UT Researchers Might Solve the Mysteries of the Universe With the Most Powerful Telescope Ever

There’s never been a way to clearly see the past here on Earth. Archeologists can uncover fossils and artifacts, geologists can analyze rock, and anyone can crack open a history book or look at an old painting. But none of these things show exactly what something looked like at that time.

That’s not the case when it comes to the work of Caitlin M. Casey, an associate professor in UT’s Department of Astronomy who looks into the past every day as an observational astronomer.

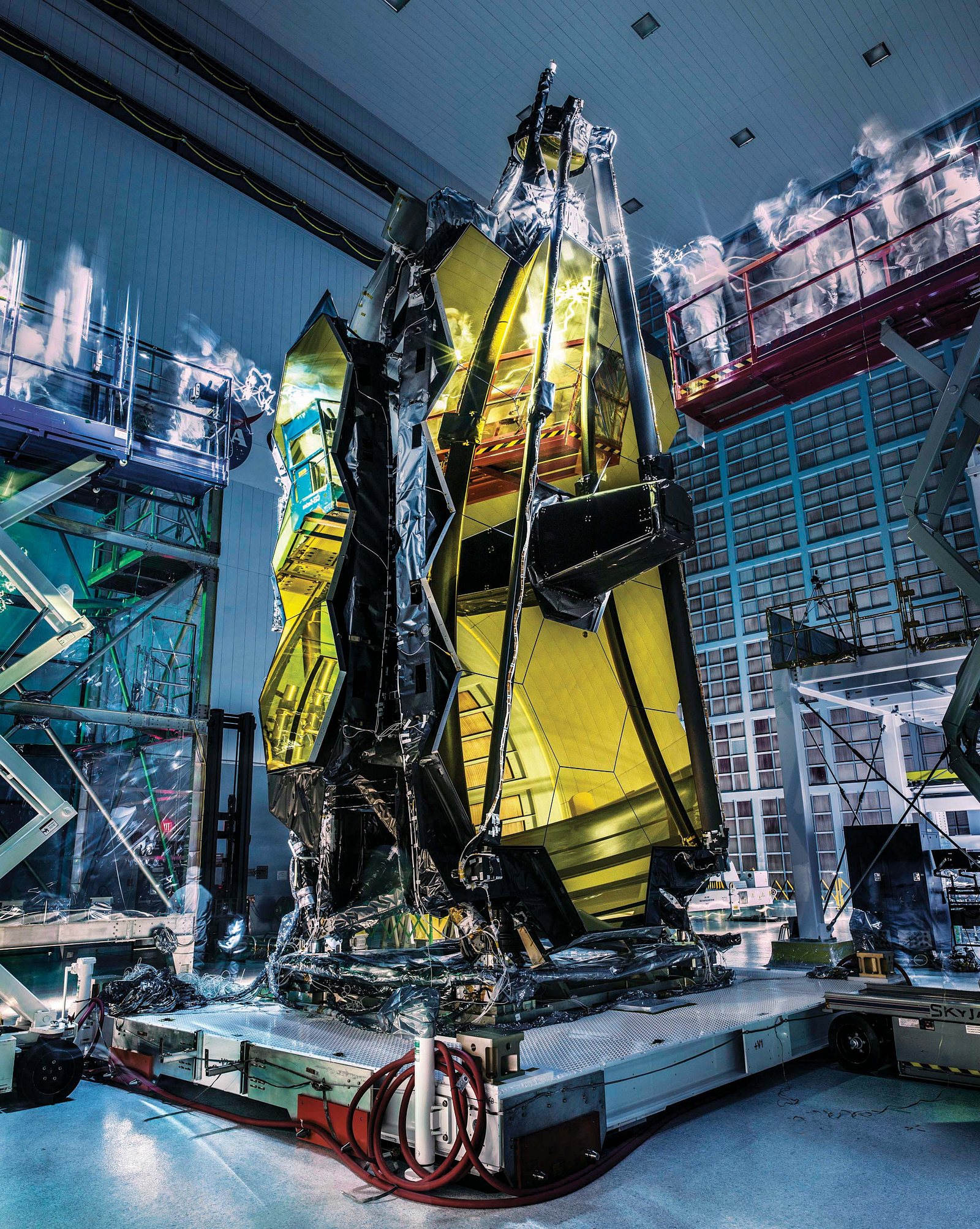

Casey is one of the leaders of a team of scientists across the world who will use the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope-—the most powerful space telescope ever built—to uncover secrets of our universe’s beginnings billions of years ago.

“When the first galaxies and stars turned on for the first time, there was a lot of mystery in the very first stages of the universe,” Casey says. “We’re basically trying to write the history books, going all the way back to the Big Bang.”

The findings from the James Webb Space Telescope—which Casey calls “the ultimate tool that astronomers have been waiting for, for decades”—are expected to be groundbreaking. From its point of view in orbit more than a million miles from Earth, the telescope will be able to capture images of space that are deeper, richer, and more informational than images from any telescope before it, including the Hubble.

Casey would know. She works with all kinds of telescopes across the world to decipher their images, gleaning information from what looks to others like a mosaic of dots, swirls, and pops of lights.

Now, her team has been granted a full nine days with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) for their project, COSMOS-Webb. It’s similar to the Hubble Deep Field project that captured images of the sky over 10 straight days in 1995, but COSMOS-Webb is even bigger and more ambitious.

“The Hubble Deep Field was roughly covering a patch of sky that is so small, it could be behind the head of a pin if you’re holding that pin at arm’s length away from you,” Casey says. “We’re covering an area equivalent to three full moons. That’s a sizeable chunk of the sky. We expect to find something like a million galaxies in the COSMOS-Webb image.”

With the nine days’ worth of images, Casey and her team will analyze the smudges of light in the background, not the big, beautiful galaxies that will be clearly visible in the JWST images. To us, those smudges may be more akin to dust on a screen, but to Casey, they are quite literally pictures of the past taken in real time, the galaxies that may or may not exist anymore still visible due to their light that has taken so long to travel to us. It also represents a full-circle moment for her—Casey was inspired to become an astronomer after seeing the Hubble Deep Field images as a child.

“I remember seeing these images and just being totally awestruck by how deep they were and how far they went, showing us objects that are further away than anything humans have ever seen,” Casey says. “I was just hooked. I got as many books as I could get my hands on and tried to learn as much as possible.”

Casey and her team’s time with the telescope won’t be until December 2022 or April 2023, when the telescope is in the position to get the images they need. But this is just the first cycle of research involving JWST. The telescope is expected to function for at least 10 years, which means we aren’t far from learning answers to some of the biggest questions on Earth: How did we get here? Are we alone?

“Even if [the telescope] were to last for [only] 10 years, we will be blown out of the water by the data that we get,” Casey says. “JWST will just revolutionize astronomy in many, many ways. And I think the entire community, and hopefully the world, is as excited about it as I am.”

Credits: NASA/Chris Gunn; NASA/Bill Ingalls