Novelist Sarah Bird's New Book Goes Back in Time to Dance Marathons and 1930s Galveston

Growing up, Sarah Bird’s fairy tales weren’t the usual classics. Instead, she was regaled with true-life tales from her mother—“who told the best stories imaginable”—about her childhood growing up on a farm in Indiana during the Great Depression. “It was a very dire time in our country’s history, and certainly in the life of my mom,” Bird, MA ’76, says. “But my mother had a gift for turning anything into a party.” One particular story she loved to tell was about the time a dance marathon came to their small farming community. Bird has been fascinated by this forgotten tradition ever since.

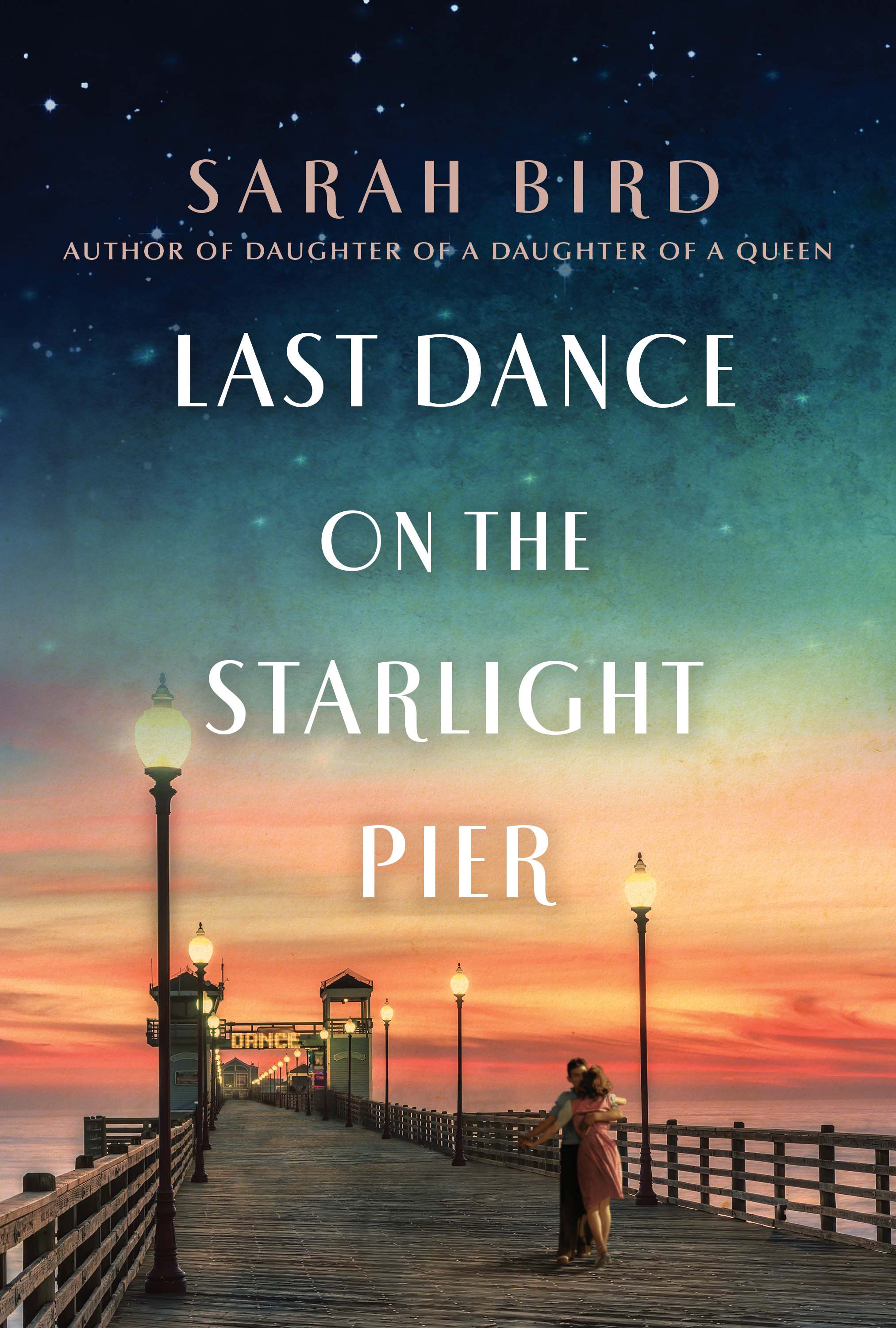

In her latest novel, Last Dance on the Starlight Pier (out April 12 from Macmillan), Bird brings that fascination to life, weaving the lively energy of dance marathons into the dark, complicated setting that was Galveston in the 1930s. Full of dynamic characters and the kind of brilliant, astute observations the 11-time novelist is known for, Last Dance on the Starlight Pier is a story about hope and love amid deeply difficult times. The Alcalde chatted with Bird about her research, her process, and why she thinks a nearly 100-year-old story—and tradition—will still resonate today.

Firstly, what were dance marathons? They’re not something we see very often nowadays.

They’ve kind of been forgotten for a number of reasons that fascinate me. But it was essentially … see how long people could last dancing. Some of the longest ones went on for months. The dancers would learn to sleep on their feet. My mother just made it sound like such a fun way to get together, very cheaply, at a time when nobody had any money and there were very few opportunities for socializing. She and all her friends went and got crushes on the cute boys who came from other towns, and brought picnic lunches. It was this great social affair.

What do you think was so fascinating to you about dance marathons?

I was always intrigued by the disparity between my mother’s memories, and then what was portrayed [in the grimness of the 1969 film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, which was centered around a dance marathon]. And then as I got older, even that memory sort of faded to the point where now, very few people have any cultural reference or collective memory of these dances. It was so fascinating to find out what an enormous phenomenon they were. At the height of their popularity, every city that had a population of 50,000 or more had a professional dance marathon. Some people have called them the first reality television. People who couldn’t afford anything else would go and sit and become involved in the lives of the dancers, watch them, cheer for them, bet on who would win, bet on who would drop out, and just have … a heck of a lot of entertainment for that time and place. To me, it’s a great tale of resilience and strength and of how Americans got through a really tough time.

You were writing this during another incredibly tough time—the beginning of the pandemic. How did that shape your writing?

It was a godsend, actually. It was fantastic to be able to have something to work on, to be able to escape into this totally different, completely absorbing world. I just find it very reassuring to think that we’ve been in dire places before, and we found ways—like these dance marathons—to raise everybody’s spirits and keep us moving forward. I feel like we’re at the same moment that they must have been during the Depression … We’re all thinking, Will this ever end?

You set the novel in Galveston, which has always struck me as such an innately literary place. Tell me about that choice.

Galveston is really the single most historically fascinating city in Texas. At one point they were the Ellis Island of the West—they processed [waves of] immigrants. Then the island was utterly flattened in [the 1900 Galveston hurricane]. And then these remarkable islanders jacked the city up 17 feet.

It sounds like something from fiction!

It’s such a world unto itself. The Amadeo family, [major characters] in my book, are inspired by the [true-life] Maceo family of Galveston, which began with two brothers who emigrated from Sicily. They were barbers who got into the bootleg business. From that they built an empire—they ran everything. They brought the biggest names in the world to come and entertain on Galveston Island. During Prohibition they had fleets of ships bringing bonded whiskey onto the island. It’s just such a contrast. The rest of the country was in bread lines, and they were living it up with champagne cocktails and long cigarette holders.

You do a lot of research in your writing process. How do you then figure out where that line is, between fiction and the history you’ve learned?

It’s a dance, honestly. I do enough research to know the world and to create chronological guidelines, and then within that, I’m very careful not to let the research impinge on the human story I’m telling. You know what’s interesting? How tough it is for readers to understand a past reality.

Say more about that.

Why a character would or would not do something that [the reader] would do. And just to understand the historical restrictions of a time. Especially in this novel, that was something I paid a lot of attention to: helping the reader understand the confines of this historical period.

So essentially, to make them more reliable narrators by giving the historical context?

Exactly. And to allow the reader to empathize with the choices they make, which would not be the choices a person of our era would make. And then to be able to make the distinction that by presenting these choices, I’m not necessarily defending them.

Your first four novels are contemporary. Why set this novel in the past, versus say, the similarly dark and resilient times of the modern day we’re living through?

I think there’s a fascination at an earlier age with our own selves and our own world, and the big questions are: What’s going to happen next? Where is this leading to? And then at some point, you look at yourself and go, OK, we’re dealing with a finished product here. I think it’s not unusual for someone to lose their fascination with their own particular selves and their immediate world, and to start wondering … How did we get here? And I think at that point, historical fiction becomes more interesting.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Credit: Julia Robinson