This Longhorn Wants to Land the First Private Craft on the Moon

Born three years before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, Sharad Bhaskaran spent his youth poring over Star Trek reruns and devouring sci-fi novels.

“It was just the idea of exploring the unknown, a general fascination with the topic of sci-fi, and the idea of exploration,” Bhaskaran says. “That was pretty cool.” Since that momentous July day in 1969, only China and Russia have joined the United States as countries that have landed spacecraft on the moon. Most recently, in January 2019, China made history by landing a rover on the far side of the lunar surface.

But 2021 is shaping up as the year that, for the first time, a private craft—not one launched by a government—will land on the moon. And a Longhorn might just be the one to get one there first.

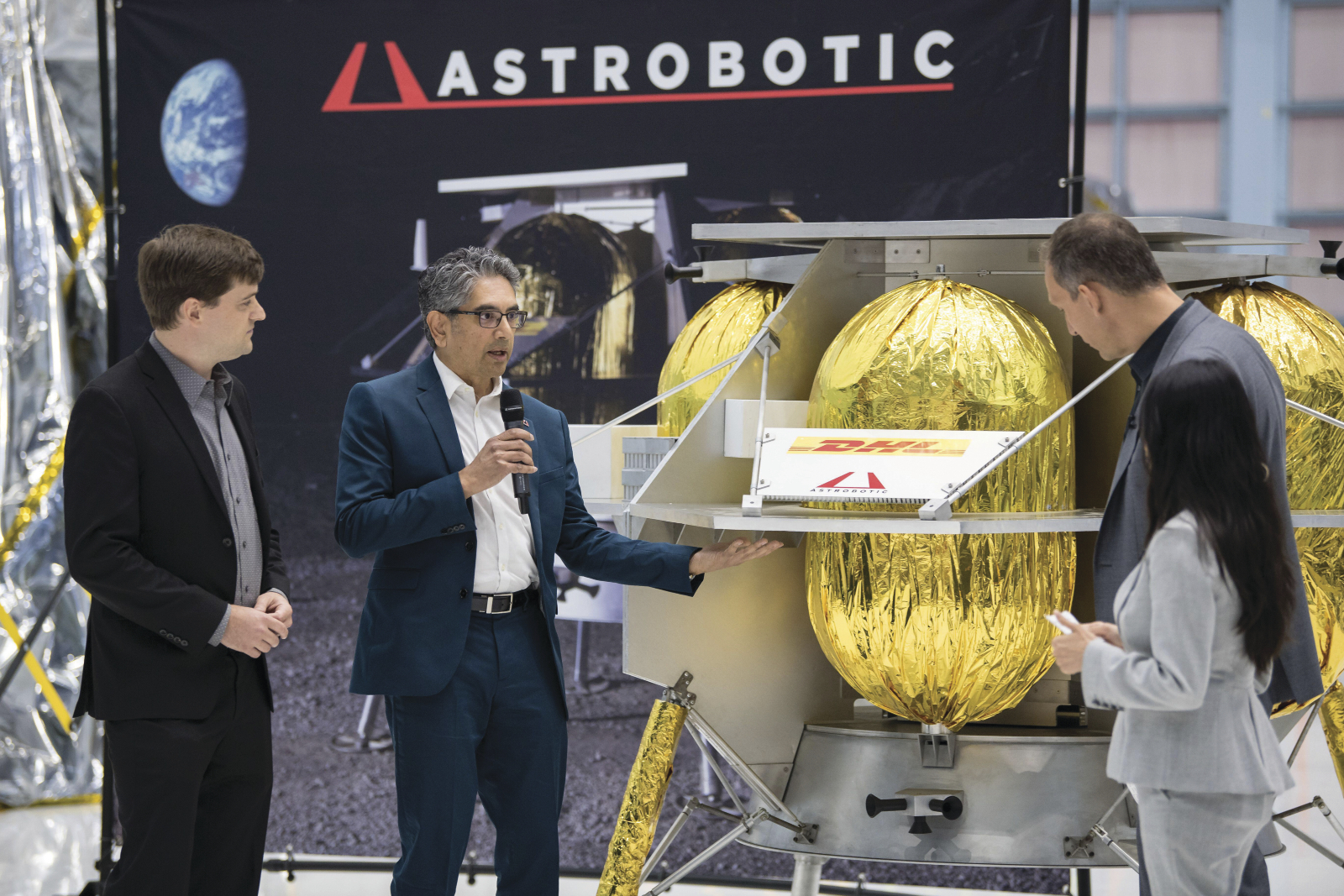

Bhaskaran, BS ’89, is now the mission director for Astrobotic Technology, a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based space robotics company. Astrobotic is in a tight race with other companies like Japan’s ispace and the Houston-based Intuitive Machines.

In short, if Astrobotic succeeds with its lunar landing, Bhaskaran will have helped chart a path to where no commercially-funded robotic spacecraft has gone before. And, if Bhaskaran has it his way, gone to stay.

“What we’re trying to enable is a lot of science experiments with small payloads that could better understand and characterize the moon’s environment, much of which is needed to then set the stage for future human landings on the moon,” the mechanical engineer says. A spacecraft’s payload is its human or cargo capacity.

Bhaskaran says that the early studies, using Astrobotic’s lander and landers of their scale, could lead to a better understanding of what it will take to sustain human habitation on the moon for extended periods of time.

“It’s a stepping stone to establishing a permanent human colony on another planetary body,” Bhaskaran says. And it’s not idle daydreaming.

“I see a human community on the moon, I see a human community in space. I believe in Star Trek,” says space lawyer Michelle Hanlon, co-founder and president of For All Moonkind, which works to create an international agreement to preserve human artifacts in space. “I think the realm of space has so much to explore and, you know, we are a species that has exploration in our DNA from the beginning of time.”

Despite growing up in College Station, Bhaskaran always had his sights set on The University of Texas for its mechanical engineering program.

In October 1989, just months after graduating from UT, Bhaskaran landed a job as a structures engineer for what would become Lockheed Martin, which contracted with NASA’s Johnson Space Center. He would spend the next 25 years on various space-related projects.

His work included leading more than 30

U.S. payloads onto Russia’s former Mir Space Station, which spent 15 years in orbit. Bhaskaran also supported the International Space Station Human Research Facility in various leadership roles and led numerous projects as program manager.

Bhaskaran left Lockheed Martin in 2014 to become an independent consultant before joining Astrobotic in 2016. Looking back on his now-30-year career in the aerospace industry, he pinpoints his senior year at UT as the moment where it all clicked.

“I didn’t really have any clear plan, but in my final year [at Texas] I was thinking some kind of job in aerospace would be the most fun. I certainly didn’t envision that I would ever be mission director for a major program like this.”

Bhaskaran says a catalyst for putting Astrobotic on the verge of landing on the moon occurred in 2007 when Google offered the Google Lunar X Prize, a $20 million reward for a company that could put a robotic spacecraft on the moon by March 31, 2018. Nobody won. But the contest helped launch companies like Astrobotic, which was originally spun out of Carnegie Mellon University by William “Red” Whittaker, a professor at the school’s Robotics Institute and the company’s chairman.

Eventually, Astrobotic won a partnership with NASA, giving it access to NASA’s expertise and technology, and plans moved forward for Astrobotic’s lunar lander, Peregrine. It will deliver payloads to the moon for companies, governments, universities, nonprofits and individuals, including multiple payloads worth nearly $80 million from NASA. These include scientific and technological experiments. One will measure hydration, carbon dioxide, and methane—resources that could potentially be mined from the moon—while also mapping surface temperature and changes at the landing site.

Individuals can buy a MoonBox that Astrobotic will take to the moon carrying a memento such as a family photo, a ring, or a cufflink. The mementos “will be stored on the moon for centuries to come,” the company says. The price ranges from $460 to $1,660, depending on the size of the box.

Bhaskaran says delivering payloads is what drives the company’s efforts and what drives him. Thirty years after discovering his passion at UT, he realizes the stakes of what he’s

now doing.

“If that’s not successful, we’re not successful,” he says.

Illustration by Irina Kruglova; photograph via 2020 Images/Alamy Stock Photo