Our 2020 Outstanding Young Texas Exes on How They Got Here—and What’s Next

These four Longhorns have achieved big success before even turning 40. Initiated in 1979, the Outstanding Young Texas Ex Award recognizes Texas Exes age 39 and younger who have made significant achievements in their careers and service to the university.

Gerardo A. Interiano, BA ’03, JD ’06, Life Member

Born in El Salvador, Gerarado A. Interiano moved to Texas when he was 8 years old. As the VP of government relations at Aurora, a company building self-driving technology, he leads their efforts to engage with governments to help define policy for the burgeoning industry. Before that, he worked at Google, where he helped launch the Google Self-Driving Car and Google Fiber, and Waymo in the southwest U.S. He has also held senior roles with U.S. Congressman Lamar Smith, Texas Gov. Rick Perry, and Texas Speaker of the House Joe Straus.

On giving yourself the space—and grace—to figure it out:

I started at UT as an engineering undergrad, realized I was not cut out to be an engineer, and quickly ended up studying economics. The trickier part was deciding what I wanted to do afterward. Career Services was really helpful—I did one of their tests, and one of the options on there was law school. That was the first time I had given some serious thought to going to law school. We all have this perception that we have to understand exactly what we’re going to do when we get to college, and that we can’t change our major. When, in reality, part of what we’re supposed to be doing in college is figuring this out.

On navigating that pressure post-college:

Long after you graduate, you’re still asking yourself those questions. You’re still trying to figure out: What’s next? What does my career look like? What do I want to do, what do I want to be? My advice is, look 10 years down the road. Don’t focus on what you’re doing right now, because those questions are still going to be there. Try to understand what impact you want to have when you’re 40 and 50 and 60. Work backward from there, knowing that there are multiple paths to take. And that it’s OK if you have different experiences along the way, because ultimately those will make you better at what you do.

On how to work backward:

In law school, I had a mentor who told me, “Write a letter to yourself when you’re 50 years old and tell yourself, what is it that you’ve achieved over the last 25 years?” Talk about everything: your family; nonprofits that you’re involved with; your community, work, your faith, your professional life—think about everything and study people who are at that point and figure out how they got there. Different people got there in different ways, but there’s no need for you to reinvent the wheel.

On finding what drives you:

I work for a company where our entire mission is about improving people’s lives. If we succeed as a company, our roads will be safer. Lives will be saved. On top of the fact that we care about how we engage in our communities and about the work that we do, I think it’s even more important that our mission is to improve people’s lives. And that is really exciting—to know that I work for a company that’s going to literally revolutionize transportation is something that is incredibly motivating and inspirational.

On taking risks:

One thing students I speak with tend to ask me the most is, “What would you have done differently back in college?” My answer has been the same for years: I would have taken more risks. Me taking a risk now, as a married father of three, is very different than the risks that I could and should have taken when I was younger. Now I have to take more calculated risks. And that’s not to say I can’t take risks, but the value proposition changes quite a bit. So, when I talk to college students, what I encourage them to do is take more risks. This is the time to take all the risks and not look back. Go do the things that you may not be able to do later in life. Go explore and try different things; try a different career, because it’s only going to get harder to take risks the older that you get.

On work-life balance:

I remember somebody telling me that equilibrium in science is really, really hard. There’s this mentality when we talk about work-life balance—that it has to be a balance. And the reality is that it’s close to impossible. And so, the way I think about it is when I am with my family, I’m going to do everything possible to be as present as I can in the same way I do when I’m at work. That doesn’t mean I’m going to be able to do it 50-50 every time. I don’t think there has to be a perfect balance between work and life. I remember seeing a friend of mine who put the fact that they were a father and a husband on their LinkedIn profile. And I put it on mine because it’s a constant reminder of what’s important to me.

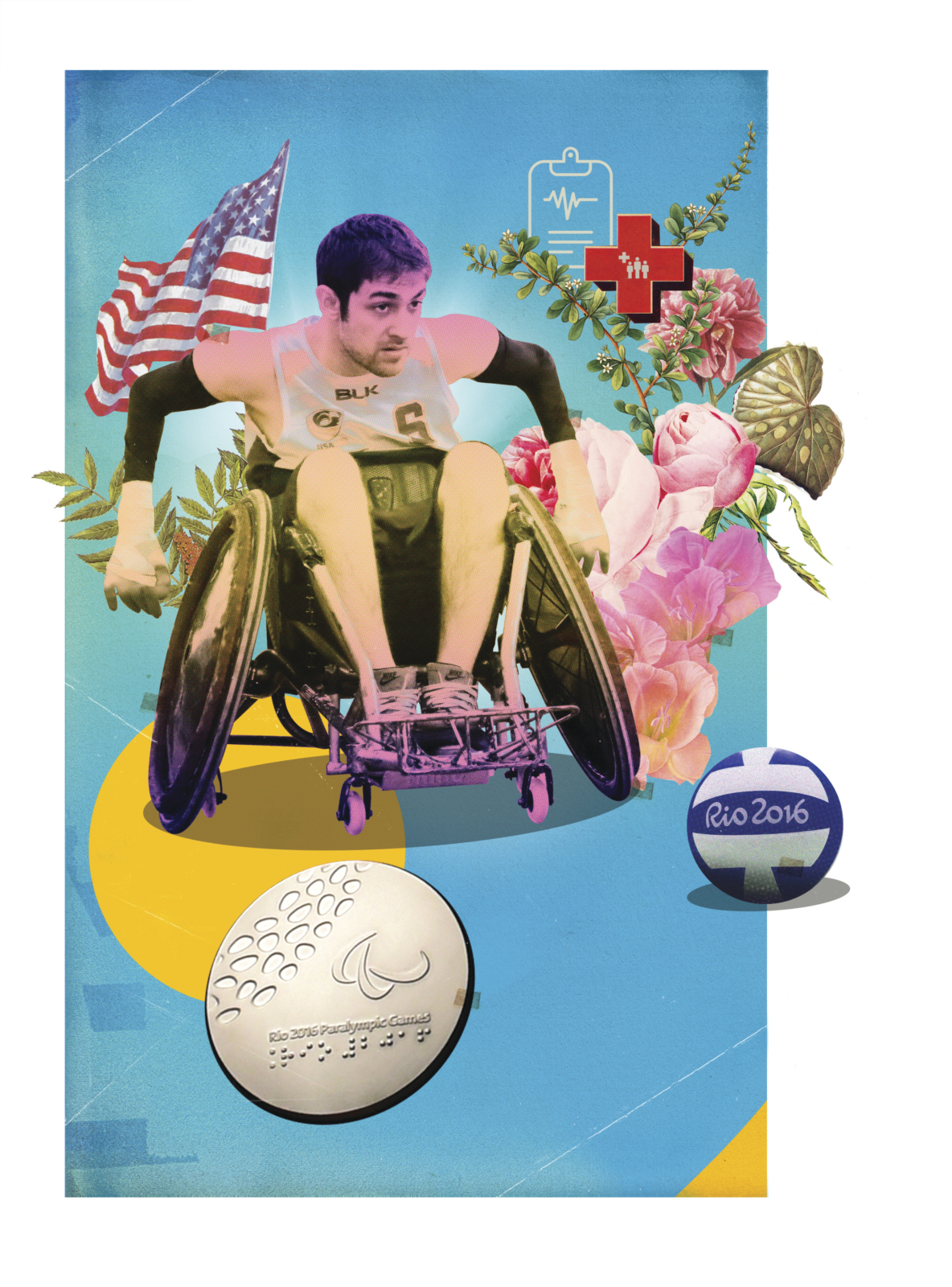

Jeff Butler, BBA ’14, Life Member

Paralympic silver medalist and entrepreneur Jeff Butler founded his first company, VIPatient Telehealth, in 2015. He represented Team USA at the 2016 Rio Paralympic Games and won a silver medal in wheelchair rugby. He has been training for the upcoming Tokyo Paralympics since. Following the rescheduled Tokyo games, he’ll attend the Stanford Graduate School of Business to pursue an MBA.

On setting goals:

When I was 13, I broke my neck in a car accident, and a couple of years later, I found wheelchair rugby and I totally fell in love with it. So, I started consuming as much wheelchair rugby as I possibly could. I was going to tournaments close to home, clinics all across the country, and just any place I could play rugby. Along the way, I met people who had been on the Paralympic team before, and I was totally enamored by their skills on the court and their confidence in life. I wanted to be like them. In the conversations I had with them, they were like: “You know there’s nothing stopping you.” So I set trying to make the Paralympic team as a goal.

On achieving your dreams:

It wasn’t until after I graduated in 2015 that I made my first actual Team USA. I was in the clouds for six months; it was the greatest feeling in the world, and even more so because I had tried out five times prior and gotten cut. It was my last hurrah. I was ready to be on the team or concentrate on my professional career. I think a lot of what I can attribute that to is a good support system around me: fantastic teammates to help me learn … my coach, who really helped me understand where I needed to develop. And then just making micro-goals. At tryouts, it’s like, “Hey, I’m going to do these three things this much better at this set, because I know I messed up last set,” and just really taking this highly iterative approach in my own playing style, and in my growth as a player and individual.

On finding opportunity:

When I was in the hospital, my uncle visited me and said, “You can’t see it now, but this is going to open so many doors for you.” I was lying there, couldn’t move anything, like, “What?” But it’s so true. When you are facing adversity, that’s when you have the most opportunity for growth and opportunity. And I think that’s the mindset that is going to help people get through [COVID-19]. Adversity pushes you outside of your comfort zone so abruptly and immediately that you’re forced to grow and change. And if you’re well-positioned to take advantage of that opportunity, it will be just that.

On pushing past difficulty:

People have a tendency, myself included, to get so involved and focused on challenges that are immediately in front of their face. Being able to zoom out to 30,000 feet and look at how this affects your whole life, instead of what’s happening right now, is really useful. When you’re faced with increasing small levels of adversity, you’re leveling up in life. Most people don’t have something as shocking as breaking their neck, but everyone goes through adversity—and you can lean on an experience that you’ve had in the past, or remind yourself that what’s going on now will give you an experience in the future that you will be able to lean on. It’s a subtle mindset shift, but it’s important and useful.

On finding symmetry:

In business school, you do thousands of group projects. And there’s been a lot of overlap between skills that I’ve learned in business and skills that I’ve learned in athletics. One of the most important things that I learned at McCombs was interpersonal dynamics and understanding how the things you say affect other people. I was able to transfer those skills into my athletic career. And the same could be said in the other direction: playing a team sport, growing up, and understanding what good leadership looks like, and understanding what kind of things motivate people. There’s an interplay between business and athletics that happens that you wouldn’t initially think about.

On how technology can be more inclusive to people with disabilities:

I’m not generally one to say we need more business regulation—I’m a business major. [Laughs.] It’s difficult because the government exists and public goods exist where there is a need, but it’s not a profitable need. The disability population largely isn’t a highly profitable market to attack. And I’m not sure what it takes. I can’t imagine that people with disabilities in leadership positions would hurt—I think it would help—but I still think you would struggle to make a compelling profit-loss argument. I think that’s where we need help from the public sphere to say, “Hey, we understand that no one wants to do this, but it’s a cost of doing business.” What’s really neat is that the question you asked is so difficult to answer, but there’s going to be an answer to it. And I’d love to be the person who sits down with a group of other really smart people and helps figure out the answer.

Leticia Nogueira, PhD ’10

As senior principal scientist at the American Cancer Society’s Data Science Department, Leticia Nogueira investigates health disparities in cancer care that can be addressed by policy changes. She has made significant contributions evaluating the effects of the Affordable Care Act on cancer care, and how climate change impacts cancer patients. She also manages the National Cancer Database at the American Cancer Society.

On embracing change:

When I first joined UT, I was focusing on plant genetics, and ended up having the opportunity to switch mentors halfway through my PhD. I was lucky to have the support of the graduate school to be able to do so. I was working with animal models at the time and after presenting the results at a conference, decided that I wanted to do something more population- based. Animal models are really important—there’s so much that we know about biology and cancer that comes from animal models, but it takes a long time for it to be implemented. And I’m just not that patient. [Laughs.] So after I finished my PhD, I actually enrolled into a master’s of public health program, which is backward—usually people do the master’s first. Through it all, my career really took a different turn and moved upward.

On finding your passion:

Coming here from Brazil, the obesity epidemic in the U.S. was mind-blowing to me. Now, of course, the obesity rates in Brazil are just as high, but back then it was a startling difference, and looking at how obesity and cancer were related really hit home for me. Whenever I read the literature, whenever I was designing the projects, there was so much more that was relatable with cancer and obesity to me than genetics and plant genetics were. Every time I read about it, I could think about the implications on people’s lives and how we might be able to change it and make people’s lives better. I asked the graduate school if I could switch my focus halfway through, and they were very honest. They told me, “It’s going to be a lot more work, you’re going to have a lot to catch up on because you’re going to have to leave your projects behind and start brand new ones. But if that’s where your heart is, that’s where your interest is, we support you.” It was terrifying, because it’s 2 1/2 years that you put into your projects that you just hand to somebody else and start from scratch. There was not a whole lot of sleep for a while, but it was so worth it. And every time I went to work, I had that passion that was coming with me.

On the intersection of science and policy:

When I started work with obesity and cancer, I thought, very naively, that if you give people all the information, you make the right choices, right? Well, no. That’s not how we work. [Laughs.] I learned that the hard way, as I was doing more research and publishing more, and some of it got media attention, and then—nothing. You can tell people that smoking causes cancer, and you still see the number of smokers. Once I started realizing this was not so much about personal choices, what is it about? What makes people be healthier? And it was very obvious that policies can have a high impact on how people behave. Which is really important to me—I don’t just want to generate knowledge. I needed to be making an impact.

On how her work shifted as her thinking evolved:

It wasn’t even like, “Well, why are you smoking?” It’s not like there’s a character flaw in that person. It’s maybe that a person who is stressed out, living in a neighborhood where they only have access to a convenience store, is bombarded with advertisements for smoking. The price of the cigarettes are sometimes cheaper than a healthy meal, and it will make them feel better for longer. If you have more policies that will allow people to have access to healthy foods, and higher taxes on smoking, that can influence people’s behavior. When you started looking at these studies that implemented a different policy in one place and then compared it to a place where it didn’t happen, it was amazing. You started really seeing changes. There was an aha moment for me, like, I shouldn’t be trying to make each person change their behavior because they know what’s good and bad for them. But if they are in a situation that makes it easier for them to make healthy choices, that helps. So that’s what I started doing more and more research about health disparities that are amenable to change through policy, because I really believe that’s where we can make the biggest change.

Melanie Weber, BS ’04

In 2019, a UT press release trumpeted the news that Melanie Weber had become the first woman and the first Hispanic person in the history of human spaceflight to lead a Launch Pad Team on the day of launch. She leads Crew and Cargo Accommodations for Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft and was recently granted a U.S. patent for innovative seats that provide Starliner crew safety and comfort.

On following your heart:

When I was in second grade, I’d go to the library, check out books about animals, or Earth, volcanoes, earthquakes, atmospheric sciences, oceans … things like that. And then in eighth grade we took a trip to Johnson Space Center. And that was the first time I had been exposed to the history of human space flight. And I was so enamored with everything that I saw. All my classmates were playing the games, and taking pictures, and doing the fun stuff, but I was there going through all the memorabilia, going through the timelines of all the missions, and what we had accomplished and just taking it all in. And I knew pretty early on. I remember coming home right after the trip and saying, “Mom, I know what I want to do.”

On overcoming culture shock:

College did not come easily to me. I struggled. I was not like my husband ... everything just came so easy to him. I was the opposite—I had to study, I had to take time to do homework. I had to go to office hours, or study sessions, or meet up with other classmates so that I could get through homework and tests. And I was also going through culture shock. I was used to growing up in Corpus [Christi, Texas] where the population is pretty much half Hispanic, half white. And I was kind of thrown into this other city, this other culture, and I struggled a little bit with that. But I did join the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, which helped me connect with other Hispanics that were interested in engineering. And they helped build this small family for me. I was able to talk to students that were like me that I could confide in and work with, and adapt better and quicker.

On being a first:

It’s not something I ever planned. I’ll be honest, I was not aware that I was going to be the first woman or the first Hispanic to do that until a few months prior to me doing it. It was pointed out to me by somebody else at NASA. I was a little bit surprised because we had had so many shuttle launches that I assumed that would have happened already. The person who brought it up from NASA, he was the one to go back and investigate and go ask former pad leads if there had been a woman, and they were able to answer pretty quickly “no.” And then if there had been a Hispanic, and they also said “no.”

On imposter syndrome:

I understand how important this role is. We are the last people who will see the astronauts before they launch. We are the last people who touch the spacecraft, so we have to be perfect. And there were days where I would question whether I’m still the right person to do this. There were times where I wondered if they would come up to me and say, “You’re not qualified to do this role.” There were definitely times where I had to stand back and say, “You can do this. You know all of this in your head, you wrote this down, you designed the system this way.” Part of it is admitting that you do not know everything, and you will never know everything. However, you know enough to make sure that the job is done right.

On being a servant leader:

By nature, I’m a very passionate person. I think that passion really drives what I do on a daily basis. I do this because I love human space- flight, and I believe in it, and I want to contribute to make sure that it is successful. When it comes to my leadership style, I do sacrifice quite a bit personally for the good of the program. And I don’t know if that’s a good quality or a bad one. I think I’m still trying to understand and figure that out. But I just have to remind myself that what we do is important, and it’s important that we get it right. And how I fit into that puzzle—you know, the work that I do matters.

On handling stress:

I try to bring a lot of laughter daily. That’s ultimately probably what I do the most: joke with my coworkers. I love making them laugh. They love to make me laugh. And some people would probably be like, “Hey, do you guys work?” “Yes, we’re working, but this is also our stress management of how we work.” We just have to let loose sometimes and just have a little fun.

On regrets:

Life is really a journey, and sometimes you may not get to your goal right away. Sometimes you’re meant to deviate from your path. And it’s because you’re supposed to learn something new, either something new about yourself, or something that helps you personally, or professionally, before you’re meant to go to where you’re supposed to be. And that kind of happened to me. I always was fascinated of course, with space flight, but right before I graduated was when [the fatal 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia incident] happened. And I knew that I would not be able to work at least for the shuttle program at that time. And so it was meant for me to go work on something else for years and to know a bit about myself, to grow professionally, to learn things technically, so that I was prepared for my next jobs. A lot of people asked me, is there anything that you would have changed? And I always answer, “Absolutely not,” because I was meant to go through all of those experiences. And no matter how small something seems at the moment, it could contribute greatly to your future. You know, even when it comes to something like when me and my now-husband decided to pursue more than being friends—I could be in a completely different place right now, on a different program, in a different city. There’s so much that could have changed with any deviation of any decision I’ve made in my past. You can always go back, and go, “That one day, that I decided to go to that one meeting may have put me on my entire path.” And it’s crazy to think that sometimes things like that happen.

Illustrations by Matthew Billington