The Longhorn Who Brought Us The Oregon Trail Video Game Has Some Unfinished Business

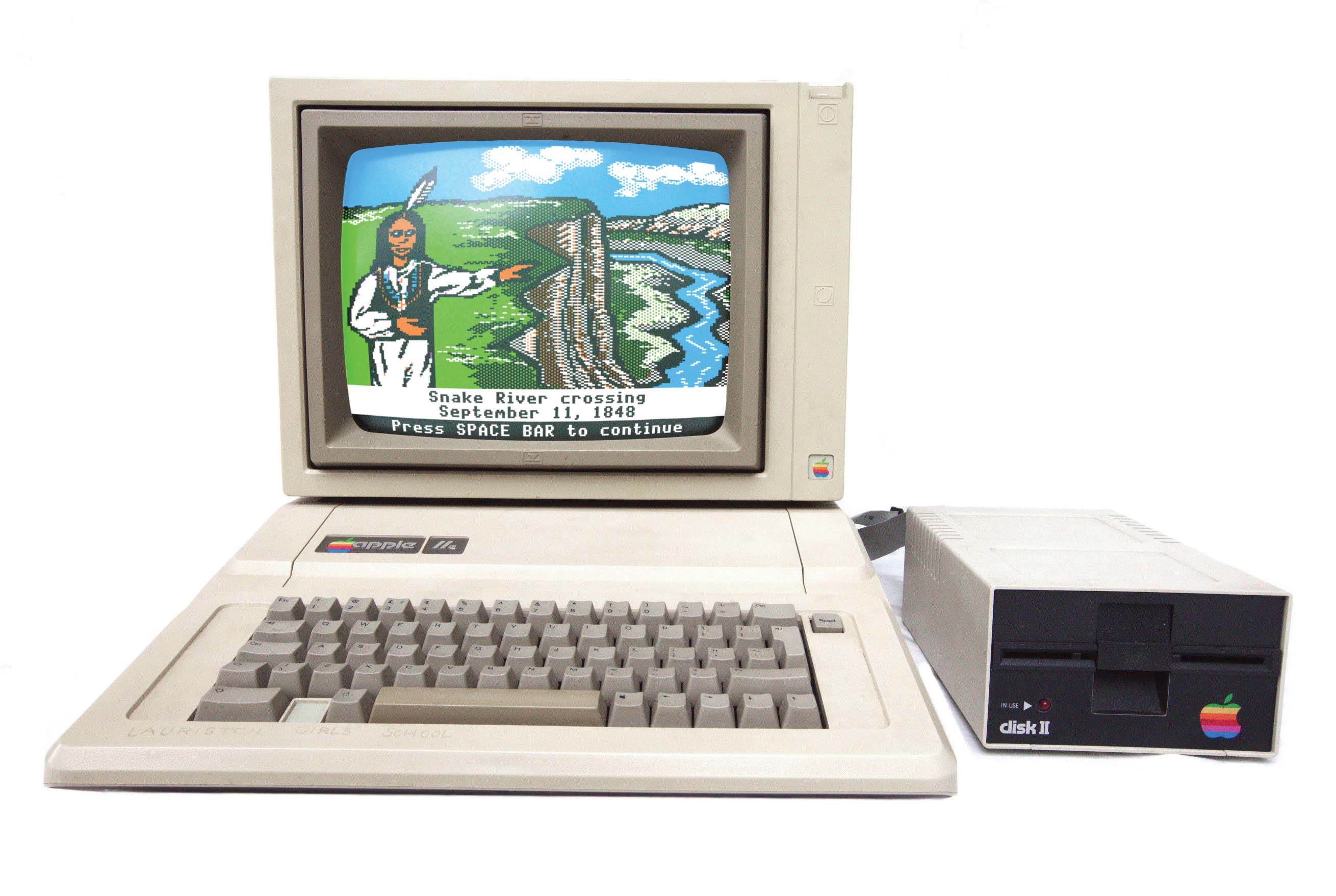

If you attended an elementary school in this country with a working computer between 1985-1993, there’s a rock-solid chance that you spent countless hours virtually hunting elk; unsticking a wagon after unsuccessfully fording a river; or dying of cholera, dysentery, or a number of other antediluvian maladies. For that, you can thank R. Philip Bouchard, MA ’79.

As an employee of Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC), Bouchard led a team that made the 1985 version of The Oregon Trail a household name. He did it all by combining his childhood love of nature with his passion for education and his eventual computer software skills. The path that led him to that adventure started in 1961, when the Apple II was a world away.

When Bouchard was in first grade, his parents bought him a book on identifying trees, kickstarting a passion for botany and natural exploration that would come to define his career.

“It was a little hard trying to tell the different oaks apart and the different vines apart, but still, it was fascinating,” he says. By the time he was an upper elementary and middle school student, he was leading nature tours around the forest for the other kids and looking for interesting plants and animals.

Bouchard eventually found himself at the University of Georgia, where he studied botany, obviously, with a specialization in plant ecology. But as a senior, about to graduate into an uncertain world, he did some soul-searching. He loved science, education, and, of course, science education, but he didn’t want to work in the classroom. He thought film might be cool, and maybe he’d eventually write some books, but computers were the newest frontier. He enrolled at the University of North Carolina in its formidable master’s computer science program, but after one year, he realized the program was pushing him in one, lone direction. For many computer scientists in the late ’70s, it was the dream, but for Bouchard, it was a dead end.

“It was taking me to work for IBM,” he says.

So he started looking around for schools that would allow him to synthesize his love of botany, ecology, computers, and science education. If the school also had a good film program—just in case—all the better.

The best match? “The University of Texas at Austin,” he says. He transferred in 1977, joining the botany department in the ecology group. Soon enough, he was allowed to start working with computers, creating computer simulation models that could be used for instructional purposes. Back then, Bouchard says, these models were created strictly for research. But what if he could streamline them and let non-science majors run wild in ecosystems and discover what happened for themselves?

“I decided I wanted to make my career in that area after graduating, but it took a little while to find a job,” Bouchard says. “It turns out I was ahead of the game. There were no professional jobs in computer-based educational software at that time.”

In 1981 he landed at MECC, a Minnesota-based educational software company, and soon after became acquainted with a historical simulation they had created called OREGON, a modified version of a game called The Oregon Trail created in 1971. His wife, Miryam, MA ’79, joined the company two years later, the same year that Oregon, as it was now named, had become the company’s best-known program. The only problem was, as computer technology rapidly changed, the mostly text-based game—a rudimentary deer hunting scene existed, but not much else graphically—was beginning to tarnish the company’s reputation because it looked so outdated.

“It was so crude-looking compared to what was then coming out, it was also too simple compared to what was then coming out,” Bouchard says. “It had been a highly innovative program when it was first designed in ’71, but it wasn’t in that category anymore.” In 1983, Bouchard was advocating that MECC create a new version. That following October, it got the sign-off, but with a caveat: They would make a new version, but it would be marketed for homes instead of schools. “It was a bit surprising, but I was happy to do that, and pleased when they decided to put me as lead designer and team leader,” he says.

Bouchard says his success in creating what Smithsonian magazine later determined was “a cultural landmark for any school kid who came of age in the 1980s or after,” was that crystallization of his interests that began way back in childhood. The gulf between the educational designers and the programmers was vast, and Bouchard knew how to ford it, as if he was one of his characters crossing the Snake River.

“I was the one person on staff who was familiar with pedagogical concepts, with teaching science education,” he says. “The programmers were all very young, almost all males who didn’t care about pedagogy; they cared about getting down into the guts of the computer. The two groups would talk past each other. I was the mediator; I was the one who understood what both sides were saying. I could call BS on either group.”

The game was simple but effective; players started in Missouri, as a Boston banker, an Ohioan carpenter, or a farmer from Illinois, and journeyed west toward the Willamette Valley during the 19th century. Along the way, players crossed major American landmarks, hunted for game, purchased goods, and tried to avoid the many pitfalls—the aforementioned diseases, plus drowning, dead oxen, and more—that the real-life explorers experienced while traversing the actual Oregon Trail.

Released in August 1985 for the home market, The Oregon Trail wasn’t available as part of MECC’s school software licensing program at first. Until that November, when the teachers revolted at an annual education conference and demanded Oregon Trail for their classrooms. Bouchard and MECC quickly reconfigured it with school market packaging and lesson-plan information for teachers and added it to the licensing program. Before long, it was the most common computer software program in North American schools.

In 2016, The Oregon Trail was inducted into the World Video Game Hall of Fame. Though officially all versions in the series are considered to be an iteration of the same 65-million-selling game, the 1985 version that Bouchard created no doubt is the reason for its introduction. It entered immortality in a wing of Rochester, New York’s Strong National Museum of Play on May 5 of that year, alongside all-time titles like The Legend of Zelda, The Sims, Sonic the Hedgehog, and Space Invaders.

“I thought that it would hang around for five years or so, and then the change in technology would make it obsolete and people would just forget about it,” Bouchard says. “I would never have guessed that, years later, people would still be talking about that ’85 version.”

Bouchard has made a name for himself as an idiosyncratic software guy—a polymath who managed teams with a combination of wit and grace but who was confident in his skills as a designer. Steve Taffee met Bouchard during his first couple years at MECC, and they have remained friends ever since.

“A lot of people knew Philip because he was a gregarious guy, also kind of a unique character,” Taffee says. In addition to relying on Bouchard for answers to questions about plants or animals while completing Oregon Trail, his former coworker says sometimes he’d just volunteer his ecological facts out of the blue. One time, while at an Apple conference in San Francisco, the MECC group were darting up and down the hilly terrain in an old, overloaded car, its springs sagging, causing the vehicle to scrape the pavement. As they bottomed out on one hill, Bouchard turned to his team and casually quipped: “This is like the black-footed ferret who drags his butt and marks his scent.” The group erupted in laughter.

Taffee wasn’t even on the trip, and he heard the story relayed over and over again for years.

“That’s Philip. He had the ability to entertain, which was one of the endearing things about him,” he says, “particularly in light of the fact that most programmers are not particularly extroverted.”

Despite his success, the industry changed drastically in the next decade-plus, and Bouchard left educational software in 1999. Miryam died from a stroke in 2009, during their 30th year of marriage. He remarried, to a woman he met while traveling in Australia, in 2012, but that marriage fell apart and he reconnected with a woman named Marsha, whom he had dated for a couple of years in the 1970s at the University of Georgia.

Retired now, he’s finally getting back to another idea he had back when he was an undergrad: writing science education books. Late last year his book, The Stickler’s Guide to Science in the Age of Misinformation: The Real Science Behind Hacky Headlines, Crappy Clickbait, and Suspect Sources, was published.

“The number one motivation was to share my love of natural science, [and] write about things that I thought people would find interesting or surprising,” Bouchard says. “I started focusing on misconceptions, and that led me to think about all the shorthand phrases that we use to talk about science and how these shorthand phrases and buzzwords are helpful in one way. It allows us to condense our speech, but it also tends to fall short in that now all these concepts are represented by one, two, or three words. We can easily build misconceptions around these short phrases.”

In his book, he breaks down 13 misconceptions we learn, from the long-standing teaching that the rainforest is “the lungs of the planet” (spoiler: they aren’t, really) to a final section that aptly breaks down epidemics and pandemics, and what we get wrong about them. In introducing concepts early in the book and connecting them throughout, Bouchard utilizes what he knows about science education and pedagogy to empty his mind to the next generation, much like he did 35 years ago with The Oregon Trail.

“I don’t want to write a book of trivia—‘1,001 interesting facts about science,’” he laughs. “I want to promote understanding—understanding of the world around us, the natural world. That includes things that we experience in our own house—the air and the sunlight, you know? What are the real basics? How can I make them understandable and how can I connect all those many dots?”

Credits: ShareAlike 4.0 International; Courtesy of R. Philip Bouchard