The Complete Story of DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium

The first time the stadium felt special to me—this should be obvious, but for transparency’s sake, I mean Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, otherwise referred to as DKR, or, simply, the stadium—was two days after my 33rd birthday, much later than most people have their epiphany inside the ninth-largest of its kind in the world. In fact, almost everyone interviewed for this story and all my friends I’ve asked over the years recalled that the first moment DKR felt special to them was as a cherub clad in orange, not as a married reporter in attendance for work instead of pleasure.

You remember the game, all 102,315 of you who attended Texas’ double overtime victory over Notre Dame on Sept. 4, 2016. It was sticky down on the field that night, summer’s last gasp before summer part two, or, as we northeasterners call it, “autumn.” Normally, I spend home Saturdays in the confines of the Bill Little Media Center, the icy, quiet press box on the eighth floor on the west side of the field. The last five minutes of regulation, however, reporters are allowed to descend upon the turf and watch the game wind down before press conferences begin. In the two seasons prior, my first covering Texas football, the ends of games were generally blowouts in either direction, so catching a backup QB get some reps in wasn’t all that enticing. Some games, I’d even stay up in the press box until the final whistle, just to savor those extra moments of air conditioning.

Not on that night. As the game clock crept down toward five minutes, nobody could wait to get onto the field. Notre Dame was up 35-31, and by the time I made it down there, Texas was driving toward the end zone, eventually taking the lead on a 19-yard D’Onta Foreman touchdown run. It was 3rd and 5, and true freshman Shane Buechele had almost just thrown a backbreaking interception, the kind that sucks all the air out of the stadium. Texas fans knew that feeling, on the heels of two mediocre seasons: they’d come close to taking down giants, only to come up short in big moments. After being overturned on replay, Foreman took the handoff, pinballing off the Irish defensive line and headed toward the ground behind the line to gain. But he masterfully maintained his balance and zipped past the defensive backs into the end zone. The extra point was blocked and returned by Notre Dame, which tied the game at 37.

In college football overtime, the teams start from the same spot each possession, so those of us lucky enough to be on the sideline for this moment—the largest home crowd in Texas history—grabbed a good spot to see the action. I was parked right at the 10-yard-line, almost parallel to Tyrone Swoopes, BS ’16, as he took the snap in shotgun formation. Taking last possession in the second overtime, and only down three points, Texas could win with a touchdown. Swoopes motioned the tight end Andrew Beck, positioned in the backfield, over to the right for an obvious designed run. It didn’t matter if the move was telegraphed, Swoopes was going to score. The senior danced and dove over the plane of the end zone and DKR erupted in ecstasy.

That was the closest I’ve ever come to screaming while a credential hung around my neck. But it wasn’t just the game—the on-field product as it’s called in the biz—that made the hairs on my neck stand at attention. It was the feel of the cushioned turf below my boots; the roar of the burnt orange faithful (and collective gasps); the pulsating energy that can only be felt when you get your buns off the couch and park yourself inside the behemoth of a sporting arena.

This is the story of that sporting arena—where it came from, the people who keep it humming on gameday, and what’s next.

For as long as he has been around the program and for as many hours as he spends inside the stadium, Arthur Johnson doesn’t watch a whole lot of football live. Neither does his team, the 50ish-strong unit of football operations staffers who live—sometimes literally, at least for a day or two at a time—inside DKR. As associate athletics director for football operations, Johnson oversees facility operations of the stadium on gamedays, and as such, spends the 15 or so hours he’s on campus during home Saturdays doing everything except actually watching the game.

For a 7 p.m. kickoff, like the 2018 home opener against Tulsa on Sept. 8, Johnson gets in between 4:30 and 6 a.m. He’ll grab some breakfast, take meetings, and walk the stadium steps, all the while dictating voice-to-text memos into his phone for anything he can remember during his contemplative stroll. He might dip back home to enjoy lunch with his wife T’Leatha and son, Aaron, but then he’s right back at the stadium, walking steps, popping his head into the press box, shaking hands in a few suites, stopping into one of the two operations booths to make sure everything is running smoothly. In the meantime, the gears of the stadium are turning, as 4,000—yes, 4,000—credentialed people are opening parking gates, tearing tickets, slinging beers, securing perimeters, unclogging toilets, adjusting the temperature in luxury suites, and directing patrons to their seats. DKR is a monolithic, dense mass of concrete, with thousands of moving parts inside working in concert.

Johnson, the quarterback behind the scenes, walks 8 or 9 miles while this is all happening, and he likely won’t get to enjoy the fruits of his labor until he slumps down on the couch in front of the TV at 2 or 3 a.m. and watches the game on tape. He does, however, make sure that he winds up in the same spot before kickoff. Johnson will position himself at the top of the stadium in the southwest corner. From there, he will track one person trying to make it in before the game begins, picking out someone in something unique—not burnt orange—clocking how long it takes for them to get inside.

Then it’s eight or so more hours until he can breathe a sigh of relief—no one had to be taken to St. David’s, an entire women’s restroom didn’t overflow, all the lights stayed on.

“Truth is,” Johnson says, “I don’t work nearly as hard as these guys on gameday.”

“These guys” are his team, which includes heads of security, parking, building services, special events, and much more. And gameday, as it were, is merely the culmination of a 60-70 hour grind for each. So let’s back up. Gameday is of course technically Saturday, but they like to refer to each home game as game week, and this season, the home opener is followed by two more consecutive ones, including what has the potential to be the most-attended game in DKR history, on Sept. 15 against USC. Game week begins on Tuesday, with a 150-person standing meeting, but actually, let’s back up some more.

Heath Seaton and a power-washer.

Someone has to open the stadium, many parts of which lie dormant from Thanksgiving until mid-summer. Building Services Coordinator Heath Seaton and his team get to work on July 1, giving them two full months to open everything up.

“I walk the stadium, and make sure nothing is broken since it’s been dormant,” Seaton says. “Me and my guys will start power washing July 1. It’ll take until Sept. 1 to get it ready.”

From there, Assistant Athletics Director for Facilities, Events and Operations Brian Womack, BS ’98, starts making assessments with his team. They call plumbers and electricians to make fixes on the upper decks, which haven’t seen human activity in more than half a year. They meet with Environmental Health and Safety to make sure the seats in the stands are safe, and with the fire safety office to check on lingering issues in elevators and on escalators.

“From August on, it’s six days a week,” Womack says. “It’s a sea of people in here.”

This season, Vice President and Director of Athletics Chris Del Conte has made some major changes to the exterior of the stadium, like removing cars from San Jacinto and turning the rechristened Bevo Boulevard into a purely pedestrian, tailgating throughway. That means Bobby Stone, director of Parking and Transportation Services, has his work cut out for him with creating new signage, moving barricades, and otherwise making sure pedestrians are safe with new traffic routes. Safety and Security Manager David Allison, a former 21-year Secret Service Agent, might have to plan differently for the dignitaries to which he is assigned. Jimmy Johnson, assistant vice president for campus safety, will work with the Austin Police Department to ensure that the new carnival-type atmosphere Del Conte envisions is as secure as possible.

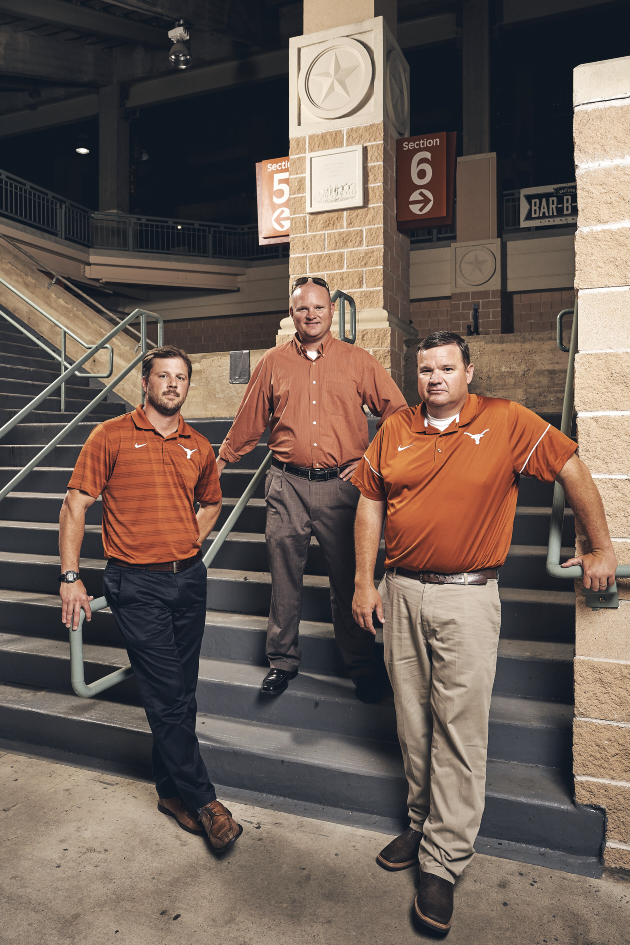

Merrick MyCue, James Barr, and Brian Womack.

Then game week begins, on Tuesday, Sept. 4, with a 150-person meeting that includes every moving piece represented on gameday, from UTPD and St. David’s EMS to cheerleading and the band. Everyone receives their credential and parking passes, and they begin what Jimmy Johnson calls “a dress rehearsal of everything we expect to happen beyond what happens on the field,” including Distinguished Alumnus Award recipients appearing on the field between quarters or Longhorn Hall of Honor recipients standing on the sidelines. The script used to be a thick tome, Arthur Johnson says. Now, Del Conte has streamlined the whole thing. It’s one sheet, front and back.

During the week, necessary adjustments and repairs are made. While Arthur Johnson technically arrives earliest to the stadium on Saturday, he does sleep in his own bed the night before gameday.

“That first game I’m not going home,” says James Barr, assistant athletics director for game operations. “I’ll stay up here and prep.”

So you basically live here all Tulsa weekend? Seaton jumps in. “Yeah, and the next two weekends after that.” For the first time in more than a decade, it’ll be someone else sleeping over inside the stadium, however. Seaton left UT Athletics in August.

The night before the Tulsa game, Parking and Transportation Services begins towing—or as Stone calls it, “relocating,” since technically cars removed from garages and marked parking spots around the stadium are taken to a campus lot rather than a tow lot. At 6 a.m. Stone will brief his staff, and at 7 a.m., the stadium and its surrounding area comes alive. Barr’s team and Stone start opening parking lots. Around 11 a.m. Allison gets in, and the staff and hired workers begin unlocking gates and restrooms, a process that takes two hours. They’ll then do sweeps, rehearse routes for VIPs, and brief with the police. Merrick MyCue, BS ’02, Life Member, assistant athletics director for special events and capital projects, is there around the same time, making sure the suites are good to go. There are canine walks, A/C checks, and inspections on window functionality. Before the Notre Dame game in 2016, a window was out of place, and when it opened, it shattered. During the torrential downpour in 2015 when Kansas State visited, MyCue rushed from suite-to-suite to figure out which ones had leaks.

Jimmy Johnson and David Allison.

During the game, everyone is on call. If there is a safety or security threat, the team uses a system called 247 Software for gameday management.

“There’s a visualization map,” Jimmy Johnson says. “If we have a bunch of emergency medical calls for foodborne illness, and we get 50 dots pop up on the east side, we need to go look at the concessions over on the east side.”

There are two operations booths, and a UTPD officer with access to cameras in fixed locations around the stadium, plus every camera on campus, plus access to drops and feeds from police helicopters, if needed. And, of course, since the clear-bag policy was implemented at campuswide athletics events on Aug. 1, 2017, the eye in the sky can see what you’re carrying with you.

“If we get a call, drunk and belligerent in section 108, they need to take the camera to it,” Womack says. “If the police go, whoever it is, they’re coming out.”

The technology has improved by leaps and bounds in the last few years, too. According to Arthur Johnson, “If somebody comes and taps you on the shoulder, and says, ‘Give me the bottle you have in your right boot,’ you might as well give us that bottle. That means they know. It’s in the right boot. We zoomed in.”

Aside from kicking out hammered fans—which the folks in facilities and UTPD say isn’t particularly a problem at Texas, partially because of the culture and also because bingeing pre-game is likely down since 2015, when alcohol sales inside the stadium went into effect—the control center can also get you in more quickly. They monitor each gate before kickoff to assess the flow of traffic inside. If there’s a bottleneck—which there usually is at Gates 1 and 32—they can radio a staffer near those gates to direct fans to another gate just a couple hundred feet away so they can get in immediately.

After the game, Seaton and his team get to work. Starting at midnight, cleaning crews come in, which Seaton monitors for a few hours before heading home for the night. The entire process takes eight to 10 hours and 150 people, sweeping up peanuts and sorting recyclables and compostables. Starting at noon on Sunday, the power-washing crew comes in, and spends 30-40 hours over the week hosing off spilled beer and sticky patches of Coke and Sno Cone juice, spraying the concourses, the stainless steel, all the doors.

“I tell my guys,” Seaton says, “‘Act like you’re going to sit down in the stadium. Do you want nacho cheese under your seat?’”

If there’s a home game, the team in facilities does the exact same thing all over again. This season, after the Tulsa home opener, the gang has to prepare for USC and TCU in consecutive weeks.

“When you don’t win, the AD gets a few more emails and calls. They could happen during the game—real-time updates. Chris [Del Conte] will get a real big education on Twitter this year.”

Facilities has its work cut out for it. Crickets descend in September and die en masse in elevator shafts. Rains, like the floods during the Kansas State game in 2015, meant 30-40 percent of the support staff couldn’t even get to the stadium. In 2006 against Iowa State, severe lightning storms meant the entire stadium had to shelter in place, a serious concern for safety. Two years ago, a student section bleacher collapsed during the Notre Dame game due to overcrowding—luckily, no one was seriously injured. Two people in the same section often complain that the PA is both too loud and too quiet. There’s always something.

But for all that can go wrong, luckily there hasn’t been a serious incident or game-altering mishap in recent years. There’s only one thing, though, that makes for the perfect gameday experience.

“It’s always better after you win,” Arthur Johnson says. “When you don’t win, the AD gets a few more emails and calls. They could happen during the game—real-time updates. Chris [Del Conte] will get a real big education on Twitter this year.”

When college football began, if you wanted to complain about the team, you had to confront the athletics director face-to-face. What little we know of its early days is relegated to hearsay, hazy remembrances, and apocrypha.

Officially kicking off in 1869 with a 6-4 Rutgers victory over Princeton, the next half-century was largely unregulated, with seasons comprised of as little as just one game, multiple champions being awarded every season by sources of dubious provenance, and games played on rickety, rock-filled fields.

In 1893, Texas formed a football team, going 4-0 against such formidable opponents as Dallas A.C. and San Antonio. It’s unclear whether UT played against the entire city. It’s also unclear exactly where the home games took place, though the Feb. 22 (you read that correctly) contest took place in Austin’s Hyde Park neighborhood.

In 1896, the Texas Longhorns, still in its infancy, began playing games at the Varsity Athletic Field on 24th and Speedway. Later known as the original Clark Field, named after UT proctor “Judge” James B. Clark in 1904, the football team shared the space with track, baseball, and, somehow, men’s basketball. The wooden bleachers filled with up to 20,000 spectators in some instances. With football’s increasing popularity in America, and with Texas performing as somewhat of a powerhouse in the newly formed Southwest Conference, UT Athletics Director L. Theo Bellmont decided that the Longhorn football team needed a new home of its own in 1923.

Bellmont, along with a cadre of student leaders, petitioned the Board of Regents for a concrete stadium, as Texas football had outgrown its current home. In January 1924, the construction project broke ground, with funds raised by students and alumni. Nine months and $275,000 later, Texas played its final game at Clark Field, a 7-7 tie with Florida. Two weeks later—interestingly enough in the middle of the 1924 season—Texas played its first home game at the newly christened, 27,000-capacity War Memorial Stadium, though it wouldn’t be officially dedicated as such until Thanksgiving against Texas A&M.

In front of approximately 13,500 fans, Baylor ruined Texas’ opening day in its shiny new concrete box. On Nov. 24, Texas played A&M in front of 35,000 fans, for whom temporary bleachers had been installed. With the 7-0 victory that day, Texas had both won its first game on that site and played the most-attended home game in school history by a longshot. War Memorial Field was dedicated to the 198,520 Texans who fought and 5,280 who died in World War I.

Two years later, and at a cost of $125,000, the horseshoe was built on the north end, raising capacity to 40,500. In 1948, the stadium expanded again, and officially changed its name from War Memorial Stadium to simply Memorial Stadium. Two L-shaped sections were added to the east and west stands, bringing capacity to 60,130. Shortly after, a young boy named Ted Koy started frequenting the stadium.

“When you played under Coach Royal, no matter what the circumstances were, you did it. We didn’t have a vote. We endured it.”

“I do not remember not going to the stadium for games,” Koy says. “That was before they had lights.” The lights came two days after Koy’s eighth birthday, and Texas played its first night game on Sept. 17, 1955, a 20-14 loss to Texas Tech in front of 47,000 people. By the next expansion, in 1968, when 5,481 seats were added, Koy, BJ ’73, Life Member, was a halfback on a Texas team that employed a three-headed backfield that rushed for more than 2,000 yards. The summer between that season and the beginning of next one, in which Texas would go 11-0 and win the national championship in front of President Nixon, Texas installed AstroTurf, which cut down on maintenance but wasn’t particularly popular with players.

“Especially in those early years of artificial turf, it was basically cement or asphalt with a small pad underneath,” Koy says. “When you hit on it, it was vicious—skin burns, lacerations, broken bones.”

But Koy says the players were resigned to their fate. “When you played under Coach Royal, no matter what the circumstances were, you did it. We didn’t have a vote. We endured it,” he says.

Texas teams endured it for the next 27 years, though the turf was replaced three times in the interim. Ostensibly, the technology advanced in that time span, but the decision to switch back came before the 1996 season. In the intervening years, the upper deck was added, bringing capacity to a whopping 77,809 in 1971; the stadium was re-dedicated to the veterans of all wars and renamed Texas Memorial Stadium and the track encircling the field was reduced from 440 yards to 400 meters in 1977; and in 1986 the Vernon F. Doc Neuhaus-Darrell K Royal Athletic Center was built on the south end of the stadium for $7 million, which served as a locker room, gym, and media center for the team.

Perhaps the person most grateful for the switch back to grass—temporary as it was—wasn’t a player. Coral Noonan-Terry, BS ’98, MA ’99, PhD ’01, Life Member, was a world-champion baton twirler from Southern California when she first saw Memorial Stadium, on a recruiting trip in 1993. Robert Mueller was still Austin’s airport then, and when her plane flew over the stadium, she and her mother assumed it was a professional stadium of some sort—colleges didn’t have stadiums that grand.

She chose UT over Colorado and Florida State, the other schools in her top-three. She still remembers how hard—and how incredibly hot—the field could get.

“It was 20 degrees hotter on that turf,” she says. “If we stood in one spot for too long, our shoes would start melting.” In 1996, UT switched to something called Prescription Athletic Turf, which is natural grass atop a sophisticated drainage system.

Noonan-Terry twirled for eight straight years, earning three degrees along the way, and was on the field for some remarkable Texas milestones: three straight conference titles, Ricky Williams’, BS ’16, 1998 shattering of Tony Dorsett’s NCAA career rushing record against A&M, and the rise of a new star coach, Mack Brown, who arrived on campus in 1998.

But before that could happen, the stadium underwent another series of monumental changes, including its name.

Darrell K Royal, Life Member, coached Texas football for 20 years, transforming a faltering program into a perennial powerhouse, winning three national championships, 11 Southwest Conference titles, and finishing in the top-five of the AP poll nine times. Concurrently, and after stepping away as coach after the 1976 season, Royal was also athletics director until 1980. It’s impossible to concisely state how integral the once-Oklahoman was to the elevation of Texas’ football program. From 1968 until his final season, Texas did not lose at home in 42 straight tries. Thus, in 1996, the decision was made to rename Memorial Stadium once more, for its venerated former coach.

On Sept. 21, 1996, with 83,312 in attendance, the stadium was dedicated as Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. After the season, the athletic center removed Royal’s name, for redundancy’s sake, and renamed Moncrief-Neuhaus, the former being William A. “Tex” Moncrief, BS ’42, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, an oilman, former UT regent, and major donor to the university. The field at DKR was named after Joe Jamail, BA ’50, JD ’53, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, the “King of Torts,” and namesake of both the swimming center and a pavillion at Texas Law, in 1997.

“Burnt orange or Texas orange or whatever it’s called, no one else has that color,” Mack Brown says. “I wanted us to build on being burnt orange. That would be our identity.”

“Coach Royal was so humble that it was hard for him to allow you to brag on him much,” Brown says. “I would ask him about the name [of the stadium], and he would say more about Jamail, his friend. That’s how he was. He deflected all praise.”

Though the stadium was named for his mentor and close friend Royal, Brown made a bright splash around the stadium and its surrounding facilities once he stepped foot on the Forty Acres. He saw white everywhere—why not orange? In short order the stark white was replaced with burnt orange paint, posters, and graphics as far as the eye could see.

“Burnt orange or Texas orange or whatever it’s called, no one else has that color,” Brown says. “I wanted us to build on being burnt orange. That would be our identity.”

Apart from branding geared toward fans—he would later popularize the now-ubiquitous phrase “come early, be loud, stay late, wear orange”—Brown’s strategy was a shrewd recruiting tool, an area he began to excel in as the aughts rolled on. He had three principles in recruiting, which he employed at DKR and Moncrief: smell, sound, and sight.

“I wanted the smell of locker room for the mother to be OK and not be dirty and smell musty,” Brown says. “We needed ‘Texas Fight’ either in the hallways, dressing room, or elevator. And we wanted them taking pictures next to the Ricky statue, next to a picture of Colt; we wanted them to build memories. We wanted the sight to be—that could be me. I may come back as VY or DJ or Colt.”

The stadium capacity fluctuated just before and at the beginning of Brown’s tenure. In 1997, the underside of the stands was renovated—Noonan-Terry remembers bats living under them when she was an undergrad—a visitor’s locker room was added, and a concessions plaza was built. Capacity was reduced to 75,512, but only for a short time. In Brown’s first year, the east side got an upper deck, 52 new suites opened, and a 13,000-square-foot club was added. The following summer, in August 1999, the track was removed and the field was lowered 6 feet to allow the installation of more seats. The stadium was back above 80,000 capacity.

In 2002, Texas installed Bermuda grass, which proved to be arduous to maintain in the scorching Texas sun. The team, the band, and cheerleaders couldn’t practice on the field. By the end of the season, inevitably, the grass was ruined. It lasted only seven years.

In the interim, however, the Longhorns went on a tear. On the Bermuda grass, Brown’s Texas teams—77-13 overall—only lost four games. In 2005, Texas was undefeated and, of course, won the Rose Bowl on Jan. 4 of the following year to claim the BCS National Championship. The following year, the so-called “Godzillatron” LED video scoreboard was installed. For a short time, it was largest of its type in the world. During that era, Texas’ home atmosphere was perhaps unparalleled.

The atmosphere at DKR when Texas is a top team is so electric—bouncy, ecstatically loud, covered in orange—that former Longhorn wide receiver Quan Cosby, BSW ’09, says ESPN College GameDay broadcaster Kirk Herbstreit almost moved to Austin after Texas waxed Missouri during the wide receiver’s senior season. The No. 11 Tigers visited the Longhorns, ranked No. 1 in the country, on Oct. 18, 2008, and with GameDay in town, Longhorn fans showed up in droves to watch the Longhorns win 56-31. Attendance was 98,383, made possible by the addition of 9,000 seats to the stadium the summer before, plus a new memorial plaza, and multi-level seating in the brand new north end zone, named after mega-donor Red McCombs, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus.

“We absolutely beat the crap out of them,” Cosby says. “Our fanbase did not disappoint. Herbstreit said, ‘We got what we expected.’ He and his wife looked at houses.”

The following year saw the stadium expanded and changed to what we know it as today. The south end zone was renovated, and capacity broke the 100,000 mark. Now officially at 100,119, it is the eighth-largest football stadium in the country by capacity, and, for the moment, the second largest in Texas next to A&M’s Kyle Field, after a massive expansion on the Aggies’ part in 2015. FieldTurf was also installed, but technology made leaps and bounds by this point, and the hot asphalt of Koy’s youth was now a cushy pad that more closely mimicked the actual feel of grass.

Since that renovation and expansion, Texas has hired two new head coaches and three athletics directors. After losing the national championship in the 2009 season, Texas has not won 10 games in a season, sniffed a conference title, or played in a prestige bowl game. While dyed-in-the-wool Longhorns still come out on Saturdays, the atmosphere is noticeably tamer, sellouts are rarer, and opposing teams don’t feel the heat that Texas fans brought during Brown’s tenure.

“In our days, there wasn’t a seat in the stadium. Ever. My entire four years,” Cosby says. He has a plan, though, to get DKR packed again. Hear him out.

“If you win, they will come. You hear about fan experience—fan experience is about dubs. You can have George Strait playing [the pregame concert], but if UT doesn’t win, fans aren’t going, ‘Man, we got beat by Iowa State but Strait was awesome!’ I don’t fault the fans. Give ’em something to yell about … they will yell.”

Charged with shaping the future of Texas football culture is Del Conte, hired away from Texas Christian University, a former perennial doormat that has beaten Texas every year since 2013, Mack Brown’s last year as head coach, and with a cumulative score of 153-33 in the last four games. As the saying goes: If you can’t beat ’em, hire ’em.

Del Conte made short order of elevating TCU’s athletics program. He leapfrogged the Horned Frogs from the middling mid-major Mountain West Conference to a dalliance with the dying Big East, into ultimately, a deal with the Big 12. He prioritized what is referred to as non-revenue sports, which solidified programs like baseball, women’s basketball, and the equestrian team. Most notably, however, Del Conte transformed Amon G. Carter Stadium, home of TCU football, with a $164 million fundraising drive that allowed him to resist taking out loans on construction. Del Conte is a smooth talker, a straight shooter with no shame when it comes for asking for cash for improvements.

So when, late this spring, Del Conte, Tom Herman, MEd ’00, Life Member, and other athletics personnel embarked on the This is Texas Tour, a nine-stop whirlwind of pep rallies around the state with the Texas Exes, he made some promises. He’d been walking around the stadium, talking to constituents and staff, and realized a few things were missing. He saw trophies and banners and ephemera tucked away in offices all over athletics facilities, and heard of entire storage facilities in Georgetown that housed memorabilia. Why wouldn’t that all be on display? he wondered. So starting after this season, the North End Zone, named after Red McCombs (and with his blessing), will house the to-be-named Longhorn hall of fame, a tangible museum where kids can look at Ricky Williams’ Heisman trophy and the national championship crystal football before, during, and after games.

“What we do now currently is it’s a cafeteria, a hangout. It doesn’t make sense to me,” Del Conte says. “Wouldn’t it be a great place to walk every student during orientation, to go see Earl Campbell’s trophy, the national championship, the 14 national championships we’ve won in swimming, our gold medalists, everything great that’s happened here in a 30,000-square-foot room, and people can come in and say, ‘Hell yeah, this is Texas.’”

Del Conte is already raising money for the $10 million project, slated to begin in 2019. Beyond the hall of fame, he has signaled a few other changes coming to facilities adjacent to football. One is a major new renovation of a place the fans don’t see, but certainly impacts recruiting: the Moncrief-Neuhaus Athletic Center.

“That’s a building where [our players] are coming to build their craft. It was built for John Mackovic in the late ’90s. It’s past its time,” Del Conte says. “If you asked a chemistry student to work on 1950s Bunsen burners, how are you going to get the best out of that? Our facilities are tired.”

What the fans will see is renovations to the south end zone, also slated to begin construction next year, and to be paid for with $125 million in donor money, and $50 million financed through debt markets and repaid “from premium seating and ticket sales,” according to UT documents obtained by the Austin American-Statesman. It’ll include new clubs, new suites, and a new loge, and will likely reduce capacity.

“The idea isn’t to expand—it’s to provide fans with different options and better options to enjoy the game,” Del Conte says. “We’re fighting the couch.”

Some immediate changes are coming, too. Beginning this season, San Jacinto will be re-christened Bevo Boulevard, a pedestrian-only “fan fiesta” zone, replete with a DJ, three bars, and food trucks in an effort to combine what Austin does best, in Del Conte’s words. The LBJ School lawn will be converted to Longhorn City Limits for a party atmosphere that will include Stubb’s BBQ and a live concert before games. One continuous student section will start at section 29 and wrap all the way around, so that 16,000 screaming youngsters can make the stadium a tense environment for opposing teams. And the extremely unpopular-with-students wristband

policy, implemented in 2017?

“That’s out. Boom. Just have an ID,” Del Conte says. “First come, first served. You want to come in? Let’s be loud, let’s be proud.”

Del Conte is also going to reduce the amount of ads played on the video monitors, in an effort to concentrate on the game instead of products. WiFi has to get better, he says. Concession prices are also going down, too.

Only enough to make a “psychological dent [in people’s wallets],” Del Conte admits. But, he says, “The idea is if you’re charging five bucks for water, how about two or three dollars? A family of four should be able to take their kids, have a great time, and not feel like that was an economic drain. There’s a cost to running the enterprise, however I want them to have a great time.”

Behind-the-scenes, Texas is also quietly working to make DKR a zero-waste facility by 2020 (in-line with the campus plan), an arduous undertaking considering that, for example, more than 80 tons of waste had to be hauled out of the stadium after the Notre Dame game in 2016.

In 2014, Texas hosted the first ever successful zero-waste event on campus, a weekend softball series. In 2017, UFCU-Disch Falk Field became the first Division I stadium to go zero-waste for an entire season, a feat it repeated in 2018.

“So we’re taking what we learned there and translating it to football,” says Lauren Lichterman, BS ’10, Life Member, operations and sustainability coordinator at Texas Athletics. “Football is a beast.”

To achieve this goal, Texas had to look at concessions first, where most of the waste comes from. One huge landfill item was nachos, which used to come in a recyclable plastic boat, with one problem—once cheese was added, the boats were no longer recyclable. Now, nachos come in a compostable paper tray, and even if you don’t finish your gameday snack, the entire thing is compostable, neon cheese and all.

Last season, you may have seen an odd sight out on DeLoss Dodds Way during games, if you happened to be walking by. In the middle of the street, people were sorting recycling and compostables at tables positioned near dumpsters, in an effort to streamline the process. Well, despite not getting any complaints about it—in fact, Lichterman says, passersby remarked that it was a cool process to see—Texas isn’t doing it again this year quite in the same way.

“What we learned is, that is really difficult,” Lichterman says. “We’re coming up with a plan to contain the waste on Saturday and sort it first thing Sunday.”

Lichterman says that she wants surveys going out to fans to include questions about sustainability at DKR to gauge what is important to them.

“I need to pick my next initiative,” she says, “and I want it to be something fans care about.”

When I ask Cosby about what improvements he’d like to see at DKR in the next few seasons, he’s blunt, telling me that better WiFi and cell service, long bemoaned by fans, is actually a detriment because fans will be staring at their phones instead of the action on the field. Since they know they won’t get proper service right now, he posits, they watch the game instead.

Still, Cosby realizes the magic of DKR, that despite having a half-full student section and bare upper decks during certain unsexy matchups the last few years, there’s a specific pull that drags the burnt-orange faithful off the couch and onto hard plastic seats.

“We have people [whose] seats are third generation,” he says. “They’ve had them for 60 years. That’s so cool to think about.”

A woman who has seen it all, who never wavers in her fandom, through national championships and 5-7 seasons, who shows up for San Jose State in 100-degree weather and grits it out against Kansas State in the rain is Nancy Payne, BS ’58, Life Member. While she certainly doesn’t speak for every Texas megafan, she represents a segment of the Longhorn faithful for whom the orange doesn’t run. Payne marched with her high school band to Memorial Stadium as a high schooler in Taylor. She paid the blanket tax as an undergrad in the 1950s, a flat fee that got her into every athletic competition on campus. After college she remembers a game against TCU that was so cold that everyone hid from the sleet under blankets, and she ran to her house across the street at halftime to warm up before heading back. Still, though, DKR is her home, it has been for more than half a century, and nothing is changing about that.

“Probably not,” Payne says, of ever relinquishing her tickets in section three on the 30-yard-line. Before every season, she hesitates about purchasing season tickets. “A good friend laughed once and said, ‘Nancy, I believe you will die in that stadium.’”

Zero-waste. State-of-the-art clubs. Cabana-meetup-areas (Del Conte says this might be a thing). These are more than just buzzwords; they’re important to the continued success of the Texas Longhorns football team in that the stadium that they (and, to a large extent, their fans) call home is a living, breathing organism. There’s the cliche about a city or building being a character in a film, but if one were to make a movie about Texas football, the stadium would be one of the stars.

Cosby has a point, though, when he tells me that wins are really, truly what matters in the gameday experience, and, in a cruel twist, the only part of the equation that the 4,000 contractors on gameday, the facilities staffers sleeping in first aid rooms all weekend, not even Chris Del Conte himself can control.

What is special about the stadium isn’t a local craft IPA or a local country musician singing about how he won’t drink a craft IPA or any of the other ephemera swept away on Sunday morning and locked up after Thanksgiving. It’s also not about the structure itself. After all, what’s a hunk of concrete and stainless steel without the crowd inside, a mass that would make up the entire population of Aruba, euphorically going hoarse in sync during a moment they will relay to their children and grandchildren?

It’s intangible, it’s a moment. The building will crumble someday, but what happened inside will live forever.

Photos: UT Athletics; Matt Wright-Steel (4).

4 Comments