What Does it Mean to Be a Longhorn Fan in 2020?

Seven years ago, I attended my final UT football game as a fan; six or so months later I joined the staff of the Texas Exes and began covering football games from the lofty press box. Ole Miss was in Austin, ready for revenge on the back end of a home-and-home series that had previously seen an almost-perfect Texas quarterback David Ash demolish the Rebels the previous year. Still a couple years away from beer sales at Darrel K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, I joined two friends, both lifelong Longhorns, in an age-old tradition: throwing back as many as possible before walking through the gates.

The game was mostly a bust; though Texas headed into the locker room at halftime with a 23-17 lead, Ole Miss dominated the second half, coinciding with our buzzes wearing off and a group of Rebels fans chanting “SEC! SEC! SEC!” in the row in front of us. I can’t recall one specific play from the game, but I will never forget how I felt that day. I remember the great seats we got from a friend’s dad, near midfield in the lower section on the Texas side, so close we could make out every player. I remember high-fiving my friends and making fun of the Oxford boys and their navy polos tucked into plaid shorts every time they’d turn around. Texas, my adopted college football team, didn’t even win, but the postgame margaritas and beef special nachos at El Patio still tasted like heaven. Even the diehards smiled and clinked glasses after a bad loss. This is what fandom is. I miss it more than anything.

I haven’t sat in those stands for years, but this moment, once recessed deep in my memory, glitters and gleams now that it cannot exist. I can’t imagine this scenario today—for a few reasons. Mostly, I can’t fathom cramming into the lower bowl (or the nosebleeds at the Erwin Center or anywhere inside Gregory Gym, for the matter) during or post-COVID-19, nor will I high-five anyone outside my immediate family for a very long time. Eating inside a packed Tex-Mex joint, elbow-to-elbow with sweaty Texas fans? Sounds divine, but it couldn’t be me.

Will fans still embrace after Texas touchdowns post-pandemic? Will they sing “The Eyes of Texas” as a united crowd ever again, after the demands this summer from student-athletes to remove it based on its racist origins? As Longhorn Nation has faced one of the most divisive periods in its history, they’ll have to look inward and consider what it means to be a Texas fan in 2020 and beyond.

Marc Pña, BJ ’01, remembers where he was when his world stopped spinning. As the leader of Occupy Left Field, the band of devotees who transform the outskirts of Disch-Falk into a party every spring, Peña lives and breathes Texas baseball. The father of a 3-year-old daughter with his wife of 15 years, he plans his life around the season, and that’s not to mention his affinity for football, basketball, and other Longhorn sports.

He was with the usual crew on Wednesday, March 11, watching Texas dismantle Abilene State on the way to a 14-3 record, feeling joyous about Texas’ best start in a decade. But before the umpires called the last out, the COVID-19 dominoes began to fall around the world. Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson announced they tested positive. Jazz center Rudy Gobert followed, and the NBA swiftly postponed its season. Peña tweeted, from the OLF Twitter account: “It’s OVER guys . . . ALL sports are over for the season after tonight. Prayers up, folks,” followed by a hook ’em horns emoji.

The next few days were a whirlwind for the OLF crew, as the season was swiftly suspended and then canceled. That Saturday, they gathered to say goodbye to the season. They got the group together, including some parents of current players, to play whiffle ball, drink a couple beers, and get a bit of closure.

When I speak with Peña over the phone this summer, he has come to peace with the lost 2020 season. He is happy, at least, that the NCAA granted some players an extra season of eligibility and that the team might look even stronger going forward with immense depth. But as Texas has swapped places with New York to become a hotspot of the pandemic, of which there is no clear end in sight, he is beginning to worry about football, basketball, and, unthinkably, the 2021 Texas baseball season. Could his tailgating plans—for which he has already placed a deposit for his usual spot on the LBJ Lawn—vanish into thin air? Will DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium be empty as Sam Ehlinger completes his senior season? Will he get a senior season?

As the summer races to a close, Longhorns around the world, normally galvanized by the promise of another fresh start for Texas football, stand bewildered. What will fandom look like this fall? Next spring? Will it ever be the same again? As you read this, you know much more than I do; the virus is unpredictable and finds new ways to shock on a daily basis. This moment of uncertainty has caused a legion of Longhorns to reflect on what it means to be a fan.

“I’ll be heartbroken if we lose another season,” Peña says. “Or if they have to play in front of no fans.”

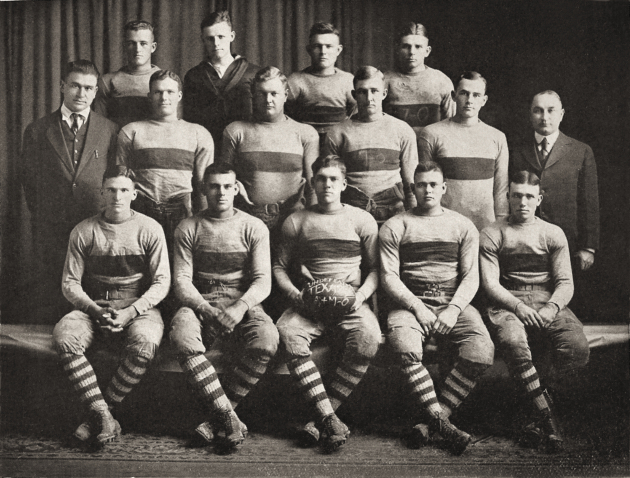

While it's easy to turn to history to consider what might happen next, it’s important to note that the implications for a mostly canceled 1918 Texas Longhorns football season vastly differ from the harsh reality that would follow one this year.

But the allure of symmetry—the so-called Spanish Flu and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a century and change apart—is relentless. Since college sports have existed, there have been only two catastrophic virus outbreaks that have seriously threatened the very idea of gathering in public to cheer for an alma mater.

The front page of the Nov. 4, 1918, edition of The Daily Texan featured a curious headline: “Longhorns Keep Record Clean by Swamping Ream Aviators.” No, Ream Aviators is not a defunct nickname for Texas A&M; because of the pandemic sweeping across the globe in 1918, Texas was forced to pivot away from its normal schedule, forgoing games against regular opponents Oklahoma, Baylor, and Arkansas, and replacing them with exhibitions against the Radio School from nearby Penn Airfield, Camp Mabry Auto Mechanic School, and a team called Ream Flying Field, composed of commissioned pilots from Houston.

While Texas ran the table in 1918, giving up only 14 points, the entire season gets an asterisk, and only partially because the Longhorns’ opponents were well below the caliber of the teams in the Southwest Conference. Despite hosting eight home games out of nine possible matches that season, there was barely anyone there to watch.

On Oct. 13, Penn Radio College played its first of two consecutive games against Texas at the first version of Clark Field, at the corner of Speedway and 24th Street. Capable of holding 20,000 screaming fans—the largest such stadium in the southern United States at the time—only 500 people showed up, according to The Daily Texan. It’s unclear if social-distancing guidelines necessitated the small crowd or if fans were scared to cram into the bleachers, but the result is the same: While Texas didn’t lose an entire season, it lost the spirit of the whole thing. No undefeated record or world-beating defense can suffice in a tree-falling-in-the-woods scenario.

Following the same math, the stadium at 2.5 percent capacity would mean roughly 2,500 Texas fans in the stands next year. (If fans are allowed at all. Some college and NFL teams have already announced they will play home games in empty stadiums.) You can even multiply that percentage by 10 because of the enlarged fanbase and Americans’ increased collective obsession with football over the last century. Say there are 25,000 people spread across the stadium like little ants when Texas hosts Iowa State on November 21 locked in for the Big 12 Championship. I’d venture to say that still might feel like a lost season, no matter the team’s record.

Newly bearded UT Vice President and Athletics Director Chris Del Conte has been the eternal optimist during the pandemic. While at press time, the full plan for fall sports is not yet available to the public, the athletics department is preparing for a multitude of scenarios: a full schedule, an altered schedule, half-full stadiums, a delayed season, a canceled season.

“I’ve heard ’em all,” Del Conte said to the Austin American-Statesman in early July. “I don’t think anything is off the table.” On July 20, Texas announced, in a letter to season ticket holders, it would allow just 50 percent capacity at the football stadium. Before the month was over, the UT System Board of Regents asked the university to explore capacity at 25 percent and the SEC decided to go to a conference-only schedule, wiping out the marquee rematch between Texas and LSU in Baton Rouge this fall. On Aug. 3, the Big 12 voted to go conference-only plus-one, which will eliminate either the South Florida or UTEP game. At press time it is unknown who Texas will open the season against, when its season will begin, and how many people will be allowed inside the stadium to witness it.

Former Texas wide receiver Quan Cosby, BSW ’09, is—if it’s possible—more optimistic. When we talk in late June he can’t even begin to imagine what he would do if he were still a student-athlete, having to navigate training plus online classes from his parents’ home.

“If you tear your ACL and can’t play that season, you still see your boys play,” Cosby says. “Now it’s like the whole team got injured. 2020 has poured it on like nobody’s business.”

But he dreams of seeing Texas play this fall.

“Even if it’s 25 percent in that stadium, which is weird, as long as they can play, we can tailgate at home,” he says. “Maybe by the end of it we have a vaccine and we can fill up a big stadium for a playoff game.”

As if the pandemic wasn't painful enough, the debate about the university’s alma mater, “The Eyes of Texas,” raged through June and into July.

UT Austin football players joined the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests in June, marching on the Capitol beside members of the Austin Police Department, which was generally seen as a show of unity. A week later, on June 12, a group of UT athletes released a list of demands to the athletics department and the university, with the stance that they would not recruit players or participate in donor events until an official commitment from the university. The list sent shockwaves through Longhorn Nation. Two points were especially divisive: a substantial yearly donation to Black Lives Matter and the retiring of “The Eyes of Texas,” due to its origins at a campus minstrel show and association with a quote by Confederate general Robert E. Lee.

Cosby says he thinks the players are courageous for speaking out, and also commends new Interim President Jay Hartzell’s, PhD ’98, Life Member, handling of the issues so far—in addition to being thrown into the fire as COVID-19 rages in Texas. Some of the items on the list were, to him, a pretty low bar for the university to clear.

“Some of the Confederate stuff, at some point, we’re going to have to move on. They lost, thank goodness,” Cosby says, with a laugh. “I’m certainly on board with getting rid of that BS because UT is better than that.” As for the alma mater, he says players in the locker room when he was at Texas were aware of the origins of the song, but he never saw an organized movement to get rid of it from a player perspective, though the genesis of the song has been known for years.

“The Eyes of Texas” is a much thornier issue than any other demand on the list; the emotion wrapped in it is undeniable. Cosby tells me that a friend called him after the athletes released their demands because he desperately wanted to just have a conversation about “The Eyes of Texas.” He sang the song every night to his children and it was woven into the fabric of his identity as a fan and alumnus, as it is for hundreds of thousands of people.

“I told some of the players, ‘That song is not a football song, it’s a school song, so be empathetic to what everyone feels about it,’” Cosby says.

Many Longhorns on social media and in calls and letters to the university and the alumni association voiced the opinion that “The Eyes of Texas” was being needlessly vilified.

“I’m proud of them for using their voices,” UT Austin History Professor and Vice President for Diversity and Community Engagement Leonard Moore tells me. “For too long, college athletics has had a ‘shut up and dribble’ ethos.”

Peña, who full-heartedly supports the student-athletes, hopes that the demands do not snowball.

“I’m very supportive of athletes and minorities. I’m Mexican-American so I can see where they are coming from,” he says. “I am in the athletes’ corner, but I hope the community comes together and approaches this holistically so that it doesn’t cause a division between athletes and students or athletes and fans.”

Junior defensive backs Caden Sterns and DeMarvion Overshown were among the most vocal proponents of change and social justice on the football team and continued to use their platforms to compound the message the athletes had sent to the university. In the ensuing weeks, Overshown repeatedly called for the removal of “The Eyes of Texas” and Sterns tweeted, “Can’t be so attached to traditions that you’re afraid to create new ones.” On July 10, Olympic gold medalist and Longhorn track and field alumna Sanya Richards-Ross, ’05, published a piece on Elle.com, calling for the song to be banned.

A month after the student-athletes made their demands known, the university responded. Just before noon on July 13, Hartzell released the university’s response via email and social media, in some cases agreeing to the changes. The university made plans for expanding the recruiting of Black students outside Austin and diversifying the faculty, taking Robert L. Moore’s name off the campus building that houses the astronomy, physics, and math departments, and honoring Texas’ first Black varsity football player Julius Whittier, BA ’74, MPAff ’76, Life Member, and the Precursors—the first Black undergraduates at UT—in a variety of physical ways. Other campus landmarks and buildings, like the Littlefield Fountain, the Gov. Jim Hogg statue, and the Belo Center, will not be renamed. Additionally, upon request of the Jamail family, Joe Jamail Field will be renamed Campbell-Williams Field in honor of Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams. While the demands were all significant, and some have wide-ranging potential to change the face of the university, everyone who opened that email scanned all the way to the bottom for the hot-button issue: the song.

Ultimately, “The Eyes of Texas” will remain the alma mater for the university. Hartzell wrote in a statement that UT will “own, acknowledge, and teach” about the song’s origins.

“It is my belief that we can effectively reclaim and redefine what this song stands for by first owning and acknowledging its history in a way that is open and transparent,” he wrote.

Not every Longhorn fan felt the university’s response went far enough—and some felt it went too far. But, at least initially, a few of the players involved in creating the list of demands appeared satisfied with the university’s response. Overshown and Sterns wrote, “We are one!” and “Great day to be a Longhorn . . . Looking forward to making more positive change on campus,” respectively on Twitter.

Moore, who chairs the Campus Contextualization Committee for UT Austin symbols and monuments, tells me in late June that he didn’t fear a great uprising from fans regardless of what the decision would be.

“We’ll be alright. UT fans want to act like they are LSU or Alabama fans, but our fans are nice,” he says. “I think the fans need to realize that this is a new day, and if student-athletes using their voice upsets you, then ask yourself why it’s upsetting to you.”

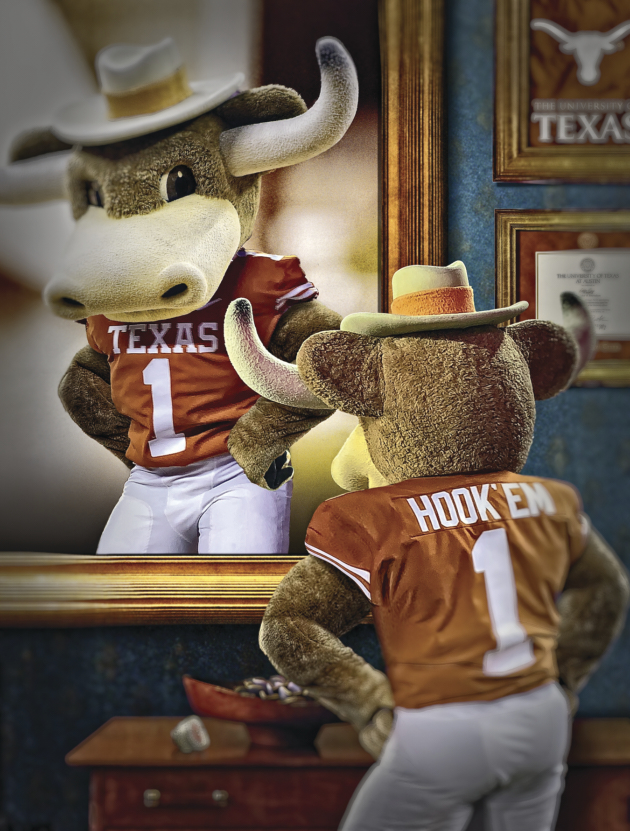

As a former four-year member of the team that dons the Hook ’Em mascot costume for hundreds of events every year, Hannah Willard, BA, BS ’20, felt the intense connection between Texas players and fans, often acting as a conduit between the two groups.

On March 13, she was visiting some fellow mascot friends in Virginia when she felt the brunt of what was happening. She was in a restaurant with her father the night before when he looked up from his phone and told her that the rest of the Big 12 season was canceled. That weekend in Virginia, friends and family begged her to hop on a plane back to Texas before she got stuck far away from home. On her way back, the airport was eerily empty, a far cry from how full it was just a few days before. It drove home an already emotional moment for her: passing the torch to the next class of mascots.

“I knew it would come to an end but the night they canceled the season it was very emotional for me,” she says. “My brain wanted to shut down over it.”

Having been a mascot since high school and wanting to continue her career after Texas, it was like the rug had been pulled out from under her. One day she was Hook ’Em and the next day she wasn’t. She takes the responsibility of being a great uniter of Longhorn Nation and one of the key aspects of Texas fandom on gameday very seriously.

“I love making other people happy, performing, getting to make jokes, and getting to be a part of something bigger than myself,” she says.

She loves it so much that, even acknowledging that sporting events aren’t safe to attend in large groups yet, and that Hook ’Em attracts large groups of people to crowd together, she’d probably jump right back into the costume if asked.

“Knowing myself I probably wouldn’t say no,” she says. “Do I think it’s the safest thing for the people there? Probably not.”

Peña and OLF have already started thinking about what their fan operation looks like after the pandemic.

“We might have one person responsible for handing out beers instead of everyone reaching into a cooler. If we’re serving food, maybe we’re having one person serve that instead of people helping themselves,” he says. “We will make some small adjustments but my hope is by spring of next year, I’m praying that things are going to be back to normal and at a baseball game [COVID-19] isn’t the first thing that crosses my mind.” That bottle of Fireball they normally pass from fan to fan for good luck has already been replaced with airplane bottles. Anything to re-focus on what brought them there in the first place: their love of Texas sports.

So, what does fandom look like in 2020? While the hero shots of Gregory after the volleyball team wins a set or Sam Ehlinger takes a keeper around the corner at DKR might not look familiar for a year or two—or more—what makes fandom intrinsic to the Texas experience is the Texas fan. If you’re reading this particular magazine, you can glean what fandom looks like in 2020 by glancing into a mirror.

Cosby, who has bled for the Longhorns for years, empathizes with the athletes and the fans, and longs to be among both as soon as possible. He also illustrates a point about fandom that the many fans, former players, administrators and stakeholders echo: Regardless of what the stadium looks like this fall, next spring, and beyond, the issues aimed at the heart of the common fan right now will dissipate with time and concerted effort.

“I’m a mask guy,” Cosby says. “I’ll stand on the sideline and cheer my boys on in a heartbeat.”

Covering the Longhorns these last six-plus years has changed how I look at all sports. Spending Saturdays in the icy-cold air conditioned press box, showing up hours before a volleyball match at Gregory to scope out the scenery, and waiting for the opposing coach to emerge from the locker room inside the Frank Erwin Center is like watching the sausage being made. I am suspicious of management and the company line because I have to be, and that permeates every aspect of my sports viewership. In the same way, I think, those of us who are “sportswriters”—and I am less so than the dozens of reporters on the UT beat full time—sometimes lose the fan perspective. We all shed the unconditional love that most Longhorns have.

But that doesn’t mean I can’t witness it, albeit more infrequently than before.

Another favorite Texas football memory of mine comes in a loss, this time well into my time covering the team. It was my first trip to Dallas to cover the Red River Showdown, in October 2016. A couple of friends got free tickets but were unsure if they wanted to trek up to the game; they didn’t even have a place to stay. In the middle of the night before the game, I woke up to a series of texts from them, letting me know that they were coming. Both lifelong Texas fans, neither had experienced a Texas/OU game before.

I covered the game from the auxiliary press box, a depressing outdoor area directly behind a sea of Oklahoma fans. The WiFi didn’t work, the game was boring (from what I could see, when my vision wasn’t blocked by waves of crimson), and it was hot. After the postgame presser, I met up with my friends, who had front-row seats to see Texas fall to 2-3 on the season. They were bummed, but their moods soon flipped. As we walked out onto the concourse of the State Fair of Texas, they found community.

One friend wore a vintage corduroy Longhorns hat; every third Texas fan (and one OU fan) either asked where he bought it or offered to purchase it directly off his head. As we settled on a patch of grass, Fletcher’s Corny Dogs and plastic cups of beer in hand, they commiserated with their brethren. They joined in conversations with strangers on the lawn, complaining about the referees and play-calling, repeating phrases like, “If we just had two more minutes, Oklahoma would’ve been cooked!”

The “we” is important there. As tacky as it sounds sometimes—almost no one who uses the pronoun is suiting up for Texas anytime soon—it invokes the sense of community that Texas fans lack right now. Even among enemies, the tension cooled; two older OU fans spent an hour complaining about their team’s defense and extolling the virtues of Braum’s whole milk (“It tastes like a milkshake!”). Everyone was full of fried cheese, half-drunk, and, a win or loss on the brain, happy just to be there. We’re probably losing that communal experience, no matter what happens, at least for a while.

There is much more that we have lost—and will continue to lose—as our world is mutated beyond recognition by this virus than watching Texas play Oklahoma among the odor of the grease traps. Hundreds of thousands of people have died from COVID-19 and millions more have lost their livelihoods. Losing sports seems like small potatoes, in the scheme of things. But what’s really lost here isn’t found on a box score or in a highlight video. Because it is baked into identities, it feels like there is something to mourn; it’s like a phantom limb.

If that seems macabre, fear not; 100 percent of doctors agree that it’s just a surface wound.

When I talk to Peña about what Texas Fandom 2.0 looks like, he says that this moment might be a positive experience for Texas fans, when it all shakes out. He and the OLF diehards had a conversation recently where they realized that maybe they took some home series and mid-week games for granted.

“Now that people have been stuck inside for half a year, I think there’s going to be people to be hungry to see a game in person,” he says. “I think you may see more people out there to make up for lost time.”

Whether everyone is aligned on what to sing—or to sing at all—after a Texas game, or whether fans are willing to embrace one another like old times is yet to be seen. Regardless, they will unite. They always do.

Illustration by Eddie Guy

Photos courtesy Marc Peña; the Cactus yearbook; Texas Longhorns