This UT Alumnus Is Building Space Hotels

At any given time, there are a half dozen humans zipping around the Earth at over 17,000 miles per hour. These are the lucky few chosen to live and work on the International Space Station (ISS), the world’s premiere orbital laboratory. It’s a far cry from the future envisioned in Stanley Kubrick’s magnum opus, 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Hilton space stations accommodate travelers on extraterrestrial business trips. But if Michael Suffredini has his way, the stuff of science fiction may soon be a reality.

As the president and CEO of Axiom Space, Suffredini, BS ’83, is a bona fide hotelier for the space age. His mission is to build the world’s first commercial space station, which would provide scientists and wealthy adventurers a luxurious place to rest their heads during jaunts to low Earth orbit. These astro-tourists would hitch a ride on rockets operated by companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, whose self-landing rockets are rapidly reducing the costs of getting to space. But a ticket is still pricey. This March, Axiom inked a deal with SpaceX to send three private astronauts on a mission to the ISS next year—the price tag for each seat was set at $55 million.

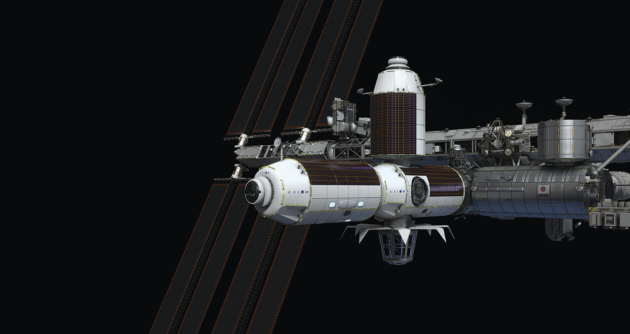

Space stations have grown in size over the years, from the one-room Skylab in the 1970s to the sprawling ISS, completed in 2011, which stretches the length of a football field and can host up to seven people at a time. But the basic design principles are essentially the same. A space station is a giant, pressurized metal can, equipped with all the life support systems an astronaut needs in orbit. It harvests its energy from the sun, it circulates oxygen, and it can even recycle an astronaut’s urine for drinking water. Space stations are too big to launch in one piece, so they’re typically designed as an assembly of modules. Each module is launched separately and then assembled in space by astronauts and specially designed robotic arms.

Today, the ISS is the only place in the solar system capable of sustaining humans in microgravity. It was a 12-year, 15-nation construction project led by the U.S. and Russia and cost $100 billion. Houston-based Axiom, by comparison, is a 5-year-old company composed of just 60 people. Its vision for a commercial space station sounds quixotic; Suffredini says it’s inevitable.

He spent 27 years at NASA, and a few years before he left, his boss told him they weren’t going to build another space station after ISS. "He said we were going to cede it to commercial companies,” Suffredini remembers.

It’s only fitting that Suffredini, who has spent his entire professional career keeping humans alive in space, should lead the way into the next chapter of crewed space exploration. After graduating from UT Austin with a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering, Suffredini went to work at the former aerospace company McDonnell Douglas, which was contracting with Johnson Space Center’s mission operations center. At the time, the ISS was just a glimmer in NASA’s eye. Instead, the agency was focused on Freedom, a Reagan-era plan to build an American space station. But by the mid-’90s, the plans for Freedom were abandoned after repeated budget cuts to the program and NASA pivoted its focus to what would become the ISS.

Suffredini spent about seven years with the agency working on the space shuttle program. In 2005, Suffredini took the helm as manager of the ISS Program, a post he held until his retirement from the agency in 2015. His history of managing crewed operations in space made him a good fit for overseeing the complex web of operations that comes with running a laboratory 250 miles above the earth.

“We built the space station, operated the space station, and sustained the space station,” Suffredini says. “It was an all-inclusive job, but it was a heck of a lot of fun.”

Shortly after leaving NASA, Suffredini founded Axiom in January 2016. A few years later, the company is already leaving its mark. In January 2020, Axiom won a competitive NASA contract to build a new commercial human-rated space station habitat that will attach to the ISS. It will consist of several modules, each with a specific purpose. There will be a living space for the crew, a research and manufacturing facility, and a glass-paneled Earth observation room designed to give its inhabitants a panoramic view of the planet zipping by hundreds of miles below. Suffredini expects Axiom’s modules to begin arriving at the space station in 2024, to be used as additional space for research, manufacturing, technology testing, deep space exploration systems demonstration, and living space for private and professional astronauts.

Axiom’s crew quarters are positively luxe compared to the spartan accommodations of the rest of the ISS, where enabling cutting-edge research took precedence over comfort. Sprung from the mind of the famed French designer Philippe Starck, the module’s walls are covered with white padding and illuminated with color-changing LEDs. Its chic futuristic aesthetic speaks to the changing requirements of the new space race, where researchers and thrill seekers will live side-by-side in microgravity. It’s no longer sufficient to simply provide astronauts with a workplace; Suffredini is betting on space tourists expecting some of the pampering they get at five-star hotels down on Earth.

“We didn’t want to just be a bunch of space nerds building a space station,” he says. “We wanted to build a safe station that is fun, comfortable, and luxurious.”

Axiom’s headquarters is located on the outskirts of Houston, just down the road from NASA’s Johnson Space Center, best known as the stomping grounds for astronauts in training. It’s a prime location for the company, which will be working closely with NASA’s human spaceflight experts as it prepares to launch its crew module into orbit. The shell of the station is being built by the French aerospace giant Thales Alenia Space, which also built nearly half of the module shells for the ISS. Once the shells are ready, Thales will ship them to Axiom, where engineers will add the rest of the components to the inside and outside of the space station modules.

Unsurprisingly, building a human space habitat is an extremely complex process. It’s like simultaneously building a hotel room, laboratory, and factory that can fit inside a space the size of about three average American houses, survive the hostile space environment, and meet NASA’s exacting engineering requirements.

Once its hardware is ready, the station modules will undergo rigorous testing. This involves making sure modules can handle the intense environmental conditions they will experience on their way to space and once they arrive, as well as simulating the way the modules will work with the ISS. The first time the modules will connect with each other is in space, so it’s imperative to get it right beforehand.

Axiom plans to deliver its first module to the ISS in just four years. The company’s astounding progress can be attributed to its engineers’ extensive background in NASA’s human spaceflight program and the fact that Suffredini is perhaps the world’s foremost expert in zero-gravity hospitality.

Suffredini’s extensive experience will come to bear as Axiom takes its first steps toward a free-flying commercial space station in the coming years. The ISS is only funded through 2024, and although there have been talks to extend its lifetime to 2028 or 2030, at some point in the near future it will either be decommissioned or sold to a private operator. Suffredini hopes that Axiom’s module will be ready to separate from the ISS to operate as an independent outpost by then. Although Axiom’s space station will be open to tourists, he envisions it also being used by researchers from NASA and other government agencies. By offloading the operation of low Earth orbit space stations to the private sector, Suffredini hopes it will free up resources for government agencies to focus on less commercially viable missions, like the exploration of deep space.

The plan to build commercial space stations is almost as old as human spaceflight itself. The idea was first seriously floated during a conference about space tourism in 1967 by none other than Barron Hilton, the son of the hotel magnate Conrad Hilton. He envisioned “Orbiter Hiltons” that would be 14 stories tall and able to accommodate up to two dozen people at a time. “Now that may sound like a pretty small hotel,” Hilton told his audience, “but my father’s first hotel in New Mexico only had 10 rooms.”

More than 50 years after Hilton’s visionary speech, space hotels remain a distant dream. But Suffredini says a confluence of technological factors, particularly the advent of reusable rockets pioneered by companies like SpaceX, have made the concept viable for the first time. Suffredini is hardly the only one thinking about expanding human habitats in low Earth orbit. The billionaire hotelier Robert Bigeow sent an inflatable habitat to the International Space Station in 2015 with an eye toward creating a standalone space station. There’s no word yet on whether a stay at these orbital outposts will include pillow mints, but it seems like it’s only a matter of time until Earthlings can start booking their extraterrestrial vacations.

Photos courtesy of Axiom