Robert Killebrew's Journey From Punishing Linebacker to Pain Reliever

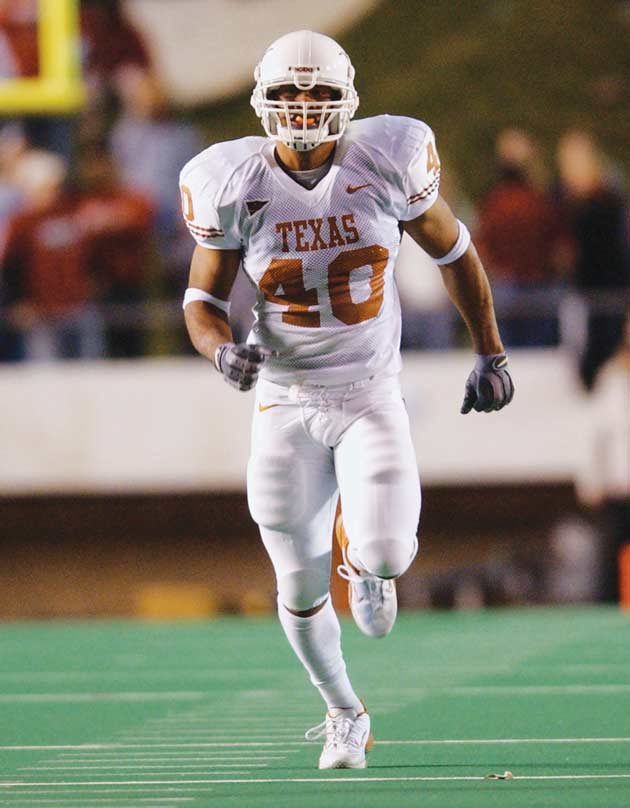

On YouTube, there is a highlights package featuring key plays from Texas linebacker Robert Killebrew’s career, sound-tracked by “Last Resort” by Papa Roach. Across the three-plus minutes of mid-aughts, pre-HD footage, Killebrew is a bulldozer, plowing into quarterbacks, demolishing punt-protection units, and stopping ball carriers in their tracks. As violent as football is already, Killebrew, BS ’07, who played outside linebacker for the Longhorns from 2005-07, seems to be playing a different, more intense version of the game. The only knock on his playing was that he sometimes craved that contact too much, to the tune of 15-yard personal foul penalties.

This portrait is wholly incongruous with the Robert Killebrew of today. Instead of being famous for taking running backs apart, he puts them back together, increasing their mobility after injury and reducing pain. Killebrew is a renowned physical therapist in Central Texas who works with NFL players, NBA athletes, cheerleaders, professional baseball players, and MMA fighters, among his list of almost 50 weekly clients.

Lots of college football players find a new career path when the glory days of the gridiron are over. But they are still, unmistakably, football players. While Killebrew brings a certain intensity to his current occupation, he is different than most veterans of the sport in that he knew exactly when to walk away.

“It’s when I realized I had more to offer the world than just my body and my ability to hit people hard,” he says on a video call in June, at the end of a long day before going home to his wife and two young daughters. “I was not good enough as a football player, but I was good enough as Robert. I had to dissociate between the two.”

Killebrew grew up in Southern California, the son of a pastor at a church in Compton. At age 10, the family moved to Spring, Texas, and in junior high, someone asked him if he’d like to play football. Unfamiliar with the sport, he says he was terrible at first.

“I was on the C-team,” he says. “Not even the B-team. I told my counselor that I wanted to quit, and she said she’d take me out of athletics.”

But the counselor went a different route. She called Killebrew’s mother, who responded that she didn’t raise quitters. In quick succession, players got hurt and he was moved up to the B-team, then up to the A-team, and he started to get on the field in key situations. He had to work to stay on the field, so by age 13 he was waking up at 6 a.m. to run, lift weights, and set up homemade drills in the backyard.

“I was horrible,” Killebrew says, “but I worked at it.”

By high school, Killebrew was a force at defensive end. His junior year, his coach told him he had a note in his locker. He thought he was in trouble. It was from Oklahoma head coach Bob Stoops, who was there to meet him.

“He told me, ‘I think you can go to college off this,’ shook my hand, and left. I didn’t even know this was a possibility. I was playing this to have fun with my friends and beat up on some people,” Killebrew says. By the end of high school, he had 60 offers, and his pick of anywhere he wanted to go.

He chose Texas for three reasons: academics, the competition at his position, and to be close to his family.

It felt like starting all over again once he got to the Forty Acres. He couldn’t crack the depth chart as a redshirt freshman, even as a highly touted recruit, because in his new position of outside linebacker, he sat behind one of the best defenders in the nation: Derrick Johnson. One practice, his position coach told him that they wasted a scholarship on him. Instead of shriveling, he just worked harder.

Killebrew eventually got on the field and never relinquished his starting role. Teammates, especially fellow defenders like safety Ishie Oduegwu, BS ’10, gravitated to him because of his intensity and leadership on the field and his approachability off it.

“Being violent, we shared that tenacity, that nature. But he was always cool, leading by example, being a positive force,” Oduegwu says. “I looked to him like a mentor … actually just more like a big brother.”

He won a national championship at Texas, and with his work ethic and natural talent, it appeared he’d be continuing his career in the pros. Life had other plans.

“I got picked up in a limo with Champagne and got dropped off on a school bus with a sack lunch. I thought I had made it. On the way home, I thought, This is how they did your boy.”

Last November, Killebrew joined the staff of Austin Physical Therapy, started by former Texas Longhorns trainer Cullen Nigrini, MEd ’04, who treated Killebrew during his playing days on the Forty Acres. It was a partnership they couldn’t have foreseen 15 years ago, especially because Killebrew had an arduous journey to his new path once he graduated.

After failing to make the NFL after tryouts with the Bears, Texans, and Seahawks, Killebrew retreated to Southern California with his college sweetheart (now wife) Kristin, whom he met while he played for Texas and she was a member of Texas Pom. In California, he became, in his words, “a surf bum,” working construction to make ends meet. That’s when the Calgary Stampeders of the CFL called. Soon after reaching Alberta, Canada, he realized that he had come to the end of his playing days. He looked in the mirror one day and said, “You’re not good enough.” That’s a difficult bit of self-awareness for a hulking national champion, a looming figure who quarterbacks saw in their nightmares. But once he realized his life didn’t have to end when the final whistle blew, he felt free. After a hamstring injury, the team let him go. He took the rejection as a positive omen.

“What we see as failures might be things saving us,” Killebrew says. “The way I played I am 100 percent confident I would have had CTE, if I already don’t have it.”

His father, in addition to being a pastor, was also an occupational therapist, which gave Killebrew an idea. He moved back to Texas and applied to the physical therapy program at Texas State. Once again, he was told he wasn’t good enough.

“They looked at my transcript and started laughing,” Killebrew says. He enrolled at Austin Community College for two years, working as a hospital tech on the side. He would wake up at 5 a.m., work until 2 p.m., attend class from 3-7 p.m., and study until midnight every day.

“It was a lot,” Killebrew says, pausing to collect himself. “I remember the [Texas State administrator’s] voice in my head, his face, every morning, getting up, working, learning, studying in between.”

Killebrew got straight A’s, took the GRE, and applied again to Texas State. He was once again turned away. A California school called St. Augustine opened a campus in Austin, so Killebrew took his transcript there, and was told to get his GRE score up and try again in another year. He waited, re-applied, and was put on the waitlist.

“That was a huge success to me—foot in the door,” he says. Shortly after, he was admitted. He was overwhelmed by how difficult and competitive PT school was, but he gutted it out, and after graduating with his doctor of physical therapy degree, he got in touch with former Texas running back Jeremy Hills, who had started a successful personal training business. He asked Hills if he could work with his clients as they trained for the NFL Combine, pro bono. That led to a business partnership and friendship that continues to this day—Killebrew gets athletes ready to take the field and Hills trains them.

“He’s my No. 1 source. I trust him with any athlete I work with,” Hills says. “The protocol is, before they work with me, they have to get cleared by him.”

At UT, Nigrini says, “Robert was known as an intense worker, in the weight room and on the field. He was full speed in everything he did.” Nigrini says that Killebrew brings that intensity to physical therapy every day. When Killebrew started at APT in November, Nigrini’s goal was to have his new hire eventually work with 40 clients per week. Within a few months, Killebrew was already averaging 45.

“People love what he is doing,” Nigrini says. “It wasn’t because of the internet or marketing. It was because he was doing good work.”

While Killebrew put his heart and soul into becoming the best linebacker he could be, he says he loves his new life. Besides, he still gets to connect with athletes like himself, aided by that tenacity he fostered and the credibility he brings to the job as a guy who has been there before.

“And I’m not in a cubicle,” he says, smiling. “I get to help people get better. I’m a servant. I couldn’t be happier.”