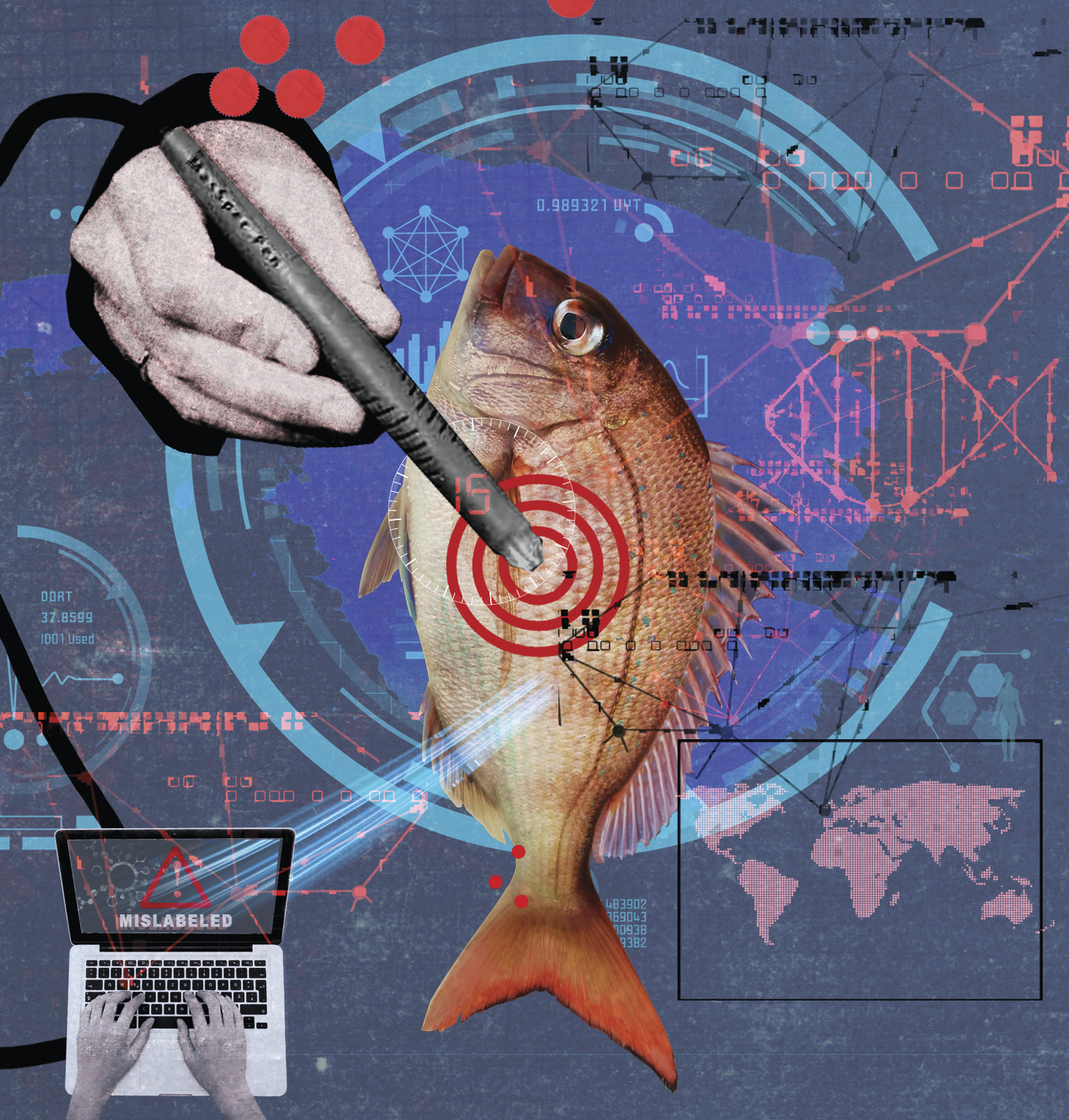

UT Researchers are Repurposing Cancer Diagnosis Technology to Battle Fish Fraud

Each year, Americans consume nearly 10 billion pounds of seafood, almost all of it imported. But what lands on a boat in the South China Sea is often very different from what ends up on your plate when you order seafood in a restaurant or purchase a fillet in the grocery store. Recent research in the peer reviewed journal Biological Conservation suggests that around 8 percent of global seafood products are mislabeled, but for some choice species, like snapper, that number can be as high as 87 percent.

Fish fraud is a rampant problem in the seafood industry that has major health, environmental, and economic consequences. Mislabeled fish are often imported from environmentally destructive fish farms or illegally caught in protected waters, which makes it challenging to implement sustainable fishing practices. And if the fish in the package is not what it seems to be, there is a chance it can cause illness by exposing people to industrial contaminants, allergens, or toxins like mercury or ciguatera, which causes a long-lasting form of food poisoning. But even if the mislabeled fish is safe to eat and sustainably caught, consumers are still being defrauded by paying high prices for inferior products.

Today, the government Food Safety and Inspection Service inspects less than 1 percent of all seafood imported to the United States to ensure that it is properly labeled. This is largely due to the time it takes to verify that seafood is the same as what it says on the package and makes it difficult to enforce bans on fraudulent fish. Earlier this year, Abby Gatmaitan, a UT chemistry graduate student, found an unlikely solution to this seafood scourge in a breakthrough technology developed by UT researchers for an entirely different application: rapidly diagnosing cancerous tissues.

In 2017, a team of researchers led by then-UT assistant professor of chemistry Livia Eberlin released the MasSpec Pen, a handheld device that can detect the presence of cancer in the human body by simply touching the tissue. Eberlin and her team developed the MasSpec for use during surgery to determine if all cancerous tissue had been removed.

“There’s a lot of clinical data that shows removing all the cancer during the first surgery gives the patient the highest chance of survival,” Eberlin says. “But it’s really tricky for surgeons to know if they’ve removed it all, so we wanted to make the incredible performance of mass spectrometry available to them to identify tissues.”

The MasSpec pen is about the size of a Sharpie marker and is wired to a mass spectrometer, an instrument that analyzes a material’s chemical fingerprint. When it touches human tissue, it releases a non-toxic fluid for 15 seconds and then sucks the fluid into the mass spectrometer for analysis. Based on the chemicals it sees in the fluid, researchers can tell if cancer cells are present.

“It’s a simple interface, but remarkably powerful,” Eberlin says. “I still get blown away by the depth of molecular information we get.”

When Gatmaitan joined Eberlin’s lab in 2016, her background in forensic applications of molecular chemistry led her to explore other uses for the MasSpec Pen, like detecting fraudulent fish. “Tissue is tissue, whether it’s in surgery or in meat,” Gatmaitan says.

Earlier this year, Gatmaitan published her research in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Using samples of fish she bought from a grocery store, she demonstrated how the MasSpec pen could correctly identify each of the five species of fish she tested. Moreover, the device correctly identified the species about 720 times faster than the leading alternative meat evaluation: a DNA testing method called polymerase chain reaction.

“Most verification of meat is visual,” Gatmaitan says. “But once you have that fillet of fish, you can’t really be sure what it is just by inspecting it visually. There is some DNA testing that gets done, but it is very expensive and can take a lot of time.”

In the future, Gatmaitan hopes to expand the pen’s capabilities to determine the species of fish and where it came from. She says fish bred in a fishery or caught in a certain region should show distinctive chemical fingerprints that make it possible to determine their provenance.

Gaitman says the pen might also be useful for detecting fraudulent practices in other meats as well. She has already tested the MasSpec pen on beef, for example, and was able to successfully differentiate meat from grass-fed and grain-fed cows.

Eberlin says government agencies have already expressed interest in using the MasSpec pen to detect mislabeled fish. Compared to the arduous regulatory process required to use the tool in a clinic to detect cancer, she is optimistic that it can be quickly deployed to reduce the amount of illicit seafood imported into the U.S.

“Clinical diagnostics is a very exciting application, but it’s a hard path to implementation,” Eberlin says. “So, it’s exciting that we may actually implement it for some of these other uses before we have a product that can be used by medical professionals.”

Credit: Sarah Hanson