How Did Spoon Become One of the Most Enduring Indie-Rock Bands? It All Started at The University of Texas.

“On the Radio,” the seventh track on Spoon’s new album, Lucifer on the Sofa, feels like one of the more explicitly autobiographical songs in the Austin band’s extensive catalog, if only because frontman Britt Daniel, BS ’93, gives himself a rousing shout-out—including a first name he doesn’t use—in the opening verse.

“They say, how come you still play that game, John Britt?” Daniel sings. “Cause I was born to it/Yeah, I know I was born to it/And you know all I’m looking for ...” Bookended by both stately piano and slicing guitar atop the steady pulse of drummer and co-founder Jim Eno, the vocal drama builds to a falsetto. “On the RADIO! On the radio. They’re talking to me. All night. On the radio.” Like all of the best Spoon songs, it’s both minimalist and teeming with sound, hooky but not obvious, and doesn’t sound like anyone but Spoon—while still feeling completely fresh and new, a trick Daniel’s pulled off his whole career.

“On The Radio” is a song inspired by Daniel’s teenage years in Temple, Texas, where he found solace and excitement on the late-night airwaves, be it straight-up classic rock like Tom Petty and Kiss, or British bands like Julian Cope or The Cure. “That was sort of my lifeline to the outside world, the clock radio next to my bed,” he says. “Every night after the lights had to go out, I felt a lot less lonely because I had a radio.”

A few years later, Daniel would be playing records on the radio himself, holding down a very early morning shift on the cable-only University of Texas station that was then KTSB (it changed its call letters to the current KVRX—and got on the FM dial—in 1994). Soon after that, it would be his own music getting on the airwaves, first with Skellington, his college band, and then with Spoon. Nearly two decades later, you can still hear Spoon on KVRX, though probably not that often: As Daniel knows and appreciates from his own time as a DJ, the station’s mission has always been to play music that you can’t hear anywhere else—one of its slogans is “none of the hits, all of the time”—and these days, Spoon is just too big.

Not like, BIG big. We’re not talking Billie Eilish, Lil Nas X, or Tom Petty levels. But in the indie/alternative universe, the members of Spoon are giants. By being as good as it has for as long as it has, Spoon is the most accomplished band that Austin’s music scene, in its co-dependent co-existence with The University of Texas, has ever produced. You might not find Daniel flashing the hook ’em sign on TV at a football game, but he is right up there with Matthew McConaughey as a storied ’90s Longhorn. Some—OK, one or two writers—have even suggested Spoon will someday join Janis Joplin in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

“This is, very arguably, the greatest American rock band of the past 20 years, unyielding in their excellence, confounding in their consistency,” Rob Harvilla of The Ringer wrote of Spoon in 2017. And Lucifer on the Sofa, the band’s 10th record, released this February, is as good as anything the band has ever done.

“I could not be more biased, but I do believe Britt is one of the great rock/pop songwriters of his generation,” says Gerard Cosloy of Matador Records, which put out Spoon’s first album, Telephono, in 1996, then became its label again with the 2017 album Hot Thoughts. “He and Jim [Eno] have excellent ideas about how to work those songs into an ever-shifting and improving ensemble, and they have never phoned it in. They’re surprisingly open and curious about an ever-changing pile of musical influences.”

In many ways, that sense of adventure dates back to Daniel’s time in college radio, in an evolving Austin of the 1990s. “I learned about a lot of good music on the station and I learned a little bit of attitude from that station,” he says of KTSB. “I loved that they were set on playing music that you could not hear on any other radio station.” He remembers that one particular summer, even as Nirvana took over the Billboard charts, the most popular record at the station was a greatest hits set by Jamaican ska/reggae pioneer Desmond Dekker.

“They just liked what they liked,” Daniel says of his fellow DJs. And so it’s been for Spoon as well.

Daniel first arrived in Austin as an artsy, music-loving UT freshman. Growing up in the conservative town of Temple, he had a gut feeling music would be his life—but no idea how to make it happen. He played a little piano as a kid, then got a bass for Christmas around seventh grade and taught himself to play along to videos on MTV. “I would like, hum along to the bass lines instead of melody lines,” he says. You can hear that bass-forward mindset in Spoon to this day.

His neurologist father, who is also named John, told Daniel that the reason the Beatles and Bob Dylan were so good was because they wrote great songs. He remembers: “And then I started thinking about this thing that was a song, you know? And what makes a good song?”

He borrowed a friend’s acoustic guitar and started listening to records—by the Beatles, by Led Zeppelin, by The Smiths—over and over. “I’d play the record, and pick the needle back up and put it back down and put it back down until I heard what every string was doing. It was time consuming, but I had nothing but time,” he says. He wound up in a cover band in high school, the Zygotes, becoming the singer because no one else wanted to do it. Eventually they had a few originals, and even cut some songs at a real recording studio, owned by local legend Little Joe Hernandez (though their session was actually done on a four-track with Little Joe’s son, Ady Hernandez).

Daniel never really considered going to school anywhere else, which was as much about getting out of a place like Temple and into a place like Austin as it was about the education. “College was a way of biding time,” he says. “And getting my rent paid until I could figure out this band thing. This music thing.”

He and his friends had already come down from Temple every now and then for concerts, among them, Jane’s Addiction, The Smithereens, and Iggy Pop with the Ramones. And while he was too young to have experienced the city’s ’80s post-punk and “New Sincerity” scene firsthand, he’d seen the infamous 1985 episode of the MTV show IRS’s The Cutting Edge, which showcased all those bands. (Years later, John Croslin of Zeitgeist/The Reivers would wind up producing Spoon.)

“It looked like there was a scene down there,” Daniel remembers. “And it seemed like they were all hanging out at Mad Dog and Beans and Inner Sanctum.” Now he could hang out at those since-departed campus institutions and wander The Drag, where a 24-hour video arcade, bustling bus transportation, and diverse community all reminded him he wasn’t in Temple anymore. “It was like a whole other world for me,” he says. “Really an eye opener.”

Less fun (and less diverse) was his freshman living situation, at the private Castilian dorm. He’d expected to be matched with roommates who had similar interests, but wound up with the same sort of football-loving dudes he’d clashed with in high school. They were all pledging fraternities, and thought he was a hippie who did drugs (he wasn’t). “In retrospect, I would have fit in better at Jester,” Daniel says.

Where he did fit in was on the bottom floor of the Moore-Hill dormitory, where KTSB originally had its offices and studio. Initially a journalism student, Daniel had moved over to radio-television-film in order to do audio production (“I was like, Well, that’s the closest thing to making records”), and getting involved with the radio station just made sense.

The station was initially intimidating, which is a pretty common college radio experience—that fear that everyone grew up somewhere cooler and knows more about music than you do. “I remember walking in there feeling out of place,” Daniel says. “Feeling like everybody here must know each other.” But he eventually found his footing, starting out on production before becoming a DJ.

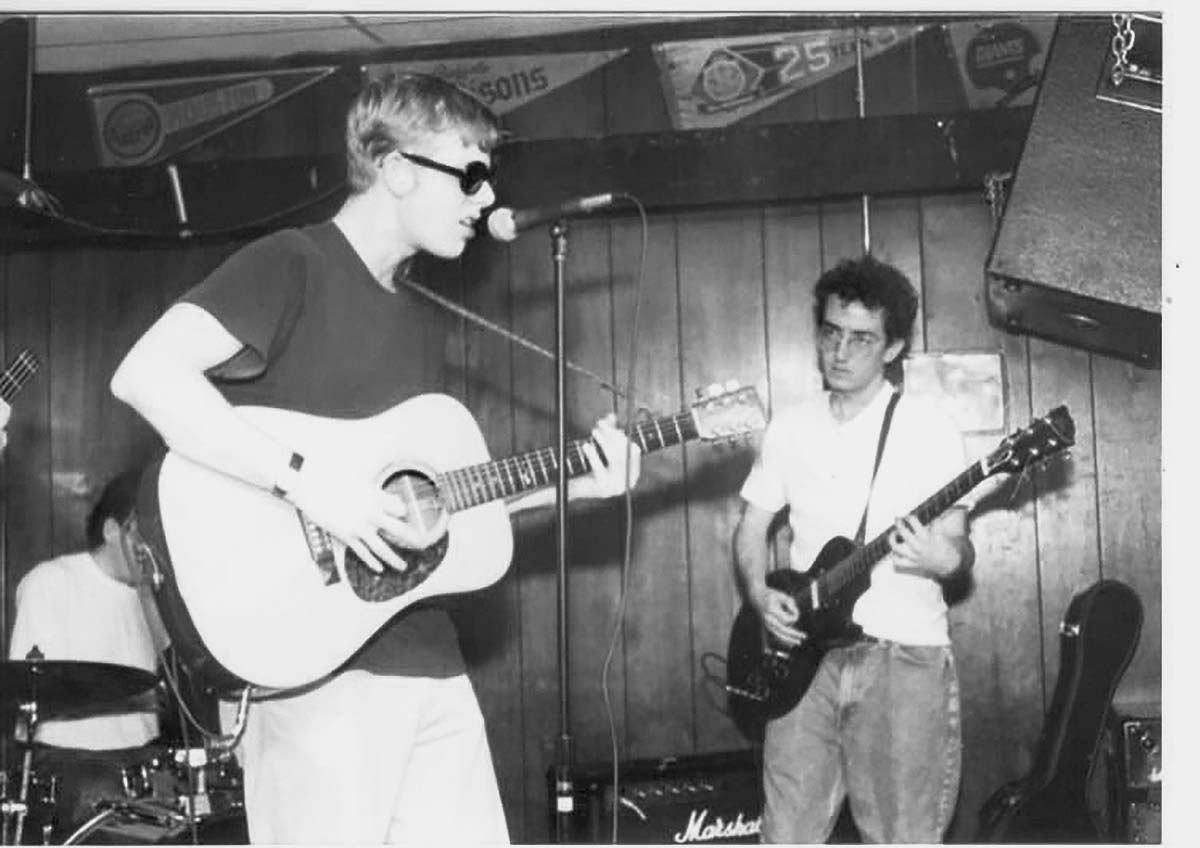

Daniel’s first Austin band, while still in college, was Skellington, formed with two friends from Temple, plus a guitar player they got by placing an ad in the Austin Chronicle. It was a good band, especially for a “college band,” with some of Daniel’s strengths—the voice, the ability to craft hooks—already on display. As Daniel remembers it, the two Temple guys were never all that serious about it, but he and guitarist Travis Hartnett, BA ’89, were—so much so that Hartnett eventually quit due to that classic line, “creative differences,” which is to say, he and Daniel didn’t get along.

After Skellington broke up in the summer of ’92, KTSB DJ Brad Shenfeld, who hosted the station’s blues show right before Daniel’s shift, but otherwise barely knew him, suggested Daniel join the country-influenced band he was trying to start. Daniel originally declined, but then reconsidered. Shenfeld, BS ’93, Life Member, still remembers how Daniel showed up for their first practice with a song that was so good he thought it was a cover. “I was amazed by his ability, especially taking into account that a few days prior he told me that he had no interest in country music,” he says.

The band that became known as The Alien Beats was short-lived, but it introduced Daniel to Eno, who had been their drummer. After graduation, Daniel got a job at Radio Shack (just long enough to inspire a Spoon song, “Don’t Buy The Realistic”) and then landed his first full-time straight job, at the Austin video game company Origin Systems, doing sound effects. It would also be his last, as Spoon were about to become the next big thing.

Sort of.

The legend of Spoon is that they were “discovered” by Matador’s Cosloy at South by Southwest in 1994. At that point they had one 7” single to their name, released by another former KTSB DJ, Naomi Shapiro, ’92, and the show wasn’t technically a part of SXSW—Spoon and myriad other local bands were on a bill at the Red River punk club The Blue Flamingo around the same time Johnny Cash and a new artist named Beck performed an official showcase at Emo’s down the street.

Cosloy liked what he heard immediately. “The songwriting felt fully formed and realized in a way that already had Britt in rarified territory,” he says. It would be another year or so before Matador signed the band—and they were not the only label sniffing around, it being the post-Nirvana, Lollapalooza, alternative rock-crazed ’90s.

But when Telephono came out in 1996, reviews and sales were not so good. Daniel’s songwriting may have been fully formed, but Spoon’s sound was still wearing influences such as The Pixies on its sleeve, and the record, while a huge favorite of Spoon’s local fans, is something of a distant memory for Daniel (it was not represented at all on Spoon’s 2019 greatest-hits set, Everything Hits at Once).

By the time Spoon hit the road with Telephono, the band had also made the first of many lineup changes, with guitarist Greg Wilson and bassist Andy Maguire leaving (Wilson amicably, Maguire not). Still a hot commodity with record labels, they wound up on Elektra for 1998’s A Series of Sneaks, which was both a creative breakthrough—with the band beginning to explore the boundaries of its sound while retaining a certain punk rock energy—and another commercial failure. They got dropped after four months, in large part, says Daniel, because the A&R rep who signed them, Ron Laffitte, quit. Instead of moping, Daniel took revenge by song, in the great tradition of artists such as Graham Parker (“Mercury Poisoning”) and Nick Lowe (“I Love My Label”). “The Agony of Laffitte/Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now” came out as a 7" on Bright Eyes’ label, Saddle Creek, and made Spoon something of a cause célèbre when they regrouped for their third album.

At that point, many bands would have gone away entirely. “But I wasn’t gonna stop writing,” Daniel says. “I was gonna keep trying.” And as Spoon got back to work on what became 2001’s Girls Can Tell, “we were also pulling it together musically in a way we never had before.”

When it comes to what makes Spoon so special, it’s impossible to separate out Daniel’s talent from his determination. “Britt is one of the hardest-working people I’ve ever met,” Shenfeld says. Daniel’s former Alien Beats bandmate originally came to UT as a member of Eddie Reese’s swim team, and is now a music and entertainment lawyer. His friend reminds him of the high achievers in both fields. “In my opinion, he is among the most talented songwriters that this world has ever produced, yet he works on his craft like a person who is obsessed with getting better,” he says. “I know he puts tremendous pressure on himself to outdo the last batch of songs every time he starts a writing cycle for the next album.”

Girls Can Tell was Spoon’s breakthrough album, kicking off a wave of creativity that saw Metacritic name Spoon its Artist of the Decade in 2010. Which is to say, Spoon’s four albums from that period—the others were 2003’s Kill the Moonlight, 2005’s Gimme Fiction, and 2007’s Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga—had the highest average review score of any band on the aggregation site, besting the likes of Outkast, the White Stripes, and Radiohead.

The spare, Prince-inspired “I Turn My Camera On,” from Gimme Fiction, is probably Spoon’s best-known song, in part due to its usage in a Jaguar commercial (it also wound up on The Simpsons). But every record has its bangers, from “The Way We Get By” to “Jonathan Fisk” to “The Underdog.” When Everything Hits At Once came out, it inspired countless articles and playlists proposing an entire second (or even third) best-of record, as the catalog is just that deep, if not always as pop as radio might like. One of Daniel’s friends who’s also done radio promotion for Spoon teases him that one reason they aren’t huge is because he’s not prone to writing choruses—this is even true of “I Turn My Camera On,” which is basically one super-catchy repeated verse. But that friend is also a devoted fan who would never expect him to do anything other than follow his own artistic judgment—and that also goes for Matador.

“Radio people are looking for that thing where, yeah, it’s a big epic widescreen chorus—the chorus, that everybody can sing along to easily,” Daniel says. “But there’s plenty of great music and catchy songs and great singles that don’t do that. You don’t have to follow that formula.” Spoon is capable of making crowd-pleasers, but only while still pleasing themselves. Often the band’s records seem to be made in reaction to previous records—the deliberately dark Transference (2010) came after the soulful and poppy Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, while the raucous simplicity of the new record is in contrast to 2017’s deliberately experimental/electronic Hot Thoughts.

Girls Can Tell came out the same year as The Strokes’ Is This It and the White Stripes’ White Blood Cells. Spoon has never been as big as those bands, and in fact, still isn’t. But not being BIG-big has probably been a blessing for Spoon—they have never had that one hit to live up to, or casual fans to lose. Most artists from 1994 or 2001—or, heck, even 2004, or 2010—have passed into history, their better work behind them, with only breakups, comebacks, and reunions still ahead.

Not so with Spoon and Lucifer on the Sofa. Daniel still sounds as hungry and ambitious as he always has. If Spoon was just starting to pull it together in 2001, they still feel like a band that’s pulling something new together now. They may be too popular for college radio, but the iconoclasm of KTSB and Austin still runs deep in Spoon. They’ve never forgotten where they came from—and they like what they like.

Credits: Courtesy Oliver Halfin, courtesy Spoon, Chad Wadsworth