The Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum Celebrates 50th Anniversary

Editor's Note: As of Aug. 9, 2021, The LBJ Presidential Library is closed. The National Archives and Records Administration is temporarily closing the LBJ Library due to an increase in COVID-19 cases in Travis County, Texas.

Lyndon B. Johnson oversaw a tumultuous time in American politics, culture, and society. It was an era of unrest, new ideas, and emerging distrust in institutions. In many ways, we still hear those echoes today. The memory of that era reaches a new milestone this year, as 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of one of UT Austin’s crown jewels: the LBJ Library. The alabaster hilltop icon remains a popular part of the campus, even with its temporary closure to the public, and its caretakers are looking ahead to new ways to connect the record of the nation’s past to its citizens in the present.

It may be taken as a given today that the records of a presidential administration are the property of the American people. But that hasn’t always been the case. Like many rare and illuminating historical objects—art and artifacts, for example—the letters, memos, and other tangible records of a presidency have fetched handsome prices from well-heeled collectors looking for surefire investments. In the 1990s, letters penned by George Washington fetched prices up to $500,000. When Richard Nixon, famed recordkeeper—and record-destroyer—resigned the presidency in 1974, his family even attempted to charge the federal government to recover his files.

Nixon’s immediate predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, took a different approach. Shaggy-headed and sporting horn-rimmed spectacles in retirement, Johnson arrived in Austin in May 1971 for the ribbon-cutting of his own presidential library, archive, and museum. In the five decades since, the facility has continued to expand its role. What began as a repository of records has since become an engaging museum that includes a permanent civil rights exhibition and even a moving, life-sized animatronic LBJ. Johnson, a president who courted his own share of controversy, wanted his library to be an honest and full record of his time in office.

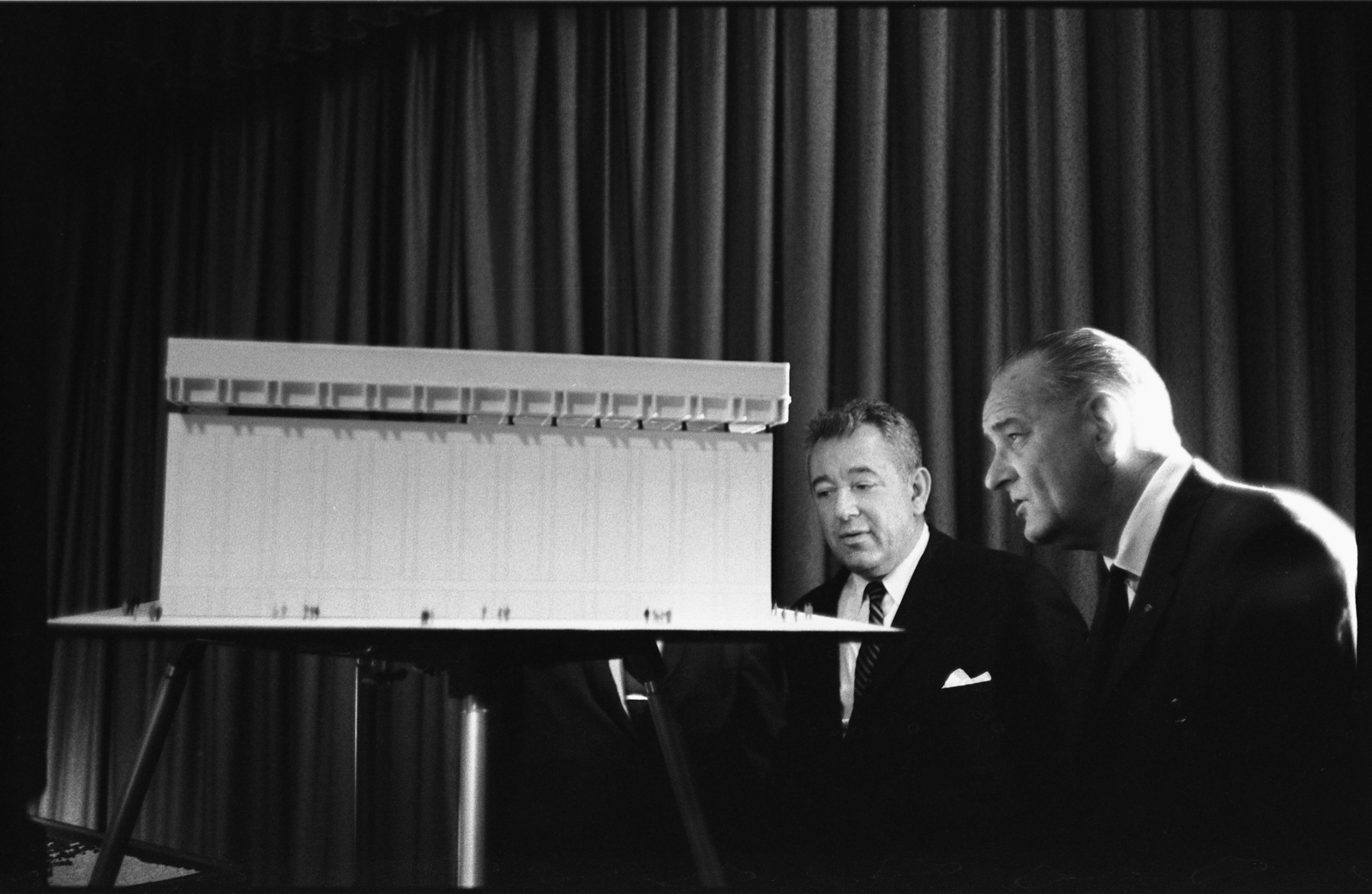

UT donated the land for the site in 1965, and by 1967, after a series of meetings between the Johnsons and architect Gordon Bunshaft, the massive construction project began, culminating in the iconic, megalithic library and the adjoining Sid Richardson Hall, home to the LBJ School of Public Affairs. Since its opening to the public, complete with protests and ceremonies (and the scale replica of Johnson’s Oval Office, which remains essentially untouched), it’s seen several changes and renovations, right alongside historical and popular analysis of its namesake.

Director Mark Atwood Lawrence says the library functions as a “core aspect of a democratic system,” keeping the nation informed on presidential precedent. He joined the library just eight weeks before COVID-19 forced a nationwide lockdown.

The year and a half closure provided a new impetus for the LBJ team to find novel ways to share the president’s story. “We want to make our assets more available,” Lawrence says. “COVID-19 has accelerated the process to get the information out to people who are far away from Austin.” A new virtual exhibit, for example, shares recordings from Johnson’s presidency—another marked difference from his predecessor, Nixon, who fought to keep his presidential records out of the national system, a fight that led all the way to the Supreme Court. “I think of presidential libraries, and certainly the LBJ Library, first and foremost as a repository of presidential resources,” Lawrence says. That function attracts more than researchers, however, as the public often wishes to learn more about earlier eras. In the case of Johnson’s tenure in the Oval Office, it’s an era that cast long shadows from the 1960s to today. Lawrence’s team is dedicated not only to complying with the law and function of the archives for government and for scholars, but sharing that history with UT students, visitors, and the general public.

Over the years, the institution has expanded its reach, hosting workshops and webinars for educators, and developing new projects, like a new website developed in collaboration with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, which shares nearly 800 hours of recorded phone conversations from Johnson that had been ordered sealed for 50 years. In the coming months, they’re looking to premiere a new exhibit dedicated to the life and times of the ever-popular First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, the namesake of UT’s Wildflower Center. “As I think about the next 50 years,” Lawrence says, “I think the challenge for me, and for others in the period to come, is to keep doing what we do really well: archives, public programs and outreach.” Or as LBJ himself put it, to observe the history with the bark off.

Credit: Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Library

An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to LBJ Library director Mark Atwood Lawrence as Mark Atwood.