How the Texas Longhorn Became a Living Legend

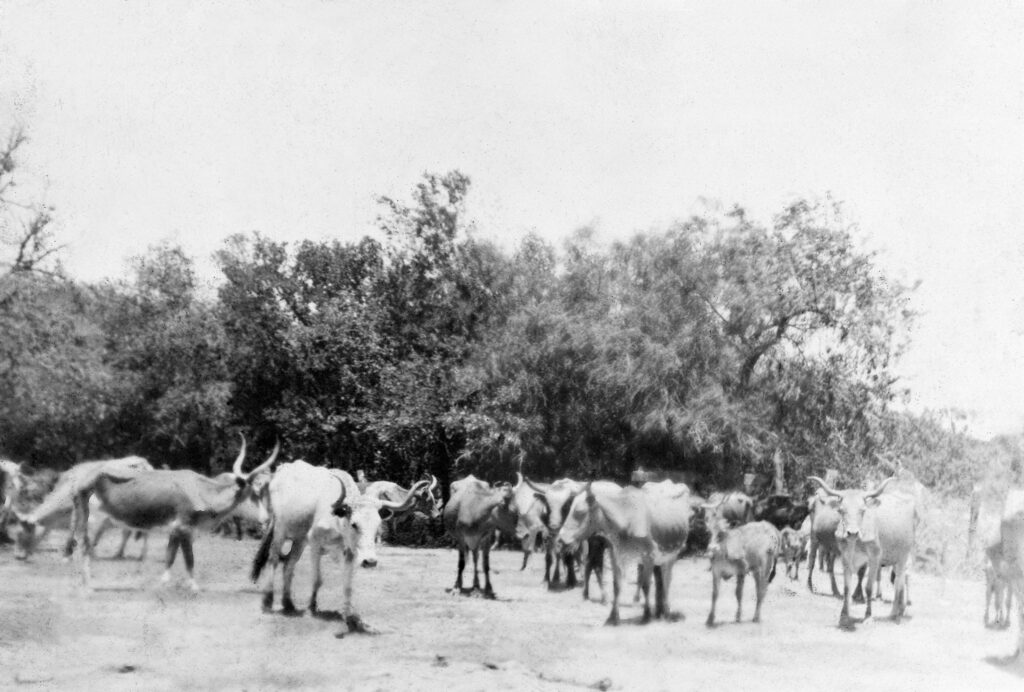

Roaming the brushy expanse of the Texas plains, a herd of Texas longhorns graze under the blaring sun, their sprawling horns casting long shadows on the dusty ground. The sight of one evokes images of cowboys and cattle drives, of vast prairies and untamed wilderness. These iconic cattle are more than just livestock; they are living relics of the Lone Star State’s storied past and enduring character.

Yet, even as they are represented as indelible cultural touchstones in art, literature, and, yes, at college football games, the unlikely story of how the longhorn came to epitomize Texas’s identity is largely unknown and often misunderstood.

After Christopher Columbus unwittingly landed in the Americas in 1492, he returned a year later with more than 1,000 men to establish permanent colonies and convert the Indigenous people to Christianity. Columbus also introduced a handful of European domesticated animals to the island of Hispaniola, including cattle native to the Iberian Peninsula.

These Spanish livestock were eventually imported to Mexico by the conquistador Gregorio de Villalobos in 1521, and in subsequent years, Spanish explorers continued bringing in cattle as missions and settlements were established. “Some stories talk about expeditions dropping off a bull and 10 cows at every creek or river crossing that they came to,” says Will Cradduck, herd manager for the Official State of Texas Longhorn Herd.

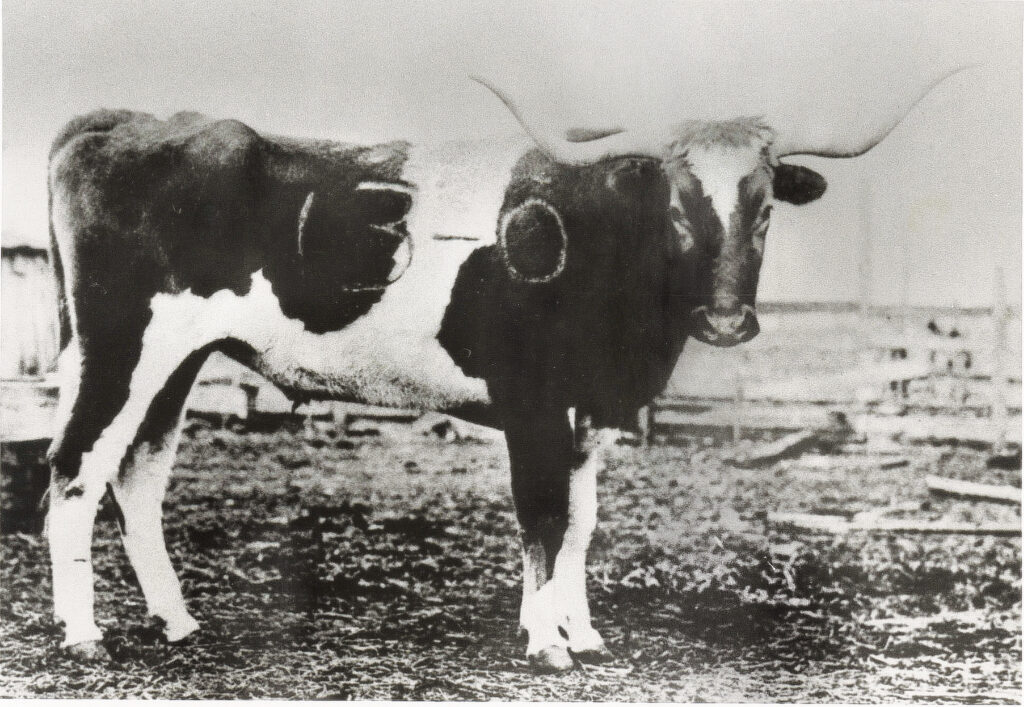

But not all Spanish missions were successful. Whenever a settlement failed, colonists packed up and went back home. However, before abandoning their posts, they turned the cattle loose onto the open land. Over the next few hundred years, the cattle populated with very little human interference, spreading across Mexico, southward into Central and South America, and northward into Texas. Their remarkable adaptability to this region is partly owed to the area’s weather, since they came from similar dry, hot summers and mild winters in Spain and Portugal. In addition, they reproduced quickly and proved skillful at fending off predators with their horns. Slowly but surely, through natural selection, a distinctive breed that would eventually be known as the Texas longhorn emerged.

By the 1860s, longhorns roamed the Texas landscape by the millions. They would end up rescuing Texas from an economy in shambles after the Civil War. When Confederate soldiers returned home from battle without jobs and little prospects for work, they began rounding up longhorns and forming their own ranches. However, the beginning of the modern ranching industry was almost doomed before it started.

“There were wild cattle everywhere. So why would you want to buy one?” Cradduck says. “If you wanted beef, you could go shoot a big longhorn and have beef for your friends and family and neighbors for a couple of weeks or longer.”

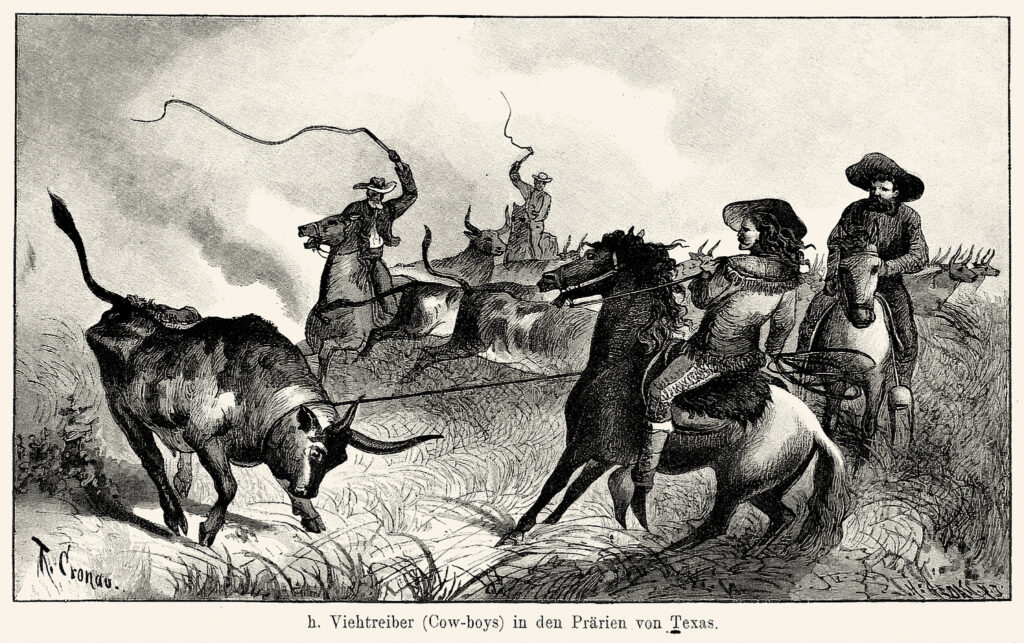

At the time, rail lines mostly ran east to west through Chicago, but unlike other commodities, the longhorn had a trick that other goods couldn’t perform: They could walk. Early ranchers decided to expand into markets further from home, giving birth to the legendary cattle drive.

The first cattle drives toward coastal areas from interior Texas and Mexico were a mild success. Though some money was made, no one got rich. So ranchers set their sights on Abilene, Kansas, where the railroad could transport their cattle to meat markets in Chicago and other major cities in the east, such as New York and Boston, where beef was scarce. A fully matured longhorn worth between $5–$10 in Texas would sell for as much as $30–$40 in Kansas.

Ranchers gathered up larger and larger herds, and with the help of a few dozen cowboys, transported as many as 1,500 to 2,000 or more head of cattle at once. “Without the longhorns, without the early trail drives and the early ranching, we probably would have never had the Texas cowboy,” Cradduck says. Over the next 30 years, ranchers moved somewhere between 20 million to 30 million head of cattle, which is the largest movement of animals under the control of man in the history of the world.

Cattle drives brought large amounts of money back to Texas. With this infusion of capital, they expanded their operations and bought neighboring land and ranches. They also invested in their communities, building churches and schools throughout West Texas. “A lot of people regard the longhorn as the first oil of Texas,” Cradduck says. “It was a big influx of cash into the state when a lot of the other southern states just didn’t have that capacity.”

It was during this time that longhorns became synonymous with the frontier spirit of Texas—embodying traits such as strength, independence, and a fierce determination to survive against all odds. Their toughness on the trail became an advantageous characteristic. “They adapted to having really long, lean legs so they could travel great distances,” says Debbie Davis, treasurer of the Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation of the “original” Texas longhorn. “They don’t have a bunch of loose skin that hangs down to get caught up in thorny brush.”

Compared to other cattle breeds, the Texas longhorn thrived under the harsh conditions and were more capable of surviving the treacherous journey. Not only did they display a higher resistance to drought than other cattle, but they were extraordinarily resourceful in what they ate, foraging available grass, weeds, cactus—thorns and all—and even plants that are toxic or inedible to other animals.

In the late 1870s, a new type of cheap steel fencing wire with sharp points became commercially available. Barbed wire was a revolutionary technology and the first of several contributing factors that spelled the demise of the cattle drive. Within a decade, hundreds of miles of “the devil’s rope” stretched across Texas, fencing off the open range and officially taming the Wild West.

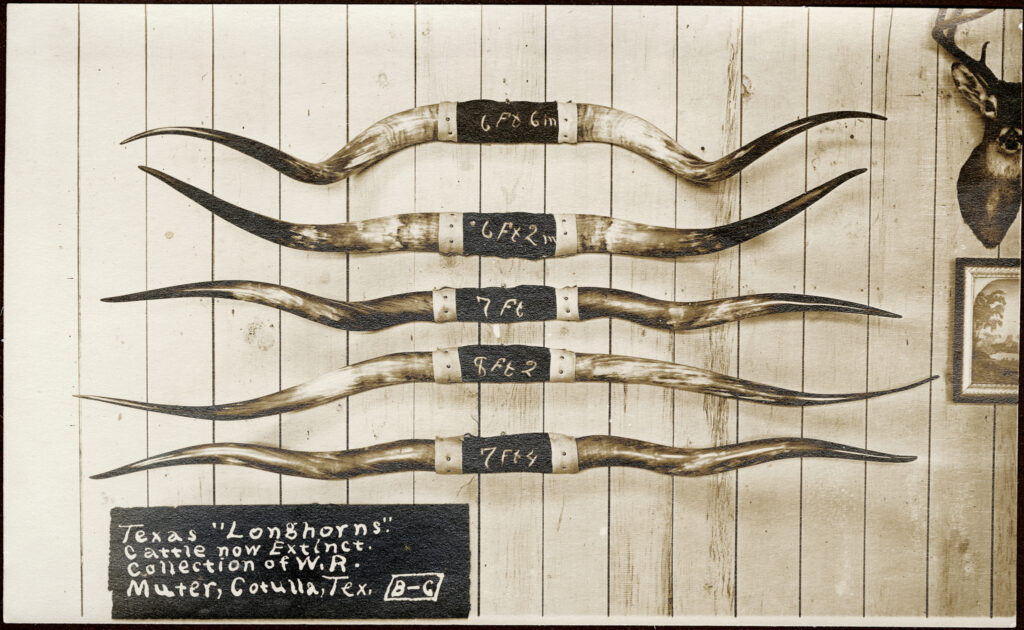

In addition, rail lines continued to grow, and ranchers no longer had a need for the hardy longhorn, whose meat was leaner than English cattle and whose horns made it difficult to pack tightly into rail cars. As it became more lucrative to raise cattle to meet the demands of the changing market, ranchers started breeding longhorns with shorthorn Durhams and Herefords, which produced beefier cattle. By the 1920s, the Texas longhorn was very nearly bred out of existence.

In a cruel irony to any burnt-orange-blooded reader of this publication, it was Oklahoma that first saved the Texas longhorn from extinction. A group of passionate U.S. Forest Rangers lobbied the United States government to preserve the purebred longhorn, and in 1927, Congress appropriated $3,000 to round up the last remaining longhorn cattle and establish a national herd at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge located across the Red River in the Sooner State.

However, perhaps no one has done more for the advancement of the Texas longhorn than famed author and noted University of Texas faculty member J. Frank Dobie. His writings, particularly the book The Longhorns, showcase the rich history and significance of the Texas longhorn in the state’s heritage through vivid storytelling and meticulous research. Many consider it to be the Bible of the Texas longhorn. But his passion for the longhorn extended beyond his literary contributions.

Dobie saw firsthand the end of the cattle drives, and he became a prominent advocate for the preservation of his beloved bovine. In 1938, Dobie spearheaded an effort to secure an official herd of purebred longhorns for the state of Texas. With the help of Fort Worth businessman Sid Richardson and rancher Graves Peeler, Dobie acquired a herd of longhorns and donated them to the State Parks Department, now Texas Parks & Wildlife. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Dobie the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civil honor, for “[recapturing] the treasure of our rich regional heritage in the Southwest from the conquistadors to the cowboys.” Four days later, Dobie passed away, and his funeral was held in Hogg Auditorium on the Forty Acres.

The 61st Texas Legislature officially recognized the State of Texas Longhorn Herd in 1969. Since then, it has honored Dobie’s original intent and strived to keep the cattle as historically correct as possible. Today, with a herd of approximately 250 cattle, the Official State of Texas Longhorn Herd resides primarily at the Fort Griffin State Historic Site and San Angelo State Park. Cradduck oversees the herd where visitors are invited to see the ancestors of the longhorns that roamed Texas more than a hundred years ago.

In the decades after Dobie’s preservation efforts, the nostalgia for the golden age of the Texas longhorn became reflected in popular culture. Western films such as Red River starring John Wayne and Montgomery Clift portrayed a fictional account of the first cattle drive from Texas to Kansas along the Chisholm Trail. In addition, Larry McMurtry further ingrained the romanticization of the longhorn into public consciousness with his sprawling epic Lonesome Dove, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986. Less than a decade later, the Texas Legislature designated the Texas longhorn as the state large mammal.

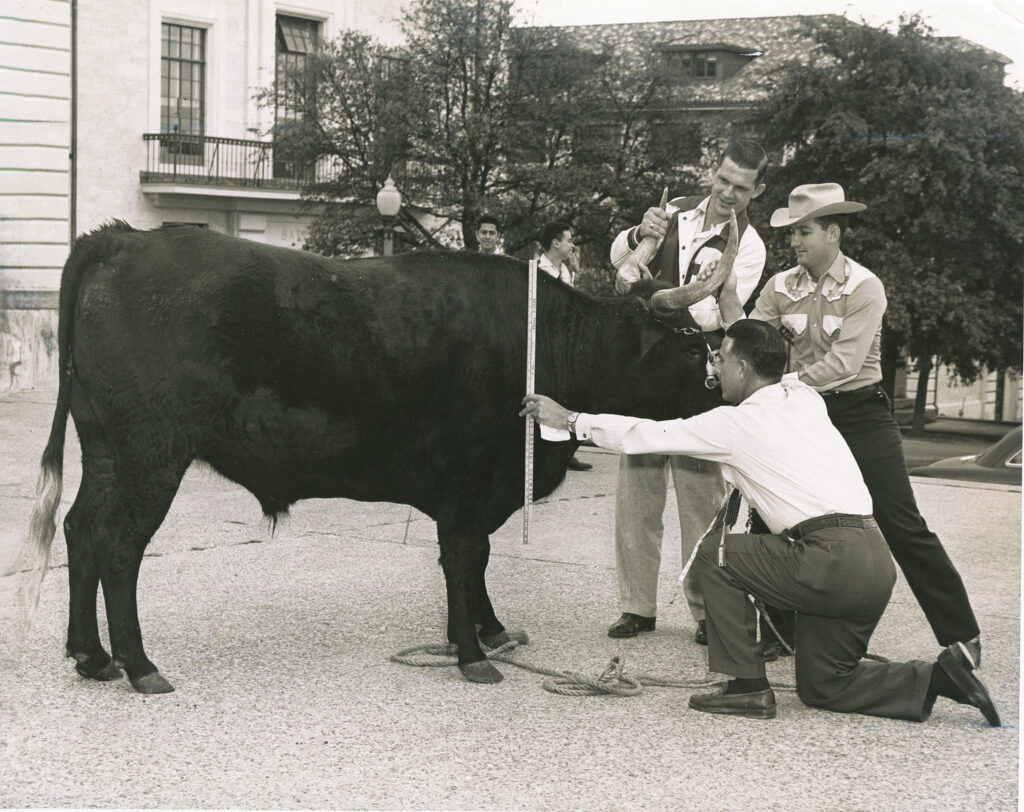

The most famous and beloved Texas longhorn is none other than Bevo. However, the renowned steer was not the original mascot of UT. That honor belongs to a scrappy tan and white American Pit Terrier named Pig. UT alum Stephen Pinckney, LLB 1911, is credited with the idea of using a live longhorn as UT’s mascot. He solicited donations from fellow alumni, and with $124, purchased an orange steer and presented the longhorn during halftime at the Thanksgiving Day football game in 1916. Ben Dyer, then-editor of the Alcalde, reported on this historic university news in the December 1916 issue of the magazine, announcing, “His name is Bevo. Long may he reign!” In time, the new mascot gave rise to the school’s trademark hand gesture and “Hook ’em Horns” chant.

“[Bevo’s] kind of his own celebrity,” says Ricky Brennes, BS ’00, Life Member, executive director of the Silver Spurs Alumni Association, which raises money for the student organization in charge of caring for Bevo during appearances for school events and private functions. “I’d say he’s one of the most photographed animals in the world. Everywhere we go, hundreds of pictures are taken of him. Everybody’s always excited to see him.”

Adopting the longhorn as its mascot would forever tie Texas’ flagship University to the state’s heritage in cattle ranching. As such, ranchers continue to breed and stock them on their land, even though they continue to be less lucrative than other cattle. “People like them for yard art,” says Betty Baker, who, along with her husband John T., owns the current Bevo, as well as the previous two. “People like them because they are UT grads, and they have ranches. [They] just love to look at them because they’re so historic, and they’re so beautiful.”

One such alum is Gay Gaddis, immediate past president of the Texas Exes Board of Directors, who, along with her husband Lee, owns the Double Heart Ranch in the Texas Hill Country. “It’s ironic to me that all these people go, ‘Hook ’em Horns’ and love the Texas Longhorns but don’t know their history,” says Gaddis, BFA ’77, Life Member, Distinguished Alumna, whose family has deep ties to the Texas longhorn. (Gaddis’ mother-in-law, Isabel Maltsberger Gaddis, was a close friend of J. Frank Dobie and co-edited a collection of Dobie’s short stories.) “They don’t know we almost lost them.”

Depending on who you talk to, the Texas longhorn breed is thriving. Formed in 1964, the Texas Longhorn Breeders Association of America is the largest organizing body that governs the registration of Texas longhorns. Rick Fritsche, registrar and office manager of the TLBAA, says they have had an estimated three quarters of a million longhorns in their registry since its inception. By contrast, the Cattlemen’s Texas Longhorn Registry, established in 1991, says there are less than 2,000 registered historic Texas longhorns like the ones Dobie helped preserve. Since this represents less than 1 percent of all registered longhorns, The Livestock Conservancy lists the breed as “Critical” on its conservation priority list.

“[The longhorn] has emotional ties to people from Texas because they identify with this majestic animal as being part of their history,” says Davis, who is among the handful of ranchers possessed with a fiery passion to follow in Dobie’s footsteps and preserve the original historic longhorn. “It is … the icon of our state.”

CREDITS: From top, Texas Historical Commission (2); Getty Images/duncan1890; Roy Wilkinson Aldrich papers, Briscoe Center for American History; Texas Exes archive (3)

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.