onward, without which Ulysses would never have come to be.

Anderson, Heap, and Beach were all openly gay American women, while Weaver was British, unmarried, and born to a wealthy heiress who allowed her considerable unearned income.

“Weaver, I think, is really one of the most interesting and important women behind Ulysses,” Hutton says. “The financial support really does enable the composition of the work, and Joyce’s complete concentration on Ulysses.” A year before the novel was published, Joyce wrote Weaver saying he was struggling to finish the novel “amid piles of notes at a table in a hotel” and against a “good deal of latent hostility towards the book among men of letters.” Hutton notes, in contrast, that Joyce was particularly well-supported at the time by those seeking to see the novel to the finish line and had a fair share of the book’s contents beneath him.

Although Joyce’s undertaking of Finnegans Wake would later strain his relationship with Weaver and cause the longtime working partners to almost entirely cease communication before Joyce’s death in 1941, Weaver reportedly stepped in to fund the cost of his funeral.

In New York, Anderson and Heap edited The Little Review literary journal and in 1918, agreed to serialize the novel in the magazine before the book’s publication. The serialization helped encourage and keep Joyce to a regimented writing schedule. The attention won by this serialization led publisher Beach to agree to both publish and sell Ulysses at her Paris bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. In a letter to her sister displayed at the Ransom Center, Beach correctly predicted the decision would “make [her] place famous.”

Speaking on an item in the exhibition that resonated most with him, Enniss singles out a photo of Joyce standing alongside the men often lauded as having aided in Ulysses’ publication: American poet Ezra Pound, lawyer John Quinn, and novelist Ford Madox Ford—who all edited early versions of the book for Joyce. The photo is noteworthy “for what it says about those who are not present,” Enniss says. Hutton makes a compelling point that the women who directly enabled the publication of Ulysses never appear with Joyce in such a way, underscoring the gender roles that governed literary production in the early 20th century.

While these four women played a crucial role in seeing Ulysses to publication, the exhibition also highlights the necessary emotional and personal support Joyce’s partner Nora Barnacle, his mother, and his Aunt Josephine provided him throughout his life. Letters between Joyce and his mother hint at their deep connection and are displayed alongside pages of Ulysses where her death is memorialized. “I am very interested in silent, underacknowledged labor, emotional labor, and psychological support. These kinds of support make a huge difference to people’s daily lives,” Hutton says of the women who supported Joyce in his personal life. “It is fascinating to make an exhibition which acknowledges what is so often and so easily overlooked: material and psychological support.”

While, according to Hutton, the exhibition serves only as a “suggestion” for contextualizing how Ulysses was published, she says there is no shortage of historical materials to back the postulation.

“You could talk about women in Ulysses forever,” Hutton says. “It really couldn’t have come into being had it not been for the tireless support of women who did so much to give Joyce material support and to keep on communicating confidence—the confidence they had in his ability. You can always see women facilitating that confidence. It’s an extremely deep and important history of support.”

Credits: Harry Ransom Center