Would Separating Teaching From Research Make Universities More Productive?

At the center of the debate in Texas over the future of higher education stands a premise, accepted for generations, that at top universities academic research and teaching are inseparable. In recent months, the UT System regents have probed that idea with the intent of possibly toppling it, relying on the writings of a think tank that advocates separating teaching and research and de-emphasizing the latter—all in the name of productivity.

How sturdy an idea is it? Defenders offer as Exhibit A the double helix, a discovery made decades ago by academic research scientists that, at the time, offered no immediate application and wasn’t immediately taught. Today it represents the foundation of medical science and biomedical engineering and is a staple in any introductory biology class. As Exhibit B they mention quantum mechanics, also a discovery born of academic research, that seemed ethereal at the time. It’s now the basis for cutting-edge physics and computing, and students learn it in any class on electricity and magnetism.

Allow me to offer as Exhibit C this issue of the magazine. Perhaps nowhere is the link between research and teaching clearer than in the field of education. For this issue, we have canvassed researchers across campus to ask them what works in education and what does not. Each of the professors we talked to—experts on literacy, psychometrics, teacher training, physical education, and autism—said their research informs their teaching and contributes real knowledge to the subject.

When we as a state weigh whether to design new standardized tests or eliminate physical education in the name of scoring better on those tests, we should know what the research shows will be effective. And we should want the teachers of future teachers actively examining the data, so they know what skills to impart to their students. That is what will make their teaching more productive.

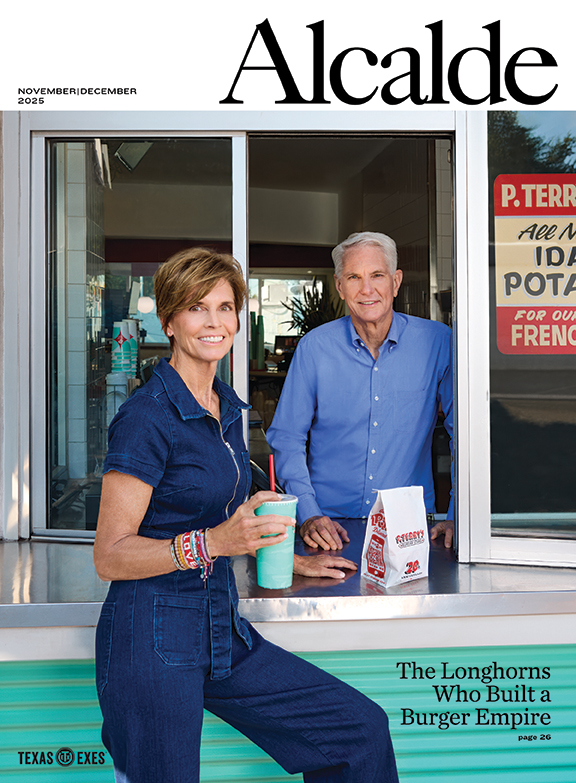

On the cover we say education in Texas is on the brink. UT, in particular, stands on the precipice. A proposal to separate teaching from research, or to value research solely on its immediate applicability, is as misguided as it is shortsighted, and it could thrust Texas into the depths of academic ignominy.

That’s not to say we shouldn’t emphasize good teaching (see p. 30), or that we should glorify tenure-track professors, who do research, over lecturers, who mainly teach. Both are vital to any world-class university. It should be noted that UT is increasingly focused on commercializing its intellectual property as a way to boost revenue. But implementing at Texas a system like Texas A&M’s, which grades professors on how much money they “make” or “lose” the institution, would spell disaster for UT and the Tier 1 status it has worked decades to achieve. And it could lead to our state missing out on the discovery of the next double helix or quantum mechanics.

A great research university is a job-creator, an idea-generator, and a problem-solver, but it is not a business. Trying to make it one would be, quite simply, counter-productive.