A Glimpse Into the Life of Trailblazing Architect John Chase

John Chase was a man of firsts. He was the first Black graduate student to sign enrollment papers at UT Austin. Chase was the first licensed Black architect in the state of Texas and the first to be admitted to the Texas Society of Architects. And, Chase, MArch ’52, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, was the first Black president of the Texas Exes. Those accomplishments, immeasurable in their own rights, represent a mere fraction of his pioneering life.

That’s because to so many more—his family, the architecture community, the cities of Houston and Austin—Chase wasn’t just at the forefront; he was transcendent. While he wasn’t properly recognized for his immense body of work during his lifetime (he died in 2012, at the age of 87), a new reckoning of his importance began recently with UT architecture professor David Heymann co-authoring John S. Chase—The Chase Residence, an examination of that first modernist building in Houston.

And now, Tara Dudley, a lecturer at the UT Austin School of Architecture who attended graduate school with the help of the John S. Chase Scholarship, is working on the first biography of Chase. “He is so important,” she says. “I want to put everything into the book, but I also realize that I could work on this for probably 10 years and not be satisfied.”

The following images aim to convey a sense of the inextricable in these facets of that momentous life: his work, his community, and his family.

John Chase was the first Black graduate student to sign enrollment papers at The University of Texas, on June 7, 1950—just two days after the Sweatt v. Painter ruling came down from the Supreme Court. “He was very humble about the whole ordeal, really, without making it seem like an ordeal,” Dudley says. “Because surely there were things that he was going through personally, mentally, emotionally on this occasion. But I think for him, it was just achieving a step toward that broader goal of becoming a licensed architect.”

John and Drucie Chase at the plaque designating UT’s Heman Sweatt Campus in 1988. “They definitely had a respect for one another,” Dudley says. “Chase realized that were it not for Sweatt, he would have never gotten into UT. He said in interviews that had the case been Chase v. Painter, he probably would have been the one who never graduated from the university because he was the public face of this very important event in history.”

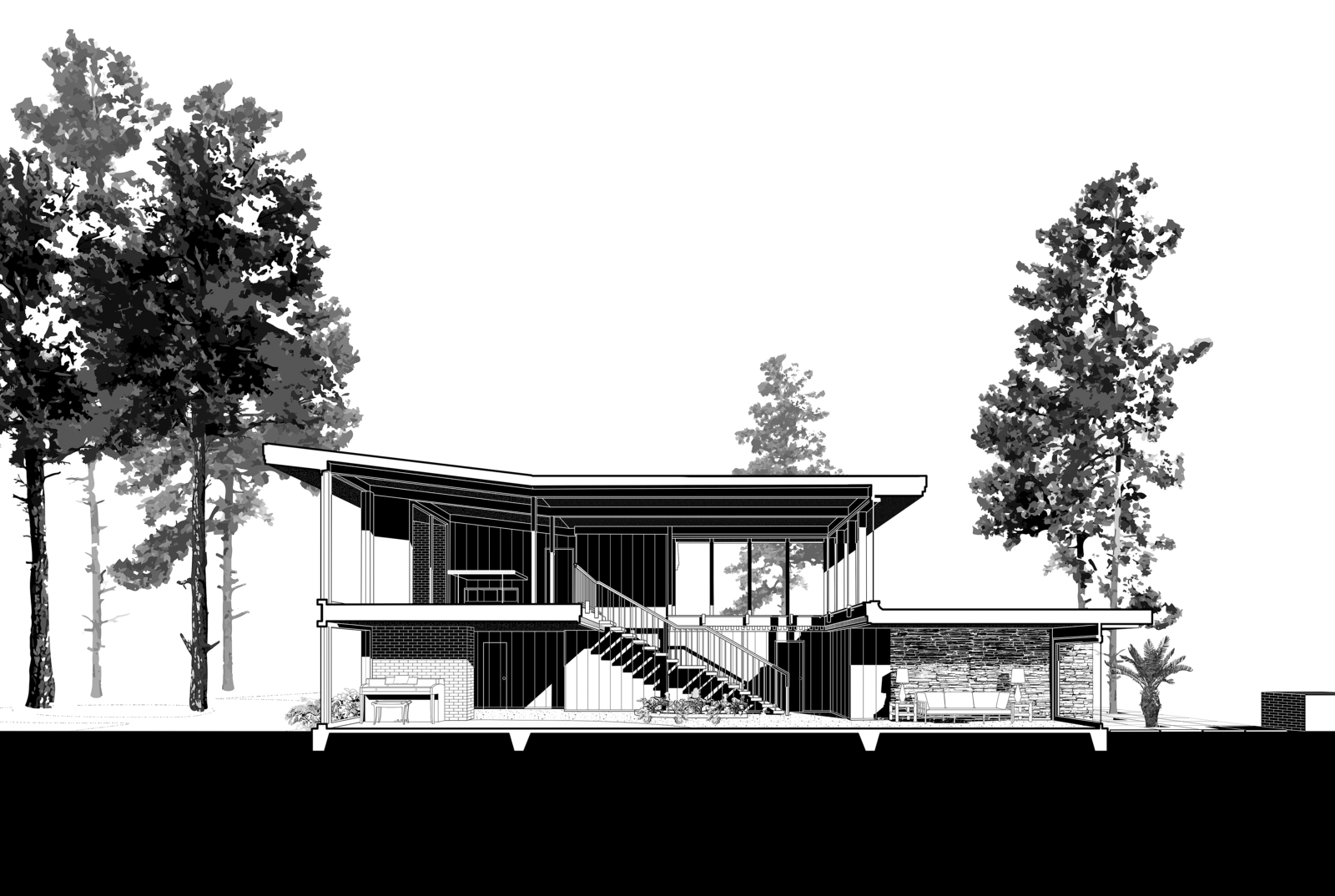

Though Chase designed many homes, his own was the most important. Completed in 1959, the Chase family opened their house to everyone from political heavyweights like Sen. Lloyd Bentsen and Rep. Barbara Jordan to heavyweight boxing champions Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. It became a place for political receptions, star-studded parties, and a forum for the exchange of ideas.

A model of the potential U.S. embassy in Tunis, Tunisia, designed by John Chase’s firm in 1992. Though Chase designed many local buildings out of his offices in Houston, Dallas, and Austin, he also had an office in Washington, D.C., and designed buildings at Washington Technical Institute and the national headquarters for the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

A rendering of the John Chase residence as seen through the courtyard. That detail was integral to the house, as an idiosyncratic design element, a place of solitude for the family, and as a gathering spot for parties and political gatherings. It wasn’t originally popular with Drucie, however. “At one point she burst into tears because she didn’t get how this open atrium was going to work,” Dudley says. “In many ways it became the heart of the home.”

Chase and his two sons, Anthony (left) and John Jr. (right), in front of the Chase residence in Houston. Family was incredibly important to Chase, and the home served as both an office and his primary residence. “This is John and the two boys out in front of the house that he designed for the family, and the first incarnation of it, because in 1968 they made that fantastic second story addition,” Dudley says. “I love it. Tony’s not wearing any shoes, and you can see in the window in the glass on the right side of the door, Ms. Drucie, her reflection there.”

Copies of John S. Chase—The Chase Residence, published by UT Press in 2020. Written by historian and Rice architecture professor Stephen Fox and UT architecture professor David Heymann, the book tells the story of the John Chase residence, a modernist home highlighted by an open-air interior courtyard with its own koi pond.

A rendering of the John Chase residence after an addition in the late 1960s added a bedroom, bathroom, and game room, and doubled the height of the courtyard, to which a staircase was added. Chase also built a home office upstairs, but the family man preferred to spend his working time outside of it. “John Chase had his studio space, but ultimately would end up drawing in the family space, the family room of the house,” Dudley says. “He had an office, but it seemed like he didn’t really use it a whole lot.”

Chase at UT Commencement in 1985. He founded the Black Alumni Advisory Committee with the Texas Exes, and, in 1998, became the first Black president of the organization. “I think he understood being a role model for other Black alumni, particularly African-American students who were coming after him in the School of Architecture,” Dudley says. “Overall, there was definitely a sense of pride in having graduated from the university, and having been able to maintain a relationship, which is wonderful.”

Watch our Alcalde Doc on John Chase.

Credits: Illustration by Ricardo Martinez Ortega, Photo Research by Matt Wright-Steel, Courtesy Briscoe Center for American History (3), Drawing by David Heymann, Brooke Burnside, Sarah Spielman, and Wei Zhou (2), Courtesy of Hester + Hardway, Courtesy of the Chase Family (2), Courtesy UT Press