An Oral History of the Texas Blazers

In the spring of 1994, then-sophomores Paul Massingill and Robert Bleker were walking back to their dorms after a Student Leadership board meeting. It was a time when hazing was a major issue within UT’s Greek system and the pair felt that an alternative space for male bonding was needed. Just four years earlier, an intoxicated Beta Theta Pi member had fallen to his death from the roof of his fraternity house, and a Sigma Nu pledge was subjected to gruesome hazing in the basement of the legacy organization he’d hoped to join. After a high-profile investigation and court case, the latter fraternity’s chapter was suspended on campus. It was a reckoning for UT’s fraternity row, but the toxic culture hadn’t just disappeared. Massingill and Bleker started talking about what their ideal student organization would look like. The friends swore their group would not tolerate hazing of any kind.

It would be diverse in every sense. It would be wholly dedicated to service, the university, and the surrounding Austin community.

They were half-kidding at the time; it seemed far-fetched. But today, the 26-year-old service and leadership organization is one that incoming freshmen aspire to join, and one that added 12 new members in the fall via Zoom. The application and interview process to join Texas Blazers, the honorary service, leadership, and spirit organization, is thorough and rigorous. And as the group’s reputation has grown, it has become competitive. While no in-person meetings have been held for the past two semesters, current members foster a sense of community by sharing memes, joking about unusual Venmo requests, and serving by tutoring and mentoring over video chat. Through it all, they still define themselves as stand-up folks you can depend on, and set towering, high standards for themselves. This is the story of how the Blazers came to be, told through individual interviews with over a dozen founding through current members.

Interviews have been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Robert Bleker, ’00, Texas Blazers co-founder: [Paul] called me. “I’ve been thinking about our conversation. And I just wanted to ask if you were serious?” I said, “I was actually thinking about calling you. I am.” So I went to his dorm and we started putting stuff on paper, banging out ideas and that’s when the threefold purpose of the Texas Blazers came to life. We were kind of joking, saying, what would we call it? One of us said, “How about the Blazers?” It has connotations of trailblazing, but we could wear blazers like the Orange Jackets.

Paul Massingill, BA ’96, Texas Blazers co-founder: Robert and I started having individual conversations with guys we knew, and then we called a meeting on the Union patio.

Bleker: Paul and I were there, and we weren’t sure who was going to show up or if anyone was going to come, and a bunch of guys showed up who would ultimately make up the first 20 or so founding members of the Texas Blazers. We had a great conversation about the idea for the group. When we left, we all knew we wanted to start this organization. We always considered that to be the birth moment of the Texas Blazers.

Rich Reddick, BA ’95, Life Member, Texas Blazers founding member: Somebody said, “You need to talk to these guys.” I was a senior, but I was like, okay, these guys are the new generation coming up. Good for them. I had started thinking about my life beyond UT. I was ready to go and do something else. So I’d met them, casually. They had a meeting, and I was like, this is pretty cool, actually. I could see they were making an intentional effort to diversify a group from the beginning. A lot of groups start off being of a certain background, whether it’s Greek, or it’s people who are involved in Student Government. And then later on, they want to be more diverse. Well, you’ve kind of set that in motion already by the way you started the organization.

Eric Stratton, BA ’98, MS ’12, Life Member, Texas Blazers founding member: Being the treasurer of the College Republicans, I would go up and make my deposits at the Texas Union student bank, and I’d run into Rob Bleker. One day I walked in and he was like, “Would you be interested in coming to this meeting about putting together a new organization?” I was not one of the original members sitting around the table at the Union on Sept. 7, 1994. I was on the next layer out. I went to that next meeting and it just clicked.

Jeremy Pemble, BA ’94, Life Member, Texas Blazers founding member: Slowly but surely, the first recruiting class happened. We were looking for good students—good-natured, but also good academically. I often joke with my wife that I never really partied in college because I was always in a meeting. But I was not alone. The Blazers fell into that same class.

Massingill: They had to be at least sophomores, and they had to have at least a 3.0 GPA. These guys were already campus leaders. They were folks who were involved in all different kinds of organizations—orientation advisors, and we had several different colleges represented. So when we went public, that enabled Blazers to start up fairly quickly and get established right out of the gate.

Stratton: Each new class of Texas Blazers we recruited was required to develop and put on their own unique community service project. This project helped bring them together and mold their identity themselves, as a class. That, in turn, tied their identity to the organization, because they were doing something that was service oriented, hands-on, which tied back to the Blazers’ ultimate mission. You own it, and that right there was huge because it meant that they, in the process of doing that, became Blazers. What differentiated us is that our focus was—let’s be hands-on, let’s get in there and actually do.

Neal Makkar, BBA ’15, Life Member, 2014-15 Texas Blazers chairman: Nothing I’m about to say is against Greek life. But the reality is, for a lot of kids, you don’t have the funds to do it, because it’s expensive. They have their own philanthropies, but it’s a very different feel. Their community and brotherhood comes first. For us, service came first. And it was accessible. We had dues, around $170 a semester, and that covered food at meetings and the pins and ties that you had to get to be part of the board—operating costs.

Reddick: The thing we found with men’s organizations is that sometimes the service mission was secondary to the partying. There’s a strong correlation between Eagle Scouts and Blazers. It’s that kind of vibe. Guys who were committed to raising money or having the most volunteer hours, that’s who we ended up getting in the organization.

To understand the ethos behind the Blazers, one needs only turn their eyes to the Orange Jackets. Bleker, Massingill, and their cohort were friends with the Orange Jackets president at the time, Erica Bramer (then Blewer), and they wanted to emulate many aspects they admired about the historic women’s honorary service organization, which had been on campus for more than 70 years. Their focus would be on positive male role models and mentoring.

Erica Bramer, BBA, BA, ’95, Life Member, 1994 Orange Jackets president: To set out and found something—something with lasting power—is a pretty audacious goal. I was impressed they did it at all, and that they did it so well, and the fact that they modeled it after Orange Jackets, to some extent. They made a point of being proactive reaching out to us. I don’t think I would have ever felt like they were stepping on our toes, because they were filling a void. There wasn’t a male equivalent, in my assessment. There are other clubs that label themselves as service organizations, but it’s really all about the social cachet. So a club for men that was sincerely dedicated to service the way Orange Jackets was, was relatively unique.

Bleker: We talked to Erica about it. We were able to set up a couple of mixers with the Orange Jackets, and just say, we respect you, and it’s amazing what you do. We’re starting this organization, we’d like to work alongside you guys, if you would allow us. We were trying to be respectful of the history of the Orange Jackets, which is long and storied. We weren’t trying to take over anybody’s position on campus.

Bramer: It’s unusual to be the women’s organization and have a men’s organization modeled after you. It’s almost always the opposite. The fact that the guys had the maturity and confidence to copy the girls was really quite cool. There was sincerity behind that, and it wasn’t a passing reference, like, “Hey, will you guys do mixers with us, because it’ll be good for our recruiting?” It was, “How does it work? What is your structure? What are your requirements? How do you recruit?” This was not a social club masquerading as a service club. It was a service club, but you might make some good friends with like-minded values.

Bleker: We wanted an organization that was truly diverse, that had people from all walks of campus and different cultures, an organization where you felt welcomed no matter what your sexual orientation or race, or whether you’re an engineer or a liberal arts major.

Andrew Limmer, BS, BA ’08, MBA ’14, Life Member, 2006-07 Texas Blazers chairman: They aspired to be a group of individuals with high standards, doing good things, and that manifested in having a fairly diverse group. I’m a white male that grew up in a solidly middle class, mostly white suburb of Houston. Being in Blazers was a good formative experience, because it gave me a lot more understanding about people from other places, and gave me close relationships with people that I might not have otherwise crossed paths with.

Reddick: So many things at UT are traditions, they have been around for 50 years. This was brand new, so we could set in motion any traditions we wanted. And of course, I had no idea it was going to continue. It was nice to say, the things I don’t like about other organizations, we can change those from the beginning. You can ensure that we have a racially diverse group where there’s not going to be the situation of having one Black person, or one Latino, because we’re doing it from the very beginning.

Limmer: We had a lot of other minority groups represented here, but for whatever reason, at the time, we didn’t have a lot of African Americans in Blazers. What you would notice is that if you got a handful of people from a certain group, they would start telling their friends, and over time, different parts of the organization would draw in different people. So I knew that if we could get some people from the African-American community to join it would likely lead to more folks coming. But you had to be somewhat deliberate about it. And I think organizations appreciated it when we made the effort to come and recruit.

Bleker: I had racist attitudes that I wasn’t aware of, and thoughts and ways of communicating that were informed by a racist community. Having conversations with guys like Richard Reddick—God bless him and his patience with people like me—that opened my eyes to the fact that the way I’ve thought about this all my life is wrong; that it supports a racist narrative. Those conversations we had shaped who I am today. That’s what I wanted my college experience to be; I wanted it to be one where I got to interact and have conversations with people who weren’t like me, and who had different perspectives. We wanted that to be a part of what the organization did. We just socialized together, and we achieved that.

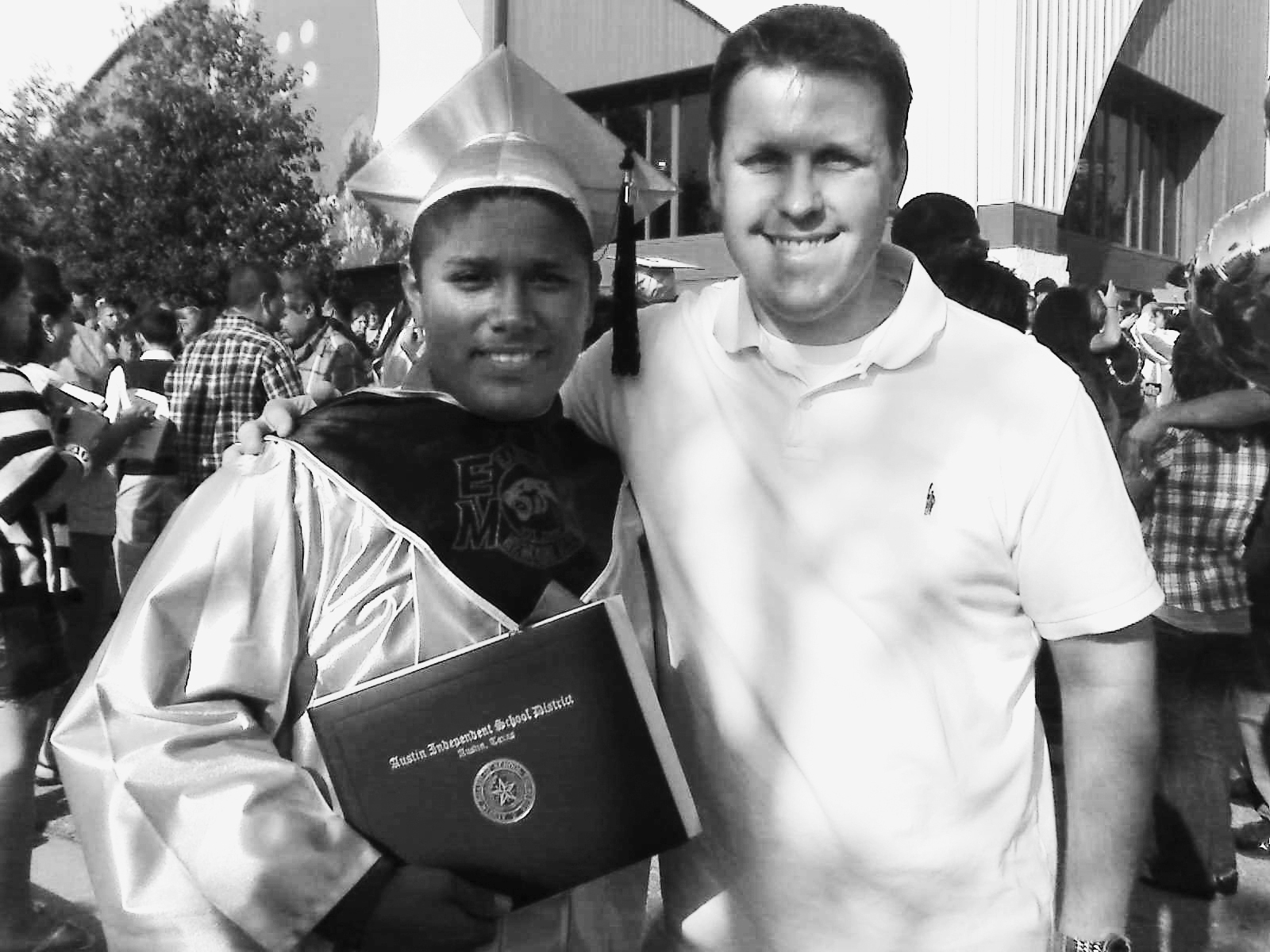

Reddick, who is now the associate dean for equity, community engagement, and outreach at the College of Education, set in motion a lasting relationship between the Blazers and the East Austin high school he’d attended, Eastside Memorial (formerly known as Johnston) in 1994. He and his high school classmates had been advanced, ambitious students, but the school was underfunded, and he noticed how the bars over the vending machines in his own cafeteria contrasted with the luxe dining hall at nearby Westlake.

The Blazers established a weekly mentoring and tutoring program at Eastside, offering career counseling and resume workshops, in addition to beautification projects like painting a mural, planting a community garden, and renovating the cafeteria. Supporting students at EMHS continues to this day.

Makkar: They call us their rock, because we’ve been there longer than any teacher or organization. So we tend to know more about the school than a lot of people there do. Sitting in a tutoring lab, helping a student when they were in need—those things were awesome, because you built a relationship with an individual student who sometimes you can track for several years.

Limmer: I worked with a freshman, doing one-on-one mentoring. He said one day, “I want to take this girl I like on a date. How do I get money?” I’m like, this is a great teaching experience, “Pick up some job applications.” So we brought them back to the school, we’re filling them out, and we got to the part about the social security number. He’s like, I don’t know what that is. So I said, “Go home and ask your parents.” He comes back the next week, and you can tell something was wrong. He’s like, “Mister, you’re not gonna want to be my mentor anymore. I didn’t want to tell you. I’m an illegal.” His parents brought him over when he was a young kid; he had no idea. I had a much more conservative view on immigration prior to meeting him. Now I have a more nuanced view about it. Having that experience humanized it for me in a way that I can understand the issue at a more complex level. Now with a lot of other issues, I resist the urge to take a hard stance, because I’m probably missing something.

Stratton: My mentee was a young Black gentleman; I was very fond of him. I got to take him off campus to go to lunch at McDonald’s. It wasn’t about helping him with his math homework, it was about sitting across the table from him over a Big Mac and just listening to him, and getting to know this young man and being able to pour into his life. He didn’t have a father figure. He didn’t have a good male example. So it wasn’t about the math homework; it was about the presence.

Many Greek organizations can trace their history back to the days of the university’s founding in the late 1800s. It’s daunting to look at all that history and start from scratch. But that’s what the Blazers did, and each year, as new members join the organization, and new alumni go out into the world, the history and traditions slowly build. The cross-generational bonds grow and deepen in the process.

Stratton: One of the first things we did as we were forming the board of directors was have a vice president of history and traditions. At our meetings, he would tell a story about something from the history of the university that was relevant to us today. Like, what’s the history of the Hook ’em Horns sign? How did we get Bevo? It was stuff like that to help pass the torch, help us be more familiar, especially if the roles we were going to play were ambassadors for the university.

Reddick: There could be a group of people excited about something, and when those people graduate or move on to something else, there’s no guarantee it’s going to continue. But we graduated the first year, and 10 years later, I came and gave a talk about the Blazers and Johnston. I was just like, holy crap, you guys are sharper than we were. You’ve got blazers, first of all. Back then it was like, go get a blue blazer and put it on. We didn’t have a uniform per se. I was impressed. It’s only gotten better. There’s definitely this cachet about the organization now that didn’t exist when we first started.

Limmer: Dean of Students Soncia Reagins-Lilly is sort of like a mom to the Blazers. She’s never had an “official” role as an advisor, but she became an advocate and supporter and has remained one to this day. She invited us to host an official university event, and afterwards, she was like, “all your pants are different colors. Your jackets don’t fit. You need to go get some nice, matching pants and jackets.” She still laughs about it today when we talk to her. We went to Men’s Wearhouse and everyone got measured. We ordered all the same khaki pants, and all the same shade of blue blazers, because Dean Lilly told us that uniformed blazers and pants would sharpen the organization’s presentation as university ambassadors.

Limmer: We started our first endowment when we were in school in 2006. We had been doing these fundraising events every year, and giving scholarships. At some point, we had $15,000, in this bank account run by a bunch of 19- and 20-year-old college students. And one of the chairmen before me, Matt Tabbert, put me on to this idea about setting up an endowment. So we mailed letters to all the alumni and did a little grassroots fundraising, and barely got it up to $25,000. It’s now grown to about $100,000, and goes specifically toward scholarships to UT for a student graduating from the East Austin area.

Billy Li, BBA, ’20, 2020-21 Texas Blazers fundraising chair: There’s a need to get students to UT, and that’s something that we’ve been trying to do for the past 25 years—encourage students to decide to go to UT. But now, we realize that there’s also a huge importance in trying to make sure that these students that come from schools, like Eastside, will stay here and have the education and the support and financial resources to stay here. People suffer from food insecurity and just not having the correct resources like professional clothing, or emergency funds.

Limmer: We went to Dean Lilly, and originally had the idea of a mentorship program and another scholarship, but she was like, these students are over-mentored. Sometimes these kids are just hungry, can’t afford to fix their laptop, can’t go buy a nice outfit for an interview, and it puts them at a competitive disadvantage. It makes it harder for them to squeak it out at UT. She’s like, “I have students come into my office that just need that little extra help so they don’t throw their hands up and withdraw.” I was pretty surprised. “Food insecurity,” she said, “is a huge problem.”

Li: So we created this new Texas Blazers Excellence Fund. And that basically is raising money to help the UT Outpost. They provide a free food pantry, a professional clothing closet, and emergency funds for students whenever needed. We felt that this was really important because we wanted to support the students here at UT. It’s just one step to get people here who might be first generation college students. It’s also about helping them have the resources to thrive here at UT.

Makkar: The Texas Blazers Excellence Fund has a goal of raising $425,000 in the next five years. We spent our first 25 years as an organization helping bring students to campus, and now the next 25 years, we’re going to dedicate to not only bringing them to campus, but helping them stay on campus and thrive while they’re here.

Stratton: I didn’t imagine that 26 years later, not only would the organization still be there, but it’s grown, it’s thrived. It has outlasted so many other groups. The fraternity I helped found is gone. But this is still here, and it still stands for the same principles; it still does the same things it’s always done. It’s lasting, and it’s still making a difference.

Willie Crawford III, Fall 2020 Texas Blazers Ember Class member: I was talking to a few other Black people who were Blazers, and they told me it seemed as though Blazers had a one Black person per semester quota, because there would never be any more than one Black person per semester in a new Ember [new member] class. But by the time I got there, obviously, that changed, right? Because the spring 2020 semester had like, three Black guys in it, and now there’s three in my class, and I’m hoping that in the future, there might be more.

The Blazers’ conversations around diversity have recently extended beyond race, toward issues of gender and identity. In June 2020, over several tense roundtable discussions conducted via Zoom, the Blazers officially made the decision to degender the language of the organization. No longer would they refer to themselves as “a great group of guys.” Brotherhood became community, New Guys (the former term for new recruits) became Embers, and Guys became Members, and Chairmen, simply Chairs.

Reddick: We started joking, saying “Brother Blazer,” because Robert and Paul were like, this is not going to be a fraternity. I came back to visit Blazers as an alum in 2007, and they signed their emails, YBB, “Your Blazer Brother,” and I’m like ... that was a joke. That actually became a thing?

Zafir Patel, 2020-21 Texas Blazers vice chair of alumni relations: To me, masculinity has always been about protecting those you care about, and doing everything you can for the people around you. It seems like that is what we stand for as an org. It perpetuated what I already believed, it strengthened my ideals, and made me feel more confident in feeling that way about my masculinity.

Reddick: There’s a conversation right now about gender-fluid and nonbinary students. Not to make it sound like it worked great and everybody was happy. I knew a student who was gender nonconforming who was a Blazer for a while, and it wasn’t a good experience for that student. But at least there were folks who were willing to lean in and have that conversation.

Limmer: The Blazers chairman came to an alumni meeting several years ago. He’s gay, and he was talking about different causes the Blazers were supporting out of the LGBTQ community. An alumni said, “I’ve got no issue with this, but Blazers is a service organization. We’re not a single issue advocacy group. So it almost seems like we’re going too far into this. We should support a lot of things, not just this one thing.” I was thinking, this alumnus is challenging this poor college student. What’s his reaction going to be? I was so impressed with how the student responded. He was respectful. He was like, “I completely hear you. I obviously don’t want people to think I’m pushing my own agenda as chairman. I can assure you, that’s not the case. But thanks for bringing that up.” And then the alumnus was like, “Well, I’m just bringing it up for consideration.” And they had a nice chat about it. Nobody got ugly.

Brett Dolotina, Spring 2019 Texas Blazers Ember Class member: In the spring of 2020, we had two new gender nonbinary members, so it resurfaced these conversations of what inclusion looks like. One of those conversations was about degendering the language.

Crawford: The more conversations I have, the more I am beginning to understand the reason behind degendering. As long as we continue to serve the community, and continue to share something, I think we’ll be fine.

Dolotina: As someone who is gender nonbinary, this was a basic decision to make the space more inclusive. I think, to a lot of people, this idea of being gender nonbinary meant, man-light, basically. It was holding on to tradition and holding on to what we know, in the face of multiple people telling you this negatively impacts them. It was dehumanizing, and it felt like my lived experiences of what I found to be negative parts of the organization were just met with these abstract thoughts.

Patel: I’m someone who clings to tradition. I have always seen value in not changing things. So initially I was on the side of amending our constitution to keep the old language, but also putting “slash Ember” or “slash Community” instead of just “brotherhood.” I ended up being shown the other perspective of—to our nonbinary members, that was still painful. And that’s something as someone who hasn’t really struggled with my identity in that way, I can’t ever truly relate to perfectly. But am I willing to keep a word that hurts others, one that doesn’t mean that much to me?

Bleker: What does it mean to be masculine in our society today? We had a sense that it didn’t mean a lack of strength. It meant being strong, but what is masculine strength? It’s looking out for your fellow person. It was listening and understanding other people’s perspectives, and being able to synthesize that into your own community. That’s the community we wanted to create. So I was happy to hear that they changed the wording from brotherhood to community because that’s more accurate and better reflects the original intent of the organization.

Li: Change is always met with some apprehension, because it’s easy to stay in tradition. But ultimately, the organization is full of people that really are empathetic. That’s something I truly admire about Blazers—everyone cares a lot about other people. And even though it’s been 26 years of calling each other brothers and brotherhood, people were willing to listen and support and recognize that this is a way to include nonbinary members of the organization.

Stratton: It’s important for us as alums to provide insight, but for the organization to continue to embrace the values that made it so strong and sustain itself over the years, it needs to be a decision that lies within the body itself. If they believe it would benefit them by making a few minor changes in verbiage, I don’t think it will change the fundamental underlying mission and who we are.

Pemble: It’s always been a progressive organization. I think that’s what makes the Blazers stand out. And I think a lot of that has to do with the kind of students they attract. And it’s been that way since its inception. I think a lot of that stemmed back to the early ’90s, and people who were all fairly progressive, striving to be better, striving to break down stereotypes, striving to understand differences that people have with each other, and be more accepting. I believe that that foundation and those characteristics really helped put the Blazers on the right course, and the one that it’s on today.

Li: We’re just trying our best always to be more empathetic, be more understanding, and just support each other and build a community overall. I’m really excited about the fall class. I think these are all people that even through COVID-19 and even though there are no in-person activities, still want to be a part of this community and still want to invest in it. And I think that’s something that’s really cool, and shows me that there’s a lot of resilience through these times.

Patel: The thing that has helped us keep community alive is just being as normal as you can be, which I suppose is kind of weird enough in and of itself, because you can’t really be normal. But we still have our weekly meetings almost the exact same ways we used to, it’s just all over a virtual format, instead of in a big lecture hall. We still have one-on-one meetings. Instead of going to a coffee shop in person, it’s a Zoom call. And, I mean, there’s that issue with Zoom fatigue and kind of feeling a little bit less engaged over an online setting. But at the end of the day, it’s where we are and it’s what we’re doing and we’re just doing our best to be as normal as possible while still adapting to be safe.

Crawford: I can’t force it, you know. Let people make their individual connections, and then, when we come back, hopefully we can still try to rekindle some of the culture that we had before, some of the love that we had for each other before. I hope that’s how it will work, but I guess that’s just me being optimistic. I think college students are fairly good at overcoming obstacles, or at least, being apart for a while and then coming back even stronger after that? I think we’re fairly good at that.

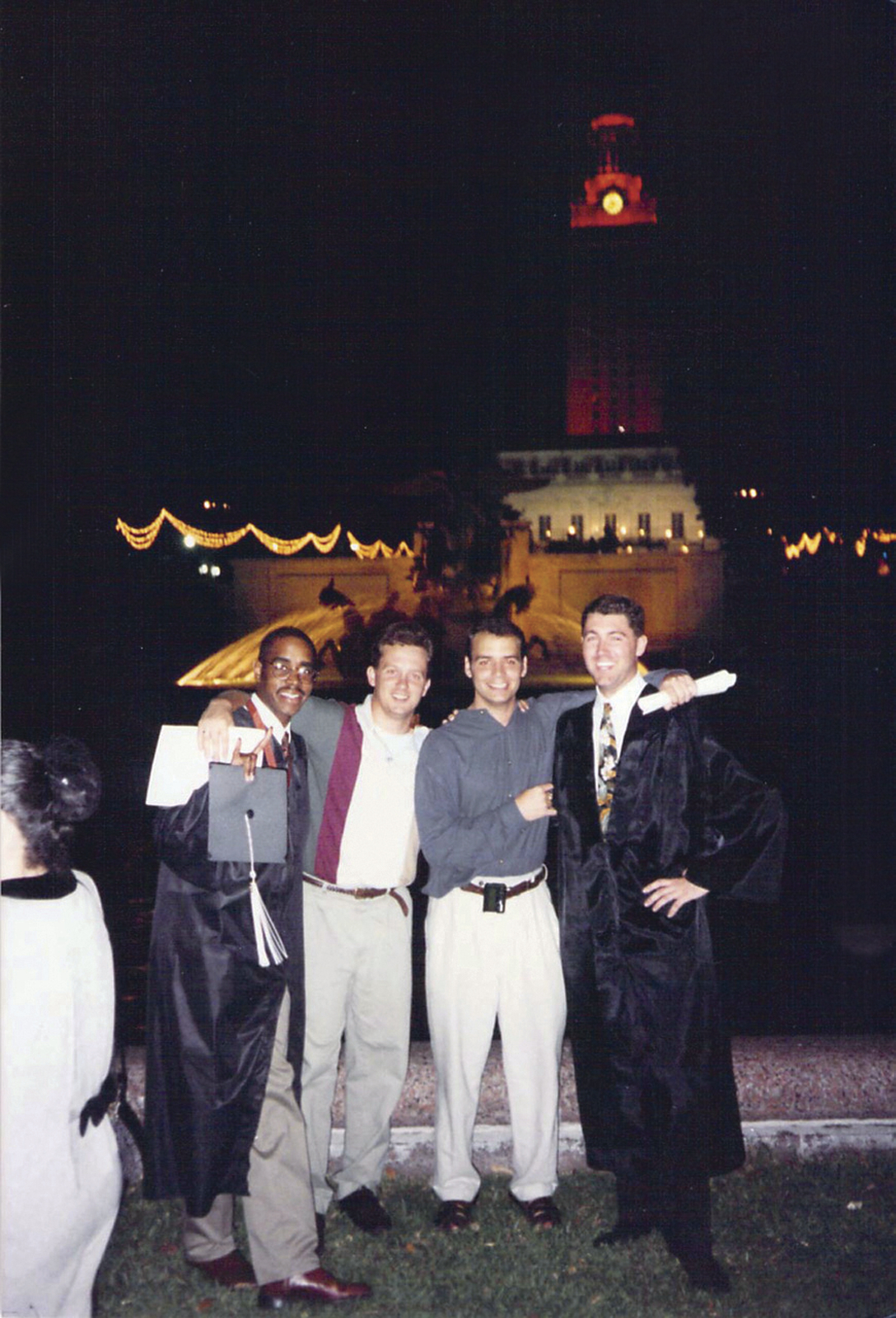

From top, photographs courtesy of Neal Makkar; Rich Reddick; Andrew Limmer; Neal Makkar