Good Reads Q&A: A Longhorn Uncovers Family History Across Continents and Generations

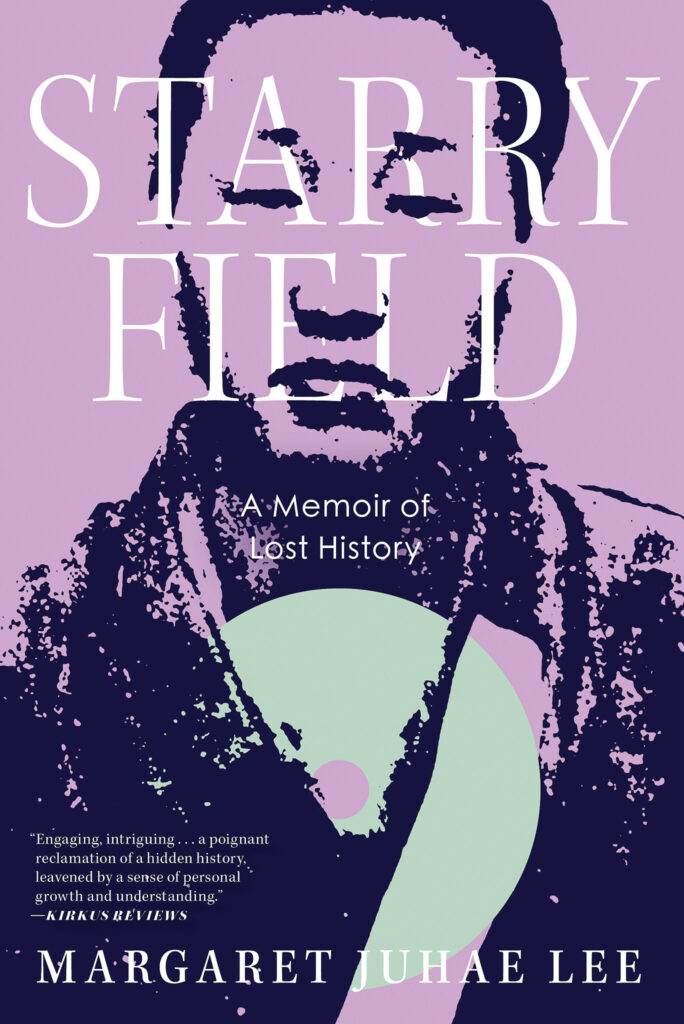

From starting at UT as a pre-med Plan II student to a graduate degree in the art history department, to a master’s in Cultural Reporting & Criticism at NYU, Margaret Juhae Lee’s career has taken her all over the country—and the world. Her debut memoir, Starry Field, combines investigative journalism, oral history, and archival research to tell the once-lost story of her family’s life in Korea. The Alcalde spoke with Lee, BA ’88, MA ’92, about her myriad influences and the reverberations of this personal odyssey.

Could you take us through your decades-long writing process?

This is definitely a family project. I began helping my father, who was a professor at UT’s School of Public Health, research his father while on sabbatical in Korea. My grandfather died when my father was a baby, so the only thing that he knew about him was that he was put in prison by the Japanese and died. My father grew up thinking he was the son of a criminal. My grandmother never talked about her husband. He was just this hole in our family history.

I grew up not knowing who my grandfather was … but also not knowing much about Korean history because it was too painful for my parents, I think. But when my father started delving into his father’s life, he discovered right away that my grandfather was the leader of the student movement [protesting Japanese colonization] in his hometown. My father had gone to talk to a former classmate of his who was a professor of history in Korea, and this friend recognized my grandfather’s name right away. He said, “Oh, he’s in history books.” And we had no idea. It was just this huge revelation.

The research started with my father, then coincided with my going to journalism school. He got ill, and part of his recovery was my helping him with this project. He would send me these notes on family history every week, and then I’d ask him more questions. The search for lost history also became my search because it was something I didn’t grow up with.

I realized that this was the story of a lifetime as a journalist, but it was also my family’s story. I decided that I wanted to go to Korea to try to find my grandfather’s prison and interrogation records, the copies of which my grandmother had burned during the war because she knew that they were dangerous. So a big part of my book is almost like a detective story.

How did you find your way to this hybrid of genres and forms?

I interviewed my grandmother while I was in Korea, and she had never talked about her life at all … She had to survive, and the way she could survive was to not deal with the past and just move forward. I did these three long, oral history interviews with her, and now they form the structure of the book.

Early on, before I even went to Korea, I thought this was a book of investigative journalism—because that’s what I knew how to do. I wrote some chapters, but it didn’t feel quite right. I knew then that I had to insert myself into the story as a character, and, frankly, I didn’t know how to do it because I didn’t have the practice. So I needed to put it away for a little bit and figure out how I would write it. It’s almost harder to write memoir than fiction, because you can’t make things up … But my models were novels, not nonfiction, in terms of structure and narrative arc and using dialogue and thinking of these people in my family as characters, too.

It also took me a lot of time to realize why I was doing it. Initially, it was to understand my father. It wasn’t until I had a family of my own that I realized I was writing this for the next generation, so they would grow up knowing their history, because I didn’t have that privilege. I grew up in Texas in the ’70s without many Asian people around and was always treated like a foreigner. I went to UT in the mid-’80s, and there wasn’t an Asian Studies department yet. I didn’t come into that [Asian American] identity until I was an adult, and I don’t want my kids to feel so unmoored.

What was the hardest part of writing the book? The most rewarding part?

I think the hardest thing was feeling the weight of history. When I started this book, there was no concept of “intergenerational trauma.” That was not even a phrase. My grandfather was willfully forgotten. He was tortured in prison by the Japanese. The trauma of war—all of it. I think that was the hardest part—and realizing, too, that I couldn’t rush through this. There was a psychological toll. I had to really process and sit with things. And that, too, is why it took so long.

But when my father made these discoveries about his own father, I saw a transformation of a person. My father was a very quiet man, very stern; he rarely smiled. Korea is a very patriarchal culture, so when you don’t have a father, there’s a lot of stigma to that. When we found out about my grandfather, it was like a weight was lifted from him … I remember my mom saying, “Oh my god, your father talks so much now! He won’t shut up!” But I think that was probably his true personality as a child, and it had just gotten muffled his whole life. I feel like I got to know my real father.

Because it’s such a personal project, how do you envision readers relating to this story?

My hope is that people will think about exploring their own family history—and realize that, when you don’t confront parts of history, there’s an absence there that is also passed down. In America, we don’t look toward the past very often, but our elders have so much to give us. I think that’s something that’s universal.

CREDIT: Courtesy of Margaret Juhae Lee

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.