Alice Embree, who Helped Integrate UT, Talks About a Transformational Time in U.S. History

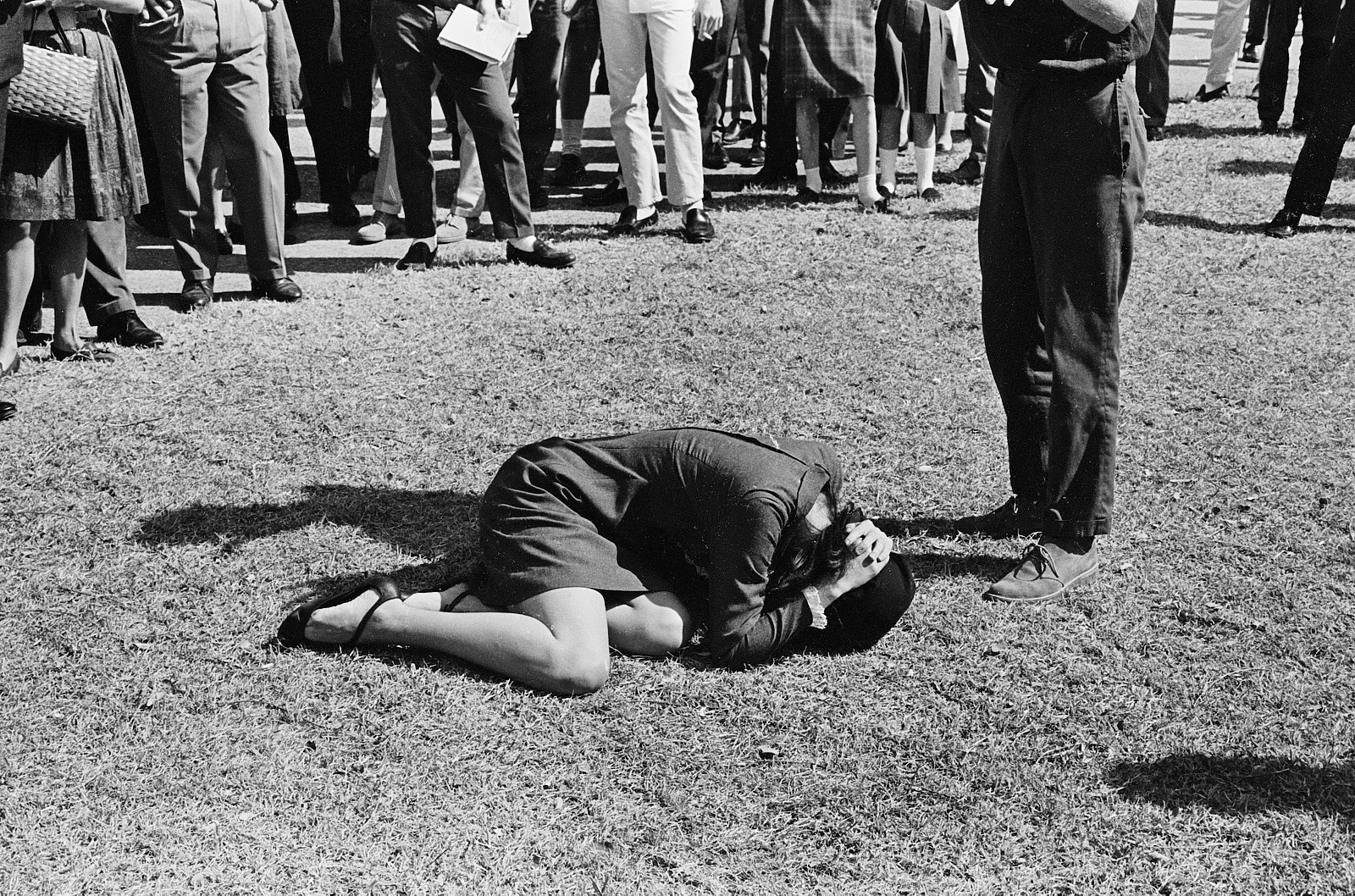

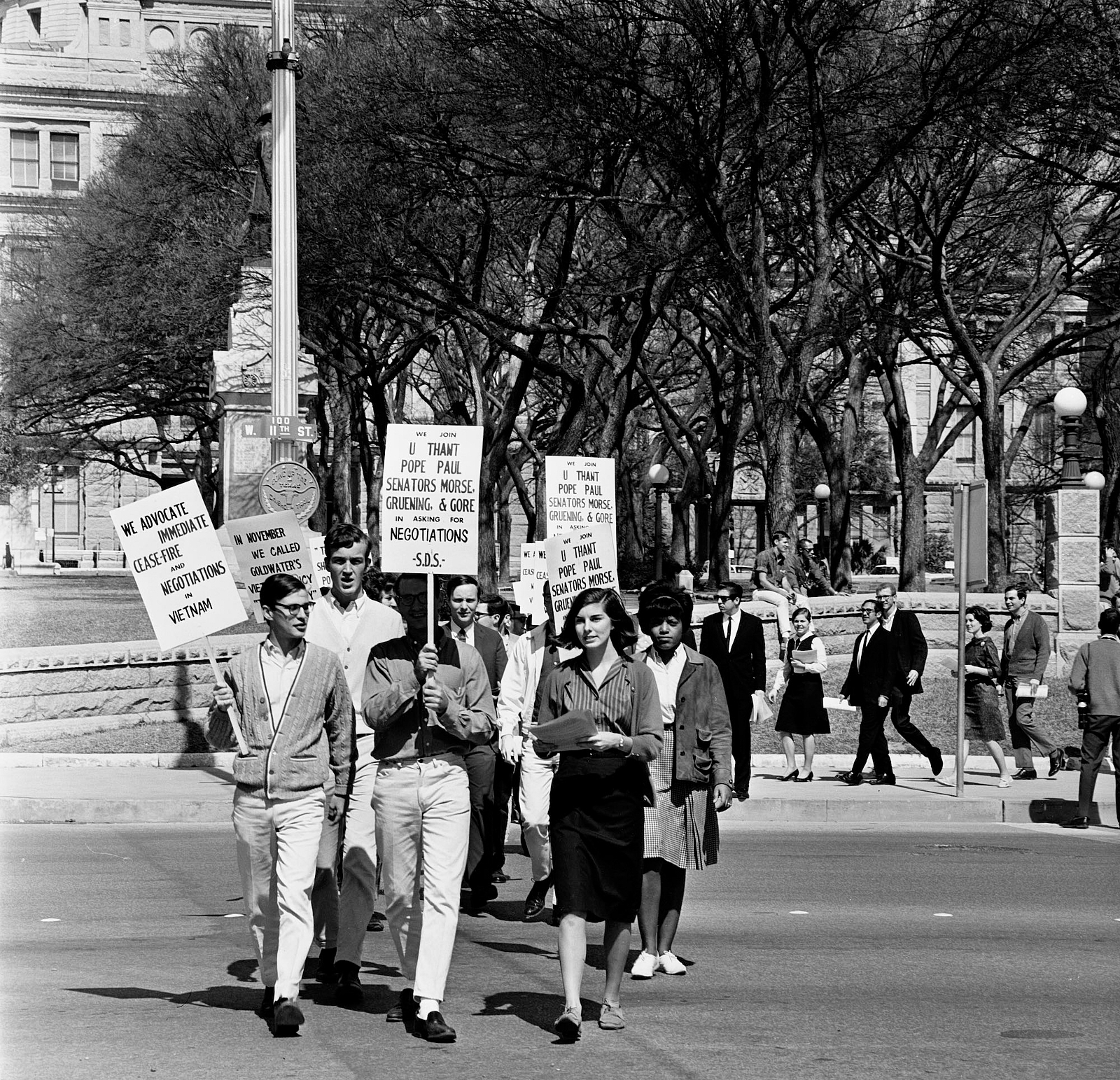

When Alice Embree arrived on the Forty Acres in the fall of 1963, UT dorms were still segregated. President Lyndon Johnson’s daughter, Lynda Bird Johnson, was living at Kinsolving—a fact UT’s inter-racial committee knew would be controversial—and Embree and others gained national attention demonstrating in front of the segregated dorm. By the spring, LBJ was delivering UT’s commencement speech and the dorms were integrating.

“A lot of students at UT now are shocked that somebody who is still living remembers this,” she says, “because it seems very distant.” Which is why Embree, 76, was driven to tell her story.

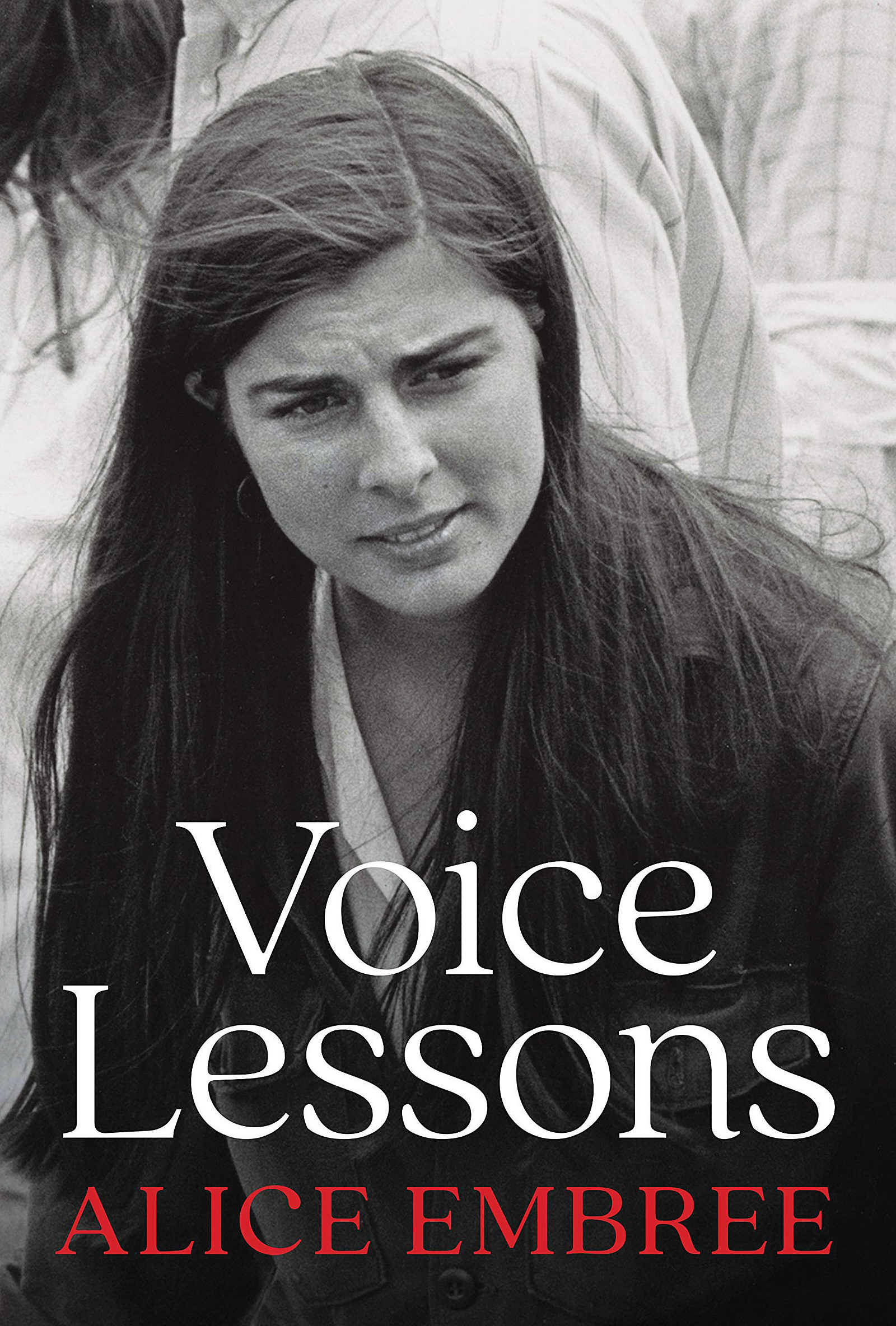

In her new memoir, Voice Lessons, Embree, BA ’82, MS ’87, shares her experiences as a lifelong activist—from growing up in a Jim Crow-era Austin and her time at UT to living in New York in the late 1960s, Woodstock, and her travels to Chile, Cuba, and Mexico.

The Alcalde chatted with Embree about social change, the women’s liberation movement, and finding her place in all of it.

Why did you decide to tell your story?

Well, it is my story, but it’s also the story of the movements for social change in the ’60s and ’70s. They had a transformational impact on my life and on the lives of many other people. I didn’t want that history to be lost. And I wanted to tell it from a woman’s point of view—and from the point of view of a Texan, because so much of that history is told on the East or West coasts, and it was different here.

What made it different here?

Maybe this is the culture of a state like Texas, but a lot of people came from smaller towns or other places, and in the ’60s and ’70s, the radical nature of politics mingled quite well with the counterculture. I mean, if you had long hair, you were treated like dirt, whether you had radical politics or just had long hair. It seemed to bond people together. Austin was special in that way, Austin being “weird.” There’s a Texan thing, too. Texans would go to conferences, we were sort of larger than life. The guys would have on black cowboy hats, they’ll be sitting there with Harvard grad students who would be like, Why did they let them in? [Laughs.]

What makes Austin continue to be unique city for activist work?

There’s a lot of hype about Austin being such a precious, progressive place. I think I, probably along with others, contributed to that hype. [Laughs.] But as a professor at UT [Eric Tang] studied, this is the fastest-growing city with a declining Black population. So I think that’s the problem with the hype—whatever change has to happen, it has to be multi-racial, multi-ethnic, it has to involve people from the working class, not just the professional class. It’s easy to go, “Oh, aren’t we cool?” But the truth is we’re just displacing huge populations with housing process. I just think sometimes Austin needs to take a good, hard look at itself.

What is your advice for UT students now who are working toward social change?

It’s a marathon, not a sprint. And anything you do is going to require sustained organizing and getting out of your comfort zone and talking to people. If you can build community and solidarity, that’s going to sustain you for life. And then I think it’s the ability when you don’t have success to drop back, rethink it, try again. I was naive as an anti-war activist. I thought, Well if we just say that the war is wrong, certainly we can stop it. And that wasn’t true. It’s a lifelong learning process. It’s not easy, but it’s worth it.

A lot of young people are overwhelmed by what feels insurmountable. What would you say to students who aren’t feeling hopeful about the future?

How do you stay hopeful? I think that’s about building community and spaces of solidarity. As an organizer, you try to find those things that connect, that people feel a need to do something about, and then in those spaces, you try to build a sense of solidarity, and if you think, for one minute, that elections are going to solve everything, then you’re probably wrong.

Through the process of writing, did you come across anything that you see through a different lens?

I feel that often this period gets written about by men and not by women. I wanted to tell the personal with the political. And particularly the part about the revelation the women’s movement was to me. In 1970 in Austin you couldn’t be a firefighter if you were a woman, you couldn’t be a bus driver, you couldn’t splice cables for Southwestern Bell. Everything was a mini battle. And all of these advances that maybe people take for granted now were won through various struggles. I think this generation has a lot of advantages with better process—and I think the women’s movement contributed to that.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Credit: Sarah Lim, UT Texas Student Publications Photos, Briscoe Center for American History (2)