The Live Music Campus of the World

Live music and Austin, Texas. An obvious combination, but not by coincidence. Deep in the heart of the Live Music Capital of the world lies the source of the city’s countercultural roots: 40 square acres that have produced and played host to some of history’s greatest performers.

But as The University of Texas sprawled to more than 400 acres, coupled with the city’s rapid growth, the connection between the campus and the community which once burned bright had started to fade away. Not anymore.

When UT President Jay Hartzell, PhD ’98, Life Member, laid out his 10-year strategic plan in the 2022 State of the University Address, one component was an initiative to expand live music experiences at UT. To that end, he formed a live music task force and recently added an Austin mainstay, longtime radio host and writer Andy Langer, BJ ’94, as the school’s first Senior Director of Live Music & Entertainment Experience.

The University has since cranked up its offerings and revitalized campus staples, all with the goal of further integrating into the city’s vibrant music scene. It echoes the past century, wherein concerts served as the catalyst to unite a diverse student population, leading to the popular perception of Austin as the home for live music.

It’s worth remembering how we got here. And it started long before Willie Nelson packed up and fled Nashville for Texas’ capital city.

As the story goes, a gang of renegade musicians forged the outlaw country scene in the 1970s at legendary clubs including Threadgill’s and the Armadillo World Headquarters. A public television show called Austin City Limits brought them to the world, and the rest is history, right? Well, not entirely.

Decades before redneck rock and progressive country made Austin internationally renowned, the city’s premier institution was carefully crafting musical diversions for generations of stressed-out students.

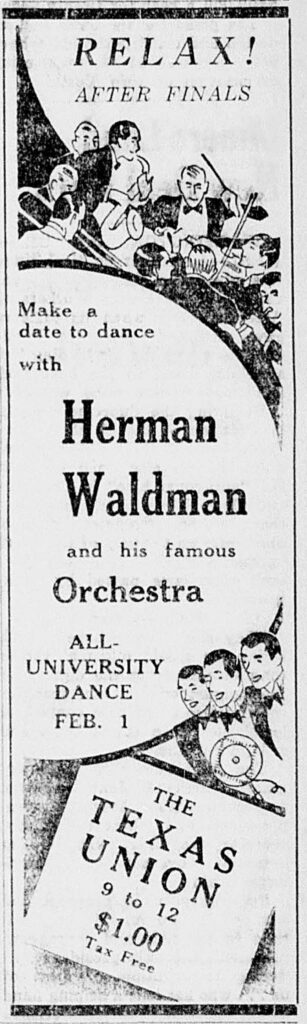

It began with the All-University Dances—social gatherings held downtown as early as 1901 and put on by a collection of fraternities called the German Club. Once their popularity proved overwhelming, the Board of Regents dissolved the club in 1929, and the University began administering the events, first in UT’s North Hall, the now-long-gone women’s athletics gym also known as “the shack” (a nickname that described many of the buildings on campus at the time).

Gregory Gym soon opened in 1930, providing the school’s first modern venue, with wide-open wooden floors that were ideal for cutting a rug. However, namesake Thomas Watt Gregory, LLB 1885, felt the greatest need was for a “nerve center around which all student, ex-student, and faculty activities should revolve.” In 1933, that vision became a reality with the opening of the Texas Student Union.

Exactly 50 years into its existence, the University had its first official student center. Unofficially, it was the “living room” of the student body, where music was central to everyday life. The Union offered dance classes and provided pianos, phonographs, and a record library.

Even through the Great Depression, the University kept humming, thanks in large to the discovery of oil on UT-owned land in West Texas. The school’s first auditorium, Hogg Memorial, opened alongside the Union, and by 1936, the front page of The Brownsville Herald declared, “Oil Transforms University of Texas Into the Show Place of the Lone Star State.”

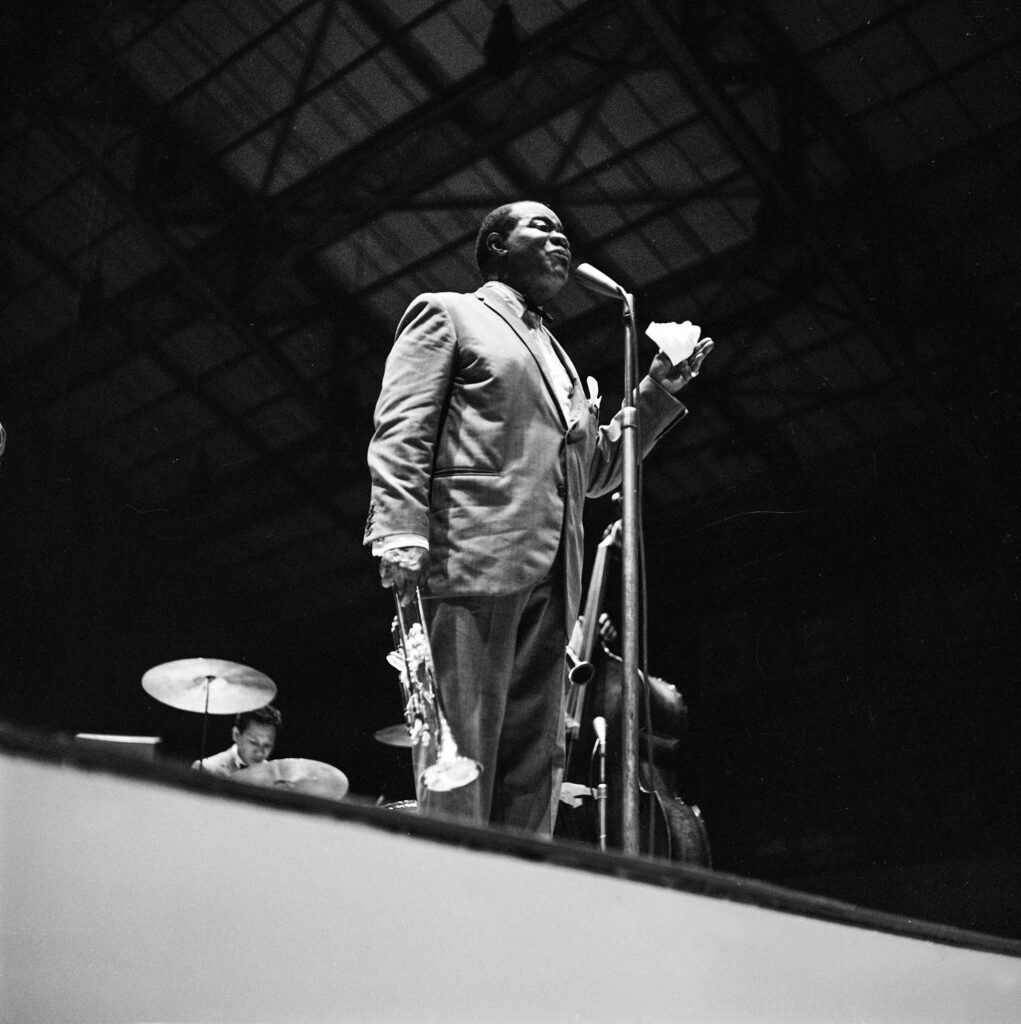

At the height of the Swing Era, UT’s burgeoning prominence drew touring orchestras that included bandleaders such as Bennie Goodman, Louie Armstrong, and Duke Ellington. Despite its small size, Austin became a major hub for Big Band music, while the lines began to blur between so-called art music and dance music.

“Since the late 19th century, Americans had seen popular music as the opposite of art music,” writes Michael Schmidt, BA ’03, PhD ’14, in a digital history project he co-created titled “Local Memory: A Musical History of Austin.” “How audiences enjoyed pop music played a key role in its lowly status. People danced to it or were impressed by its weirdness and novelty. Concert music, on the other hand, was listened to attentively by a seated group of connoisseurs.”

By the early 1940s, UT had become one of the biggest venues for dance orchestras in the country. Although the fun slowed during World War II, new sounds soon emerged. “Postwar dance venues featured new-fashioned styles of pop music, prompting the formation of a slew of new bands in town, while attracting musicians from surrounding small towns,” Schmidt writes.

Clubs began proliferating around Austin. Honky tonks lined South Congress Avenue. Juke joints on the East side showcased rhythm and blues. A converted airplane hangar called City Coliseum opened in 1949, followed by the Municipal Auditorium in 1959, each drawing acts that included Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan. Threadgill’s had obtained the county’s first beer license following Prohibition and paid local musicians with two rounds of free drinks. The city’s musical identity was coming into focus.

Back on campus, the Waller Creek Boys could be found at weekly “folk sings” in the Union’s Chuck Wagon restaurant, featuring a frosh Janis Joplin, who faced ridicule and left for San Francisco after a single, difficult semester in 1962. (She returned as a conquering hero to play the Union Ballroom, Gregory Gym, and one final time in 1970 in front of a reported 5,000 fans at Threadgill’s.)

Thanks to a 1960 expansion, the Texas Union had nearly doubled in size. “Flush for the first time with space and cash, the Union hit its programming stride,” according to a 2008 Alcalde article. “At the same time, the ’60s brought an era of political activism never before seen on campus, and the Union became the hub for political protest.”

This period of strife would also grow to define Austin—an oasis where beatniks mixed with hippies and cowboys to create the city’s iconic counterculture.

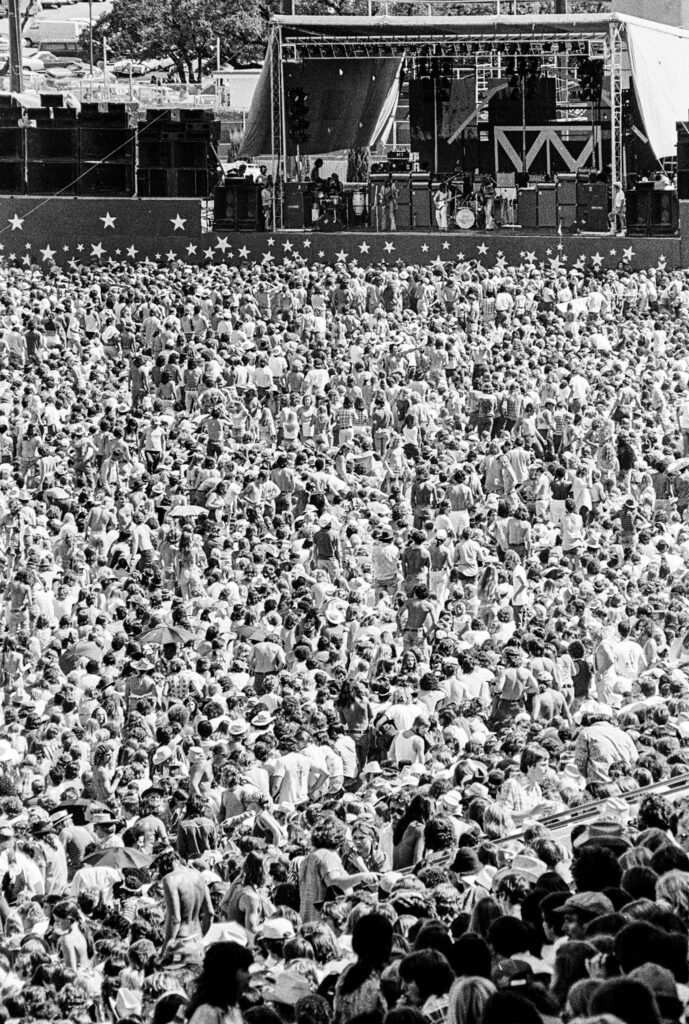

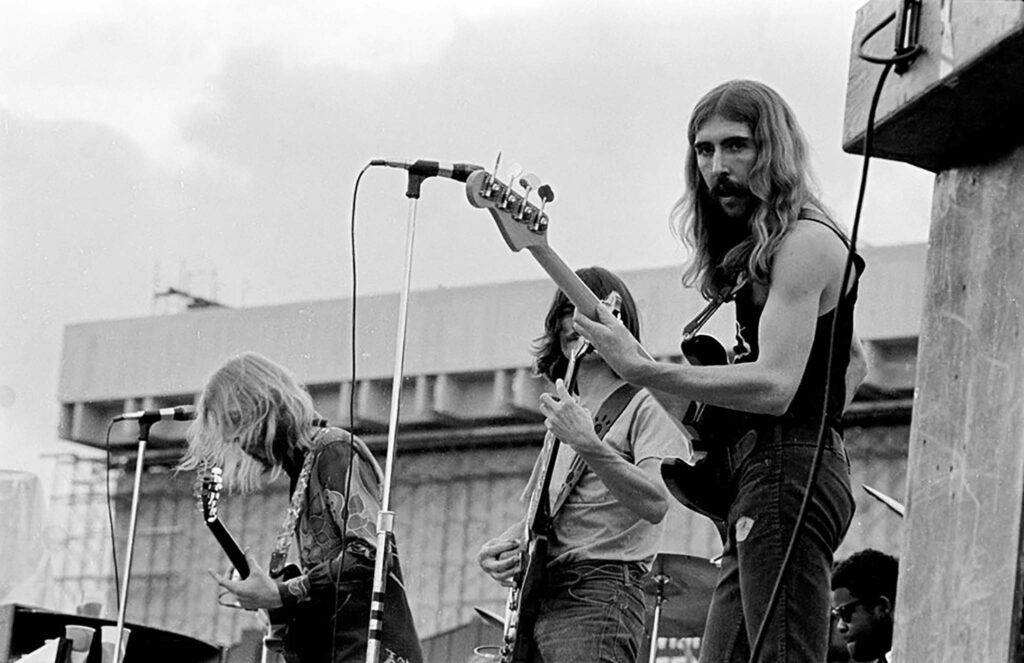

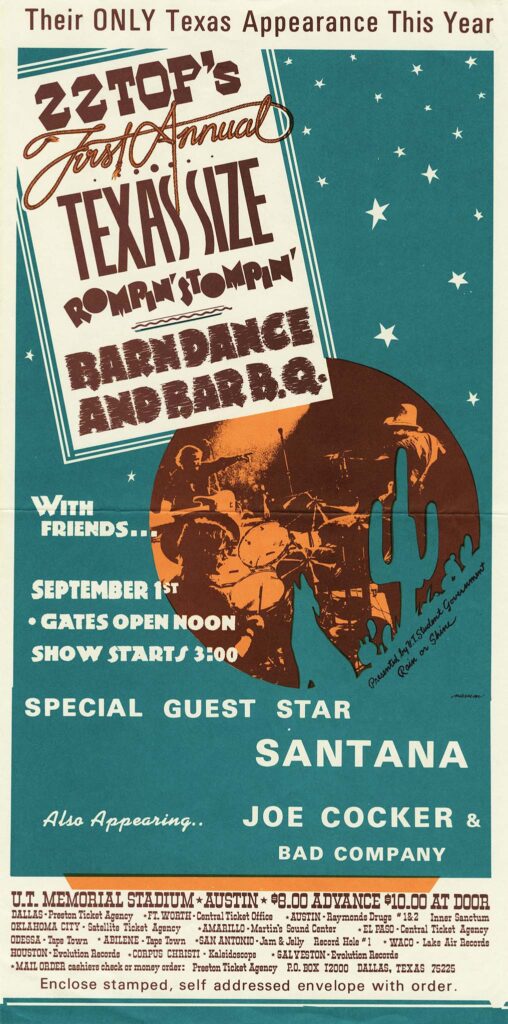

The United States withdrew from Vietnam in 1973, and the following year, the campus saw its most raucous live event ever: the Texas Size Rompin’ Stompin’ Barn Dance and BBQ, headlined by ZZ Top. Typically the domain of the champion football team, Texas Memorial Stadium played host to this “first annual” (and last annual) event. Years of potential future shows were ruined, along with the field, as the drunken crowd ripped up souvenirs of the new artificial turf. Coach Darrell K Royal, Life Member, said never again.

Roughly one month later, on the other side of campus, cosmic cowboy Willie Nelson stepped onto the sixth floor of the Communication Building to record the pilot episode of Austin City Limits. Broadcasting from the 320-seat Studio 6A over the next 35 years, the show would help cement the city as the “Live Music Capital of the World”—a heavily debated moniker dreamed up by the City Council in 1991.

“You talk about the real connection between the University, the music scene, and a major factor in what put the music scene on the map. That’s a direct triangle with the University, Austin City Limits, and the rest of the world,” Langer says. Students lined up for free tickets to see artists that would range from Johnny Cash to Stevie Ray Vaughan to Coldplay. Even Coach Royal was a fan (and a friend of Willie) who was often in attendance.

With the show’s legendary status still years away, new campus venues started to appear. The Frank Erwin Center opened in 1977, bringing major acts like Bruce Springsteen, Prince, U2, and Madonna onto the Forty Acres—while siphoning them away from the Municipal Auditorium (renamed the Palmer Auditorium in 1981, it was replaced by the Long Center in 2010).

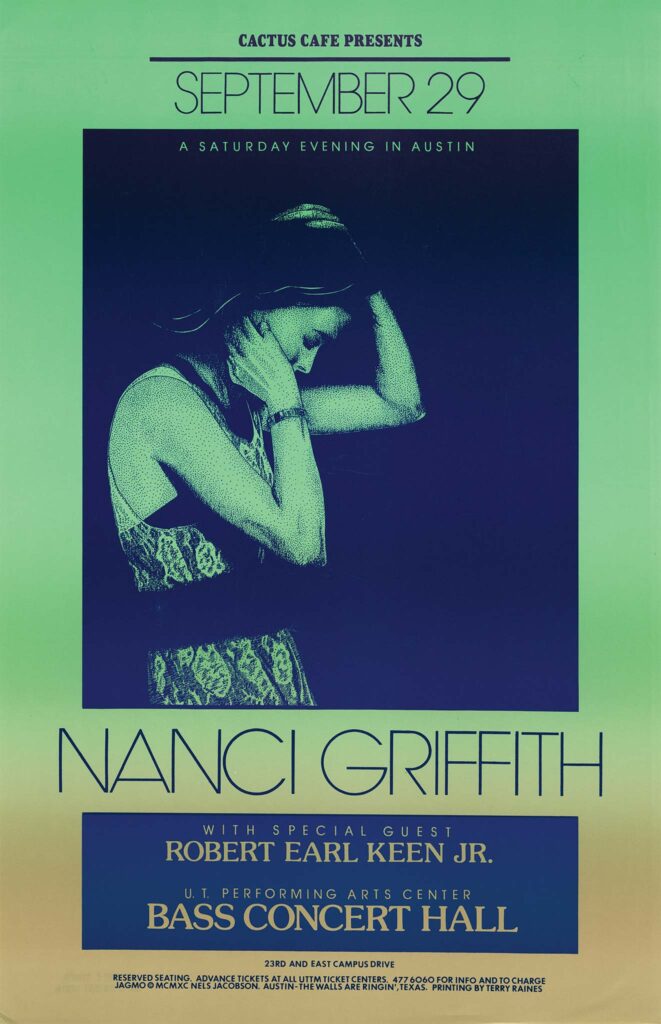

Broadway touring companies and a wealth of classical entertainers were lured in by UT’s Performing Arts Center, a complex of buildings which opened in 1981 and includes Austin’s flagship theatre, the 3,000-seat Bass Concert Hall.

Less highfalutin experiences could still be had back at the Student Union, where the Chuck Wagon had transformed into the Cactus Cafe, an intimate setting for folk icons such as Guy Clark and Nanci Griffith, as well as Townes Van Zandt, who performed more than 100 times at the eclectic coffeehouse.

“It brought a lot of people onto campus,” Langer says of the Cactus. “There is not another small listening room for singer-songwriters, for jazz, for the edge of the alternative country movement. The town’s best listening room is still sitting right here.”

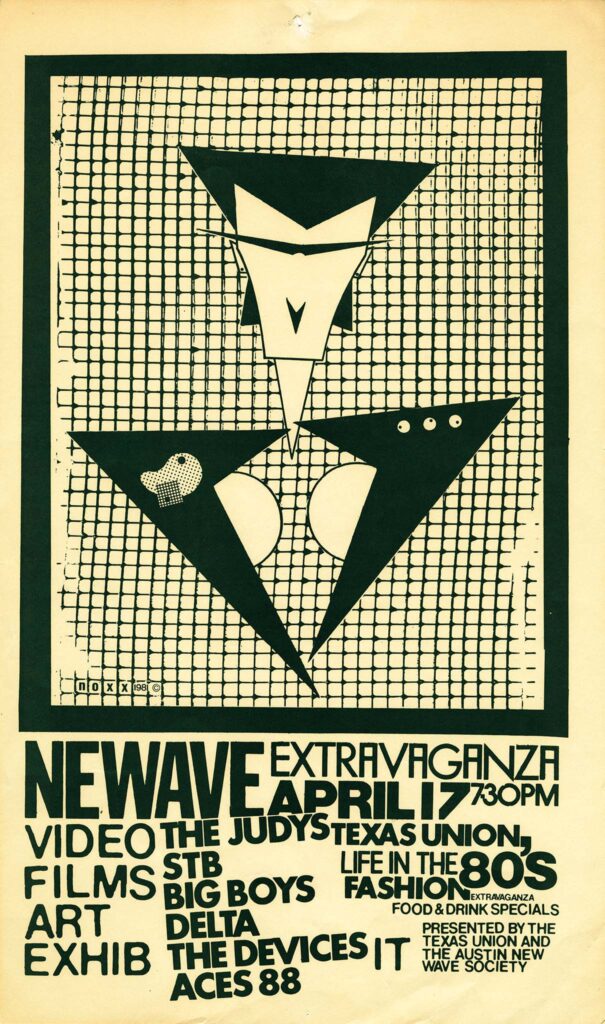

The adjacent Texas Tavern catered to shows too loud for the Cactus, as the punk rock and new wave scenes exploded into the ’80s, spilling over to the Drag (or Guadalupe Street, for the uninitiated) in spots including Raul’s Club and Hole in the Wall.

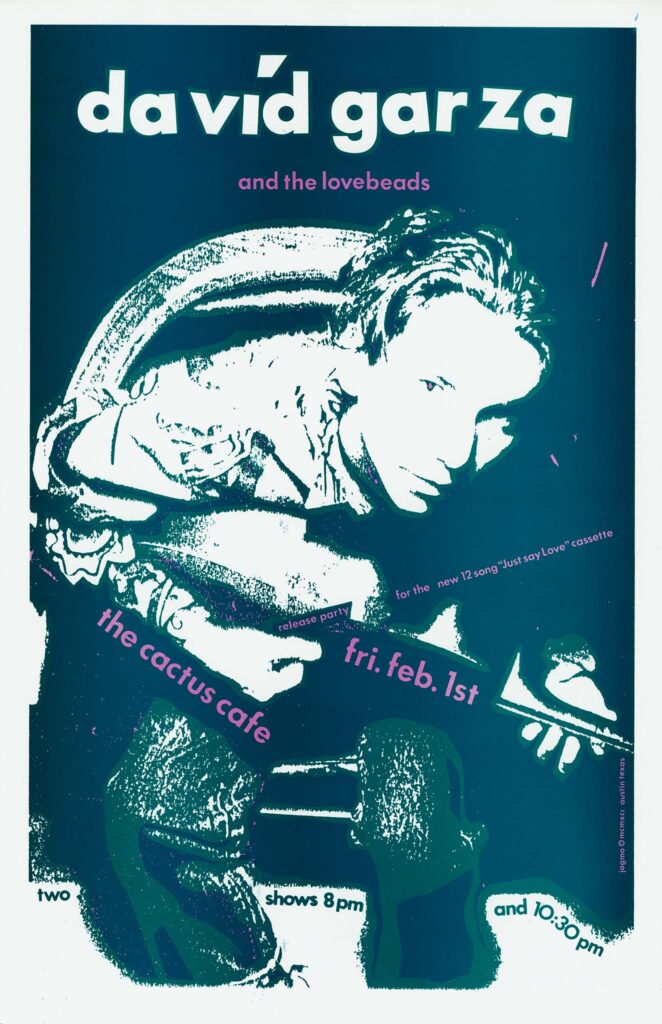

Combined with lucrative fraternity and sorority parties, the campus circuit was a viable home base for touring acts and local bands alike, a fertile proving ground that broke students-turned-stars like Spoon’s Britt Daniel, BS ’93, or producer Davíd Garza, ’90, whose acoustic, three-piece Twang Twang Shock-A-Boom drew hundreds of fans to impromptu gigs on the West Mall, then sold out local haunts like Liberty Lunch.

Around this time, a trio of former UT students formed the now-ubiquitous South By Southwest music festival in 1987. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

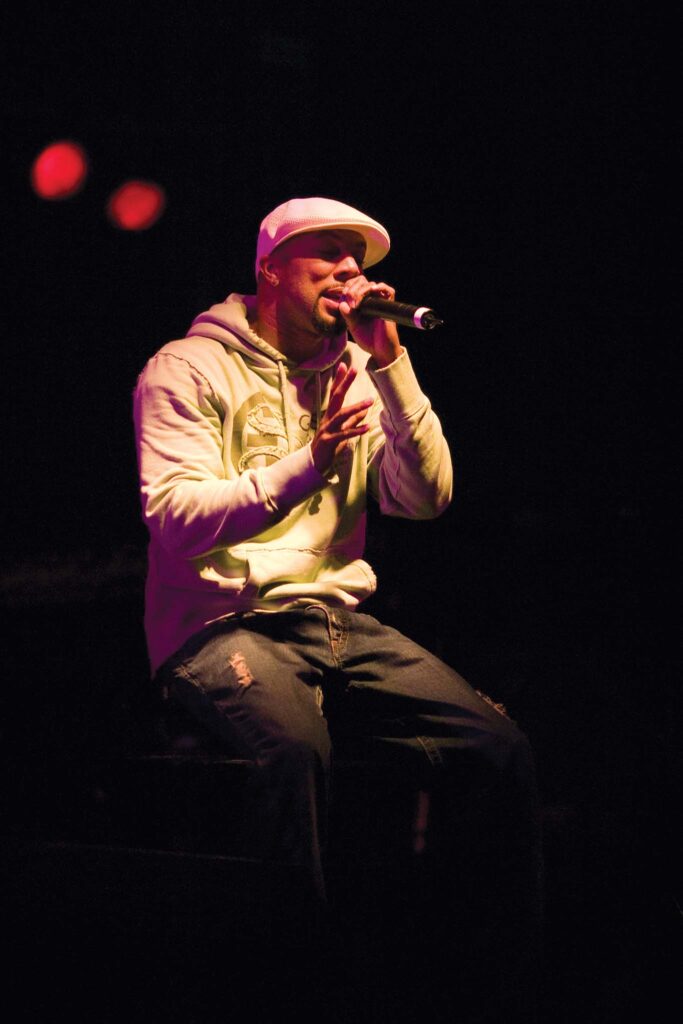

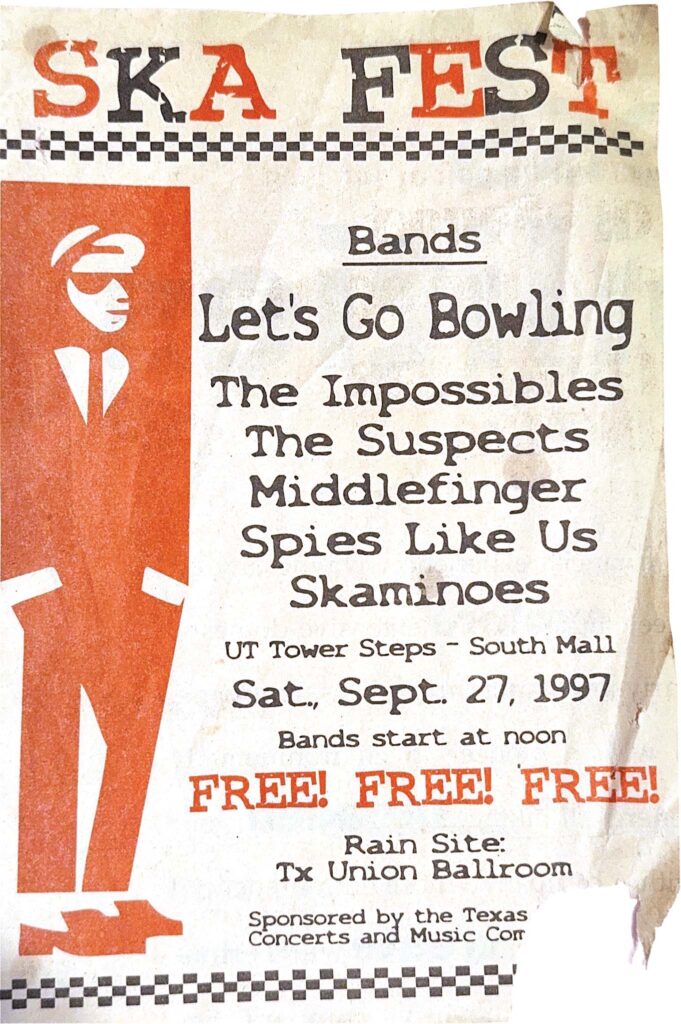

Following a 20-year, ZZ Top–induced hiatus, outdoor concerts returned by way of the Forty Acres Fest in 1993, a free event created explicitly to “foster greater institutional integration.” Booked by the student-led Campus Events and Entertainment organization, it has since brought three decades worth of headliners to perform at the Tower steps, and shows no signs of slowing down.

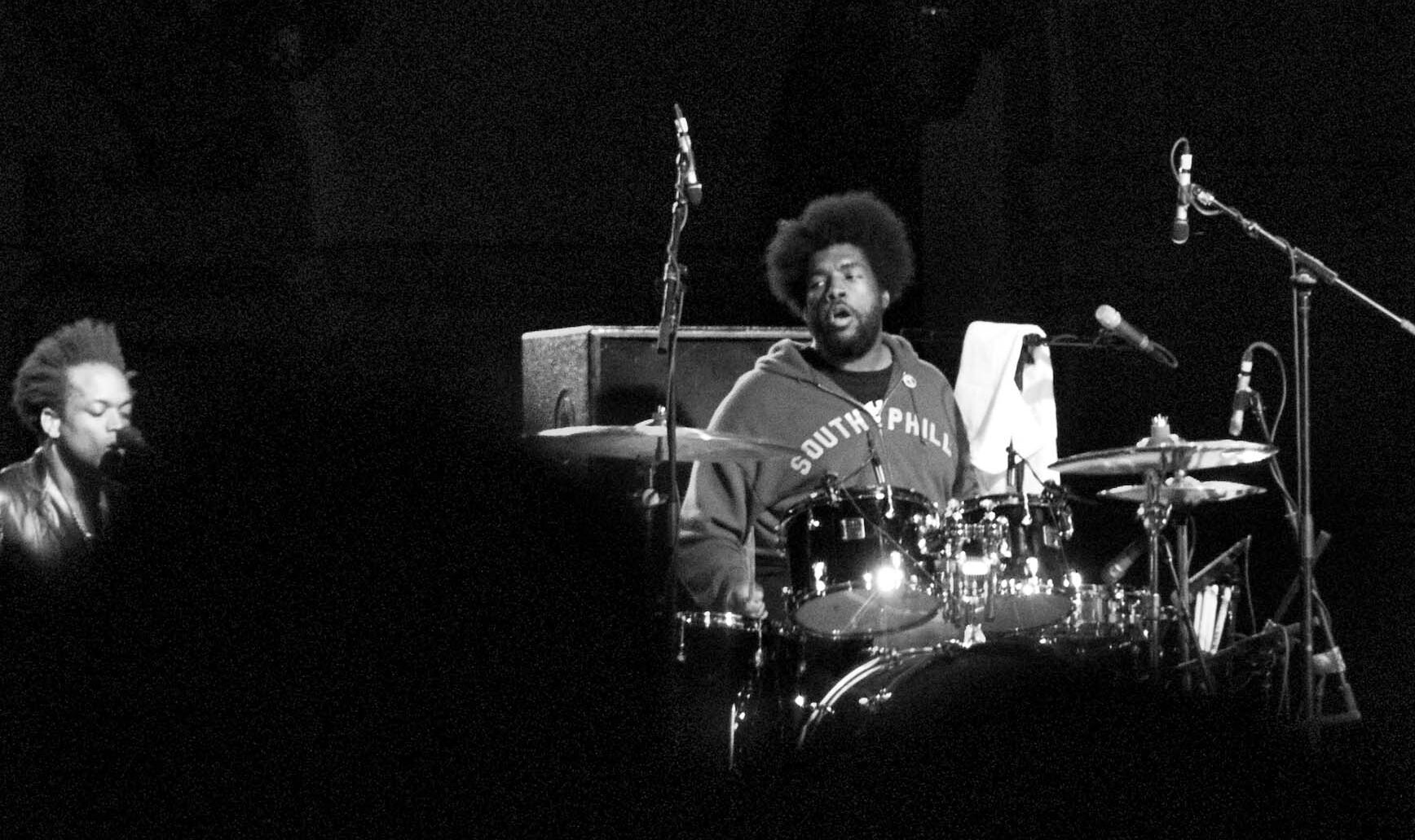

Live music has even returned to the football stadium … almost. Starting in 2018, Texas Athletics has thrown free concerts next door on the LBJ Library lawn to accompany every home football game. Appropriately titled Longhorn City Limits, it has showcased a mix of homegrown talent, starting with Jimmie Vaughn to Shakey Graves, Ghostland Observatory, and Briscoe, as well as nostalgic favorites spanning from Third Eye Blind to Salt-N-Pepa.

“It really was more a question of, ‘Why are we not doing this to the level that we should be?’” says Charles Branch, BBA ’07, Life Member, who is Assistant Athletics Director of Marketing and the creative visionary behind Longhorn City Limits. “Part of the goal is how can we engage with the community, beyond just here on campus. It’s really a space for all Texas fans, whether you’re a current student, an alumnus, or a visiting fan.”

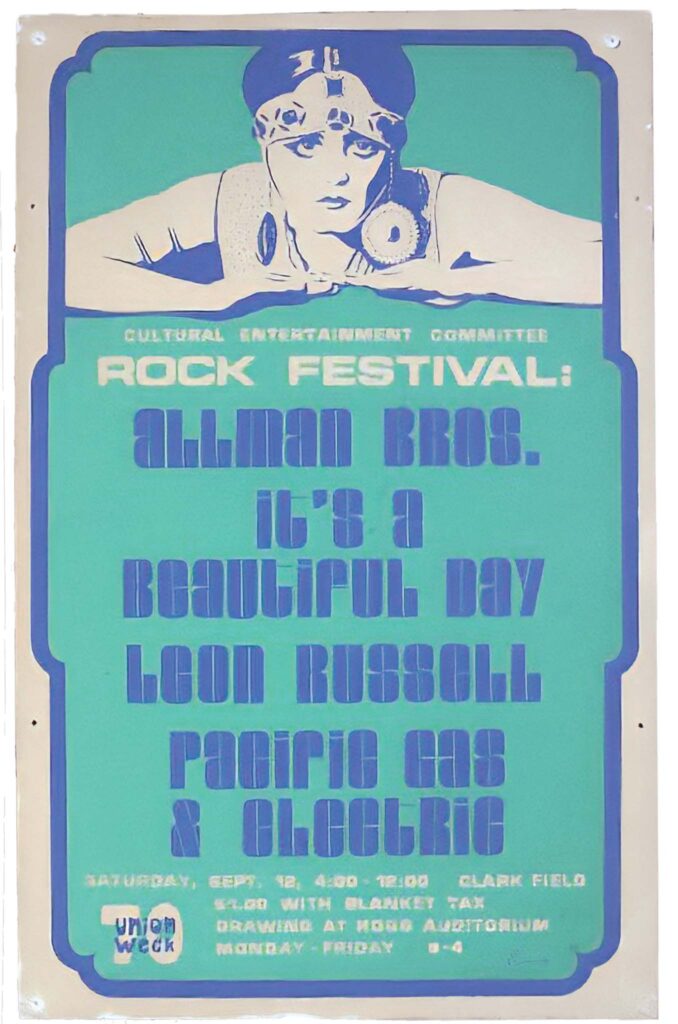

In a city defined by change, its connection to live music has remained constant, whether it’s the Allman Brothers rocking Clark Field in the ’70s or Gary Clark Jr. reopening the renovated Hogg Auditorium in 2023.

Which brings us to today, where the University is still crafting new experiences, with a renewed imperative to bring live music to the students and bridge the gap between the community and the campus.

Recent creations include the inaugural Texas Songwriter in Residence in 2023, a program which brought Cactus Cafe–veteran Darden Smith, BA ’85, back to school and placed him in a variety of settings. To provide students a respite heading into finals, the Ball in the Mall launched in 2023, with Diplo performing in front of the Tower. The new Hook ’Em House took over Antone’s during SXSW 2024 and featured Sloan Struble, ’19, known professionally as Dayglow.

“This isn’t stuff we’re going to make money on. This isn’t stuff that there’s a lot of hidden motives behind,” Langer says. “It’s giving students ways to interact with arts and entertainment and culture. And all of it has the dual purpose of strengthening the connection between what happens in Austin and the Forty Acres, while creating memories for students.”

That spirit can be found in smaller, more off-the-radar events, such as the engaging and educational Second Saturdays at the Blanton Museum. It is reflected in the Butler School’s Musical Lives, an outreach program that provides children in underserved communities with high-quality musical experiences.

“I think you’re going to continue to see live music in some more nontraditional ways on campus. And maybe in places you typically didn’t see them earlier,” Branch says. “You’re slowly seeing more and more live music on campus, which is something that differentiates UT Austin from pretty much every other college out there.”

CREDITS: From top, Briscoe Center for American History (2); Alcalde archive; Briscoe Center for American History; Austin Museum of Popular Culture; Briscoe Center for American History; from left, Benjamin Ho (2), Don Mason; Texas Athletics; UT Division of Student Affairs; from left, Texas Athletics, UT Division of Student Affairs; band posters from Briscoe Center for American History (6); newspaper clippings courtesy of The Daily Texan (2); Ska Fest flyer courtesy of Ryan Parker

Want to see more? Watch the accompanying Alcalde doc here:

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.