How a ‘Cactus’ Yearbook Helped One Longhorn Escape War-Torn Saigon

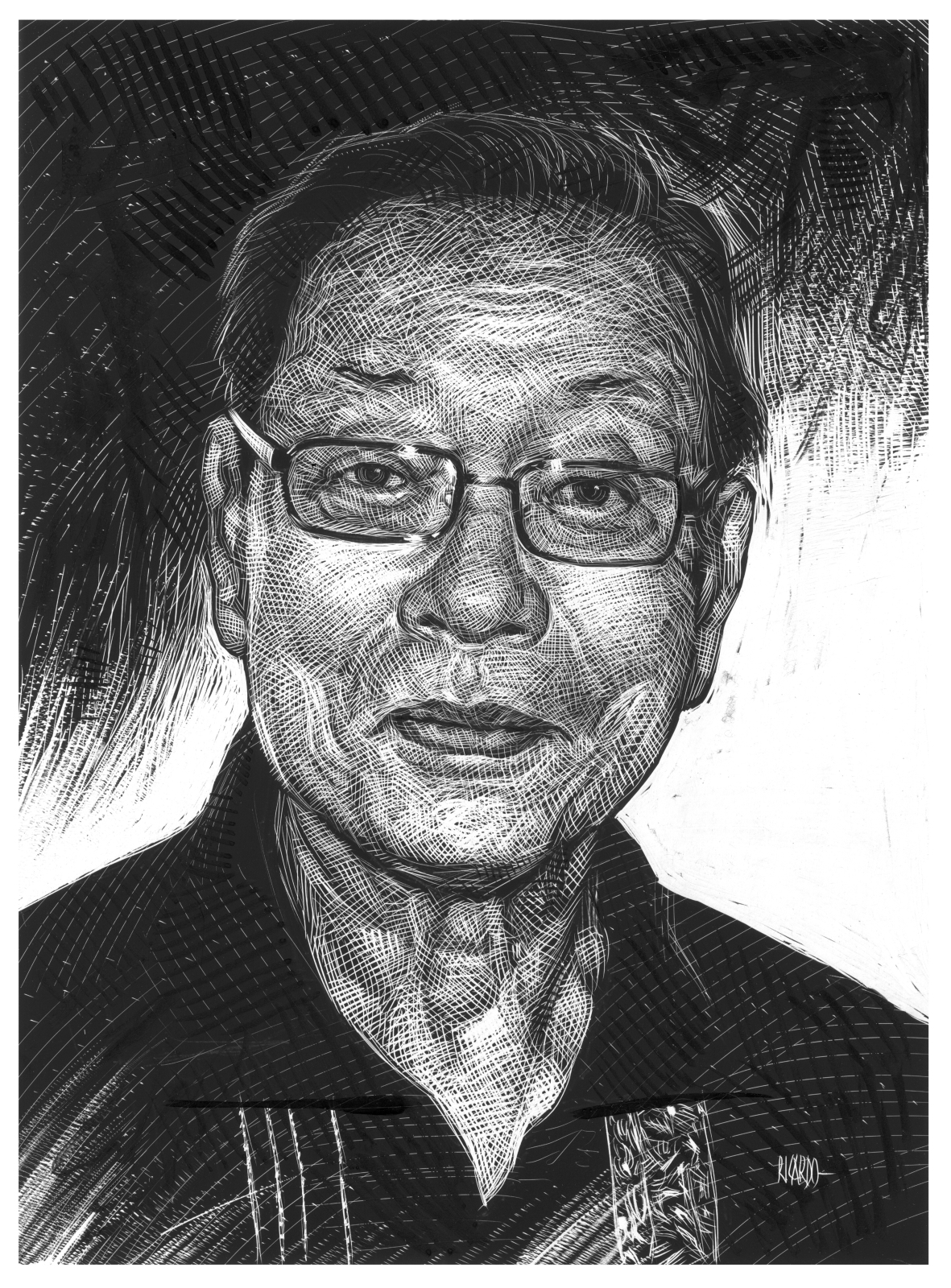

It has been an emotional Tuesday morning for Dean Hien Nguyen, MS ’73. The 90-year-old retired electrical engineer and I are speaking over FaceTime, his oxygen mask in one hand and his phone in the other. As he sits in his home in Sugar Land, Texas, where he has lived since 2001, I’ve asked him to go down a very old road with me. “Tell me about the day you escaped Saigon,” I say.

It was April 21, 1975, just nine days before North Vietnamese forces took control of Saigon. For nearly 20 years, conflict had been waging between the North and South. In the most simplistic terms, the U.S. had aligned itself with the South Vietnamese for fear that communism would spread to other countries, a justification that is still debated.

Nguyen, then 44, was a dean of the Vietnamese National Military Academy, an officer training school for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam in Dalat. He describes it as the West Point of South Vietnam, with only about a fourth of its population. He knew that Saigon, then the capital city of South Vietnam, was expecting a violent attack from the North. In anticipation, he headed to the United States Embassy to plead the case that he and his family needed to leave the country.

The impending attack, which would mark the war’s end on April 30, 1975, became known to most Americans as the fall of Saigon. Though that is a common way to refer to that day in communities of displaced Vietnamese, North Vietnam remembers it as the Liberation of Saigon, the day the country was unified. Like with all history, and the ways in which the truth is a matter of perspective, it’s complicated. And Nguyen’s experience is no different.

Nguyen was born January 1, 1931, in the mountains of Vietnam. He was the youngest of six children, four brothers and one sister. At 20 years old, while Nguyen was enrolled in a two-year electrical program at the National Technical School in Saigon, he was conscripted into the South Vietnamese Army as part of a program that drafted male citizens between 18 and 45. “They came to my school, called my name, and said, ‘You are being mobilized,’” he says.

Like three of his brothers before him, Nguyen remained committed to working for the military for most of his life. He was a South Vietnamese soldier who opposed the oppression of the communist North Vietnamese forces, but still hoped for the unification of Vietnam. He understood that fleeing the country meant saying goodbye to his home forever to start over in a land he barely knew. Still, he knew what he had to do. “I was high risk,” Nguyen explains. “I was a South Vietnamese soldier and supported the U.S. intervention. My family and I needed to go.”

Maybe it’s the pixelation of our video call, but Nguyen looks exceptionally good for his age. The skin around his eyes crinkles as he shuts his eyes to think, like he’s playing back footage in his mind that will help him remember. When he smiles, he smiles big, and his voice is clear and loud. While it’s sometimes hard to follow him, and his heavily accented English is occasionally garbled through the weak connection, Nguyen remembers every detail about the day he and his family left their home country. He runs through with me how they were picked up at a predetermined location, how they evaded enemy fire—and how an article in the Cactus yearbook proved to be his ticket out of Vietnam.

A few years before Nguyen fled his country for the U.S., he came to the states for a very different reason: to study electrical engineering as a student on the Forty Acres. It was 1971 and he was approaching 40 years old. At that time, he was still just a deputy dean of the military academy back in South Vietnam. The military had decided to “upgrade” their defense and selected eight officers to go abroad and advance their education.

The education program was partially funded through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Nguyen was given $10 a day for food, laundry, and books, while everything else was covered. Having left his family behind in Vietnam, Nguyen found himself a stranger in a strange land. That year on campus the Texas football coach was Darrell K Royal; tuition only ran about $60; and campus had become a demonstration hotspot for student activists who opposed the war.

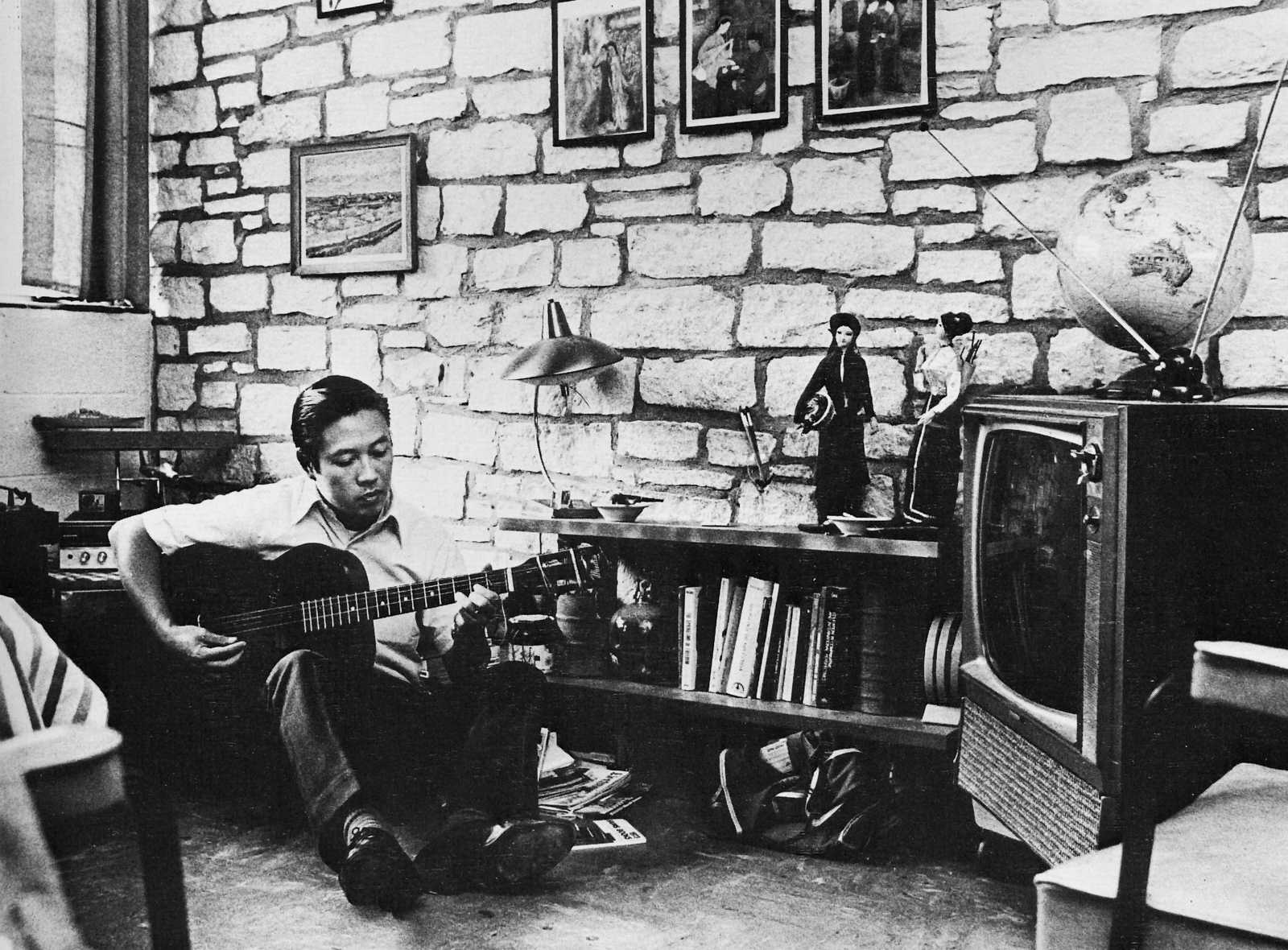

For the first couple of months, Nguyen stayed in an attic-like room of a small house that belonged to a woman in her 60s. “I enjoyed it,” he says. “Living in an attic in America was better than living in my own home back in Vietnam.” Eventually he moved into a small apartment with a roommate where he played guitar in his downtime. He remembers making certain cultural adjustments like learning to shake hands instead of hugging people when greeting them. He discovered a love for Texas football, but also experienced some bad: he remembers being on campus when a student threw themself off the UT Tower, one of nine incidents that led university officials to close the observation deck in 1975.

It was during this time that Nguyen met John Adkins, BA ’74, JD ’77, Life Member, who was a features editor for the Cactus yearbook, along with the late Elizabeth Daily Cohen, BJ ’74. They were searching for 10 students to highlight in the 1973 issue and Nguyen was the perfect fit. He served as the spokesman for the Vietnamese Student Organization, which he helped establish in 1972 and still exists today. And he was well-respected among his peers and faculty, which is why the UT International Department recommended him to be featured.

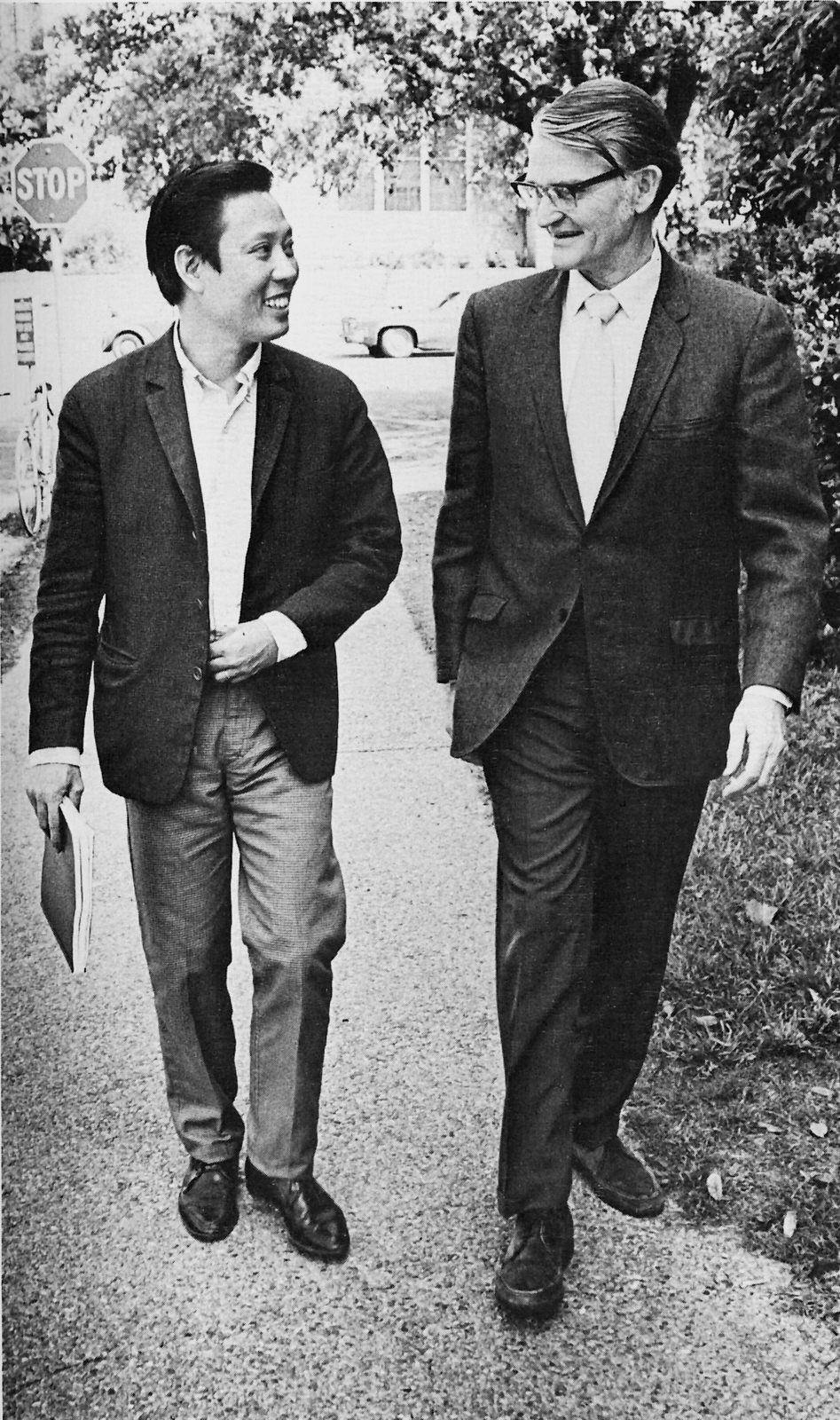

Earlier this year, Adkins, who is now a lawyer with Blank Rome LLP in Houston and a former Texas Exes president, was flipping through the 1973 Cactus and came upon Nguyen’s feature. It’s a two-page spread with photos of Nguyen working in a lab, meeting with his student organization, playing his guitar, and walking with his advisor Tom Anderson, whom Nguyen still talks fondly of today. A part of the feature reads, “[Nguyen] was impressed with the kindness of people—especially young ones. ‘My professors are always helpful,’ said Nguyen. ‘They work extra over time for their students.’”

Adkins marveled at Nguyen’s story and got curious. With a little digging, he found an address for one Dean Hien Nguyen in Sugar Land and wrote him a letter.

“I am writing to see if you are the same UT graduate who we featured in the 1973 Cactus yearbook at UT Austin,” Adkins wrote. “I’m interested to see where life has taken you the past 47 years.”

In the Cactus spread, Nguyen goes on record expressing his opinions on the war—a privilege not afforded to him in his country at that time and an almost-certain death sentence from the North. He said he approved of the U.S. troops in Vietnam but wanted them out. He felt that if the U.S. maintained its position, and the North showed goodwill, everything would work out for the best. “No one can say the Americans were dishonored,” Nguyen is quoted as saying in the yearbook.

Much to Adkins’ delight, Nguyen gave him a call and the two caught up about where life had taken them. “Talking to him in-person was mind-blowing after all these years,” Adkins says. “And hearing what he’s been able to accomplish? I’m really proud of him.” Adkins wasn’t sure if Nguyen would even remember the article, just a couple hundred words written nearly half a century ago. The now-68-year-old former Cactus editor was shocked at what Nguyen had to share with him: of course he remembered the article—it saved his life.

Following his graduation, Nguyen returned to South Vietnam, where the war continued. Over the next couple of years, he moved on from assistant dean to dean at the academy and continued to train soldiers. But as the impending attack on Saigon became clear, Nguyen knew he was in trouble. In the days before Saigon fell, he grabbed his Cactus and his degree and went to the U.S. Embassy to make the case that he and his family needed to be a part of the evacuation.

Nguyen even remembers the last name of the U.S. officer—“Mr. Jacobson,” he keeps saying—who gave him the green light. After looking at the book and the degree, Jacobson took out a piece of yellow paper and wrote the letter approving Nguyen and his family’s spot in evacuating. “I still keep that paper with me,” Nguyen says.

“Of all the things I meant to get around to this has meant the most to me,” Adkins says. “He thanked me for saving his life. But I told him that in truth, UT had saved it.”

The day the North Vietnamese troops took Saigon, the U.S. managed to successfully evacuate roughly 7,000 people, 5,500 of which were Vietnamese—and Nguyen was one of them. Americans and their South Vietnamese allies assembled at pre-arranged locations to board buses and helicopters before being ferried to U.S. Navy ships 40 miles away in the South China Sea.

Nguyen and his family were picked up in a U.S. military C-130 plane that then transported them to safety in the Philippines. About 10 days later, they were transferred to a U.S. military base in Guam then transported to a refugee camp in Arkansas where they stayed roughly a week. Nguyen sent his wife and daughter to California to work at restaurant while he and his son Joseph boarded a bus to Austin.

He called up his former UT electrical engineering professor Dr. Martin and asked for his help. Martin offered Nguyen temporary work house-sitting and let him stay in his basement. Nguyen eventually received help from his former adviser, Anderson, who took him for an interview for an electrical engineering position at the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA), which provides public power, manages the lower Colorado River, builds and operates transmission lines, owns public parks, and offers community services. Five days later, Nguyen got the call: The job was his.

Nguyen has never returned to Vietnam, where extended family still lives, and hasn’t seen the densely forested mountains in 50 years. But he has no regrets about his decisions.

He and his first wife eventually divorced, though he remarried 15 years later to a Vietnamese woman named Truc, who he met at a hair salon. All in all, Nguyen has seven children of his own, who are a testament to his hard work. He has two sons, Joseph, who went to Santa Rosa College in California and now works as a manager of a garage floor company, and Andy, who is a police office in the Houston area. His four daughters, all of whom attended the University of Houston, are Tran and Ngoc, who are both pharmacists; Chelsea, who is a cosmetologist; and Mylynn, who works at Expedia. Nguyen still loves to join in on the Texas football hoopla, though he hasn’t been back to campus in about a decade.

In 1980, Nguyen became a naturalized citizen, even changing his official name from Hien Nguyen to Dean Hien Nguyen. “I’m just so proud to have been the dean so I became Dean,” he says with a laugh. He seems to take pride in everything he works for, having stayed at the LCRA until his retirement in 2010. As he’s telling me about why he chose that name, he gets choked up and his voice quivers.

He says every time he speaks to a good friend or family member, he expresses his gratitude for the second chance at a life he got in America. “When I think about what America has given me, my education, my job, a happy life—that I can say if it is not a happy life,” he says, his brows furrowed, eyes tightly closed, “I cry and I cry and I cry.”

He thinks about all the American GIs who helped him escape. He says he is forever thankful for the sacrifices the thousands of soldiers made for his people. Whether it was a war the American public supported or not, it resulted in the deaths of more than 3 million Vietnamese and American people. It is considered one of the most violent conflicts in American history and is still a major point of contention nearly 50 years after U.S. troops left. While Vietnam refers to it as the American War, the U.S. teaches this event as the Vietnam War. Whichever way you look at it, the war shaped the course of history for two nations and the lives of millions of people who lived through it.

As he gathers himself, he notes that his mother and father died relatively young, at ages 65 and 70, respectively. He says he could have never imagined he’d still be around this long. “And the next time you call me, I expect to answer the phone again,” he says. “I believe I’m OK. Thanks to America.”