New UT Research Could Help Turn Inhospitable Soil into Fertile Ground

Around May of last year, after a few months of working (and doing just about everything else) from home, I decided to turn my concrete balcony into something a little more lush. Like anyone who has been confined to a very small condo during the pandemic, I became a bit obsessive over something that, pre-COVID, I had never even considered: creating a personal oasis out of an uninspired slab.

I spent lunch breaks wandering around outdoor garden centers and evenings scrolling through Central Texas gardening blogs. I bought star jasmine, carefully twining and training it along the metal railing as it grew. I filled the corners with tall potted cacti that drew blood from my arms as I wrestled them out of their nursery pots. And I coaxed bushy green hibiscus plants to flower, which delighted me with bright pops of red and yellow. With no way to sustain the weight of raised beds, late-night Googling led me to discover hydroponics. Now, most evenings, I walk through my carefully landscaped flora and fauna to harvest everything from cilantro to bok choy to strawberries from a three-tiered vertical gardening tower.

Watching my urban jungle come alive has been sort of astonishing—to see growth, possibilities, and nourishment bursting from an overhang I’d once written off as too small and lifeless. It has certainly been a powerful daily reminder of my blessings, and it was, I’ll admit, something that made me feel generally smug. Until I met Guihua Yu, an associate professor of materials science in UT’s Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering and Texas Materials Institute.

While I’ve been puttering around my balcony, Yu has been busy running experiments that put my COVID victory garden to shame. Near the intersection of Dean Keeton and San Jacinto atop the roof of the Cockrell School’s Engineering Teaching Center building, radishes, planted in a new type of soil created by Yu and his team, are thriving with almost no watering at all.

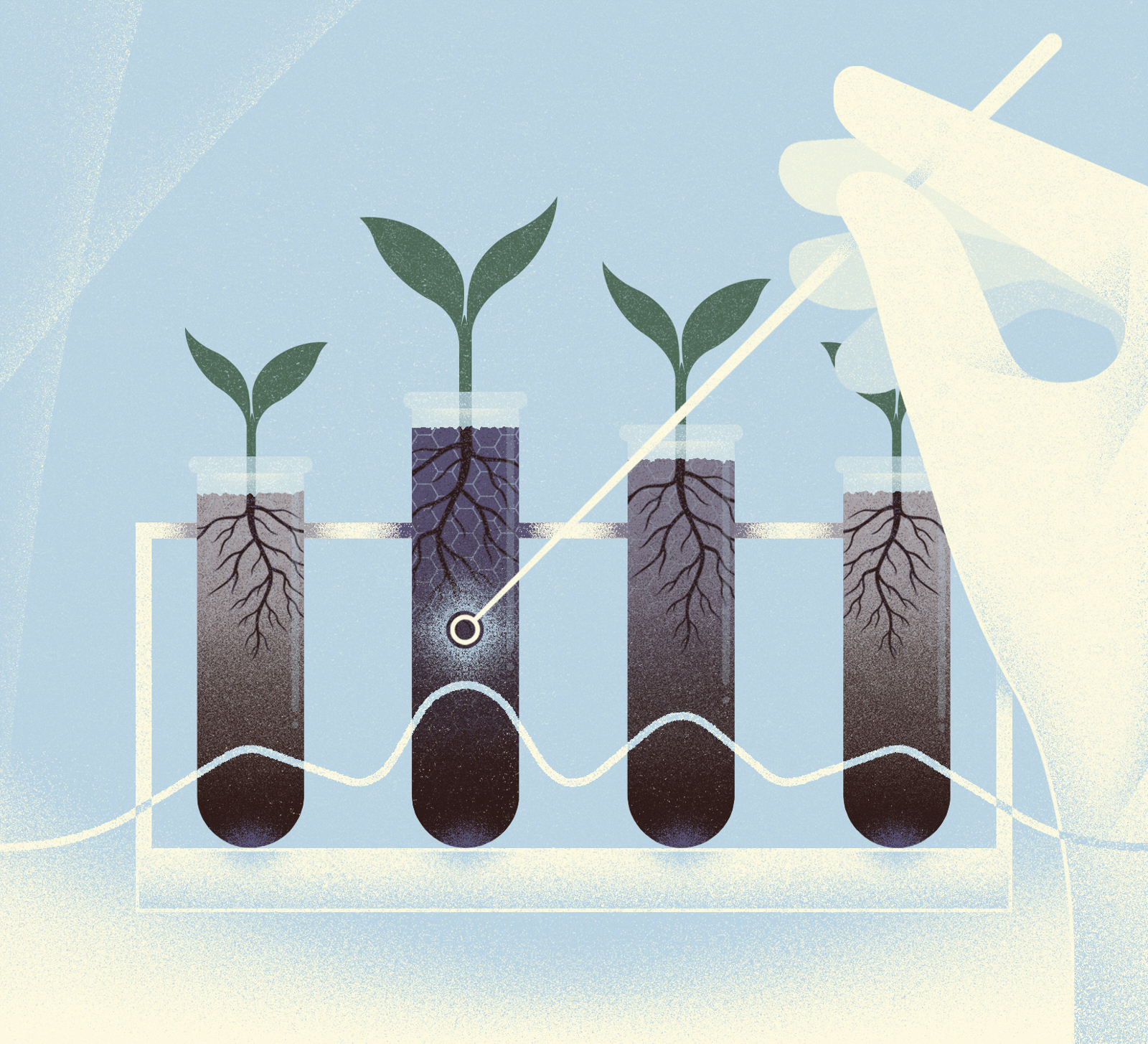

Since Yu came to the Forty Acres eight years ago, his work has focused on developing hydrogels materials—similar to ones used in the biological field for drug delivery—to make an impact on energy and sustainable technologies. More specifically: The researchers are interested in pulling water from air, or, “atmospheric water harvesting.” In 2019, Yu and his team published a breakthrough solution for access to safe drinking water in the journal Advanced Materials. They wrote about hydrogels, designed to be like “super sponges” that can absorb and retain large amounts of moisture (i.e. water) from the air, and return it as clean and usable water.

Now Yu and his team are applying that same technology to create self-watering soil. At night, when the air is cooler and more humid, the hydrogels placed in the soil pull water out of the air. During the day, as the sun warms the soil, the gels are activated and release their water into the soil for the plants. A bonus: As the water is released, some goes back into the air, which increases local humidity and makes the entire cycle run smoother.

As climate change brings increased droughts across the globe, the technology has the potential to reduce water use in agriculture. But it goes beyond that—the gels have shown promise in converting what we think of as totally inhospitable soil, like sand, into something farmable. In one experiment, Yu and his team planted radishes in the sort of sandy, parched soil you might expect to encounter in August in the West Texas desert. In some of that soil, they mixed in their gels. After two weeks, the radishes grown in the hydrogel soil had survived without any irrigation—except for one initial round of watering. Meanwhile, despite being irrigated several times during the first few days of the experiment, none of the radishes in the gel-less soil survived more than two days.

“Once we mixed our gels with the sand, it became kind of a soil—one that can get water efficiently and begin to grow some of these very basic kinds of crops,” Yu says. To him, that means there’s an opportunity to grow crops in extreme conditions. It’s a need he says that may only increase, as more areas that were once fertile farmland become inhospitable during periods of prolonged droughts. “If these gels can be made extremely low-cost,” Yu says, “they can actually alleviate this global desertification and help maintain a wider area. Areas that have become agriculturally irrelevant can be useful again.”

My balcony was never exactly a desert, but it certainly wasn’t useful, either. Now, I am feeding myself from it daily. I haven’t bought a plastic clamshell of lettuce (and subsequently let it wilt and go to waste in my fridge) for six months. The impact of this kind of sustainability, of course, is minuscule—and is a privilege only afforded to those with the resources of time, space, and money. But when I talk with Yu, I can’t help but see a common thread: When we push past our impulse to write-off a space, or a soil, and let ourselves dream a little, we may be able to transform it for the greater good.

Illustration by Andrius Banelis