Back to School: Learning How We Talk About Gender

This past spring, I donned my pink backpack festooned with enamel pins and began my cross-campus trek from the Etter-Harbin Alumni Center to the CMB—a walk so familiar, I expected to lock eyes with my college crush as I made my way across the Main Mall. Glancing toward the Tower, I marveled to myself that some things never change, and texted a photo to my dad (we have three UT degrees between us). “Hook ’em” was his prompt reply.

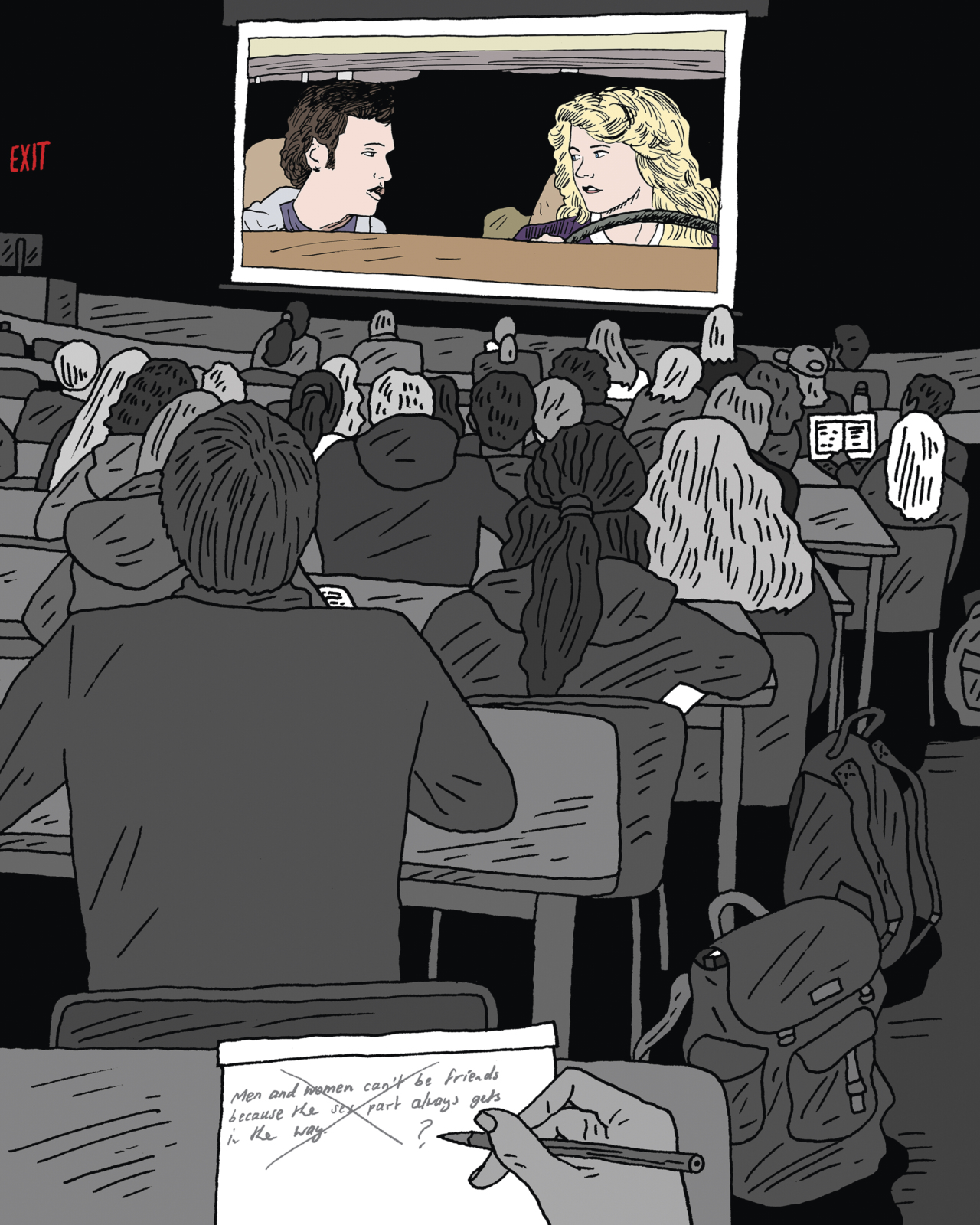

My journey led me to UT associate professor Johanna Hartelius’ Gender and Communication course, which explores the attitudes surrounding gender in culture. Hartelius and I are newly neighbors, and as our kids played over the prior weekend, we struck up a conversation about her class, which she has taught at UT for two semesters. In it, she encourages her students to think critically about the language we use to define gender in our society—and for me, hoping to raise an empowered and compassionate daughter, managing a co-ed team, and striving to evolve as a human, the topic felt not just timely, but imperative. She graciously invited me to attend. “You might think it’s a blow-off class,” she laughed. “I’m lecturing about When Harry Met Sally. But I promise we’ve covered a lot of intense stuff leading up to it.”

Reading through the syllabus, which includes redefining what’s feminine or masculine, intersectionality (that is, the ways in which gender creates overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage), and gender and communication in the workplace, I got a sense of what she meant.

I found a seat in the lecture hall and looked around, wishing I’d sprung for gray coverage at my last hair appointment. As Hartelius launched into the lecture, she casually rattled off the phrase, “cisgender heteronormative framework.” If I thought I’d been open-minded and expansive in the early aughts, well, the bar had since raised.

Later, when I ask Hartelius what it’s like to teach this subject in 2019—when language like “patriarchy,” “women’s issues,” and “transgender” is across all media—she says she’s seen some eyes roll. It’s that, “oh, come on reaction” when she points out even the most subtle sexism, for instance. Her goal for her students is simple: raise their awareness. She wants them to take something they once saw as absolute, like their own gender identity, and approach it instead with wonder.

“If you’ve never felt out of place, if you’ve never felt delegitimized, then you probably have a fair amount of privilege,” she says. “But then think about, ‘OK, what does that mean for me?’ Think of the times when it would be possible for you to just listen. If you can do just that, you’re on your way.”

Continuing with class, Hartelius explained that same-sex friendships typically start out early in life, as 4- and 5-year-olds. I smiled to think about my own daughter, who is 5, and currently identifies as a fiercely independent unicorn-loving princess with an endearing curiosity. When I pick her up at school, she and the other girls in her class are making magical potions in the sandbox, while the boys play racing games with some sort (any sort) of wheeled toy. Hartelius brought up a similar example based on her child’s play during class, and I laughed. “These are real-life examples,” she says, adding that while these patterns have been found in study after study, there are always outliers.

Throughout the lecture, Hartelius worked her way through same-sex friendships at different ages, and arriving at adulthood, shared an anecdote about her husband’s fantasy football leagues, plural, to illustrate that our individual definitions of intimacy and genuine closeness vary widely. In fact, research shows that those definitions may be based on physiological connections in the male and female brains—which means that two people playing video games together can feel as intimately connected as two people having an hours-long conversation.

Then Hartelius played a clip from When Harry Met Sally, where the main characters discuss why men and women can’t possibly be friends. Her TA handed out a worksheet, which I completed with rapt attention, that presented insightful questions about who we consider a best friend. My mind played its own clip, a time lapse through all the best friends I’ve known at different stages of life (most of them female, a detail not lost on me), from slumber parties to dorm rooms, from bridesmaids dresses to divorce papers, from tantrum-taming tactics to cancer diagnoses.

A few students jumped at the chance to share at Hartelius’ request and stirred a lively discussion. Hartelius listened, equal parts therapist and talk-show host, quipping, “sometimes I do feel like Dr. Phil up here.” She carefully extracted lessons as students shared and reflected it back to them. “Yes, the norms of reciprocity.” “Exactly—you had to define the relationship.” “Yep, that’s the burden of labor.”

She makes a point to model what she wants the students to do: listen and try to understand how their personal experiences play into a broader societal discussion. Our conversation shifts from our work toward raising young children. How can we as parents support our children, set an example, and raise citizens who are aware, open, courageous, kind, and vulnerable, when it seems all the cards are stacked against us? How can we as teachers share a message of inclusion and compassion, of strength and grit, knowing it may not land with every student?

“I’d rather yell into the storm than not,” she says.

Illustration by Peter Arkle