New Blanton Exhibit Showcases Prominent but Underrecognized Figure of the Second Harlem Renaissance

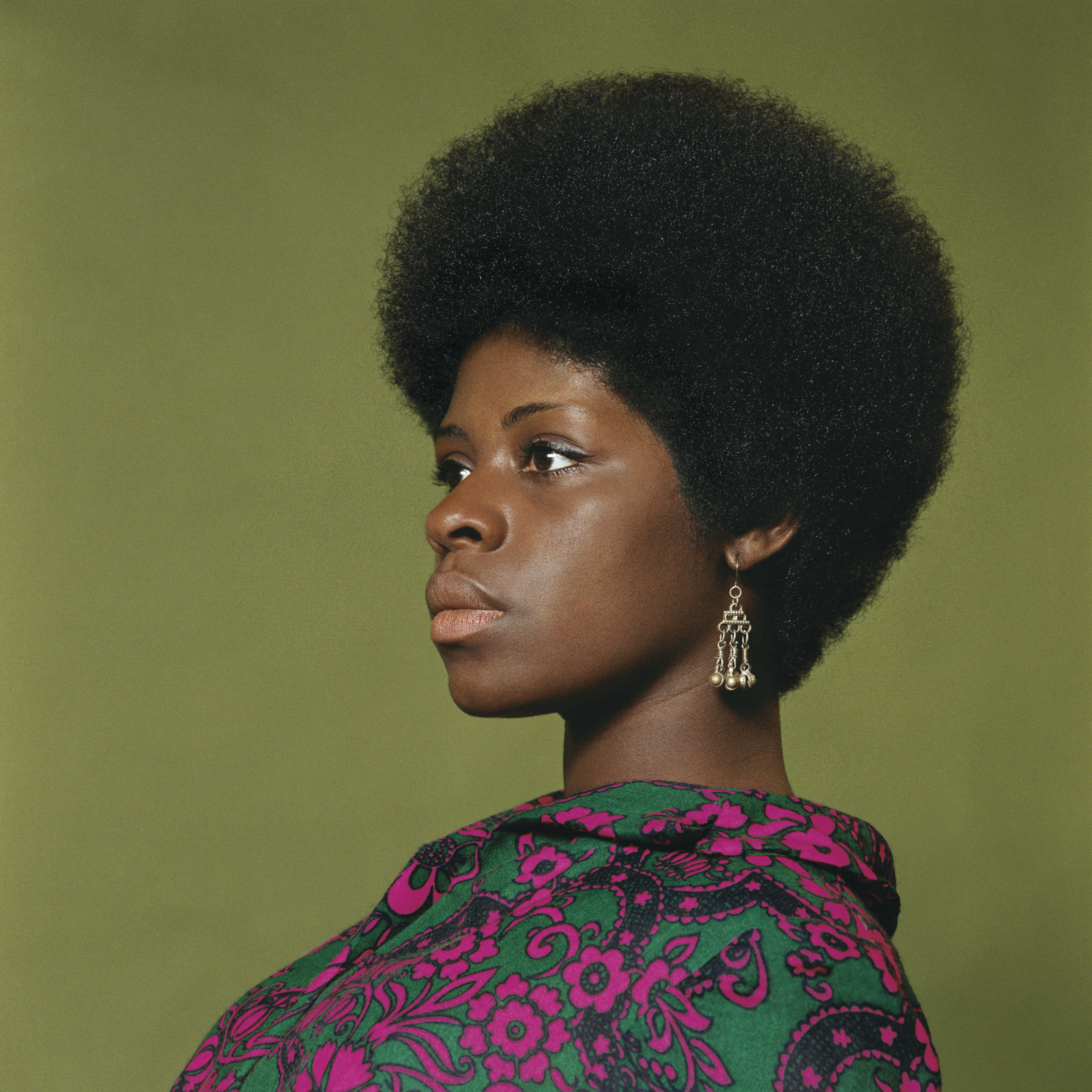

“‘Black Is Beautiful’ was my directive,” writes photographer Kwame Brathwaite, in the monograph that accompanies his upcoming exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art. “I focused my craft so that I could use my gift to inspire thought, relay ideas and tell stories of our struggle, our work, our liberation.”

Now, in the first-ever exhibition dedicated to his expansive career, Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, introduces visitors to the man who helped champion that phrase as a rallying cry for a broad embrace of Black culture and identity. Opening June 27 and running through September 19, 2021, the exhibition showcases the work and life of Brathwaite and his prominent role in the second Harlem Renaissance.

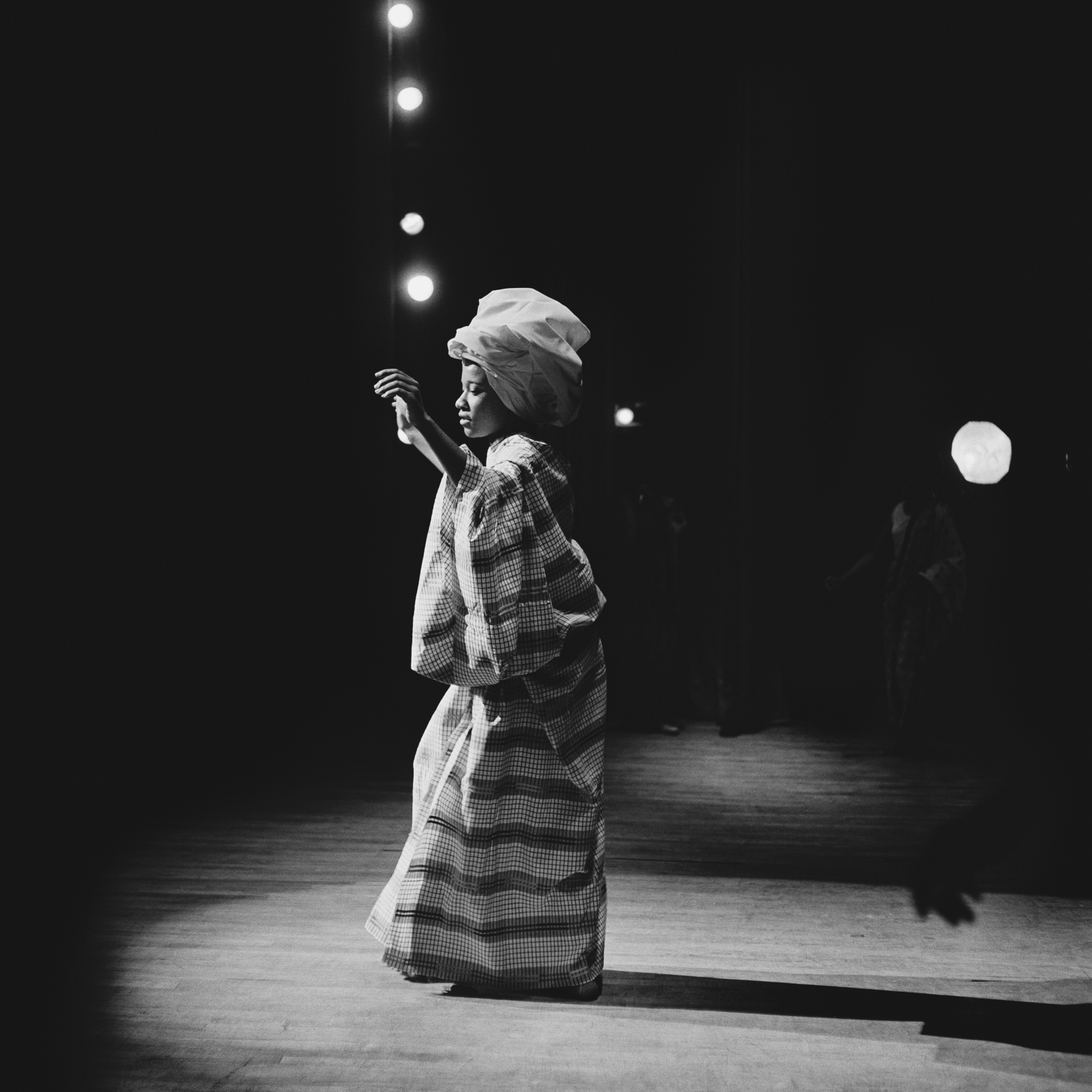

In addition to more than 40 vibrant photographs, the exhibition features original album covers, jewelry, and three mannequins dressed in full outfits from fashion shows staged at the modeling agency Brathwaite helped found, Grandassa Models. “It’s such a great time capsule for the 60s … the visual delights of those colors and patterns of that era, the behind-the-scenes of jazz clubs, there’s one level where you can go and enjoy all of that,” says the Blanton’s Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Claire Howard, who organized Black is Beautiful for the museum. But that’s not what excites Howard, MA ’12, PhD ’20, the most.

“On this other level, it is so historically rich, in that his ideas connect to so many different things,” she says. There’s the idea of community and placemaking, which continues to be especially timely in a place like Austin, Howard says, “where we’re looking at huge gentrification.” Then there’s the idea of alternative visions of beauty—Brathwaite worked to counteract the notion that there’s only one way to be beautiful. “And then there are other threads running through,” Howard says, “like buying Black, that we continue to see as really crucial to empowerment within communities.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1938, Brathwaite found himself working in the intersection of activism and art early on. As a teenager, Brathwaite and his brother, Elombe Brath, along with friends from high school, founded the African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS). A collective of politically engaged artists, the group organized jazz concerts in Harlem and the Bronx, and it was at those concerts that Brathwaite got his start as a photographer.

Black is Beautiful is full of iconic, intimate moments Brathwaite expertly captured of Harlem’s late 1950s and 1960s jazz scene. There’s an image of singer Abbey Lincoln belting out a note in an expression of such fervor that you can almost hear the music drifting out of the photograph. In another, taken at a performance at the Randall’s Island Jazz Festival in New York City, the lighting, expressions, and eyes all shine so brightly on Miles Davis that his star power feels magnetic, transcending the image. Wall texts adapted from author and historian Tanisha C. Ford’s catalogue essay provide context for Brathwaite’s images throughout the exhibition. “Music is the lifeblood of Brathwaite’s photography,” she wrote in a 2017 piece in Aperture, “Jazz set the rhythm for all of his work.”

His talent at both capturing—and styling—a moment for maximum beauty comes across in his striking fashion portraits of the Grandassa models, too. “He realized that representation shapes perception in a lot of ways,” Howard says, “and that by showing these high fashion images of women who didn’t look like your typical models, that would shape a certain understanding from outside the community.”

Brathwaite obsessively preserved his photo negatives, and within his activist circle, was known as the “Keeper of the Images.” But his images—especially those in this exhibition—have rarely made it into art galleries, if at all. It’s an under-recognition that was due to a combination of factors, Howard says, including racism against Black photographers, bias against photography as fine art until recently, and his celebrity and musical images being more broadly appealing—and financially sustaining—than his more artistic work. His son, Kwame S. Brathwaite Jr., and gallerist Philip Martin, MFA ’00, have been sifting through those diligently preserved negatives, printing pieces that hadn’t been before, exposing his more artistic images. And they have found a receptive audience amid today’s social climate that is shedding light on racial inequity.

“There’s so much history that must be made known, so much to share,” Brathwaite writes in his monograph. “My goal has always been to pass that legacy on and make sure that for generations to come, everyone who sees my work knows the greatness of our people.”

Credits: Kwame Brathwaite (8), courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles