The Blanton Museum Is Featuring More Works by Black Artists Than Ever Before in Its Permanent Collection

The way the Blanton Museum of Art came by the paintings, sculptures, and installations that make up one of its current exhibitions is an anomaly for the institution.

In fact, Blanton curator Veronica Roberts stresses, the genesis of “Assembly: New Acquisitions by Contemporary Black Artists” is an extremely rare occurrence that the museum has previously not seen to this extent. “It’s kind of a wonderful story,” she says.

The exhibition, on display in the museum’s Huntington Gallery through May, features 19 works by 12 Black artists in a multitude of mediums and constructions. “Assembly” visitors can see paintings rendered in pastels and acrylics, yes, but also a piano outfitted in hundreds of house keys by artist Nari Ward that’s paired with a video depicting Black cultural traditions in Savannah, Georgia; a fabric-based sculpture by artist Kevin Beasley made of artfully piled scraps of durags and kaftans; and a flashing neon sign by artist Cauleen Smith that reads alternately “I will light you up” and “I will light up your life,” illuminating the words Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia said to Sandra Bland during the traffic stop that led to her death in police custody juxtaposed with lyrics from Debby Boone’s 1977 song, “You Light Up My Life.”

All the featured pieces were acquired by the Blanton thanks to a single anonymous donor looking to expand the museum’s collection of work by Black contemporary artists.

“She wanted to be anonymous because she wanted it to be about the artists and not a celebration of her gift,” says Roberts, whose curation efforts focus on acquiring new modern and contemporary pieces for the Blanton. “That was a very sincere gesture that I thought was quite wonderful and unusual.”

The donor had no ties to Austin or the Blanton Museum prior to her donation. But she did have an objective—to help highlight and celebrate the work of Black artists. She was looking only to fund, not select, acquisitions that would help diversify a museum’s collection. While she had originally planned to meet with a series of museums to determine where her gift should go, it took only one visit to the Blanton and a conversation with Roberts and Director Simone Wicha to finalize her choice.

According to Roberts, it was one piece in particular that spurred the donor’s decisiveness.

“We’d acquired this really amazing portrait of Madam C.J. Walker made from hair combs. It’s become really iconic in our collection,” she says. Walker was a Black woman who developed a line of hair care and cosmetic products in the early 1900s for Black consumers. She is also famously known for being the first woman to become a self-made millionaire. “[The donor] happened to know that piece and really love it, and to see that this was the kind of art we were acquiring sort of confirmed her impression.”

The piece, by artist Sonya Clark, was acquired in 2016 through a credit line that “reads like a novel,” Roberts laughs, with “a couple $500 donations here, a thousand or two there ...”

This sort of crowdsourced funding is the norm for the Blanton in adding to its permanent collection: Take what you can get, where you can get it, and amass it until you can purchase something. But with the freedom that the anonymous donor’s large annual donations ($200,000 every year for three years) and her hands-off approach to art selection allowed the museum, it’s enough to see why Roberts is so excited.

Although she shies away from naming a favorite piece in the exhibition, Roberts takes her time in describing the movement, celebration, and unease captured by artist Emma Amos in her 1983 piece “Hits.” Made from a mix of acrylic paint and handwoven fabrics on an oversized canvas with an unfinished hem, “Hits” shows two Black figures running—whether in victory or fear, it’s unclear. An initial glance might stir imagined home-run hitters rounding the bases, but sit with the piece a little longer and a threat takes shape just outside the canvas’ frayed edge.

“It’s a very ambiguous and, I think, powerful image,” Roberts says. “It makes you think of the way Black athletes are celebrated but also exploited.”

With “Assembly,” Amos, who died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease in 2020, is featured in the Blanton for the first time. All but one of the featured artists, in fact, are novel additions to the museum’s collection.

“It’s about time,” says Austin-based and East Austin-born artist Deborah Roberts of the Blanton’s effort to grow its works by Black artists. Deborah Roberts, whose renowned collage work is featured in museums worldwide and often addresses race, beauty, and gender norms and their deviations, has two other works in the Blanton’s permanent collection. With her piece “That’s not ladylike no. 1,” exhibited in “Assembly,” she’ll now have a third.

The mixed-media collage depicts a young Black girl wearing a Hello Kitty shirt with her nails painted red and sporting a sweet but knowing smile. Like many of Deborah Roberts’ pieces, the girl is backgrounded with an empty white canvas, a stark contrast to her painted skin’s rich tone.

“Having works by African-American artists is so very important,” Deborah Roberts says. “It’s important for people to be able to see themselves in these spaces of honor. When you don’t have that as a Black person, especially as a child, you don’t know where you fit and who you are. How do you fit in society if you never see your face on the walls of these types of white cube institutions?”

For one Black Austin resident, “Assembly” will bring that representation to life in its most literal form.

“One of the faces I’ve used in my work is of a little girl who lives in Austin. I always tell her that she can go up the Blanton at any time and see her little face,” Deborah Roberts says. “That’s the idea of being present in these really unique spaces come to life.”

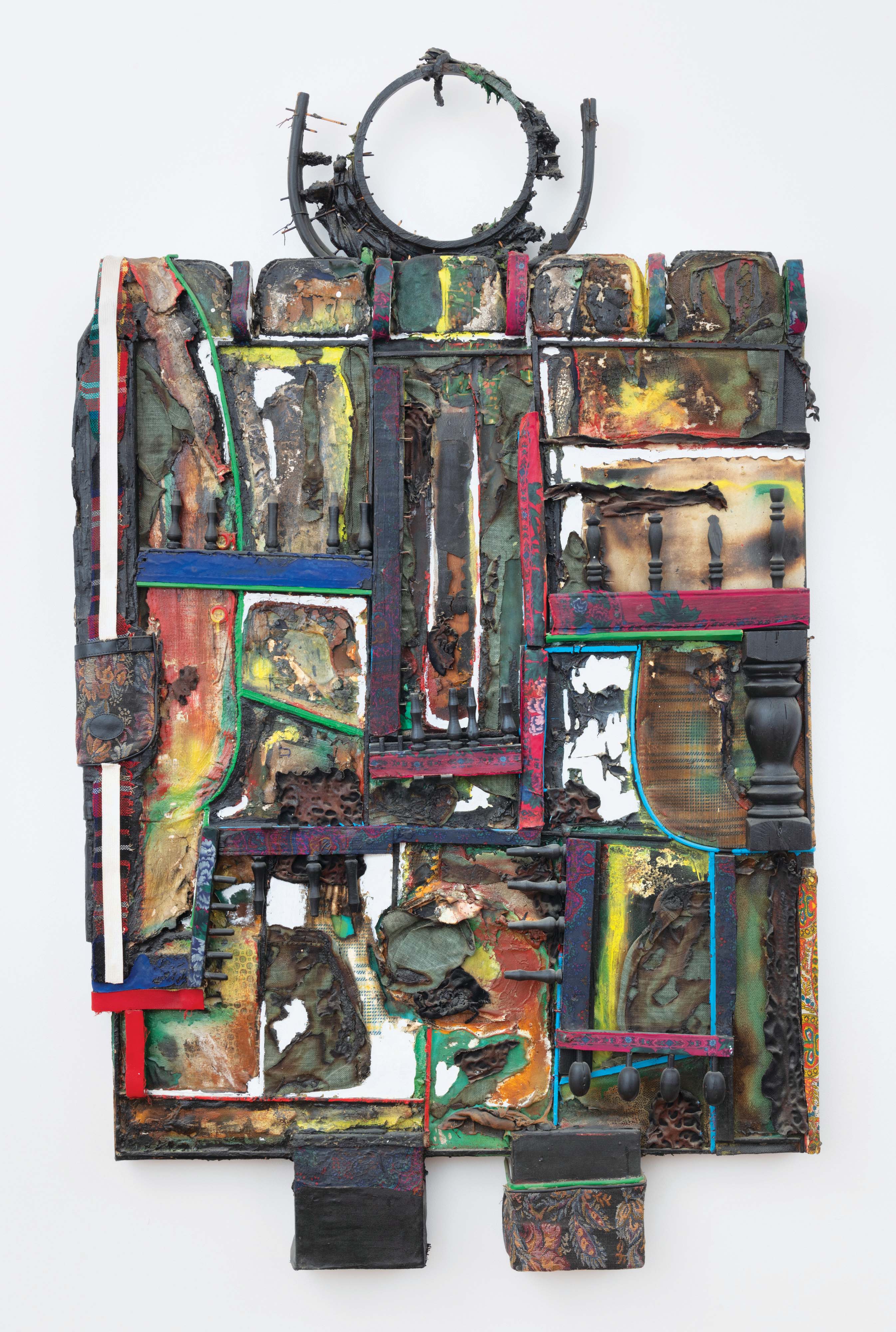

Credits: Noah Purifoy Foundation 2021, courtesy Jack Tilton Gallery, New York; Emma Amos, courtesy RYAN LEE Gallery, New York; Max Yawney, Nari Ward, courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London