A Texas Law Graduate's Quest to Uncover the Story of the State's First Black Attorney

A few years ago, I found myself at the Texas Supreme Court building looking for information about the first Black attorney in Texas history. As I toiled away in the building’s basement archives, poring over the latest in a seemingly never-ending series of dusty record books, I thought about how my quixotic quest had started more than two years before.

The Texas Bar Journal had published a feature called “We Were First,” which told the stories of the state’s legal pioneers: the first Asian-American judge, the first woman admitted to the bar, and so on. A member of the Journal’s editorial board, I was chagrined that as a group, we couldn’t agree who was Texas’ first Black attorney. As a longtime Texas resident and attorney, and a 1989 law graduate from The University of Texas—where the Heman Sweatt case paved the way for desegregation across public education in America—answering the question was important to me.

And so I began a years-long research project that would take me from the archives of the State Bar in Austin to courthouses in counties like Fort Bend and Matagorda, where I dug through contemporary newspapers that marveled at the story of the man they then referred to as “the colored attorney.”

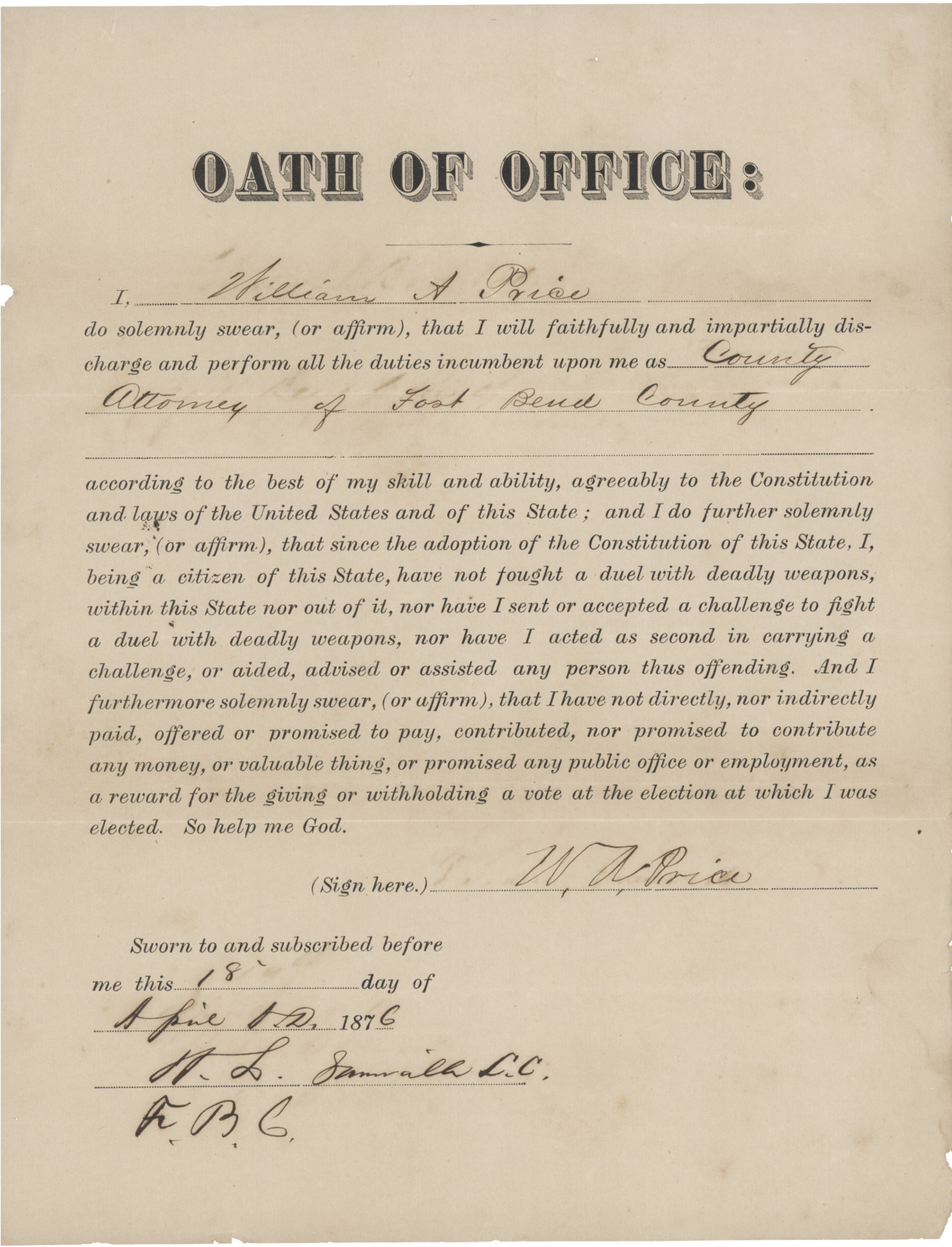

Despite some historians erroneously listing Allen Wilder, one of Texas’ first Black legislators, as its first Black attorney, the evidence I was uncovering pointed to an even earlier legal mind named William A. Price. As I continued to read, Price began to appear to me as more than just Texas’ first Black lawyer—he also seemed to be its first Black judge and elected county attorney. And when official local records historically listing “all” elected officials curiously omitted this first Black man elected in Texas to serve as a county attorney, some digging in the rare documents of local historical societies and museums provided the “eureka” moment I needed—voting records and a signed Oath of Office—to complete my search. That moment came while digging through records at the Fort Bend Museum.

In September 1950, Sweatt, Virgil Lott, George Washington Jr., Jacob Carruthers, Elwin Jarmon, and Dudley Redd became the first Black students to enroll at The University of Texas School of Law, buoyed by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision earlier that year integrating the state’s flagship law school in Sweatt v. Painter. Although Sweatt would ultimately withdraw from law school due to health issues (Carruthers, Jarmon, and Redd also did not complete their course of studies), Lott went on to graduate in 1953, becoming UT Law’s first Black graduate and the namesake of one of the Law School’s most prestigious honors, the Virgil C. Lott Medal.

Lott was followed by Washington, Ollice Maloy Jr., and Gloria K. Bradford (Texas Law’s first Black female graduate), who all graduated in 1954 with LLB degrees. All went on to distinguished legal careers marked by even more firsts. Lott became the first Black judge in Austin; Washington became Dallas County’s first Black assistant district attorney; Maloy was appointed as Tarrant County’s first Black assistant D.A.; and Bradford was the first Black woman to try a case in Harris County District Court.

They all helped pave the way for the more than 70 Black undergraduates—known as the Precursors—who enrolled at UT in 1956, two years after another milestone Supreme Court opinion: 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education.

Yet all of these trailblazers, from Sweatt onward, and even the Brown v. Board decision itself, follow Price and his inspiring story of perseverance in Reconstruction-era Texas.

William Abram Price was born free in Alabama to parents of mixed Black and Native American ancestry. He studied at the country’s first private historically Black college, Wilberforce University, near Xenia, Ohio. After the Civil War, Price, like many, saw Texas as a land of opportunity for a multitude of reasons. There was a lot of cheap land that was available during Reconstruction: either because of plantations that were abandoned or lost by now-impoverished white landowners, able to be acquired through sharecropping, or given as part of the “40 acres and a mule” Freedmen’s Bureau guarantees.

Records show Price purchased land in Matagorda County and presumably began life as a farmer, but a chance encounter with the legal system soon changed the course of his life. Finding the minutes of the ensuing case among the Matagorda County court records would finally answer the question that had been hounding me.

In 1871, a dispute with another farmer over the alleged theft of an iron wheel for a cotton planter, Price defended himself so ably before the all-white jury that while he was found guilty, he was only assessed a fine of one dollar. The case was retried, and this time the guilty verdict came with the jury’s choosing: a punishment of five minutes in the county jail. After Price appealed, the district attorney dismissed the case.

Price’s own defense did not go unnoticed, and in 1872, he served as a justice of the peace in Matagorda County. Price’s interest in and study of the law soon led to his successful application for admission to practice law in 1873, becoming the first Black lawyer in Texas.

Most applicants to the bar at the time lacked a formal legal education, having “read the law” under the tutelage of a local lawyer or judge, and been found qualified and “of good moral deportment” by a committee of local attorneys. Despite the lax regulations, Price’s ascendance was remarkable.

Price had a meteoric rise, and in 1876 was elected county attorney (equivalent to a district attorney today) for Fort Bend County. After seeing historians misidentify Texas’ first Black lawyer and seeing “official” local histories that whitewashed the past—to the point of listing a white man who didn’t serve as the Fort Bend County Attorney during the years of Price’s tenure—I got chills when I found the historical documents illuminating Price’s achievements.

In addition to his acceptance by the legal community, local residents seemed to hold him in the highest regard. I found accounts about Price in newspapers that describe him as being universally well-regarded and respected.

His talents went beyond the law; he is credited in one article with coming up with a canal or levee solution to a chronically overflowing river that had plagued the county. An article in the May 14, 1874, issue of the Galveston Daily News mentions Price, “the colored lawyer of this place,” as the mastermind of the canal, and that “the good feeling existing here between the two races is due to his influence; the white people speak very highly of him.”

However, with the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, many of the gains made by newly enfranchised Black Texans were lost, and Price fared no better. He resigned his office of county attorney in 1877 and joined the Exodusters movement, which was founding all-Black communities in a more tolerant Kansas. There, Price helped start the state’s first Black-owned law firm, and he and his partners litigated some of Kansas’ earliest civil rights cases.

Price’s crowning achievement would come in 1891, with the Kansas Supreme Court’s decision in Knox v. Board of Education of Independence. Eight year-old Bertha Knox and 10-year-old Lilly Knox, both Black, had been denied the right to attend a school only 130 yards from their home by Kansas’ school segregation law, which had been upheld by the state’s Supreme Court just a year before. Price argued that the local boards of education in cities like Independence didn’t have the right to exclude the Knox girls “for no other reason than that they are colored children.” The Kansas Supreme Court agreed, and for the next half century, Kansas became the venue for the constitutional question of public schools and segregation. By 1954, the NAACP and lawyers like Thurgood Marshall would build upon precedents like the Knox case in successfully arguing to the U.S. Supreme Court that another pair of sisters, Linda and Cheryl Brown, shouldn’t have to bypass a closer elementary school reserved for white students and travel farther away to an inherently unequal all-Black school. In this way, while they lived in different times and there is no direct evidence that Sweatt knew of Price’s achievements, the two are inextricably linked in the fight for civil rights and access to education.

My path of researching Texas’ first Black lawyer led to a previously overlooked connection to this civil rights milestone and, indirectly, to The University of Texas’ own complicated history on this topic. Sweatt and his fellow trailblazers stood on the shoulders of Price—a man whose legacy is measured not in monuments but in the countless Black Americans who followed him into the legal profession.